No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

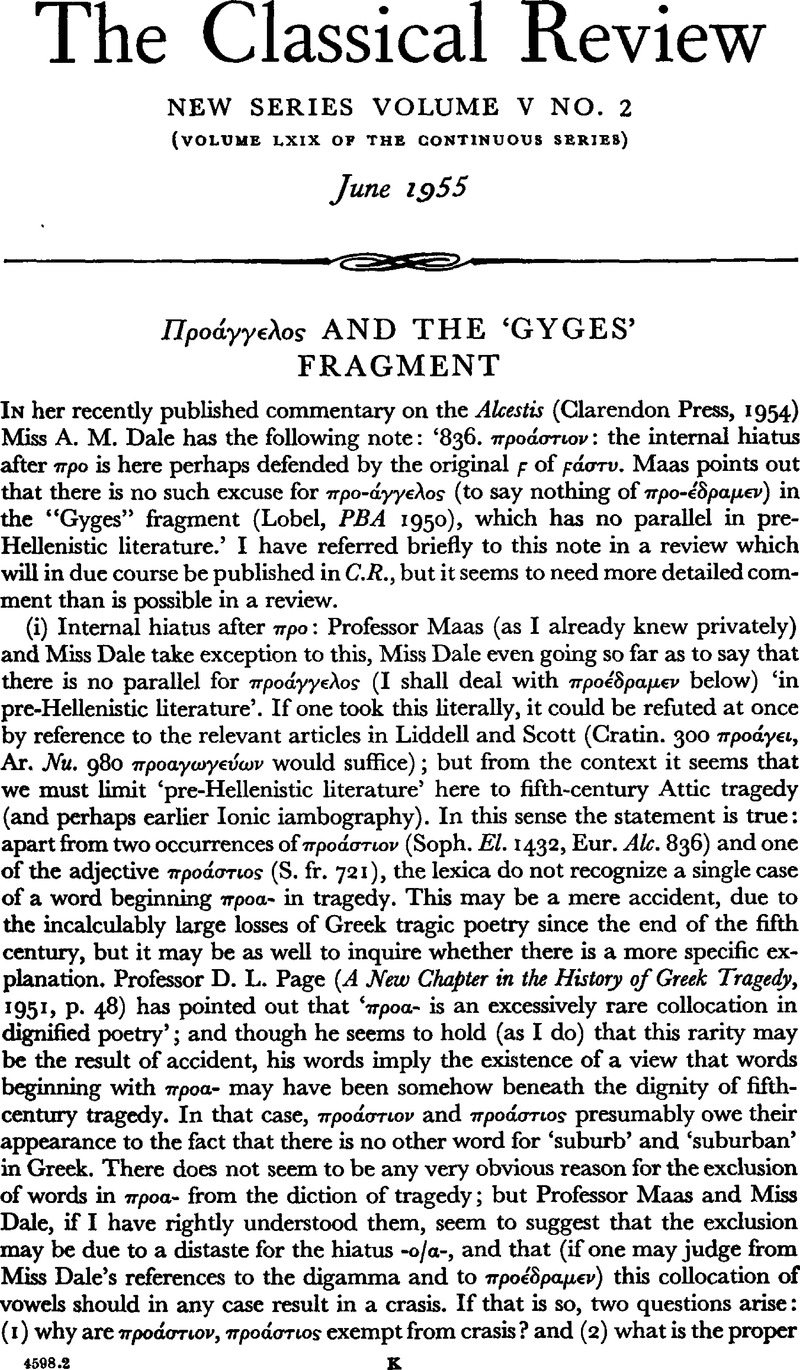

Προάγγελος and the ‘Gyges’ Fragment

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1955

References

page 130 note 1 Cf. Schwyzer, , Griechische Grammatik, i (1939), P. 402Google Scholar, quoting προέρχομαι, πρόεδρς; this, pace Mr. Lobel (op. cit., p. 8) seems to be the explanation of Ant. 208 ![]() . (φροῦδος shows that a rough breathing is not an obstacle to crasis; προορῶ is protected by the fact that crasis would produce the ambiguous φρουρῶ.) προὔργου is not a true compound, and is outside the scope of the rule.

. (φροῦδος shows that a rough breathing is not an obstacle to crasis; προορῶ is protected by the fact that crasis would produce the ambiguous φρουρῶ.) προὔργου is not a true compound, and is outside the scope of the rule.

page 130 note 2 The connexion of πρανής (πρηνής) with προ− (cf. ἀπ−ηνής), still supported by Schwyzer, op. cit. ii (1950), p. 505, nn. 2, 6, is very uncertain (cf. Boisacq, s.v. followed by Hofmann); πρηγορεών (προ+√ἀγείρω) is a technical term, presumably taken over from Ionic.

page 130 note 3 Cf. Lloyd-Jones, H., Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. n.s. ii (1952/1953), pp. 36–43Google Scholar; the evidence is collected by Page, op. cit., p. 44, n. 23.

page 131 note 1 Lucr. v. 737–8 Bailey; as Lachmann felt, Pontanus' ueris for Veneris is really preferable, since the following Zephyri is otherwise left unexplained; N. P. Howard's reference to iv. 1057 uoluptatem praesagit muta cupido in support of Veneris seems, pace Munro and Bailey, out of key with this passage (it has perhaps more affinity with the σιωπή of Musaeus 165).

page 131 note 2 I use this word advisedly, since the one fifth-century parallel (10 Chius fr. 10 Bergk ![]() ) comes from the beginning of a dithyramb.

) comes from the beginning of a dithyramb.

page 131 note 3 Sweating statues are rare in the fifth and fourth centuries (w. 7–9 of the oracle in Hdt. vii. 140 are not evidence that the statues actually sweated, whatever the Pythia thought they should be doing, and the sweating statues at Thebes in 335 are attested only by Diod. xvii. 10. 4), but Aristotle (822a31) and Theophrastus (Hist. Plant, v. 9. 8) mention the phenomenon, and Apollonius Rhodius (iv. 1284–5) speaks of statues sweating blood. Most of the references to this portent, however, are Roman or of the Roman period (see A. S. Pease on Cic. de Div. i. 98 sudauit); the balance of probability therefore inclines to the view that this epigram is late. Mr. B. S. Page, Librarian of the University of Leeds, gave me valuable help with this note.

page 131 note 4 I do not mean by this that we have a right to expect Aeschylus to use a specialized word whenever one was available to him, or that κῆρυξ is not a perfectly proper word for his purpose in the Agamemnon; but where one is forced, as one is in this matter, to depend on the faintest indications, it is surely legitimate to draw attention to all the possibilities.