No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

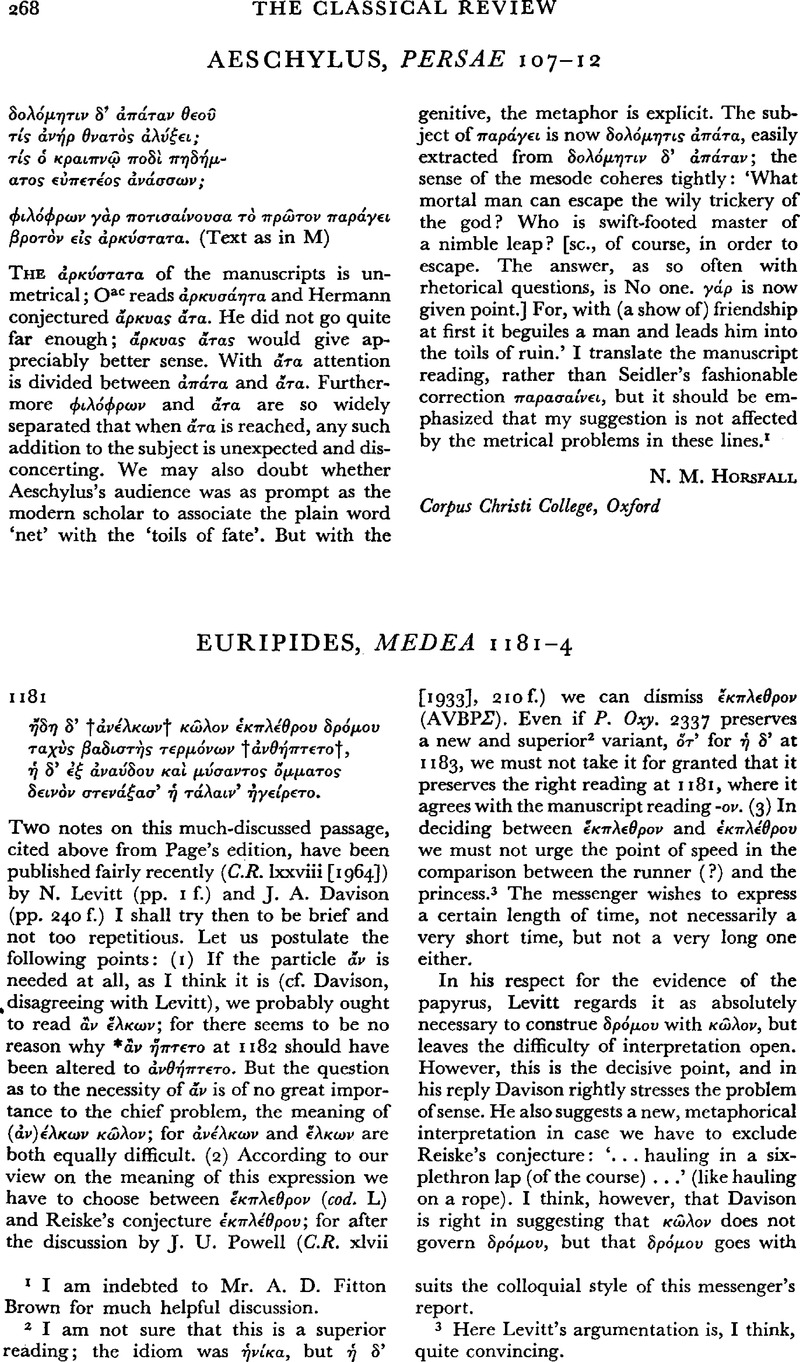

Euripides, Medea 1181–4

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1968

References

page 268 note 1 I am indebted to Mr. A. D. Fitton Brown for much helpful discussion.

page 268 note 2 I am not sure that this is a superior reading; the idiom was ⋯ν⋯κα, but ⋯ δ'suits the colloquial style of this messenger's report.

page 268 note 3 Here Levitt's argumentation is, I think, quite convincing.

page 269 note 1 Cf. also Regenbogen, , Eranos xlviii (1950). 49.Google Scholar

page 269 note 2 Nor is Aristoph. Pax 328 of much help to us: ἓν μ⋯ν οὖν τουτ⋯ (sc. σχ⋯μα) μ' ἔασον ⋯λκ⋯σαι.

page 269 note 3 Page compares Bacch. 1067. For a slower movement π⋯δα ⋯λκειν is used in Soph. Phil. 291 and Eur. Phoen. 303.

page 269 note 4 Davison cites Bacch. 168 κ⋯λον ἄγει as an example of Euripidean singular for plural.

page 269 note 5 Cf. also βαδιστ⋯ς alone = ⋯νος in P. Flor. 376. 23 (iii A.D.), and, βαδιστηλ⋯της ‘driver of riding-donkeys’, in P. Teb. 262 (ii B.C.). I quote these instances from L.S.J.

page 269 note 6 e.g. Steele (the Guardian, 1713, No. 6), speaking of Sir Harry Lizard's particular care for horses: ‘To keep up a breed for any use whatever, he gives plates for the best performing horse in every way in which that animal can be serviceable. There is such a prize for him that trots best, such for the best walker, such for the best galloper, such for the best pacer …’ A close parallel is also furnished by the Swedish ‘gångaren’, word belonging especially to the style of the old folk-songs (‘gångaren grå’).