No CrossRef data available.

page 150 note 1 So at Ovid, Met. XV. 9, cod. Mus. Brit.

Kings 26 (saec. xi.), has ‘ gre ’ (sic) for Graeca, an example which chance thrusts upon me. There are, as everybody knows, scores of others in MSS. of all periods.

page 150 note 2 ‘ Hacmen ’ scribebat siquando debuit ‘ Acmen ’ scribere et ‘Harpocratem’ rusticus ‘Arpocratem’ (cf. ad CII. 4).

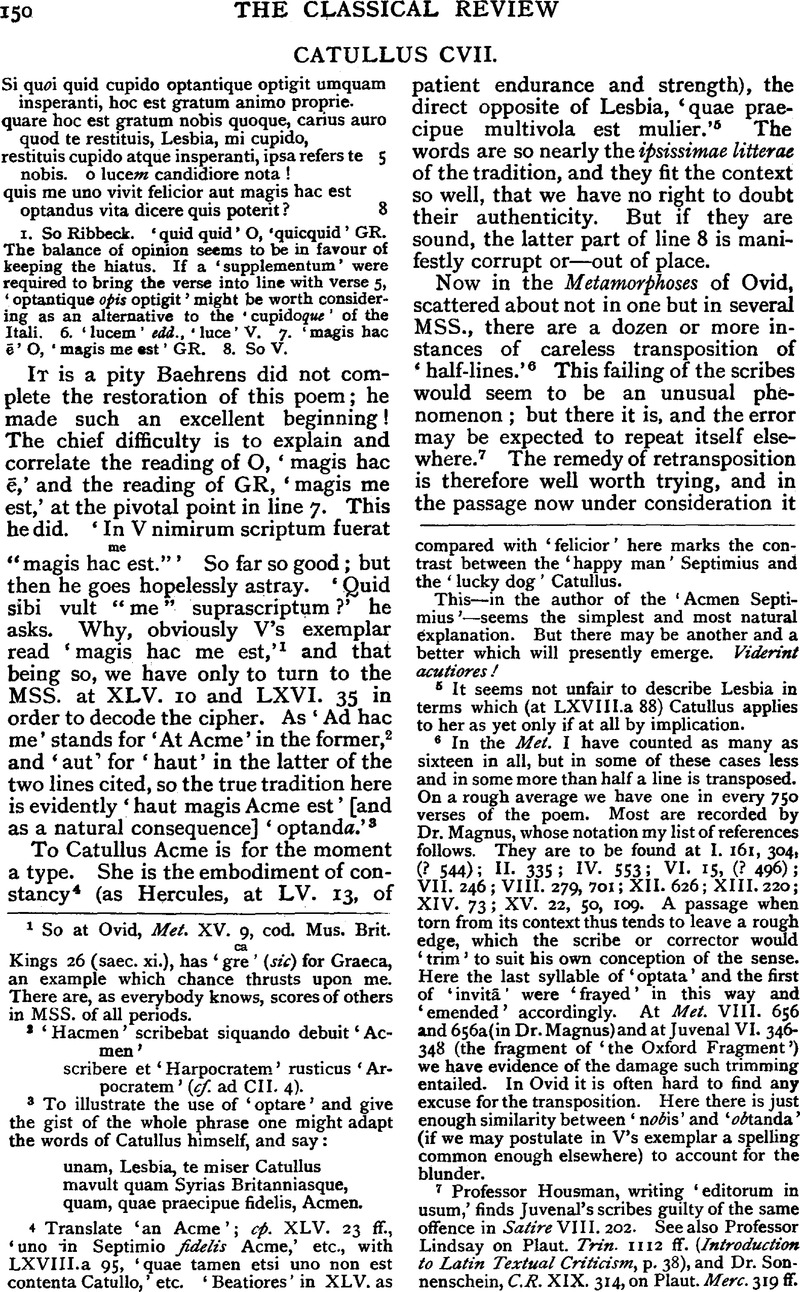

page 150 note 3 To illustrate the use of ‘optare’ and give the gist of the whole phrase one might adapt the words of Catullus himself, and say:

unam, Lesbia, te miser Catullus

mavult quam Syrias Britanniasque,

quam, quae praecipue fidelis, Acmen.

page 150 note 4 Translate ‘an Acme’; cp. XLV. 23 ff., uno in Septimio fidelis Acme,' etc., with LXVIII.a 95, ‘quae tamen etsi uno non est contenta Catullo,’ etc. ‘Beatiores’ in XLV. as compared with ‘felicior’ here marks the contrast between the ‘happy man’ Septitnius and the ‘lucky dog‘ Catullus.

This—in the author of the ‘Acmen Septimius’—seems the simplest and most natural explanation. But there may be another and a better which will presently emerge. Viderint acutiores!

page 150 note 5 It seems not unfair to describe Lesbia in terms which (at LXVIII.a 88) Catullus applies to her as yet only if at all by implication.

page 150 note 6 In the Met. I have counted as many as sixteen in all, but in some of these cases less and in some more than half a line is transposed. On a rough average we have one in every 750 verses of the poem. Most are recorded by Dr. Magnus, whose notation my list of references follows. They are to be found at I. 161, 304, (? 544); II. 335; IV. 553; VI. is, (? 496); VII. 246; VIII. 279, 701; XII. 626; XIII. 220; XIV. 73; XV. 22, 50, 109. A passage when torn from its context thus tends to leave a rough edge, which the scribe or corrector would ’trim’ to suit his own conception of the sense. Here the last syllable of ’optata’ and the first of ‘invitᾱ.’ were ‘frayed’ in this way and ‘emended’ accordingly. At Met. VIII. 656 and 656a(in Dr. Magnus) and at Juvenal VI. 346–348 (the fragment of ‘the Oxford Fragment’) we have evidence of the damage such trimming entailed. In Ovid it is often hard to find any excuse for the transposition. Here there is just enough similarity between ‘noiis’ and ‘obtanda’ (if we may postulate in V's exemplar a spelling common enough elsewhere) to account for the blunder.

page 150 note 7 Professor Housman, writing ‘editorum in usum,’ finds Juvenal's scribes guilty of the same offence in Satire Vlll. 202. See also Professor Lindsay on Plaut. Trin. 1112 ff. (Introduction to Latin Textual Criticism, p. 38), and Dr. Sonnenschein, C.R. XIX. 314, on Plaut. Merc. 319 ff.

page 151 note 1 ‘Vox ponderis plena “ipsa” valet “ tua sponte,” ut LXIII. 56, LXIV. 81, Aen. Vl. 146.’ Baehrens ad loc.

page 151 note 2 Cf. ’Cheerful and tearful,

with quick, busy brain,

swayed hither and thither

in fluttering pain;

cast down unto death,

soaring gaily above;

oh, happy alone is the heart that can love’

(W. Holt Hutton, from the German).

page 151 note 3 CVII., ‘“invitam” dicere quis poterit ?

page 151 note 4 VIII. 12 ff.: … iam Catullus obdurat nee te requiret nee rogabit invitam.

Cf. also ‘miser vive‘ with ‘vivit felicior’ and ‘candidi soles’ with ‘o lucem candidiore nota.’

page 151 note 5 Cf. the last lines of XXVI.:

o ventum horribilem atque pestilentem! and XLIII.:

tecum Lesbia nostra comparator ? …

o saeclum insipiens et infacetum!