No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

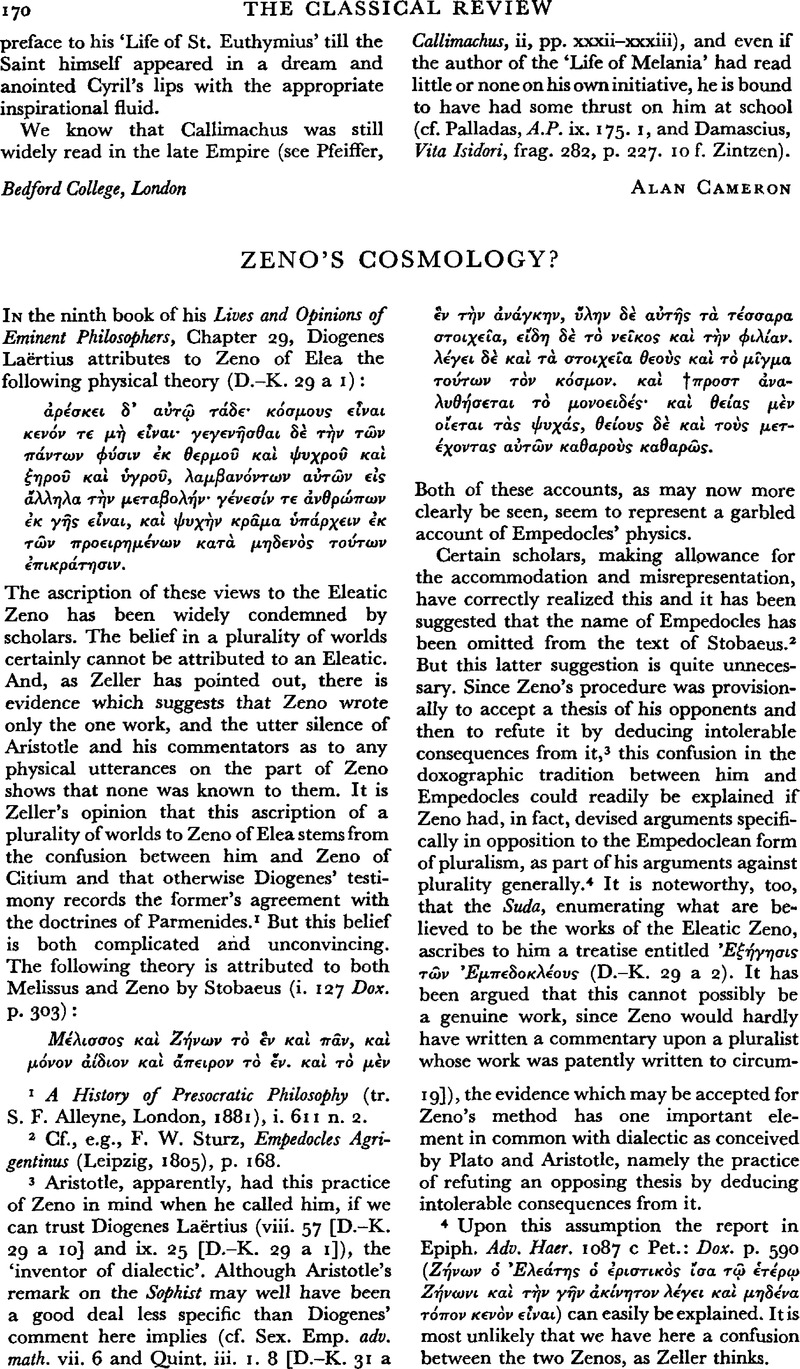

Zeno's Cosmology?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1972

References

1 A History of Presocratic Philosophy (tr.Alleyne, S. F., London, 1881), i. 611 n. 2.Google Scholar

2 Cf., e.g., Sturz, F. W., Empedocles Agrigentinus (Leipzig, 1805), p. 168.Google Scholar

3 Aristotle, apparently, had this practice of Zeno in mind when he called him, if we can trust Diogenes Laërtius (viii. 57 [D.–K. 29 a 10] and ix. 25 [D.–K. 29 a 1]), the ‘inventor of dialectic’. Although Aristotle's remark on the Sophist may well have been a good deal less specific than Diogenes’ comment here implies (cf. Sex. Emp. adv. math. vii. 6 and Quint, iii. 1. 8 [D.–K. 31 a 19]) the evidence which may be accepted for Zeno's method has one important element in common with dialectic as conceived by Plato and Aristotle, namely the practice of refuting an opposing thesis by deducing intolerable consequences from it.

4 Upon this assumption the report in Epiph. Adv. Haer. 1087 c Pet.: Dox. p. 590 (Ζήνων ὁ Ἐλεάτης ὁ ἐριςτικὸς ἴσα τῷ ἑτέρῳ Ζήνωνι καὶ τὴν γῆν ἀκίνητον λέγει καὶ μηδένα τόπον κενὸν εἶναι) can easily be explained. It is most unlikely that we have here a confusion between the two Zenos, as Zeller thinks.