Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Anyone who seeks to add to the already vast pile of literature dealing with the I.A. must needs feel apologetic, especially if he is conscious that little of what he will say is new. Nevertheless this seems to be one of those occasions when it is necessary to restate old arguments. Recent contributors to the debate about the problems of the opening of the play either fail to realize what the problems are or else attempt to explain away valid criticisms of the text with arguments that are methodologically suspect and parallels which will not hold water.

1 I refer to the following works by author's name alone: England, E.B., The Iphigenia at Aulis of Euripides (London, 1891)Google Scholar; Page, D.L., Actors' Interpolations in Greek Tragedy (Oxford, 1934)Google Scholar; Ed. Fraenkel, , ‘Ein Motiv aus Euripides in einer Szene der neuen Komödie’, Studi in onore di U.E. Paoli (Firenze, 1955), pp. 293–304Google Scholar (= Kleine Beiträge zur klassischen Philologie (Rome, 1964) i. 487–502).Google Scholar The doxography of the problem given by England (pp. xxi - xxv) may be supplemented by consulting the works of Valgiglio, Mellert-Hoffmann, and Knox (see below notes 18 and 19) and the dissertation of Schreiber, H.M., Iphigenies Opfertod (Frankfort, 1963). 1 feel no real disquiet about presenting a discussion of the prologue in isolation from the other problems of the play (see Walter Nestle, Die Struktur des Eingangs, Vorwort) since I shall be making very few positive assertions and also because I sense that the problems of the prologue may indeed be special.Google Scholar

2 Friedrich, W.H., Hermes 70 (1935), 72Google Scholar ff. provides one of them. His interpretative essay contains a defence of the paradosis which seems to me to be liable to the same kind of criticism as has been levelled against Voigtländer's, H.-D. defence of Eur. Med. 1056–80Google Scholar against Gerhard Müller's attack on it (see Reeve, M.D., CQ N.S. 22 (1972), 57). The same might be said of the recent article by van Potterbergh (see below, note 18.Google Scholar

3 ‘The Prologue of the phigenia at Aulis’, CQ N.S. 21 (1971), 343–64.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

4 Willink is not the first to seek to account for the difficulties of the prologue by positing an accident of transmission. Hartung's suggestion (accepted both by Hermann, , Opuscula VIII. 218 f., who rewrites 107 ff. so that they link properly with 1 ff., and with some further modifications by England) that the original order was 49–104, 1–48, lacuna, 115 ff. (see his 183 5 edition, p. 85) was taken up by K. Bohnhoff who believed, unlike Hartung, that the dislocation had come about by accident (K. Bohnhoff, Der Prolog der Iphigenie in Aulis des Euripides, Programm des stadtischen Gymnasium in Freienwalde, 1885). The Hartung transposition which has a good deal more to be said for it than Willink's is liable to the objections raised against Willink on p. 12.Google Scholar

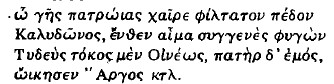

5 ![]()

![]() is all that Proklos tells us (p. 104.17 Allen). Th letter-motif looks characteristically Euripidean (‘ce moyen romanesque’ says Jouan, Fr., Euripide et les légendes des chants cypriens (Paris, 1966), p. 284, n.2). We know of four of his plays apart from this one in which letters played a part (Hippolytos, Stheneboia, Palamedes, and I.T.). The only other source which mentions a letter in connection with the summoning of Iphigeneia is Dictys Cretensis 1.20. Ulysses on his own initiative takes ‘falsas litteras tamquam ab Agamemnone’ to Clytaemnestra telling he that Achilles will not go to Troy unless as promised he is given the hand of Iphigenei This is no doubt a contamination of the traditional version with the letter-motif taken from Euripides.Google Scholar

is all that Proklos tells us (p. 104.17 Allen). Th letter-motif looks characteristically Euripidean (‘ce moyen romanesque’ says Jouan, Fr., Euripide et les légendes des chants cypriens (Paris, 1966), p. 284, n.2). We know of four of his plays apart from this one in which letters played a part (Hippolytos, Stheneboia, Palamedes, and I.T.). The only other source which mentions a letter in connection with the summoning of Iphigeneia is Dictys Cretensis 1.20. Ulysses on his own initiative takes ‘falsas litteras tamquam ab Agamemnone’ to Clytaemnestra telling he that Achilles will not go to Troy unless as promised he is given the hand of Iphigenei This is no doubt a contamination of the traditional version with the letter-motif taken from Euripides.Google Scholar

6 [Apollodoros] Epitome 3.22Google Scholar. Possibly this is the Kypria version. See Zieliński, T., Tragodumenon Libri Tres (Warsaw, 1925), p. 256.Google Scholar

7 Hyginus 98.3 Rose. It has been suggested that Sophocles lies behind this (Nauck, , TGF 2 p.197Google Scholar, Zieliński, , pp. 265 ff). We know for certain that Odysseus appeared in his play since our one fragment (284N) is introduced as spoken by him. Eur. El. 1020–3 seems to presuppose yet another version where Agamemnon personally takes Iphigeneia to Aulis (cf. also Eur. I. T. 370–1). See in general Preller-Robert, ii. 1100 ff.Google Scholar

8 On pauses in the action in tragedy and the illegitimate practice of editors and commentators in introducing them see Oliver Taplin, , HSCP 76 (1972), 57Google Scholar and n.2. Murray mistakenly introduces one after 48 because he refuses to accept Reiske's obviously correct transposition of 117 f. to follow this line. Had Agamemnon broken off at this point ‘grauiter commotus’, either he would have said ‘I cannot go on’, (cf. Eur. Or. 671 ff.) or else the old man would have commented on his sudden silence (cf. Soph, . Phil. 730–1Google Scholar, 805). ‘When a Greek tragedian means something to be important or significant, then he draws his audience's attention to it’, Taplin, , op cit., p. 97.Google Scholar

9 ‘Nihil autem fere fit in Graecorum tragoediis comoediisque quin fieri simul indicetur oratione’, Haupt, M., Opuscula 2Google Scholar.460. See above all Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, T. von, Die dramatische Technik des Sopbokles, pp. 140Google Scholar ff. and also Spitz-barth, A., Untersuchungen zur Spieltechnik der griechische Tragödie (Winterthur, 1946), pp. 39Google Scholar ff., Fraenkel, , Aesch. Ag., p. 642Google Scholar; Steidle, W., studien zum antiken Drama (Munich, 1968), pp. 22Google Scholar f., Zwierlein, O., Die Rezitationsdramen Senecas (Meisenheim am Glan, 1966) pp. 55Google Scholar ff. (and GGA 1970, 214Google Scholar) and Dingel, J. in Bauformen der griechischen Tragödie (Munich, 1971) p. 355.Google Scholar

10 The tendency is exhibited frequently in the apparatus of the Oxford text (cf. n.8). Perhaps Murray was too familiar with his friend Shaw's stage directions.

11 See p. 14.

12 Willink considers it possible that something may have dropped out before 97 and argues that his case does not stand or fall with the acceptance or rejection of his emendation. His attempts to make ![]() do double duty (connecting for the audience this line with 96 and emphasizing [for the old man]

do double duty (connecting for the audience this line with 96 and emphasizing [for the old man] ![]() ) gain no support from Denniston, Greek Particles, p. 238, and the Republic passage he cites as a parallel.Google Scholar

) gain no support from Denniston, Greek Particles, p. 238, and the Republic passage he cites as a parallel.Google Scholar

13 I hardly think that many will accept Willink's assertion that these words do not necessarily imply that Agamemnon is standing and that they do not exclude the possibility that he is sitting at a writingdesk (353). In any case one expects a Greek prince to write with his tablets ![]()

14 Cf. Plaut, . Mil. 200 ff.Google Scholar

15 See England on 4 and 5. A.E. Housman demonstrated once and for all that 7-8 was not the old man's answer to a question in ![]()

![]() (CR 28 (1914), 267Google Scholar = The Classical Papers of A.E. Housman (Cambridge, 1972), ii. 886).Google Scholar

(CR 28 (1914), 267Google Scholar = The Classical Papers of A.E. Housman (Cambridge, 1972), ii. 886).Google Scholar

16 ![]() with a verb of motion meaning ‘out of’ as at line 1117 of this play.

with a verb of motion meaning ‘out of’ as at line 1117 of this play.

17 ‘The writing had been done nar’, ![]()

![]() and he has not ceased to keep the letter in his hand now that the morning was approaching. The present tenses do not so much express what he is doing at the moment as what he has been doing for some time past', Paley on 36.

and he has not ceased to keep the letter in his hand now that the morning was approaching. The present tenses do not so much express what he is doing at the moment as what he has been doing for some time past', Paley on 36.

18 Ritchie, W., The Authenticity of the Rhesus of Euripides, pp. 102Google Scholar f., thinks the prologue can stand as long as we take out 106–14 (in that case ![]() in 117 takes up 104 f. which is surely out of the question). Valgiglio, E., RSC 4 (1956), 174Google Scholar ff. thinks that Euripides wrote what we have, but accepts that it is possible that he did not put the finishing touches to his work, hence the contradiction between 106 ff. and 124 ff. Rome, A., ‘Sur la date de composition de L'Iphigénie a Aulis d'Euripide’, Miscellenea G. Mercati IV (Studi e testi 124) 1956Google Scholar, 13–26, like Webster, T.B.L., The Tragedies of Euripides (London, 1967) 258Google Scholar, accepts without question that the present prologue is Euripidean. Most of Mellert-Hoffmann's, GudrunUnter-suchungen zur “Iphigenie in Aulis” des Euripides (Heidelberg, 1969)Google Scholar is devoted to a defence of the prologue as it stands. On this work see Diggle, J., CR N.S. 21 (1971), 178–80Google Scholar. The latest defence of the paradosis I know of is that of Pottelbergh, R. van, L'Antiquite classiqué 43 (1974), 304–8.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

in 117 takes up 104 f. which is surely out of the question). Valgiglio, E., RSC 4 (1956), 174Google Scholar ff. thinks that Euripides wrote what we have, but accepts that it is possible that he did not put the finishing touches to his work, hence the contradiction between 106 ff. and 124 ff. Rome, A., ‘Sur la date de composition de L'Iphigénie a Aulis d'Euripide’, Miscellenea G. Mercati IV (Studi e testi 124) 1956Google Scholar, 13–26, like Webster, T.B.L., The Tragedies of Euripides (London, 1967) 258Google Scholar, accepts without question that the present prologue is Euripidean. Most of Mellert-Hoffmann's, GudrunUnter-suchungen zur “Iphigenie in Aulis” des Euripides (Heidelberg, 1969)Google Scholar is devoted to a defence of the prologue as it stands. On this work see Diggle, J., CR N.S. 21 (1971), 178–80Google Scholar. The latest defence of the paradosis I know of is that of Pottelbergh, R. van, L'Antiquite classiqué 43 (1974), 304–8.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

19 Yale Studies in Classical Philology 22 (1972), 239–61.Google Scholar

20 Knox sets up and attempts to knock down ‘eleven counts against the manuscript prologue’, (241). This seems to me to obscure the issue since some points are obviously more weighty than others. My first point corresponds to his second and third points, my second to his fifth.

21 They are firmly restated by Fraenkel, (298, 301, n.l). See also England, pp. xxiii-iv.Google Scholar

22 Knox tries to answer Page who also makes this objection (256) by arguing that he is applying too rigid a standard of realism and by comparing other prologues where the speaker is not alone on stage. But there is a great difference between a prologue speaker like lolaos drawing our attention to a tableau on stage and Agamemnon here replying to a request from his dialogue partner by delivering a speech over his head and at the audience. For this the ‘messenger’, speech is scarcely an analogy. It is admittedly highly stereotyped and formal but it does provide information intended equally for the people on stage and the audience. I.A. 695–6 which Knox also adduces as a parallel may be unnatural, but it is at least a genealogy produced in response to a request for a genealogy.Google Scholar

23 It is for them, but does not admit that they are present. See my article ‘Audience Address in Greek Tragedy’, CQ N.S. 25 (1975), 22 f.Google Scholar

24 The prologues of Euripides which begin with more than one person on stage are those ot Hkld., Hik., Her., Tro., and Or. In each play the prologue-speaker refers in the third person to the others who happen to be on stage, using a deictic pronoun (Hkld. 11, 24Google Scholar, 40: Hik. 8, 17Google Scholar, 20, 21, 35: Her. 9, 14Google Scholar, 42: Tro. 36; Or. 35). Iolaos', address to the children of Herakles (Hkld.) is distinct from the expository part of the speech.

25 Knox admits this (244).

26 'Der Alte fragt aus einer un-oder voreuripideischen Situation heraus’, op. cit., p. 79.

27 ‘In 106–7 Agam. said “We four alone know ![]() the facts of the plot” [a somewhat question-begging translation, better simply “the present situation” cf. A. Ag. 1406, Eur. Kret. 5] the old man at once assumes that Achilleus is not in the plot … but he also assumes … that Achilleus was at least told that Iphigeneia was coming to marry him … Agamemnon said “K. and O. and M. and I alone know the truth”; the old man thinks “so these four have made a plot. They have told Ach. that Iph. is coming to be his bride”.’, This explanation which reads like E. Bruhn on Sophocles (see Lloyd-Jones, H., CQ N.S. 22 (1972), 215CrossRefGoogle Scholar ff.) treats the play like a record of real events. It is tantamount to cross-examining the characters. The old man is a fictional creation: he has no independent existence. No competent Greek dramatist would force us to make such elaborate inferences (and for what purpose?) about the thought processes of his characters. While the play is being performed there simply is not time to pause and work all this out. Something resembling Page's explanation is to be found in Hutter's, J.B. perfectly useless Über den Prolog und Epilog in Euripides', Tragödie die Iphigenie in Aulis (Munich, 1844), p. 14.Google Scholar

the facts of the plot” [a somewhat question-begging translation, better simply “the present situation” cf. A. Ag. 1406, Eur. Kret. 5] the old man at once assumes that Achilleus is not in the plot … but he also assumes … that Achilleus was at least told that Iphigeneia was coming to marry him … Agamemnon said “K. and O. and M. and I alone know the truth”; the old man thinks “so these four have made a plot. They have told Ach. that Iph. is coming to be his bride”.’, This explanation which reads like E. Bruhn on Sophocles (see Lloyd-Jones, H., CQ N.S. 22 (1972), 215CrossRefGoogle Scholar ff.) treats the play like a record of real events. It is tantamount to cross-examining the characters. The old man is a fictional creation: he has no independent existence. No competent Greek dramatist would force us to make such elaborate inferences (and for what purpose?) about the thought processes of his characters. While the play is being performed there simply is not time to pause and work all this out. Something resembling Page's explanation is to be found in Hutter's, J.B. perfectly useless Über den Prolog und Epilog in Euripides', Tragödie die Iphigenie in Aulis (Munich, 1844), p. 14.Google Scholar

28 Knox like Willink takes Barrett's name in vain, quoting with approval his note on Eur, . Hipp. 42. The effect achieved there and at Ion 71 ff. seems to me quite different from what Knox supposes to be happening in I. A. For one thing, deities are speaking those prologues: for another, the statements are applicable for the bulk of the plays, not being corrected immediately as in the I. A.Google Scholar

29 Hennig, H., De Iphigeniae Aulidensis forma ac condicione (Berlin, 1869), pp. 18Google Scholar f. (he is followed by Nauck and Pohlenz). There are objections that may be raised against the deletion, most notably the fact that 13 3 ff. is a better response to 124–3 2 than to 123 (see Wecklein, N., Zeitschrift für die öst. Gymnasien 29 (1878), 728).Google Scholar

30 Note too the first words of the chorus on entering, ![]()

![]() 164 ff. Willink's arrangement heightens the redundancy. ‘Here in Aulis’, says the old man at 14 and this follows

164 ff. Willink's arrangement heightens the redundancy. ‘Here in Aulis’, says the old man at 14 and this follows ![]() 81. Similarly the frequent repetition of Agamemnon's name (1, 13, 30, 133) seems unnecessary since, on Willink's arrangement, Agamemnon's identity has been established since the second line of the play.

81. Similarly the frequent repetition of Agamemnon's name (1, 13, 30, 133) seems unnecessary since, on Willink's arrangement, Agamemnon's identity has been established since the second line of the play.

31 It is not the mere repetition of the place name that strikes one as redundant (Thebes and the Thebans are mentioned just as frequently in the prologue of Bakcbai, , 1, 23Google Scholar, 48, 50); it is the appearance of the name twice in conjunction with deictic words (![]() 14

14 ![]() 82). This is not Euripidean technique – in the Ba. prologue there is always a reason for the mention of the town or the people. In our passage the old man need not have mentioned Aulis in 14; he could simply have said ‘here’. The repetition of place names at Eur, . Hipp. 12Google Scholar and 29 and Hek. 8 and 33 at first sight looks like a parallel for what we have here. In each case, however, when the place name is repeated it is to distinguish this land from another land that has been or is about to be mentioned, in the first instance Trozen being distinguished from Athens, in the second the Chersonese from Troy. Editors and commentators tend to claim that expository elements in prologue speeches are repeated in order that anyone inattentive enough to have missed the first mention of them may be put in the picture (e.g. Dodds on Eur, . Ba. 53–4Google Scholar commenting on the emphasis Dionysos appears to lay on his human disguise). This is not at any rate the case in Euripides with regard to the naming of the locale. In Alk. we learn from the first line that this is Admetos', house, but there is no further specification in the prologue. One mention of the locale is sufficient for the nurse in Medea (10) and for Iolaos (Hkld. 38), Aithra, (Hik. 2Google Scholar), Iokaste, (Phoin. 4Google Scholar), and Elektra, (Or. 46 N.B. the delay). In most of these cases and in other prologues there are other incidental details which suggest where the play is taking place, but their mention is not primarily a reminder to the audience: e.g. at Andr. 22 where the audience has learned the locale from 16 f. the repetition can hardly be intended as a reminder so soon after the first mention. Rather it is there to make clear the status of Peleus.Google Scholar

82). This is not Euripidean technique – in the Ba. prologue there is always a reason for the mention of the town or the people. In our passage the old man need not have mentioned Aulis in 14; he could simply have said ‘here’. The repetition of place names at Eur, . Hipp. 12Google Scholar and 29 and Hek. 8 and 33 at first sight looks like a parallel for what we have here. In each case, however, when the place name is repeated it is to distinguish this land from another land that has been or is about to be mentioned, in the first instance Trozen being distinguished from Athens, in the second the Chersonese from Troy. Editors and commentators tend to claim that expository elements in prologue speeches are repeated in order that anyone inattentive enough to have missed the first mention of them may be put in the picture (e.g. Dodds on Eur, . Ba. 53–4Google Scholar commenting on the emphasis Dionysos appears to lay on his human disguise). This is not at any rate the case in Euripides with regard to the naming of the locale. In Alk. we learn from the first line that this is Admetos', house, but there is no further specification in the prologue. One mention of the locale is sufficient for the nurse in Medea (10) and for Iolaos (Hkld. 38), Aithra, (Hik. 2Google Scholar), Iokaste, (Phoin. 4Google Scholar), and Elektra, (Or. 46 N.B. the delay). In most of these cases and in other prologues there are other incidental details which suggest where the play is taking place, but their mention is not primarily a reminder to the audience: e.g. at Andr. 22 where the audience has learned the locale from 16 f. the repetition can hardly be intended as a reminder so soon after the first mention. Rather it is there to make clear the status of Peleus.Google Scholar

32 On Agamemnon's failure to name himself see p. 18.

33 The prologue of Soph. Ant. is a close parallel for the anapaestic opening of I.A. For the motif of people coming out of the stage building to hold a secret conversation (which is not at all unrealistic in the Greek world) see Calder, W.M. III, GRBS 9 (1968), 392, n.18 whose remarks answer England's question (p.13) ‘if [the old man was in the tent] why did Ag. call him and speak to him?'Google Scholar

34 Cf. Soph, . Ant. 1 (Antigone names Ismene) and 11 (Ismene begins by naming Antigone).Google Scholar

35 For this delay in the trimeters compare the prologue of Orestes.

36 Willink claims that ![]()

![]() is technically improper unless the skene is already identifiable as Agamemnon's headquarters at Aulis. It is hard to see how the identification could be made if line 1 were the first line of the play'. This is arbitrary and unconvincing.

is technically improper unless the skene is already identifiable as Agamemnon's headquarters at Aulis. It is hard to see how the identification could be made if line 1 were the first line of the play'. This is arbitrary and unconvincing.

31 In Ion much is made for atmospheric purposes of the time, dawn, but this comes in the ‘Affektiv’, part of the prologue, Ion's anapaestic entry, rather than in the expository prologue by Hermes. See the following note.

38 So Friedrich, p. 94Google Scholar, Willink, p. 346Google Scholar, and Knox, p. 245Google Scholar. The fact that on the present arrangement expository material is divided between the iambic ‘prologue’, and the anapaests argues against the arrangement being Euripidean (see Imhof, M.Bemerkungen zu den Prologen der soph. u. eur. Tragödien (Winterthur, 1957), pp. 104 f. – one makes Nestle's distinction here between exposition of ‘Stimmung’, and of ‘Handlung’: in the Ion prologue Hermes deals with the latter, Ion in his anapaests gives us the former. In I.A., however, ‘Handlung’, spreads over into the anapaests).Google Scholar

39 Also, if one does not believe that the plot and the prologues of the play were conceived by one and the same person, one is not compelled to suppose that the person who composed the anapaestic prologue felt the same urge towards the full exposition of the themes of the play as the person who devised the plot might have felt.

40 Σ Aristoph, . Frogs 67.Google Scholar

41 Recent expressions of this belief, lowever, are to be found in Conacher, D.J., Euripidean Drama (Toronto, 1967), p. 253Google Scholar, n 11. and in Lesky, A., Die tragische Dichung der Hellenen3 (Göttingen, 1972), 494.Google Scholar

42 Since there are degrees of incomileteness it is always possible to argue that he composer of the prologue was able to ise some lines written by Euripides and that even if the structure of the prologue owes lothing to Euripides some of his verses are preserved in it.

43 The motives of the interpolator in lypothesis 1 might seem a trifle obscure perhaps one should not worry too much about the motives of interpolators – see Reeve, M.D., GRBS 13 (1972), 25. One might perhaps conceive of a person who, confronted by a Euripidean play which unusually lacked an expository prologue, felt the need to supply one and hit upon the idea of inserting it within the anapaestic dialogue since there was scarcely any other place where it might go. By doing so he failed to realize that he was producing something even more unEuripidean than what he had found before he went to work.Google Scholar

44 I would not agree with Knox, (pp. 259 f.) that the prosecution presents a much greater demand than the defence in this case.Google Scholar

45 Willink's objection ‘would not an early fourth century audience have objected to the total cutting and replacement of (in effect) the first scene of a well-known prizewinning masterpiece’, (345) betrays a naïve trust in the memories of audiences and in the integrity of actors. If we accept Wila-mowitz's assertion that Eur, . Hek. 73–8Google Scholar and 90–7 were written by an actor who wanted the play to begin with Hekabe's anapaestic entrance rather than the trimeter speech of Polydoros, we would have a parallel for the suppression of a prologue in a ‘popular’, play (and also for the activity envisaged in hypothesis 4) ). Wilamowitz's deletion is certain (Hermes, 44 (1909), 446 – 9Google Scholar = Kleine Schriften IV. 225–8Google Scholar; see also Biehl, W., Philologus 101 (1957), 55–62CrossRefGoogle Scholar and Bremer, J., Mnemosyne iv. 24 (1971), 231–50)Google Scholar: one may note as a further argument against 73 ff. the metrical solecism of ![]()

![]() (contrast 88). His suggestion that the interpolator intended to cut the prologue is attractive but not certain (note the popularity of the prologue – it was obviously known to Pacuuius or to Pacuuius', model when he wrote the Iliona). The loss of the iambic prologues of the Rhesos might supply a parallel, but the case is more complicated if one believes, as I do, that the play we have is not Euripides'. One had perhaps best leave out of account the puzzling question of how Euripides', Melanippe Sopbe began (see Wilamowitz, , Kleine Schriften 1Google Scholar.449 and P.Oxy.2455 fr.l and Haslam, M.W., GRBS 16 (1975), 171.Google Scholar

(contrast 88). His suggestion that the interpolator intended to cut the prologue is attractive but not certain (note the popularity of the prologue – it was obviously known to Pacuuius or to Pacuuius', model when he wrote the Iliona). The loss of the iambic prologues of the Rhesos might supply a parallel, but the case is more complicated if one believes, as I do, that the play we have is not Euripides'. One had perhaps best leave out of account the puzzling question of how Euripides', Melanippe Sopbe began (see Wilamowitz, , Kleine Schriften 1Google Scholar.449 and P.Oxy.2455 fr.l and Haslam, M.W., GRBS 16 (1975), 171.Google Scholar

46 I am assuming, perhaps without justification, that IG ii 2. 22320 refers to a revival acted by Neoptolemos in 341 of I. A. rather than I.T. A friendly critic reminds me that if the iconographtc tradition is a guide, I.T. far surpassed I.A. in popularity.Google Scholar

47 Haslam, M.W., GRBS 16 (1975), 149–74. Note especially the discussion and parallels adduced in 170 ff. The question of the date of this tampering and its relation to the Alexandrian recension must remain open.Google Scholar

48 N.B. the implications of Plut, . Vir. Oaf. 841Google Scholar f. The latest discussion of the question of interpolation in tragedy, that by Hamilton, R., GRBS 15 (1974), 387–402Google Scholar, is rightly sceptical of the value of statements in the scholia about the activities of actors (cf. Reeve, , GRBS 13 (1972) 249Google Scholar, n.6), but overoptimistic when it comes to dealing with the relationship between fourth-century book-sellers and authors', autographs, (op. cit., p. 391). The arguments of Reeve, , GRBS 14 (1973), 171, satisfy me that it is correct in many instances to speak of ‘actors’, interpolations and that revivals of fifth-century classics had an effect on the transmission of their texts.Google Scholar

49 See Ed. Fraenkel, , SBAW (1963)Google Scholar, Reeve, M.D., GRBS 13 (1972), 451Google Scholar ff., Haslam, M.W., CQ N.S. 26 (1976) 4ff.Google Scholar

50 Line 28 is quoted by Chrysippos (SVF ii.53.26) line 23 exploited by Machon (25 Gow).Google Scholar

51 Fraenkel, (p. 302Google Scholar, n.3) was mistaken in his treatment of the citation in the Rhetoric which might well be the beginning of LA. 80. See Kassel, R., Der Text der aristotelischen Rbetorik (Peripatoi Band 3, Berlin, 1971), pp. 146–7.Google Scholar

52 See Ritchie, , op. cit., p. 2.Google Scholar

53 I do not discuss ![]() For the dangers that arise when they are used in arguments of this sort see Ed. Fraenkel, , Gnomon 37 (1965), 230Google Scholar. One must also acknowledge that many of the oddities in the prologue might be attributable to textual corruption. Caution is needed when dealing with a text as miserably preserved as this one One cannot use the rather jejune phrase

For the dangers that arise when they are used in arguments of this sort see Ed. Fraenkel, , Gnomon 37 (1965), 230Google Scholar. One must also acknowledge that many of the oddities in the prologue might be attributable to textual corruption. Caution is needed when dealing with a text as miserably preserved as this one One cannot use the rather jejune phrase ![]()

![]() in 114 to argue against Euripidean authorship since

in 114 to argue against Euripidean authorship since ![]() seems to be a conjecture intended to complete a line that could no longer be read in its entirety. For a discussion see Zuntz, G., An Inquiry into the Transmission of the plays of Euripides (Cambridge, 1965), pp. 97Google Scholar f., and Barrett's, Hippolytos, p. 249, n.l.Google Scholar

seems to be a conjecture intended to complete a line that could no longer be read in its entirety. For a discussion see Zuntz, G., An Inquiry into the Transmission of the plays of Euripides (Cambridge, 1965), pp. 97Google Scholar f., and Barrett's, Hippolytos, p. 249, n.l.Google Scholar

54 I exclude from consideration the non-Euripidean Rhesos.

55 I am prepared to believe that ![]() in Σ Eur, . Hek. 1 may be an exaggeration.Google Scholar

in Σ Eur, . Hek. 1 may be an exaggeration.Google Scholar

56 See Fraenkel, , 303Google Scholar ff. and Knox, , p. 243Google Scholar, n.19 (for another example of ![]() ) referring to the opening of a play see Σ Eur, . Med. 1). Without the Ravenna scholion on Thesm., however, Nestle's case op. cit., pp. 130 ff. against an anapaestic prologue would be unassailable and one wonders whether the scholion is corrupt or whether there were versions of Andromeda circulating which lacked the original Euripidean trimeter prologue (cf. note 45).Google Scholar

) referring to the opening of a play see Σ Eur, . Med. 1). Without the Ravenna scholion on Thesm., however, Nestle's case op. cit., pp. 130 ff. against an anapaestic prologue would be unassailable and one wonders whether the scholion is corrupt or whether there were versions of Andromeda circulating which lacked the original Euripidean trimeter prologue (cf. note 45).Google Scholar

57 Fraenkel is equivocal in his treatmen of the Andromeda-Echo scene. At one poin it is a ‘duet’, at another a ‘dialogue'. Besides works on Euripides’, fragments Rau, P., Paratragodia (Zetemata 45) (Munich, 1967), 68 ff. is worth consulting for a sensible discussion of the topic and a useful bibliography.Google Scholar

58 Although it is often asserted, it is not the case that Euripides avoided the division of anapaestic dimeters between speakers (as in 16 and 40): note Med. 1397, 1398, Ba. 1372, 1379 (these last two instances in a passage which is probably lyric and is metrically peculiar and textually suspect: see Dodds ad loc). In each case the change of speaker comes at the diaeresis.

58 Soph, . Trach. 977 provides an example of such a division within a paroemiac. Fraenkel in his review of Ritchie argues that the poet of Rhesos was imitating a genuinely Euripidean effect when he wrote Rhesos 15Google Scholar

60 Miss Mellert-Hoffmann's parallels here do not survive scrutiny. See Diggle, , CR N.S. 21 (1971), 179.Google Scholar

61 See Wecklein, , op. cit., p. 728Google Scholar.

62 Dale, A.M., The Lyric Metres of Greek Drama, p. 50Google Scholar (![]() however, ends a paroemiac in Eur, . Ba. 1375Google Scholar – see note 58). Miss Dale also ranks as unique the sequence -uu/ uu-- in 123. This may be removed by accepting the transposition mentioned in Murray's apparatus (it should probably be credited to Herwerden, , RPh N.S. 2 (1878), 47Google Scholar), but there are other examples of this inversion in Euripides and, if we recall that these are lyric anapaests, perhaps the text can stand (see Parker, L.P.E., CQ N.S. 8 (1958), 84).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

however, ends a paroemiac in Eur, . Ba. 1375Google Scholar – see note 58). Miss Dale also ranks as unique the sequence -uu/ uu-- in 123. This may be removed by accepting the transposition mentioned in Murray's apparatus (it should probably be credited to Herwerden, , RPh N.S. 2 (1878), 47Google Scholar), but there are other examples of this inversion in Euripides and, if we recall that these are lyric anapaests, perhaps the text can stand (see Parker, L.P.E., CQ N.S. 8 (1958), 84).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

63 See Page, p. 135. Willink's rewriting here (p. 357) is quite unconvincing.

64 It is not reassuring for those wishing to defend the passage to be told that Xenophon used the word (Page, p. 136).

65 It will hardly do to amend the word to ![]() since these are not lyric anapaests (Willink's tentative

since these are not lyric anapaests (Willink's tentative ![]() in 149 would extend the lyric anapaests in this scene beyond 142. It is quite unacceptable, however, since in the meantime Agamemnon has clearly reverted to non-lyric anapaests). The metrically convenient

in 149 would extend the lyric anapaests in this scene beyond 142. It is quite unacceptable, however, since in the meantime Agamemnon has clearly reverted to non-lyric anapaests). The metrically convenient ![]() is used in another anapaestic passage in this play (1282). Elsewhere in tragedy it occurs only in lyric.

is used in another anapaestic passage in this play (1282). Elsewhere in tragedy it occurs only in lyric.

66 I would take it as ‘completely’, rather :han ‘up to the end’.

67 Der Monolog in Drama (Abh.Gött. Ges.d.Wiss.Phil.-hist.Klasse n.f. x.5) (Berlin, 1908), p. 25.Google Scholar

68 Friedrich, (p. 91Google Scholar, n.2.) and Knox, (p. 255) use it to argue that the anapaests and :rimeters are complementary.Google Scholar

69 This point is stressed by Hermann, , Opuscula 8.24.Google Scholar

70 Fr. 558N

71 See Page, Creek Literary Papyri, no. 16. Of course this prologue is lacunose. Wilamowitz wanted the mention of the name o come after line 6 (CPh i (1908), 227Google Scholar, n.2. = Kleine Schriften i. 276Google Scholar, n.2.). On the analogy of the Hkld. prologue it could come just as well after 13 in the speech of the ![]() which Bellerophon reports. See also Zühlke, B., Philologus 105 (1961), 201CrossRefGoogle Scholar who suggests that the name came after 27. I am not convinced by the arguments of Hourmouziades, N.C., Production and Imagination in Euripides (Athens, 1965), p. 153.Google Scholar

which Bellerophon reports. See also Zühlke, B., Philologus 105 (1961), 201CrossRefGoogle Scholar who suggests that the name came after 27. I am not convinced by the arguments of Hourmouziades, N.C., Production and Imagination in Euripides (Athens, 1965), p. 153.Google Scholar

72 Contra Leo, I think it improbable that anything is missing before the opening line of the trimeters. It looks like the opening of a Euripidean play (cf. I. T. 1 ff.). If one were to suggest a place for the name, it might be worth guessing that the corrupt line 84 is the product of a join after the passage had been lost in which Agamemnon had let his name slip.

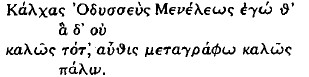

73 Markland suggested ![]() in 105. Vitelli elegantly rewrote 107 f.:

in 105. Vitelli elegantly rewrote 107 f.:

See Jackson, John, Marginalia Scaenica, p. 209 (Murray's error in reporting Vitelli probably stems from using the report of his conjecture in England's apparatus).Google Scholar

74 So Willink who follows Herwerden in deleting 105 and treating 106 as a parenthesis. It is hard to have to wait so long for a subject for ![]() and even harder in this context to take

and even harder in this context to take ![]() as third person.

as third person.

75 So Knox, , p. 255.Google Scholar

76 As Fraenkel says: ‘von einer solchen sinnvollen Motivierung as I. T. 760 ff. und I.A.. 117 ff. ist aber an den entsprechenden Stelle des Trimeterprologs 112 f., nicht das geringste zuspüren.'

77 Knox's statement ‘no motive is stated but one leaps to mind’, (256) condemns itself.

78 Apart from grounds of palaeographical probability ('I have adopted both Clement's readings, the former on its merits, the latter because the change from ![]() is much more likely to have been made by inadvertence than the opposite change’, England) 1 do not know what it is that makes editors prefer the reading

is much more likely to have been made by inadvertence than the opposite change’, England) 1 do not know what it is that makes editors prefer the reading ![]() found in Clement (Clem, . Al. Paed. iii.2Google ScholarStählin, i. p.243Google Scholar) to

found in Clement (Clem, . Al. Paed. iii.2Google ScholarStählin, i. p.243Google Scholar) to ![]() Why should the Argives allege that Paris judged (or was a habitual judge of) divine beauty contests? If anything it should be

Why should the Argives allege that Paris judged (or was a habitual judge of) divine beauty contests? If anything it should be ![]()

![]() as people say’, ‘as is said’, is protected by

as people say’, ‘as is said’, is protected by ![]() Cratinus fr. 228 Kock,

Cratinus fr. 228 Kock, ![]() Theocritus 15.107,

Theocritus 15.107, ![]() Soph. Ant. 829,

Soph. Ant. 829, ![]() Archilochos fr. 174 West,

Archilochos fr. 174 West, ![]()

![]() Eur, . Ion 265Google Scholar (cf. also

Eur, . Ion 265Google Scholar (cf. also ![]()

![]()

![]() Eur, . Ba. 295).Google Scholar

Eur, . Ba. 295).Google Scholar

79 See Lloyd-Jones, H., CR N.S. 15 (1965), 242.Google Scholar

80 As e.g. at Soph, . El. 301Google Scholar and Soph, . O.T. 1452Google Scholar. See Kühner-Gerth, 2.645Google Scholar and Dover, , Aristophanes Clouds, p. 104.Google Scholar

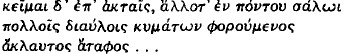

81 Fraenkel calls it ‘vollig gegen den Stil einer euripideischen Prologerzählung'. Perhaps the nearest analogy would be found in the pathetic way in which Polydorus’, ghost (Eur, . Hek. 28 ff.) draws attention to his fate: Google Scholar

Google Scholar

82 I am not sure that we can decide whether we have two people at work in the composition of them, the composer of an alternative trimeter prologue and a man whc composed 105 ff. as a link with the anapaests, or whether all the trimeters are attributable to a single interpolator.

83 For other problems in the anapaests see Page, pp. 131–6. I feel some misgivings about 141–63 and suspect they may have been a later edition. The old man is told to be on his way in 140 and indicates that he is leaving σφεὐδω, βασιλεδ yet he is rather pointlessly detained while Agamemnon gives him further hypothetical instructions. As well as the feeble gnome 161 ff. the passage contains a description of dawn in 156 ff. whose close resemblance to Ion 82 ff. may not be accidental.

84 So Diggle, , CR N.S. 21 (1971), 180.Google Scholar Webster, op. cit., argues that the degree of resolution in the trimeters supports Euripidean authorship (on my count there are only 16 resolved longa in 65 lines as against 26 in 63 lines of the prologue of the contemporaneously produced Bakchai – more significant, however, might be the presence of ξυναμυνεἰν before the penthemimeral caesura in 62 on which see Zieliński, , op. cit., p. 195Google Scholar, and Dale's, Helen commentary, p. xxvii.Google Scholar). This is not conclusive since, although some later tragedians, e.g. the author of Rhesos, Moschion, and the Pleiad attempted to go against the Euripidean tide of resolution, there are plenty of fourth-century dramatists who show the same tendencies as Euripides (see CF. Müller, , De pedibus solutis in tragicorum minorum trimetris iambicis (Kiel, 1879), 20Google Scholar f. and Collard, C., JHS 90 (1970), 30).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

85 The suggestion that Euripides wrote another prologue which has since disappeared need not detain us here. The lines quoted by Aelian do not come from a prologue (see Page, p. 200) and if genuine they must have formed part of an alternative exodos. As they stand they are either non-Euripidean or corrupt. It remains a possibility that Euripides did not intend there to be a scene between Agamemnon and the old man before the parodos. We do not need to have seen the old man to make sense of his entrance at 303 ff. If we had been told about him and the letter he was carrying, there is no problem, the situation becoming completely clear by 314 f.