No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 February 2009

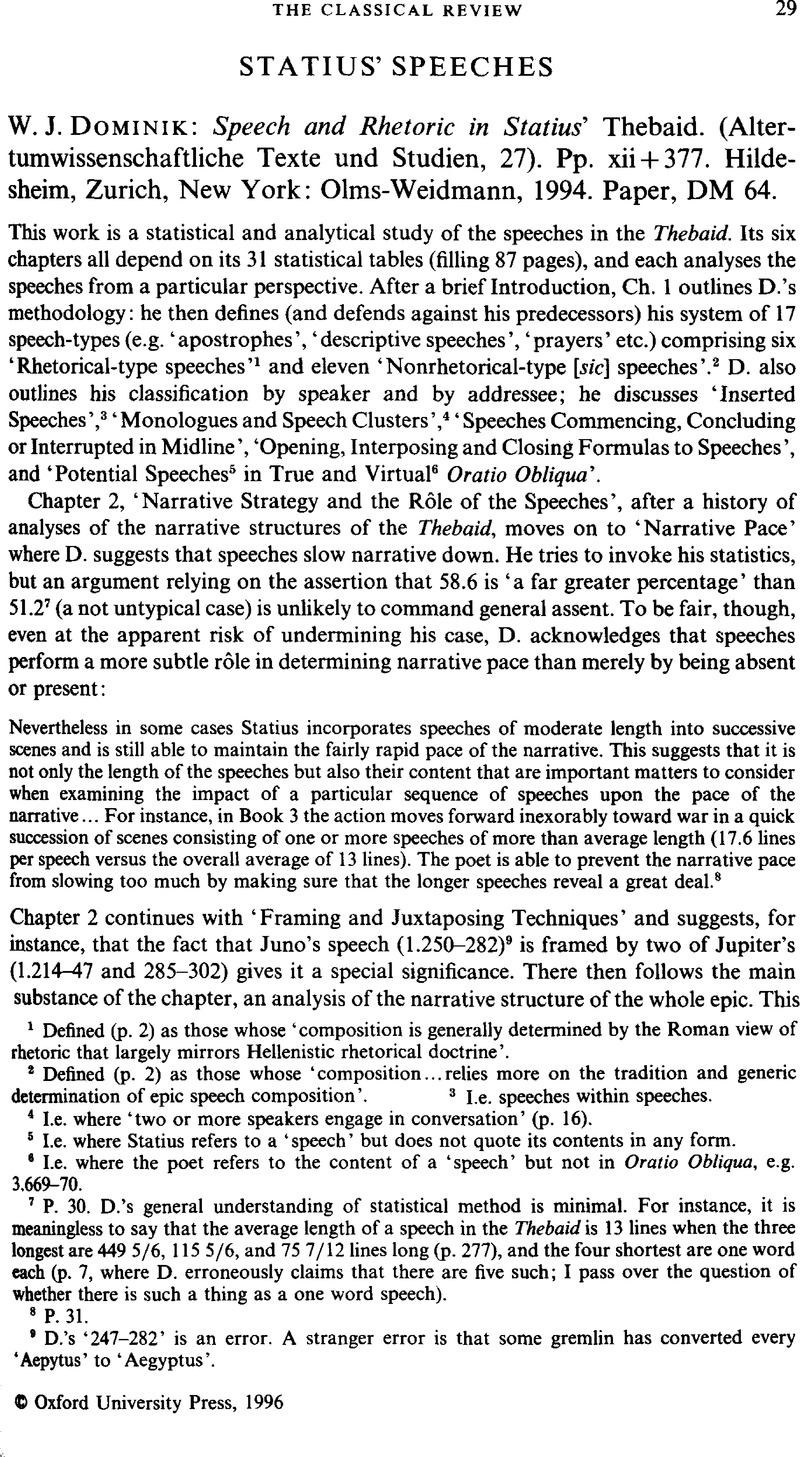

1 Defined (p. 2) as those whose ‘composition is generally determined by the Roman view of rhetoric that largely mirrors Hellenistic rhetorical doctrine’

2 Defined (p. 2) as those whose ‘composition…relies more on the tradition and generic determination of epic speech composition’.

3 I.e. speeches within speeches.

4 I.e. where ‘two or more speakers engage in conversation’ (p. 16).

5 I.e. where Statius refers to a ‘speech’ but does not quote its contents in any form.

6 I.e. where the poet refers to the content of a ‘speech’ but not in Oratio Obliqua, e.g. 3.669–70.

7 P. 30. D.'s general understanding of statistical method is minimal. For instance, it is meaningless to say that the average length of a speech in the Thebaid is 13 lines when the three longest are 449 5/6, 115 5/6, and 75 7/12 lines long (p. 277), and the four shortest are one word each (p. 7, where D. erroneously claims that there are five such; I pass over the question of whether there is such a thing as a one word speech).

8 P. 31.

9 D.'s ‘247–282’ is an error. A stranger error is that some gremlin has converted every ‘Aepytus’ to ‘Aegyptus’.

10 1.1–4.645; 4.646–6.94; 7.1–12.819.

11 P. 41.

12 P. 210.

13 Pp. 245–6.

14 P. 247. Note that of those 20 lines only 9 end in -es or -is and that, of the four that end in -is, one has a short vowel.

15 P. 263.