No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

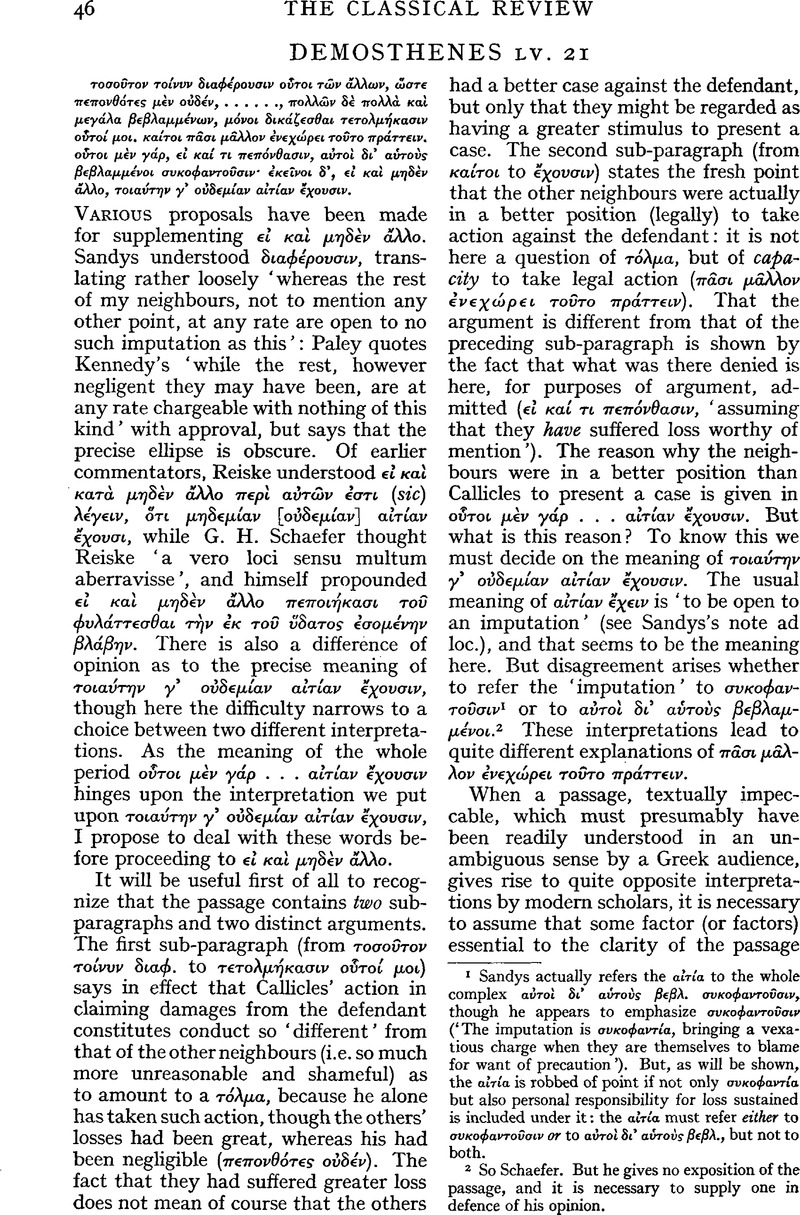

page 46 note 1 Sandys actually refers the αὐτ⋯α to the whole complex αὐτο⋯ δι' αὑτοὺς βεβλ συκοφαντο⋯σιν, though he appears to emphasize συκοφαντο⋯σιν (‘The imputation is συκοφαντ⋯α, bringing a vexatious charge when they are themselves to blame for want of precaution’). But, as will be shown, the αἰτ⋯α is robbed of point if not only συκοφαντ⋯α. but also personal responsibility for loss sustained is included under it: the α⋯τ⋯α must refer either to συκοφαντο⋯σιν or αὐτο⋯ δι' αὑτοὺς βεβλ., but not to both.

page 46 note 2 So Schaefer. But he gives no exposition of the passage, and it is necessary to supply one in defence of his opinion.

page 48 note 1 Cf. §I οὕτω διατ⋯θηκ⋯ με συκοφαντ⋯ν, ὥστε πρ⋯τον μ⋯ν τ⋯ν ⋯νεψι⋯ν τ⋯ν ⋯αυτο⋯ κατεσκε⋯αςεν ⋯μφισβητεῖν μοι τ⋯ν χωρ⋯ων κτλ.

page 48 note 2 This is why the αἰ⋯τα, if it is to have point, must be referred to συκοφαντο⋯σιν alone: it is the general συκοφαντ⋯α of Callicles that makes it hard for him (so the defendant would have us believe) to present a case; it is the lack of any presumption (from previous actions notnecessarily involving negligence) of συκοφαντ⋯α that places the others in a better position to present a case.

page 49 note 1 To the forward-looking character of the idiom the Aeschines passage is only an apparent exception, because the emphatic element is anticipated by ⋯κεῖν⋯ γε. Also forward-looking is the εἰ μ⋯ δι⋯ type of ellipse (e.g. Plat. Gorgias, 516e εἰ μ⋯ δι⋯ τ⋯ν πρ⋯τανιν, ἐν⋯πεσεν ἄν cf. Goodwin, M.T., § 476, 3). In general, forward-looking subordinate clauses and constructions in Greek deserve further study particularly where, to the reader, their nature tends to be obscured by preceding matter in the same sentence. Interesting examples are Herod. i. 60 … μηχαν⋯νται … πρ⋯γμα εὐηθ⋯στατον … μακρῷ, ⋯πε⋯ γε ⋯πεκρ⋯θη ⋯κ παλαιτ⋯ρου το⋯ βαρβ⋯ρου ἔπε⋯ γε ⋯θνος τ⋯ Ἑλληνικ⋯ν …, εἰ κα⋯ τ⋯τε γε κτλ. Antiph. ii. 10 ⋯πολ⋯εσθαι δ⋯ ὑφ' ὑμ⋯ν, εἰ κα⋯ εἰ κ⋯τως μ⋯ν ⋯ντως δ⋯ μ⋯ ⋯π⋯κτεινα τ⋯ν ἄνδρα, πολὺ μ⋯λλον δ⋯και⋯ς εἰμι. In the first case, the ⋯πε⋯ γε clause looks forward to τότε υε in the second, the εκα⋯ clause to πολὺ μ⋯λλον, but neither fact is immediately grasped by the reader. On the other hand, both passages properly spoken would offer no difficulty to a Greek. Similarly in Herod, ii. 101 τ⋯ν δ⋯ ἂλλων βασιλ⋯ων, οὐ γ⋯ρ ἒλεγον οὐδεμ⋯αν ἒργων ⋯π⋯δεξιν, κατ' οὐδ⋯ν εἶναι λαμπ⋯τητος, πλ⋯ν ⋯ν⋯ς το⋯ ⋯σχ⋯του αὐτ⋯ν Μο⋯ριος,, I believe that τ⋯ν ἂλλων βασιλ⋯ων πλ⋯ν ⋯ν⋯ς 〈=οὐδ⋯να πλ⋯ν ⋯ν⋯ς, with which it goes partitively, and that it is unnecessary to assume an anacoluthon, or understand ouSeVo from οὐδ⋯να from κατ' οὐδ⋯ν εῖναι λαμπρ⋯τητος Tor (as How and Wells explain the construction).

page 49 note 2 We might, in Dem. viii. 62 and Lucian, if we considered those passages only individually, understand ὑβρ⋯ξει and ὠφ⋯ληνται respectively from what has gone before. But this method of interpretation would not suit the other passages. Nor is ὠφ⋯ληνται an accurate supplement for Lucian's ellipse. Lucian's point is that the benefit from philosophy is shown by an improvement in behaviour. True, ὑβρ⋯ζει and ὠφ⋯ληνται Prepare us for the meaning of the respective apodoses: that does not alter the fact that it is from those apodoses themselves and the thought underlying them that the ellipse is to be supplemented.

page 49 note 3 Riddell (Digest, § 20) offers what seems an entirely misconceived explanation of the TI instances in Plato. Comparing usages such as Apol. 20 d ὃνα τ⋯ τα ⋯τα λ⋯γεις (‘ τ⋯ in itself is the full representative complement of the sentence’), he says of our instances: ‘The sentence is complete; the τι and the τι 礸λλο stand for full propositions.’ The usages he compares are really quite different from ours. In ὃνα τ⋯ τα ⋯τα λ⋯γεις (‘ τ⋯ stands for a full proposition, because there is nothingto define τι except the full proposition which the question assumes will follow; in our instances, on the other hand, τι 礸λλο is defined by its complement in the apodosis: if that complement is a substantive, τι 礸λλο will be a substantive also, and it is necessary to supply a verb inthe ellipse with which τι 礸λλο can enter into grammatical relationship. This is made quite clear by Symp. 222 d τιigr 礸λλο is defined by its complement ⋯ν μ⋯σῳ ἠμ⋯ν Ἀγ⋯θωνα κατα κεῖσθαι, itself a virtual substantive and the object of ἔα;; a part of edv is to be supplied in the ellipse to govern τι 礸λλο had the clause been completed, it would have been ⋯⋯ν μ⋯ τι ἄλλο ⋯⋯σῃς), by the passages from the orators, and by Soph. frag. 23, where Person rightly remarks that 礸λλο pismust be in the same case as κάπα i.e. μηδ⋯ν 礸λλο is a substantive. As the preponderance of evidence seems to be in favour of μηδ⋯ν礸λλο and τι 礸λλο being used as substantives, and not adverbially, I have thought it best to treat them as substantives throughout. But in Lucian, loc. cit. μηδ⋯ν 礸λλο might be adverbial (sc. εμηδ⋯ν ἄλλο βελιους δι⋯γουσι.).

page 50 note 1 Here a part of the apodosis precedes the elliptical phrase, but the part which is emphatic υis-⋯-υis εἰ μ⋯τι follows it.

page 50 note 2 εὀ in the historic sequence, is here grammatical. But it may be doubted whether we should have had ἐάν, even had the sequence been primary.

page 50 note 3 Whereas in the μηδ⋯ν instances ⋯⋯ν is used when grammatically necessary, Soph. loc. cit., Xen. Anab. vii. 8. 3; cf. Dem. xxiii. 156 λογισμ⋯ν λαβών, ⋯τι ληφθ⋯σεται, κἄν μηδεν⋯ τ⋯ν ἄλλων, τῷ γελιμῷ,

page 50 note 4 For similar crystallized phrases cf. the use of εἰ δ⋯ μ⋯ ‘otherwise’ (Goodwin, M.T., §478) and of 礸κν. in Plat. Meno, 72 c, Rep. 477 a and 579 d (Thompson, Syntax of Att. Gk. 189.3 (c), (2)). By a coincidence, Ps.-Longinus has this use of 礸κν in an ellipse similar to those we are considering, Περ⋯ ῞ϒΨους 33.4 οὐδ⋯ν ἥττον οἶμαι τ⋯ς με⋯ζονας αἰτ⋯ας … τ⋯ν το⋯ πρωτε⋯ου Ψ⋯φον μ⋯λλον ⋯ε⋯ φ⋯ρεσθααι, κἂν εἰ μηδεν⋯ς ⋯τ⋯ρου, τ⋯ς μεγαλοφροσ⋯νης αὐτ⋯ς ἔνεκα.

page 51 note 1 Reiske, I believe alone of the editors, was led aright by his instinct to seek the supplement in the apodosis. But his version will not do, because it hints that the defendant had some reason for complaint against the other neighbours, and not merely against Callicles. Such an assumption is nowhere implied in the speech, and its introduction here is either irrelevant to the argument that the other neighbours had a better case than Callicles, or tends to contradict it, by drawing attention to material upon which the defendant might draw for a defence against them.