No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

page 241 note 1 It may mean ‘of many verses,’ but how do we explain ![]() 101 ? NO. CXXXIII. VOL. XV.

101 ? NO. CXXXIII. VOL. XV.

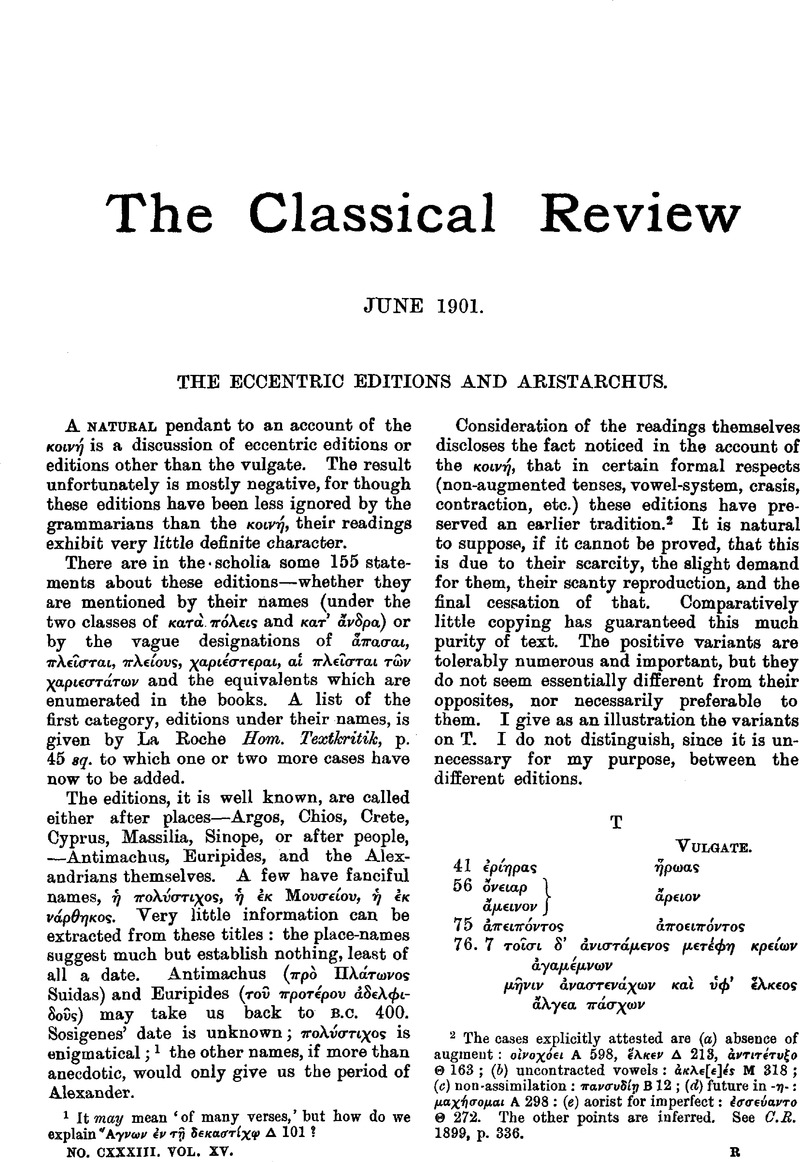

page 241 note 2 The cases explicitly attested are (a) absence of augment: οἰνοχει A 598, ἕλκεν Δ 213, ντιττυξο Θ 163; (b) uncontracted vowels: ἀκλε[ε]ς M 318; (c) non-assimilation: πανσυδη B 12; (d) future in -η-: μαχσομαι A 298: (e) aorist for imperfect: σσεαντο 272. The other points are inferred. See C.B. 1899, p. 336.

page 242 note 1 With this is connected the similar question, were Zenodotus' dialectal changes ![]() arbitrary or based on evidence? Cauer, l.c. p. 22 holds that they were arbitrary, Fick, Ilias, p. 79 and Leaf, Iliad, ed. 2 Θ 470 al. that they were ‘hardly invented by Zen.’ ἰλιδης, ἰλος have now the unexpected support of a vase, Walters, H. B., J.H.S. 1898, p. 286.Google Scholar

arbitrary or based on evidence? Cauer, l.c. p. 22 holds that they were arbitrary, Fick, Ilias, p. 79 and Leaf, Iliad, ed. 2 Θ 470 al. that they were ‘hardly invented by Zen.’ ἰλιδης, ἰλος have now the unexpected support of a vase, Walters, H. B., J.H.S. 1898, p. 286.Google Scholar

page 243 note 1 Though it is not to my purpose to magnify the position of Ar. as a critic, I am unable to find the careful discussion of passages in Cauer, Grundfragen d. Homerkritik, pp. 20–35—a discussion with the object of establishing that in some passages Aristarchus did introduce his own bare conjectures into his text—convincing, and I doubt if argumentation on particular scholia—all more or less imperfect—is likely to lead to any substantive result. The method must be general, not particular. In especial I must deny Cauer's generalisation, p. 29, that in matters of orthography, &c., Aristarchus went against tradition. He went against the vulgate certainly, but that his reforms were based on the authority of the eccentric editions is either explicitly stated or may be fairly inferred.

The humour spent by Römer and others over the scholion I 222 (Cauer, p. 25) is misplaced. The scholion simply states that Aristarchus disapproved of the lection of the κοιν, but did not alter it because he found it ν πολλαῖς. There is no ‘pedantry’ here: it is implied that if the eccentric editions had been unanimous against the κοιν, Aristarchus would after his usual fashion have put their reading into it.

Again it is perhaps worth while pointing out that Cauer's argument (p. 31) that περονα (A 350) cannot have been found by Ar. in the majority of his MSS., or else it would not have vanished from our MSS., is groundless, οἰνοχει A 458 was in the Argive, the Massaliote, and Antimachus' edition, and Ar. read it: it is not in a single actual MS. χαιν A 91 was in the editions of Sosigenes, Aristophanes, and Zenodotus. ![]() was in the Massaliote and in the ed. of Khianus. Aristarchus approved both these II.: but neither they nor the similarly attested variants πον 124, βουλν 258, μαχσομαι 298, προρεσσαν 435, &c., have left any trace in our MSS.

was in the Massaliote and in the ed. of Khianus. Aristarchus approved both these II.: but neither they nor the similarly attested variants πον 124, βουλν 258, μαχσομαι 298, προρεσσαν 435, &c., have left any trace in our MSS.

page 243 note 2 For then it would be necessary to weigh them against the expressions in the opposite sense, which testify to a wide-spread belief in the arbitrariness of Ar.'s method. Plutarch and Athenaeus are antiquarians, Alexander δ Κοτιαες a rhetor, and all three comparatively late, and perhaps their language is inexact; but it is undeniably singular that we find Aristarchus' successor Ammonius, his disciple Dionysius Thrax—scholars older than Didymus, and as likely prima facie as he to be well informed— characterising their master's critical procedure in unequivocal terms.

In the case of the post-Christian and non-philological writers I suggest that the loss, or partial loss of the eccentric editions, may have given Aristarchus' agreements with them the air of independent conjectures: but this cannot be the case with members of his school.

page 243 note 3 I add the figures: of Aristarchus' 664 known readings 6 are in Class I., 45 in II., 49 in III., 564 in IV.; of the latter 25 belong also to III.

page 244 note 1 It is needful here to distinguish between verbal variants and atheteses or omissions. All that is said in this article refers to the former class only. In athetising it is plain Aristarchus was guided by internal considerations solely: but the method was harmless just because it resulted in nothing worse than θτησις viz. an obelus on the margin of a copy.

The distinction made by Ludwich, A.H.T. ii. 135, between Ar.'s atheteses and his omissions ![]() viz. that he athetised on internal grounds and where the line was omitted in no edition, but omitted

viz. that he athetised on internal grounds and where the line was omitted in no edition, but omitted ![]() where the line was omitted in one or more copies, sounds extremely reasonable, and may be true: but it needs to be said that there is no actual evidence for it. I give the details for the Iliad—

where the line was omitted in one or more copies, sounds extremely reasonable, and may be true: but it needs to be said that there is no actual evidence for it. I give the details for the Iliad—

Σ 39 ath. Ar. Zen. om. Argiva.

Φ 290 ath. Ar. Seleucus. om. Cretensis (if κ[ρητικ is right in Ammonius).

Two atheteses (out of 366) therefore have ancient support, none of the omissions (E 808, II 613, Φ 73) have.

It is convenient to give here briefly the results upon the converse question, the effect of atheteses and omissions upon the subsequent text.

Atheteses of Aristarchus coinciding with omission in the later text:

1 B 558 παραιτητον Ar. om. b, g, h Ven. A Pap. Bodl. Gr. class α 1 (P).

2 H 353 ath. Ar. om. ut vid. Dio Prus. LV. 15.

3 I 44 ath. Ar. om. T.

4 I 694 ath. Ar. 694, 5 om. Vat. 16.

5 Ψ 810 ath. Ar. om. Vat. 14.

6 Ω 556 ath. Ar. 556 and 7 om. Vat. 1, 23. Omissions:

E 808 om. Ar. om. L 9, Vat. 16.

The effect in both cases is negligible.