Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 February 2009

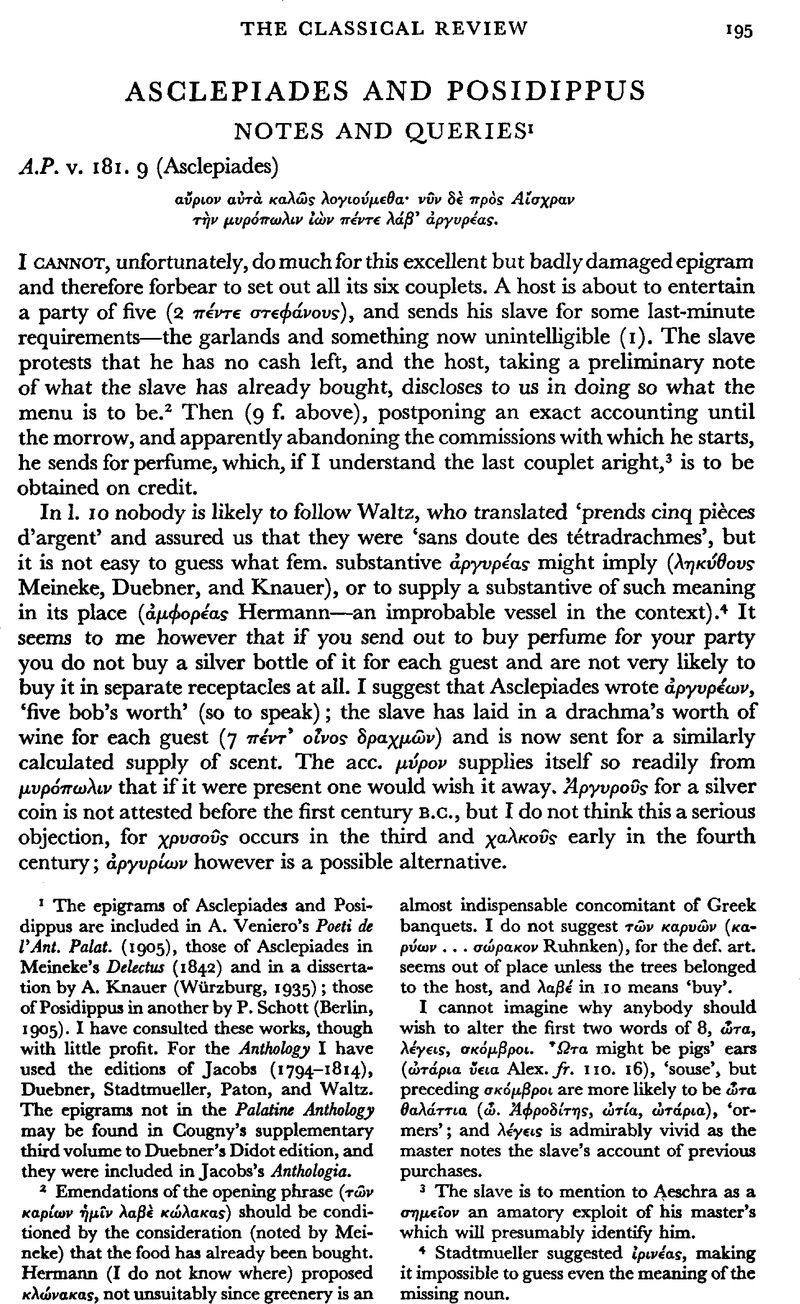

page 195 note 2 Emendations of the opening phrase (![]() should be conditioned by the consideration (noted by Meineke) that the food has already been bought. Hermann (I do not know where) proposed κλώνακας not unsuitably since greenery is an almost indispensable concomitant of Greek banquets. I do not suggest (

should be conditioned by the consideration (noted by Meineke) that the food has already been bought. Hermann (I do not know where) proposed κλώνακας not unsuitably since greenery is an almost indispensable concomitant of Greek banquets. I do not suggest (![]() Ruhnken), for the def. art. seems out of place unless the trees belonged to the host, and λαβέ in 10 means ‘buy’.

Ruhnken), for the def. art. seems out of place unless the trees belonged to the host, and λαβέ in 10 means ‘buy’.

I cannot imagine why anybody should wish to alter the first two words of 8, γα, λῶέγεις, σκόμβροι. ‘Ωγα might be pigs’ ears (ώγέρια εια Alex. fr. 110. 16), ‘souse’, but preceding σκόμβροι are more likely to be ![]() , ‘or mers’; and λέγεις is admirably vivid as the master notes the slave's account of previous purchases.

, ‘or mers’; and λέγεις is admirably vivid as the master notes the slave's account of previous purchases.

page 195 note 3 The slave is to mention to Aeschra as a σημεὶον an amatory exploit of his master's which will presumably identify him.

page 195 note 4 Stadtmueller suggested ίρινέας making it impossible to guess even the meaning of the missing noun.

page 196 note 1 According to Stadtmuellcr ει is due to the corrector, but I do not know why W. should prefer -ῃ.

page 196 note 2 Housman collected examples in J. Phil. xvi. 261, xx. 40.

page 197 note 1 For instance the temple of Artemis Leu-cophryene at Magnesia had stone screens dedicabetween the columns and the antae, and a marble doorway between the columns (Robertson, Gr. and Rom. Arch., 157 and fig. 68).

page 197 note 2 According to Waltz Hecker showed con-clusively that the temple in question was that of Arsinoe-Aphrodite on Zephyrium (the subject of epigrams by Posidippus, Hedylus, and Callimachus); and he added his own conclusion that it was decorated with horses in sculpture. Hecker's observations will be found fellowin his Comm. Crit. ii. 71, but I devote no more than a footnote to these fancies, for to sup-pose that such epigrams commemorate real dedications or refer to any particular temple is to misconceive their character. If v. 202 is by Posidippus, I should guess his puzzling adj. εύππων to be due to Lysidice's dedication of a spur in the epigram he is copying, It is relevant that ἵππος and πῶλος have equivocal meanings in such contexts and that the two nouns bear them in this pair of epigrams.

page 197 note 3 I should not myself go to the stake for the ascription, and it may be worth remembering that the elegy on old age first published by Diels in Sitz. Berl. Ak. 1898, 845 (Page, Gk. Lit. Pap. i. 470) is ascribed by some to a younger namesake and fellowin townsman of the epigrammatist. If they are right, he might compete for the authorship of these undistinguished lines. Cf. also P. Lit. Lond. 60.

page 198 note 1 ‘Ηγέω … II trans, labour at, ό λιθουργόός … ἐμόγησε κόρας’ say L. and S., howling dismally—and the more discreditably since the entry was not taken over blindly from ed. 8.

page 198 note 2 The δράκοντες in whom they are found have bushy (βοστρυχώδης) golden beards, like the πώγων χολοὦβαφος of the δράκων in Nic. Th. 443; and so here (2). This is a puzzle, which I cannot solve. No snake has anything resembling a beard, but πώγων need not imply hair, and many have yellow lower surfaces, of which a part would be visible below the jaw if the snake raised its head. Mr. H.W. Parker of the British Museum kindly tells me also of a colour variety of Coluber jugularis (a species of aggressive demeanour and common in the Near East) which is melanotic above and below except for chin and throat, which are yellow variegated with red. Such an explanation however, though it would explain the colour of the πώγων, would conflict with Philumenus (30. 2), who equips his δράκων with ἀπόφυσίς τ ις below the chin; and earlier Greek art at any rate snakes with goat- like beards pendent from the jaw are common. Those on Laconian stelae (e.g. Berlin Gr. Skulpt. ii. 1. pi. 22), on the Corfu Gorgon pediment (Rodenwaldt Korkyra ii. pll. 3–7), the snake with a visibly hairy beard which swallows Jason on the Douris cup (Pfuhl Mai. u. Zeichn. fig. 467), and some others, might perhaps be regarded as super natural. Not so however those carried by beards, Maenads (Pfuhl, fig. 379), or that in island of Nisyros, which, with its fauna, Poseidon heaves at a giant (Millingen, Anc. Uned. Mon., pi. 7)—references which I owe to the kindness of Sir John Beazley. Mr. Parker suggests that such beards may be defaces, rived from lizards, for a number of these have on the throat spiny scales of some length which may look beard-like when the throat a is inflated—a common habit in the widely distributed Agamidae family. Perhaps they inspired also the beards and Newgate fringes sported by some of the snakes in Botticelli's drawings for Cantos 24 and 25 of the Inferno, though these are no doubt intended to be monstrous.

Philostratus' description of the stone suggests an opal, and it is probably irrelevant that he is writing of India where opals apparently do not occur.

page 198 note 3 He gave no reference and I have failed to discover what else Diels said.

page 199 note 1 Usener's desire (Rh. Mus. xxiv. 342) to write albo is intelligible.

page 199 note 2 Cf. Plin. N.H. vii. 85. 3 This troublesome epigram was discussed by H. W. Prescott in Class. Phil. v. 494—profitably, though I cannot accept all his conclusions.

page 199 note 4 A. J. Phil. xxi. 59.

page 199 note 5 Ib. 54.

page 199 note 6 According to Schol. Aeschin. 2. 151 Cyrebion was Aeschines' brother-in-law and his real name was Epicrates.

page 199 note 7 Both names are attested elsewhere, but Corydus (‘Lark’) is known to have been the nickname of a man named Eucrates (Ath. vi. 241 D), and Phyromachus, as Prescott noted, is likely also to be a nickname (ό φὺρδννμαχόμενος, ‘Hooligan’ or ‘Rough’), earned by his prowess in the brawls in which parasites constantly engaged and to which άγώνων (7) no doubt refers. Athenaeus records from Comedy several more references to Corydus not here relevant.

page 200 note 1 I.G. ix2. 1. 17. Klaffenberg there corrects a dating c. 280 proposed by Weinreich, who had published the entry relating to Posidippus in Herm. liii. 434.

page 200 note 2 To this decade presumably belong a lost epigram on a gluttonous female trumpeter who appeared in Ptol. Philadelphus' procession (Ath. x. 415 A), and, if it is his, a distich on Aphrodite-Berenice (A. Plan. 68). A.P. v. 134, which mentions Zeno and Cleanthes together, might have been written after Zeno's death in 262 B.C. and is not likely to have been written many years before.

page 200 note 3 He supposed Phyromachus to have fallen into a trench owing to his damaged eyes (6) and to have been buried where he lay.

page 200 note 4 The συν- of the preceding verb may perhaps be felt to cover ἦ also.

page 200 note 5 I do not know whether the aor., βλέΦας which seems odd, could mean having acquired a black eye. I feel in any case some temptation to write δέ μαυρά or δ' ἀμαυρά.

page 200 note 6 Meineke, following Toup, wrote τριχιδιφερίας, but I do not know what the word should mean. Διφθερίας is an elderly servant in Tragedy (Poll. iv. 137) and a rustic in Comedy (Varro R.R. ii. II). The former had no ὄγκος and long white hair; the comic rustic had a ![]() (Poll. iv. 147). Possibly τρίχα διφθρίας, ‘with hair like a δ.'.Βονολήκυθος' is held to mean ‘with nothing but a δήκυθος', an odd compound, but so is αὐτολήκυθος, a word used of κόλακες, (Plut. Mor. 50 c). The oil-flask is a stage-property of parasites (Poll. iv. 120, Plaut. Pen. 124, Stick. 230).

(Poll. iv. 147). Possibly τρίχα διφθρίας, ‘with hair like a δ.'.Βονολήκυθος' is held to mean ‘with nothing but a δήκυθος', an odd compound, but so is αὐτολήκυθος, a word used of κόλακες, (Plut. Mor. 50 c). The oil-flask is a stage-property of parasites (Poll. iv. 120, Plaut. Pen. 124, Stick. 230).

page 200 note 7 Prescott aptly cited Call.fr. 75. 76 ![]() where Callimachus acknowledges a debt to Xenomedes.

where Callimachus acknowledges a debt to Xenomedes.