No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

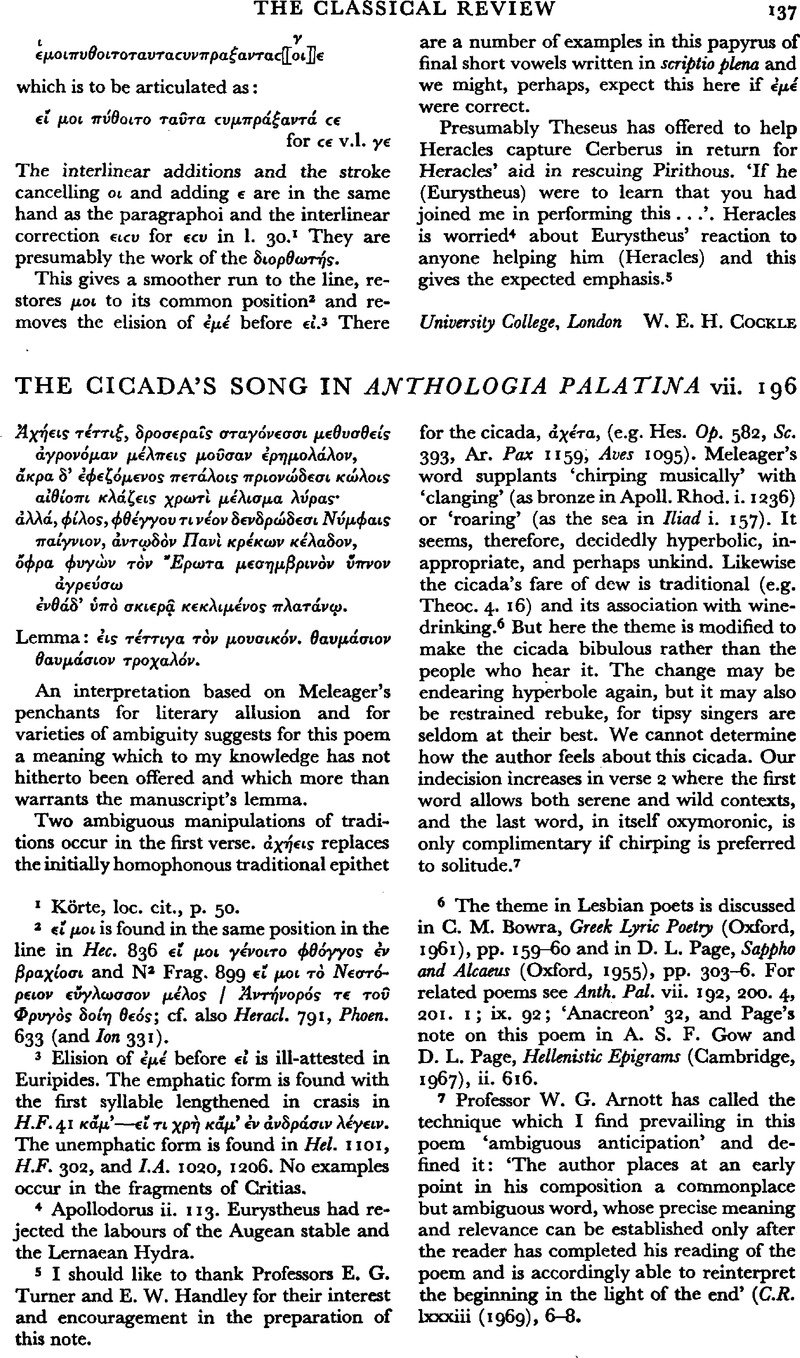

page 137 note 6 The theme in Lesbian poets is discussed in Bowra, C. M., Greek Lyric Poetry (Oxford, 1961), pp. 159–160Google Scholar and in Page, D. L., Sappho and Alcaeus (Oxford, 1955), pp. 303–306Google Scholar. For related poems see Anth. Pal. vii. 192, 200. 4, 201. 1; ix. 92; ‘Anacreon’ 32, and Page's note on this poem in A. S. F. Gow and D. L. Page, Hellenistic Epigrams (Cambridge, 1967), ii. 616.

page 137 note 7 Professor W. G. Arnott has called the technique which I find prevailing in this poem ‘ambiguous anticipation’ and defined it: ‘The author places at an early point in his composition a commonplace but ambiguous word, whose precise meaning and relevance can be established only after the reader has completed his reading of the poem and is accordingly able to reinterpret the beginning in the light of the end’ (C.R. lxxxiii (1969), 6–8.

page 138 note 1 e.g. Gow, A. S. F., Theocritus (Cambridge, 1952), iiGoogle Scholar. III–12, ‘almost universally admired’, and Douglas, N., Birds and Beasts of the Greek Anthology (London, 1929), p. 194Google Scholar, ‘in fact, so many polite things are said that it is quite a relief to find Meleager begging the cicada to ‘sing a new song’ by way of a change’.

page 138 note 2 See Lawton, W. C., The Soul of the Anthology (Oxford, 1923), pp. 79 and 143Google Scholar. Perhaps in Theoc. Ep. 5 the time is not midday and therefore Pan may be awakened with impunity. A. LaPenna, ‘Marginalia et Hariolationes Philologae’, Maia v (1952), 93–112, argues that Meleager has in mind the setting of Plato's Phaedrus. The noontime (259 a), the plane tree (229 a), the nymphs (230 b), the desire to sprawl out (229 b) and to sleep (259), and the role of the cicada (230 c) make up a series of noteworthy coincidences. But as LaPenna remarks, all this imagery was conventional in the Hellenistic era. Furthermore there are disparities. Meleager does not retain Plato's breezes, stream, and grass associated with the cicada (229 a and 230 c). The dewdrinking cicada is too common to be attributed to any particular or single source; the inebriation appears to be original. Plato's cicadas deliberately prevent men from noon-time sleep (259 b), and Meleager neither adopts nor revises this critical factor; he ignores it. Therefore he is not ‘using’ Plato in the same sense that he is using Moschus, Theocritus and Hesiod. Secondly the cicada as musician is fundamental to our poem but absent in the Phaedrus. Finally, there is no correlation between the character and function of Eros in the two works. In the earlier work, in fact, the insect may be prophet of the Muses (R. Böhme, ‘Unsterbliche Grillen’, J.D.A.I. 69 [1954], 49–66).

page 138 note 3 Gow, A. S. F., Theocritus. (Cambridge, 1952), ii. 111–112, regarding Theoc. 7. 138–9:Google Scholar

το⋯ δ⋯ ποτ⋯ σκιαραῖς ⋯ροδαμν⋯σιν αἰθαλ⋯ωνεςτ⋯ττιγες λαλαγε⋯ντες ἔχον π⋯νον…

The ‘facts’ explaining this passage are reported at length in the scholia quoted by F. Dubner, Scholia in Theocritum (Scriptorum Graecorum Bibliotheca, Paris, 1849), p. 60:

σκι⋯ν ποιο⋯σαις…Αἰθαλ⋯ωνες, οἱ τ⋯ττιγες, παρ⋯ τ⋯ αἴθεσθαι ὑπ⋯ κα⋯ματος. ὅταν γ⋯ρ ⋯στιν⋯τος κα⋯ κα⋯μα, α⋯λλον φθ⋯γγονται.… οἱ δ⋯τ⋯ττιγες, οἱ αἰθαλ⋯ωνες, ἤγουν οἱ τῇ θ⋯ρμῃ το⋯ ⋯λ⋯ου χα⋯ροτες, π⋯νον εἱχον, ἤγουν ⋯π⋯νουνἄδοντες ⋯π⋯ τοῖς κλ⋯δοις τοῖς ςκιερῖς, δασ⋯σι, τοῖς σκι⋯ν ⋯μποιο⋯σιῇ τἱ συνεχε⋯ᾳ τ⋯ν φ⋯λλν. …αἰθαλ⋯ωνες, οἱ ὑπ⋯ το⋯ ⋯λ⋯ου αἰθ⋯μενοι ὅθενκα⋯ ᾠδικώτεροι γ⋯νονται.