No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

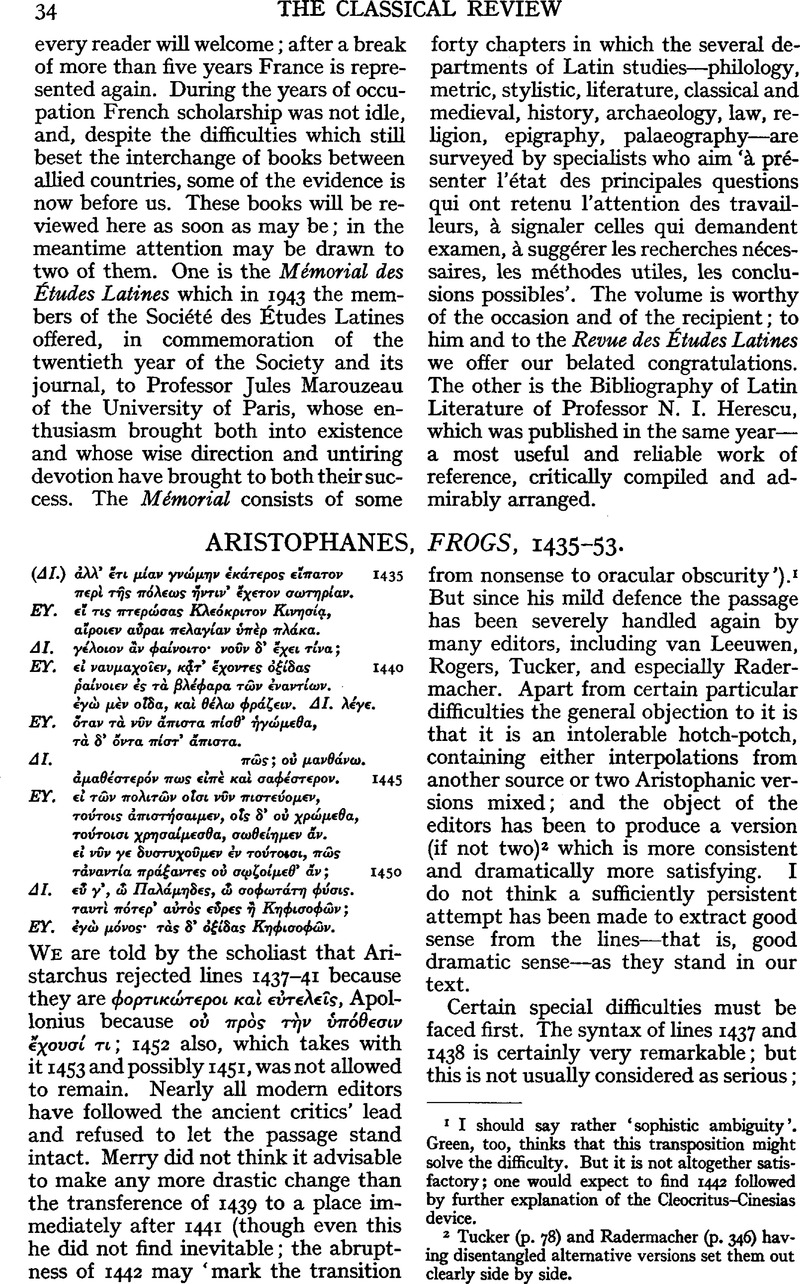

page 35 note 1 I should say rather ‘sophistic ambiguity’. Green, too, thinks that this transposition might solve the difficulty. But it is not altogether satisfactory; one would expect to find 1442 followed by further explanation of the Cleocritus-Cinesias device.

page 35 note 2 Tucker (p. 78) and Radermacher (p. 346) having disentangled alternative versions set them out clearly side by side.

page 35 note 1 e.g. Tucker on 1437 (his 1438). The examples quoted are mostly not so startling as this. Usually the person referred to in the unattached nominative participle can be regarded as the logical subject of the whole sentence; this is not quite the case here, but at least the hypothetical inventor referred to by ns can be regarded as the author of the whole scheme.

page 35 note 2 p. 343.

page 35 note 1 Blaydes, on 1444, says ‘Malim τà νūν δέ πίοσ'’; this makes the sense clearer and spoils the point.

page 36 note 1 While admitting the need for Mr. Gomme's warning (C.R. lii. 97) against attaching too much importance to Aristophanes' own political views in the appreciation of the comedies, I do not agree that on the subject of war and warmongers his views are dramatically unimportant, or that he is primarily dramatizing current feelings among different sections of the community, rather than consistently promoting an anti-war policy. I feel that Aristophanes' own voice can often be heard speaking through the mouth of Dicaeopolis, and that lines such as Ach. 979 express his fixed attitude to war.

page 36 note 2 It is a welcome change to find that Norwood (Greek Comedy, p. 260) calls 959 ff. a ‘magnificent description of realism’; too often, whatever Euripides says in the Frogs, he is assumed to be condemning himself out of his own mouth.

page 37 note 1 Supplices, 244, ![]() I have not overlooked the great difficulty of extracting a dramatist's political—or any other—views from his plays. The principles on which it can be done are expounded and applied to Euripides by, e.g., Decharme, P., Euripide et ľEsprit de son Théâtre, pp. 25 ff.Google Scholar (translation by J. Loeb, pp. 19,20); Appleton, R. B., E. the Idealist, p. xiv.Google Scholar

I have not overlooked the great difficulty of extracting a dramatist's political—or any other—views from his plays. The principles on which it can be done are expounded and applied to Euripides by, e.g., Decharme, P., Euripide et ľEsprit de son Théâtre, pp. 25 ff.Google Scholar (translation by J. Loeb, pp. 19,20); Appleton, R. B., E. the Idealist, p. xiv.Google Scholar

page 37 note 2 Euripides emphasizes the horrors of war rather than the blessings of peace which Aristophanes dangles before his countrymen's eyes; but what could Aristophanes find more sympathetic than the beautiful peace fragment from the Cresphontes, ![]() See Nauck, Trag. Graec. Frag. (1889) 453; note especially the emphasis on festivals—

See Nauck, Trag. Graec. Frag. (1889) 453; note especially the emphasis on festivals—![]()

page 38 note 1 The sabre–rattling type ascribed to Aeschylus' influence in 1016 is hardly one which Aristophanes admires; not to speak of Lamachus (1039). Yet Aeschylus is sometimes treated as if he were the mouthpiece of Aristophanes himself; words spoken by him in rage or blind prejudice are quoted, out of their context, as if they were the considered judgements of Aristophanes; this is very unjust to Aristophanes.