No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

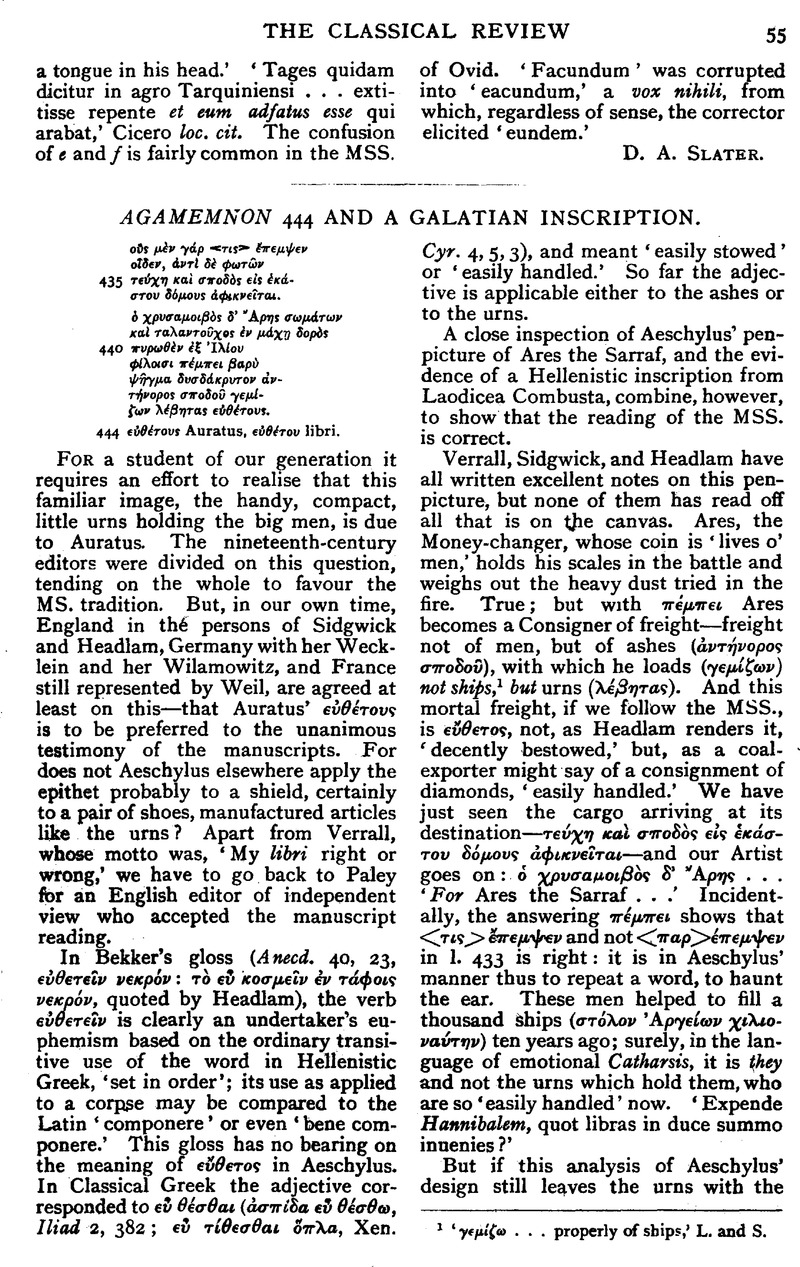

page 55 note 1 ‘γεμζω … properly of ships,’ L. and S.

page 56 note 1 A rare metre in inscriptions. Hexameters and iambic senarii are frequently used to form distichs in Anatolian inscriptions, as also by Gregory of Nazianzus.

page 56 note 2 See Kaibel, Epigr. Graec, index, s.v. εὐσε-βς (five instances). Add ![]() ibid. No. 700;

ibid. No. 700; ![]() , No. 618a;

, No. 618a;![]() No. 649;

No. 649; ![]() Rev. de Phil., 1922, p. 125;

Rev. de Phil., 1922, p. 125; ![]() , Ramsay, , Stud, in E. Rom. Prov., p. 143Google Scholar. With εὐσεβν we also find on inscriptions (see Kaibel, loc. cit.)

, Ramsay, , Stud, in E. Rom. Prov., p. 143Google Scholar. With εὐσεβν we also find on inscriptions (see Kaibel, loc. cit.) ![]() (in a restoration: cf. Kaibel, No. 338), and with μακρων (Kaibel, index, s.v.),

(in a restoration: cf. Kaibel, No. 338), and with μακρων (Kaibel, index, s.v.), ![]() ,

, ![]() , as well as χρος (once in a Christian inscription of Rome; see below). I know no other epigraphical instance of χώρα in such expressions. In Rev. de Phil. I expressed a suspicion, founded on its tone and on the name Philemon, that the Laodicean inscription is a Christian epitaph of the disguised pre-Constantinian type. I find a further hint of Christian feeling in the substitution of the Carphyllidean χώρη for the normal pagan χρος. The earliest Christian inscriptions of Asia Minor (and the present inscription is hardly later than the early third century) are characterised by a tendency to avoid expressions which had associations with pagan religion: see Ramsay, , C. B. Phr., pp. 488 ff.Google Scholar The fact that the form χρος is not used in the N.T. is probably without significance in this connexion; on the other hand, its use by a writer like Gregory Nazianzen in a context which recalls its pagan use(Poems) II. 48,

, as well as χρος (once in a Christian inscription of Rome; see below). I know no other epigraphical instance of χώρα in such expressions. In Rev. de Phil. I expressed a suspicion, founded on its tone and on the name Philemon, that the Laodicean inscription is a Christian epitaph of the disguised pre-Constantinian type. I find a further hint of Christian feeling in the substitution of the Carphyllidean χώρη for the normal pagan χρος. The earliest Christian inscriptions of Asia Minor (and the present inscription is hardly later than the early third century) are characterised by a tendency to avoid expressions which had associations with pagan religion: see Ramsay, , C. B. Phr., pp. 488 ff.Google Scholar The fact that the form χρος is not used in the N.T. is probably without significance in this connexion; on the other hand, its use by a writer like Gregory Nazianzen in a context which recalls its pagan use(Poems) II. 48,

![]() is no evidence for its toleration by earlier Christians in eastern Phrygia. In the Christian poetry of Gregory and his like Christianity masquerades, with somewhat grotesque effect, in the guise of a rhapsode or of a tragic actor; Deissmann has remarked somewhere that Nonnus' rendering of the Fourth Gospel into hexameters is a ‘spiritual outrage.’ The later Christian epitaphs of Asia Minor partake of the same character—e.g. Bishop Macedonius of Apollonis in Lydia describes himself (circa A.D. 375) as

is no evidence for its toleration by earlier Christians in eastern Phrygia. In the Christian poetry of Gregory and his like Christianity masquerades, with somewhat grotesque effect, in the guise of a rhapsode or of a tragic actor; Deissmann has remarked somewhere that Nonnus' rendering of the Fourth Gospel into hexameters is a ‘spiritual outrage.’ The later Christian epitaphs of Asia Minor partake of the same character—e.g. Bishop Macedonius of Apollonis in Lydia describes himself (circa A.D. 375) as ![]() (Grégoire. Recueil, No. 333 bis). With this contrast

(Grégoire. Recueil, No. 333 bis). With this contrast ![]() and

and ![]()

![]()

![]() (or should it be [δ]ςιν, from Epic δ?) in two Phrygian epitaphs, the first certainly, the second probably, Christian, and both dating about A.D. 300 (Ramsay, Stud, in E. Rom. Prov., pp. 126, 124). Such expressions exhibit slight but subtle differences from the pagan formulae: they were meant to be

(or should it be [δ]ςιν, from Epic δ?) in two Phrygian epitaphs, the first certainly, the second probably, Christian, and both dating about A.D. 300 (Ramsay, Stud, in E. Rom. Prov., pp. 126, 124). Such expressions exhibit slight but subtle differences from the pagan formulae: they were meant to be ![]() without being overtly Christian. The form χώρα is used by Basil, In Mort. lulit. ch. 2:

without being overtly Christian. The form χώρα is used by Basil, In Mort. lulit. ch. 2: ![]()

![]() . The expression

. The expression ![]() occurs in a Christian inscription of Rome (Kaibel, No. 733): the above remarks of course apply only to Asia Minor. Salutations (εὐψχει) are found on Christian as well as on pagan epitaphs (Ramsay, , C. B. Phr., p. 523).Google Scholar

occurs in a Christian inscription of Rome (Kaibel, No. 733): the above remarks of course apply only to Asia Minor. Salutations (εὐψχει) are found on Christian as well as on pagan epitaphs (Ramsay, , C. B. Phr., p. 523).Google Scholar

page 56 note 3 LI. 7, 8:![]()

page 57 note 1 εὔθετον is used in a sepulchral context in an inscription of Cyme, C.I.G. 3524: ![]()

![]() . This reference, which I owe to Mr. E. Harrison, is interesting as showing the use of the word in its ordinary Hellenistic sense in Asia Minor about A.D. I.

. This reference, which I owe to Mr. E. Harrison, is interesting as showing the use of the word in its ordinary Hellenistic sense in Asia Minor about A.D. I.