No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

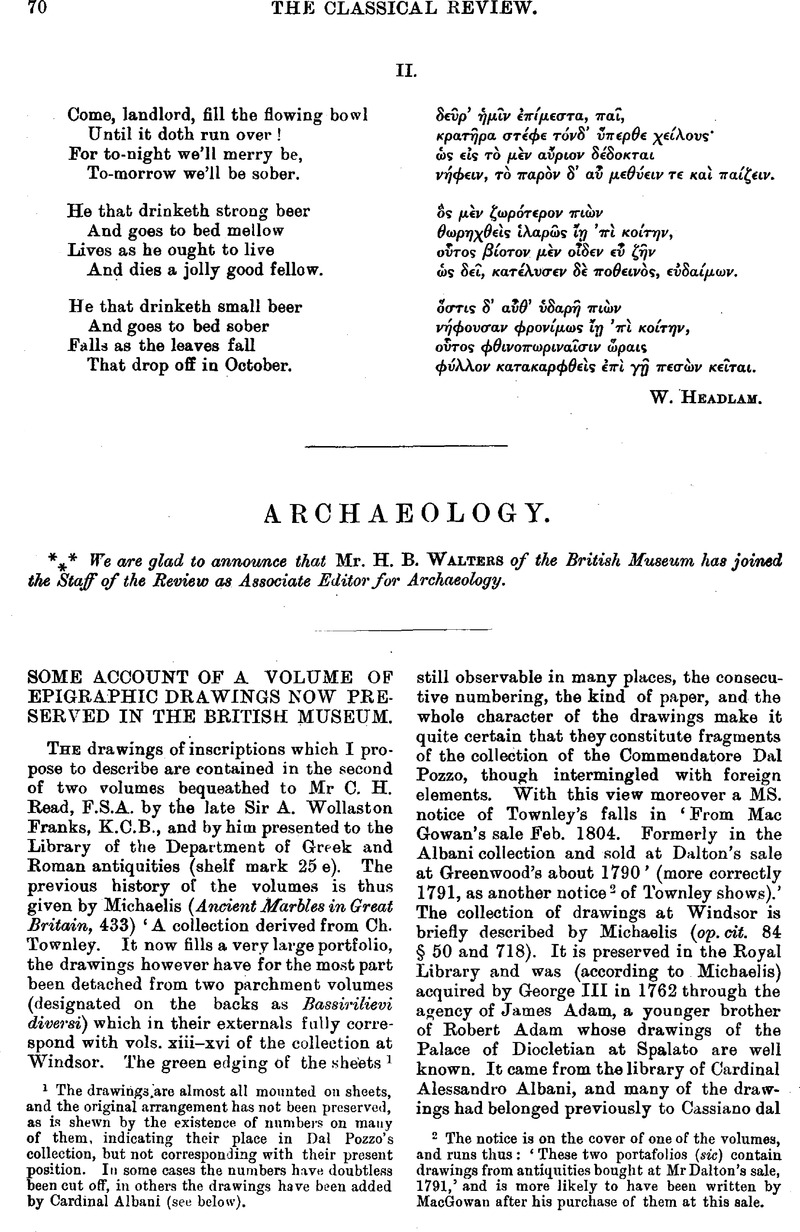

Archaeology

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Other

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1904

References

page 70 note 1 The drawings are almost all mounted on sheets, and the original arrangement has not been preserved, as is shewn by the existence of numbers on many of them, indicating their place in Dal Pozzo's collection, but not corresponding with their present position. In some cases the numbers have doubtless been cut off, in others the drawings have been added by Cardinal Albani (see below).

page 70 note 2 The notice is on the cover of one of the volumes, and runs thus: ‘ These two portafolios (sic) contain drawings from antiquities bought at Mr Dalton's sale, 1791,’ and is more likely to have been written by MacGowan after his purchase of them at this sale.

page 71 note 1 Prof. Robert doubts the correctness of their attribution to Matz (Matz-Von Duhn, iii. 293, note).

page 71 note 2 The numbering of the leaves for which I am responsible (this volume, like the first, having come into the possession of the Museum unbound) attempts as far as possible to preserve the original order.

page 72 note 1 After f. 20 the figure in brackets (where it occurs) denotes the number indicating the place of a drawing in the ‘ museo cartaceo.’

page 72 note 2 The letters (a) (b) etc. denote the different slips which are mounted on the same leaf.

page 73 note 3 The description is copied from Smetius f. 30 (C.I.L. vi. p. xlix. no. xxxvii.) cf. Marangoni Cose Gentilesche ad uso delle chiese p. 175.

page 73 note 1 The inscriptions given on it are C.I.L. vi. 370, 1846, 23282, 24441, and (on the back) Kaibel, I.G.I. 1973.

page 75 note 1 Nearly all the drawings mentioned bear collection numbers.

page 76 note 1 There is one doubtful tradition of an oak-king in Lycia itself. Plut, de def. or. 21 mentions three chiefs of the Solymi—Arsalos Dryos and Trosobios—who were worshipped by the Lycians as σκληρο θεο, being invoked in public and private imprecations. The name Δρος is certainly suggestive of an oak-cult. But Euseb. prep. ev. 5. 5 in his quotation from Plutarch gives the triad as ![]() and their title as σκιροὺς θεος. See Lobeck Aglaoph. p. 1186 n. i. It should be added that a coin of Sagalassus in Pisidia, a city sometimes reckoned as belonging to Lycia (Ptol. 5. 3. 6), shows the head of Zeus wreathed with oak (Overbeck Kunstmyth. Zeus p. 234).

and their title as σκιροὺς θεος. See Lobeck Aglaoph. p. 1186 n. i. It should be added that a coin of Sagalassus in Pisidia, a city sometimes reckoned as belonging to Lycia (Ptol. 5. 3. 6), shows the head of Zeus wreathed with oak (Overbeck Kunstmyth. Zeus p. 234).

page 76 note 2 On the poplar as a mythological equivalent for the oak see C.R. xvii. 181, 273, 407, 418, 419 n. 3.

page 77 note 1 Panofka shrewdly cp. a vase by Euthymides, which shows a strange three-eyed head as a blazon on Hector's shield (Arch. Comm. Paus. p. 30, pl. 3, 15, 15a).

page 78 note 1 Pick die ant. Münz. v. Dacien u. Moesien pl. 5, 7 figures a specimen, on which the eagle has closed wings, additional oak leaves being introduced into the design.

page 78 note 2 The word τμοι is used of ship-timber in an inscr. (Boeckh Urkunden p. 412, 165). In the second cent. B.C. the priest of the Samothracian deities at Tomi had, among other duties, to provide cleft wood for the mystae on a particular day (Michel 704 ![]() ).

).

page 79 note 1 Aeneus, the father of Cyzicus, was son of Stilbe and Apollo (schol. Ap. Rhod. 1. 948). The Thessalian Triopas according to some (Diod. 5. 61) was son of Stilbe and Apollo's son Lapithes. Thus the father of Cyzicus would be brother or half-brother of Triopas, whose name attests the cult of the triple oak-Zeus (supra).

page 80 note 1 e.g. Ael. de nat. an. 3. 26 makes the hoopoe release its young from a nest in the wall, which has been stopped with a patch of mud, by means of a magic herb (cp. Bochart Hierozoïcon ed. 1796 iii. 112, Aristoph. av. 93, 654 f.). Plin. nat. hist. 10. 40 tells a very similar tale of the picus Martius; and Dr. Frazer informs me that the wood-pecker is still credited with the same powers in continental folklore.

page 81 note 1 As such they would pass for Zeus. This may underlie the statement that Polytechnus and Aëdon impiously claimed to love each other more fondly than Zeus and Hera (Ant. Lib. 11).

page 81 note 2 Cp. Aristot. hist. an. 614a 35, schol. Aristoph. av. 480, and the passages cited in C.R. xvii. 412.

page 81 note 3 Zeus Ἄρειος occurs also at Olympia (Paus. 5. 14. 6) and at Iasos in Caria (Overbeck Kunstmyth. Zeus p. 209, Münzt. 3, 11): the former I have identified with a tree-god (C.R. xvii. 271 ff.); the latter was presumably related to the Carian oak-Zeus (ib. p. 415 ff.).

page 82 note 1 Ultimately a compromise was effected between the oak-cult and the vine-cult. In an inscr. from Thessalonica (B.C.H. xxiv. 322) a priestess of Πρινοφρος, the Bearer of the Evergreen-oak, who speaks of herself as θσα and εὐεα, leaves certain vineyards to her θασος, the πρινοφροι: if the conditions of the bequest are not fulfilled, the property is to go to another θασος, that of the δροιοφροι or Oak-bearers. Coins of Thessalonica have a wreath of oak-leaves enclosing the word ![]() (Brit. Mus. Cat. Gk. Coins Macedonia, etc. pp. 108, 113 f.) or of ivy enclosing a bunch of grapes (ib. p. 109) Tzetzes in Lyc. 212 read Φηγαλες, not Φιγαλες, as the epithet of Dionysus, cp. Eust. 664, 48

(Brit. Mus. Cat. Gk. Coins Macedonia, etc. pp. 108, 113 f.) or of ivy enclosing a bunch of grapes (ib. p. 109) Tzetzes in Lyc. 212 read Φηγαλες, not Φιγαλες, as the epithet of Dionysus, cp. Eust. 664, 48 ![]() . The Bacchants in the neighbourhood of Dryoscephalae (C.R. xvii. 270) wear wreaths of oak (Eur. Bacch. 703 cp. 110, 685, 1103).

. The Bacchants in the neighbourhood of Dryoscephalae (C.R. xvii. 270) wear wreaths of oak (Eur. Bacch. 703 cp. 110, 685, 1103).

page 82 note 2 According to Tzetz. Lyc. 492, Malalas 6. 209, Althaea had eaten a spray of olive before Meleager's birth and borne it along with him: on this his life depended. The olive was elsewhere a substitute for the oak (C.R. xvii. 273).

page 82 note 3 Ἄργος, the ‘ Bright’ one, obviously corresponds in meaning to Ζες, the ‘ Bright’ one; cp. ![]() (Emped. 160),

(Emped. 160), ![]() (Il. 19. 121, alib.). The word ργς denoted ‘ a thunderbolt,’ and Ἄργης was a Cyclops who forged thunderbolts for Zeus (Eust. 906, 46; 1528, 35).

(Il. 19. 121, alib.). The word ργς denoted ‘ a thunderbolt,’ and Ἄργης was a Cyclops who forged thunderbolts for Zeus (Eust. 906, 46; 1528, 35).

page 83 note 1 Cp. the species termed δρυΐνας or δρϊνος (Steph. Thes. s.v.).

page 83 note 2 Δρυοπς was subsequently named Δωρς (Hdt. 8. 31), the ‘ Oak-land ’ (Schrader Reallex. p. 164); so that the importance of the oak in Central Greece is incontestable. Indeed, one great division of the Greek race, the Dorians, derived their name from it.

page 84 note 1 Triptolemus crossed the world in his car ‘ borne aloft through the sky’ (Apollod. 1. 5. 2). The car was borrowed by Antheas, who fell off and was killed (Pans. 7. 18. 3). This certainly recalls Phaethon and the solar car. Triptolemus was sometimes said to be the son of Oceanus and Ge (Pherecyd. ap. Apollod. 1. 5. 2); and was often regarded as a judge in the Underworld (Plat. ap. 41A. Preller-Robert p. 770 n. 3). An Argive legend made him the brother of Eubuleus, son of Trochilus ‘ the Wren’ a priest of the mysteries at Argos (Paus. 1. 14. 2). Thus he had connexions with sky, sea, and earth. The shape of his car, a wheeled seat, invites comparison with the sella curulis, which was originally a chariot (Gell. 3. 18. 4, alib., cp. Babelon Monn, de la Rép. ii. 532) used to prevent the sacrosanct person from contact with the ground (cp. Frazer G.B. 2 iii. 202 f.).

page 84 note 2 Bötticher Baumkultus p. 75, fig. 63, published a ‘hero-relief’ from Athens, which represents a young warrior standing beside his horse and feeding a large snake coiled round an oak-tree. On the tree are perched two small birds (wood-peckers ?). It is also decked with armour (sword, spear, shield, breast-plate). A boy approaches with a helmet in one hand and a palm-branch in the other. In the background is a pillar supporting a vase.

page 84 note 3 On the cult of Codrus in the temenos of Neleus and Basile (Ditt.2 550) see Kern in Pauly-Wissowa iii. 41 f.

See further C.R. xvii. 415.

page 85 note 1 The coin representing Zeus Ϝελχνος is a coin of Φαιστς. Does this fact throw any light on the derivation of the puzzling name Ἤφαιστος ? It is at least a singular coincidence.

page 85 note 2 The name is probably a lengthened form of Δα, on the analogy—as Mr. P. Giles has suggested—of Διονσια. There was a festival Δα at Teos (Michel 1318): cp. the Athenian Πανδα.

page 86 note 1 Miss Harrison in her interesting chapter on ‘The Diasia’ (Prolegomena p. 12 ff.) regards the of Zeus as grafted upon that of an ancient serpentdeity Meilichios: but she admits that any educated Greek of the fifth century B.C. would have said ‘ Zens Meilichios is Zeus in his underworld aspect—Zeus-Hades.’

page 86 note 2 Eust. 83, 25 ![]() hits upon a somewhat similar etymology. I owe the passage to Miss Harrison.

hits upon a somewhat similar etymology. I owe the passage to Miss Harrison.

page 88 note 1 If it be objected that the Arcadians regarded Demeter as the wife of Poseidon (Paus. 8. 37. 9), I should reply that Poseidon was but the local form of Zeus. Pausanias in this very passage goes on to say that Despoina, the daughter of Demeter by Poseidon, corresponded to Cora, the daughter of Demeter by Zeus.

page 88 note 2 The local tradition, mentioned by Dr. Frazer, ‘ that these are the bones of men whom the ancients caused to be here trampled to death by horses, as corn is trodden by horses on a threshing-floor’ is deserving of attention. We have found a parallel to it in the myths of Lycurgus and Hippolytus-Virbius (supra).

page 89 note 1 Goerres Studien zur griech. Mythol. p. 17 identifies Phegeus with an oak-Zeus.

page 91 note 1 The marble and tufa figures described by Homolle in B.C.H. xx. pp. 649–652, xxy. pp, 457–515 with 10 plates, do not, it seems to me, belong to the temple under discussion.

page 92 note 1 This date is rejected by Ed. Meyer, Geschichte des Alterthums, v. preface, as ‘ völlig unmöglich.’