Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

It has commonly been assumed that, on ancient Greek instruments of the lyre-type (lyre, barbitos, cithara), when a string had been tuned to a certain note, that note and that note only could be played, until the string was retuned; thus, that a separate string was required for each note of a given scale. This (which may be called the orthodox) view involves certain difficulties. The canonical number of strings was seven, and seven-stringed lyres and citharas continue to be represented in art throughout the classical period. But, with one note to each string, a seven-stringed lyre could not even play a complete diatonic octave.

page 169 note 2 Arist. Probl. 19. 12 refers to  by which is clearly meant the application of pressure to the central point of a string: the note sounded on either side of this point will be an octave higher than the note of the undivided string. It is not, however, clear whether the writer envisages a practical technique or an experiment upon the monochord. Athenaeus, 14. 638 a (on Lysander of Sikyon) may possibly be referring to such a technique, but the interpretation is doubtful. For a method other than stopping of raising the pitch of a string without retuning see p. 184.

by which is clearly meant the application of pressure to the central point of a string: the note sounded on either side of this point will be an octave higher than the note of the undivided string. It is not, however, clear whether the writer envisages a practical technique or an experiment upon the monochord. Athenaeus, 14. 638 a (on Lysander of Sikyon) may possibly be referring to such a technique, but the interpretation is doubtful. For a method other than stopping of raising the pitch of a string without retuning see p. 184.

page 169 note 3 ‘Die griechische Instrumentalnoten-schrift’ (Zeitschrift f. Musikwissenschqft, vi [1924], 289–301).Google Scholar Cf. ‘Die griechische Gesangsnotenschrift’ (ibid, vii [1925], 1–5); History of Musical Instruments, pp. 131–5;Google ScholarRise of Music in tile Ancient World, pp. 203–5.Google Scholar

page 170 note 1 For the sake of simplicity, I employ only capital letters for the notes of the scale. As we shall be dealing with the central octave only, no confusion, I trust, arises. I read the scales upwards, since I think most people find this easier to follow. In doing so I imply nothing about the theoretical structure of the scales or the tendencies of Greek melody.

page 170 note 2 For the purposes of this article it is per haps unnecessary to draw the distinction between  and

and  which some contexts demand. Only that portion of each

which some contexts demand. Only that portion of each  will come under consideration which lies in the central range of the voice.

will come under consideration which lies in the central range of the voice.

page 170 note 3 Pauly-Wissowa, xiii. ii, col. 2485 (s.v. Lyra). The paragraph in question has all the appearance of a hasty afterthought: Quintilian 12. 10. 68 (11. 273 Teubner) is quoted as Aristid. Quintil. 11. 273; by Plutarch de mens. 16 a reference to the de musica (on Phrynis) is intended. The wrong chapter reference and ‘Aristides’ both derive from Sachs's article.

page 170 note 4 P.-W. xvi. i, col. 851 (s.v. Musik).

page 170 note 5 Ptolemaios und Porphyrios über die Musik, p. 219 n. 5;Google Scholar‘Studies in Musical Terminology in Fifth Century Literature’ (Eranos xliii [1945]. 176–97. esp. 192 ff.).Google Scholar

page 171 note 1 Deubner, L., ‘Die viersaitige Leier’ (Athen. Mitteihmgen, liv [1929], 194–200).Google Scholar

page 171 note 2 Notably the evidence of Plutarch, mus. ch. 11 (§§ 104ff. W.-R.) and ch. 19 (§§ 172 ff.), on the spondeion. Cf. Class. Quart. xxii. 2 (1928), 83 ff.Google Scholar The ‘defective’ spondeion with its compass of a minor sixth argues for the genuineness of the ‘defective’ scales in Aristides Quintilianus, 1, ch. 9 (13. 12 ff. Jahn): the Ionian with its compass of a seventh, the syntonon Lydian with its compass of a minor sixth. Other grounds for believing the scales of Aristides to be genuinely ancient are given by Mountford, J. F. in Class. Quart. xvii (1923), 126 ff.Google Scholar

page 171 note 3 Book 19 of the Aristotelian Problems gives a disappointing yield. There is the difficulty whether, in any particular case,  means ‘string’ or (as it admittedly came to mean) ‘note’. In 18, which refers to singing, it must mean ‘note’. Only 20 and 36 refer directly to tuning. In 20

means ‘string’ or (as it admittedly came to mean) ‘note’. In 18, which refers to singing, it must mean ‘note’. Only 20 and 36 refer directly to tuning. In 20  (89. 5 Jan) must mean strings, but only mese and lichanos are specified. In 12 Monro restored

(89. 5 Jan) must mean strings, but only mese and lichanos are specified. In 12 Monro restored  and

and  with great plausibility, in which case the reference is to the playing of strings, but the only strings mentioned are mese, paramese (or paranete), nete and hypate. All these strings existed on the pentatonic hypothesis. The other relevant Problems can all be interpreted in terms of notes of the scale rather than strings of the lyre.

with great plausibility, in which case the reference is to the playing of strings, but the only strings mentioned are mese, paramese (or paranete), nete and hypate. All these strings existed on the pentatonic hypothesis. The other relevant Problems can all be interpreted in terms of notes of the scale rather than strings of the lyre.

page 171 note 4 One might suppose that Phrynis, to demonstrate his virtuosity, took a five-stringed lyre and played on it in a multiplicity of harmoniai. But this would be a special and unsupported hypothesis designed solely to explain this one debatable text. Sachs and During (article in Eranos—see p. 170, n. 5) suggest that he used a mechanical device of his own invention  for this purpose. But this interpretation of the text is highly speculative.

for this purpose. But this interpretation of the text is highly speculative.

page 172 note 1 Cf. R. G. Austin's note (following Mountford) in his edition of Quintilian 12. The principle seems right, though the details are obscure.

page 172 note 1 Gombosi, (Tonarten, pp. 20 f.)Google Scholar also invokes Plutarch, mus. ch. 39 (§ 406 W.-R.). It by no means follows, however, that, because tritai and parhypatai were flattened ‘in addition to’ or ‘in the direction of’ (the two possible senses of  in

in  ) the standing-notes, they were produced from the same strings as the latter. Indeed, on the hypothesis, they were ‘pien-tones’ (v. infra) and their intonation was thus completely under the control of the player.

) the standing-notes, they were produced from the same strings as the latter. Indeed, on the hypothesis, they were ‘pien-tones’ (v. infra) and their intonation was thus completely under the control of the player.

page 172 note 3 Dorian: EfGABcDE. Hypodorian: Ef#GABc#DE. Phrygian: Ef#GABc#DE. (Lower-case letters are used for notes obtained by stopping.)

page 172 note 4

page 172 note 5

page 172 note 6 Rep. 349 e

Rep. 591 d; Phaed. 85 e ff.; Theaet. 144 c.

Rep. 591 d; Phaed. 85 e ff.; Theaet. 144 c.

page 172 note 7 In Stesichorus (25 b Diehl = Simonides 46 Bergck)  of the aulos is more probably a conscious metaphor than a ‘faded’ use. So too in this Platonic context, though in this case it might be a refurbishing of a use already faded.

of the aulos is more probably a conscious metaphor than a ‘faded’ use. So too in this Platonic context, though in this case it might be a refurbishing of a use already faded.

page 173 note 1 Plato here disregards the increase in the number of strings on the cithara, which may have been subsequent to the dramatic date of the Republic, and which in any case fell short of the  of, for example, the magadis. Essentially the same point is made by Aristides Quintilianus, 2. 18 (65. 19 ff. Jahn), where he contrasts stringed and wind instruments: the former are

of, for example, the magadis. Essentially the same point is made by Aristides Quintilianus, 2. 18 (65. 19 ff. Jahn), where he contrasts stringed and wind instruments: the former are  the latter is

the latter is

i.e. ‘suited to rapid modulation’.

i.e. ‘suited to rapid modulation’.

page 173 note 2

page 173 note 3 Pythagoras of Zacynthus is mentioned as a theorist by Aristoxenus, 2. 36 (127. 24 Macran). I know of no other evidence by which he can be dated. Artemon, of Cassandreia, is probably of the second or first century B.C.

page 173 note 4 Sachs quotes (iii) and (iv) without, ap-parendy, perceiving their bearing upon his own theory.

page 174 note 1 No convincing theory of the origin of these forms has yet been advanced.

page 174 note 2 There are some exceptions, which, though they may have a bearing on the history of the notation, need not be discussed here.

page 174 note 3 Cf. Gombosi, , Tonarten, p. 21, n. 1.Google Scholar

page 174 note 4 The notation of this series will be found in Grove's, Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 5th edition, iii. 779;Google Scholar of all the triads in Gombosi, , Tonarten, p. 20.Google Scholar There are complete tables in Gevaert, , Histoire et théorie de la musique de l'antiquité, i. 408–15, and in other comprehensive works.Google Scholar

page 174 note 5 See, however, p. 176.

page 174 note 6 I have been much helped here by Gom bosi' sfull and lucid exposition.

page 175 note 1 i.e. the central range of pitch, containing the notes hypate meson to nete diezeugmenon according to the thetic nomenclature.

page 175 note 2 In the Hypolydian and Lydian, though the central octave extends from F to F, the F's are, according to the hypothesis, obtained from strings tuned to E. The Hypolydian, which requires a B, is in fact tuned (ex hypothesi): E G A B D E.

page 175 note 3 Convenient terms of Greek theory

for indicating the lowest, the middle, and the highest notes of an enharmonic or chromatic pycnon.

for indicating the lowest, the middle, and the highest notes of an enharmonic or chromatic pycnon.

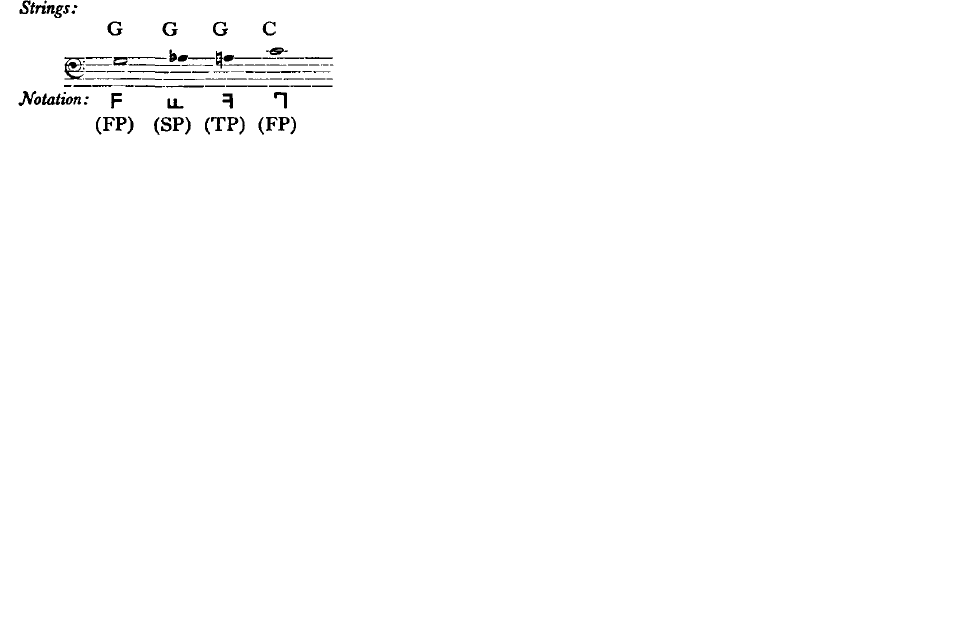

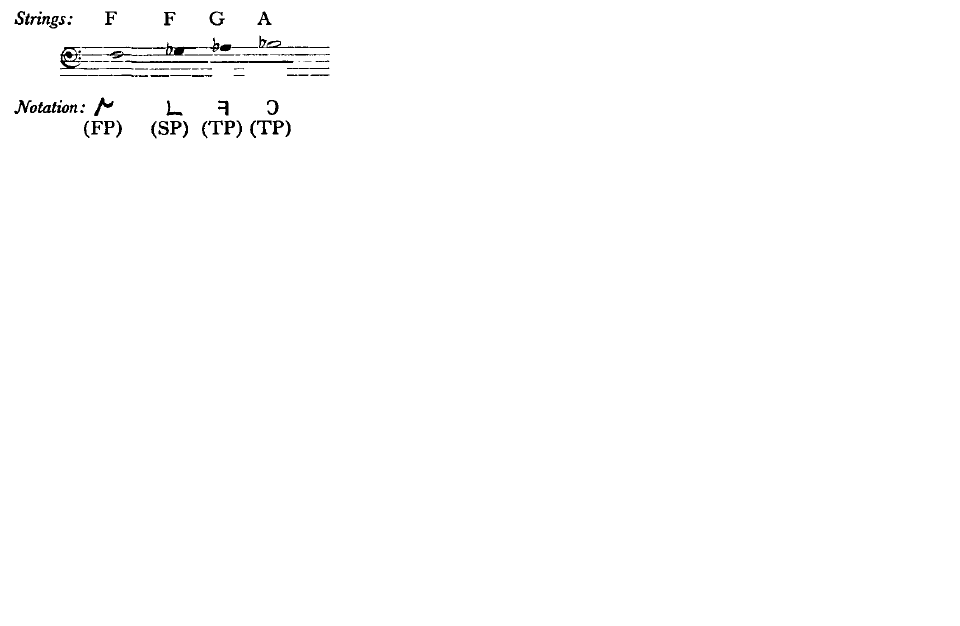

page 175 note 4 e.g. the tetrachord meson of the Phrygian tonos in the chromatic genus:

page 175 note 5 It is not open to adherents of the hypothesis to argue that the notation was different because the two notes were not in fact identical: for them the notation is concerned with strings and fingering, not with subtleties of intonation.

page 175 note 6 The terms parhypatoeidē  and lichanoeidē

and lichanoeidē  are convenient for indicating the notes which come, respectively, second and third in the standard tetrachord (reading upward). The former includes both parhypatai and tritai, the latter both lichanoi and paranetai.

are convenient for indicating the notes which come, respectively, second and third in the standard tetrachord (reading upward). The former includes both parhypatai and tritai, the latter both lichanoi and paranetai.

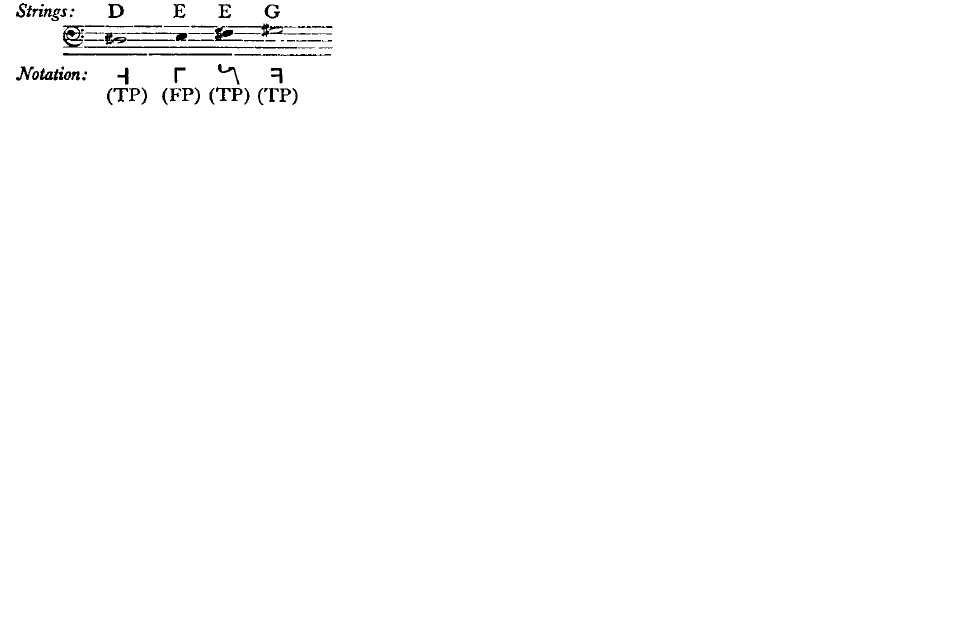

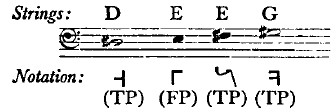

page 175 note 7 e.g. the tetrachord meson of the Dorian tonos in the diatonic genus:

page 176 note 1 It is not adequate to say that the middle finger (Sachs: index finger) was already engaged in stopping the string of lower pitch. This, if true, was only true when the two notes occurred consecutively in the melody.

page 176 note 2 The open C string is used in the Dorian, the open F string in the Hyperdorian, for paramese.

page 176 note 3 According to Gombosi the Hypolydian and Lydian had a double function: the former served both as a ‘high’ Hypolydian and as a ‘low’ Dorian, the latter both as a ‘high’ Lydian and as a ‘low’ Mixolydian. There is much to be said for this view, which is perhaps confirmed by the recently published Oslo papyrus (cf. Symb. Osl. xxxi [1955], 54.Google Scholar

He also assumes a ‘low’ Hypodorian, below the fifteen tonoi of Alypius, of which the Hyperionian would be a duplicate at the octave. There are no grounds, however, for supposing that the theoretical system ever embraced such a tonos: the assumption that Ptolemy conceived his tonoi in ‘low tuning’ is unfounded (see also p. 182, n. 3).

page 177 note 1 e.g. the tetrachord meson of the Aeolian tonos in the chromatic genus:

page 177 note 2 The exceptional tetrachords are: Ionian synemmenon, Hyperionian meson, synemmenon, and hyperbolaion (see p. 180).

page 177 note 3 Again, it is not open to adherents of the hypothesis to say that the A# and the Bb differed in pitch and were therefore noted differently (see P. 175, n.5). On the hypothesis, both notes were ‘pien-tones’ (v. infra) and their intonation under the full control of the player.

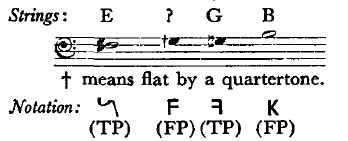

page 177 note 4 e.g. the tetrachord meson of the Ionian tonos in the enharmonic genus:

The F# is played (ex hypothesi) on the E string. On the question why a symbol of the F traid is used see p. 178 below).

page 177 note 5 See, however, pp. 182 f. for adjustments to the basic tuning which in some cases the hypothesis seems to require—though not on so extensive a scale.

page 177 note 6 Gombosi unwisely seeks to support this conclusion by reference to the tables in Alypius, for which the Ionian and Hyperionian enharmonic are absent. They are absent because they fall in a large lacuna, coming at the end of the treatise, beginning half-way through the Hyperphrygian enharmonic, and involving the entire Ionian and Dorian groups. There is no reason whatever to suppose that the original was incomplete. The missing diagram in Arist. Quint. I, ch. II (16. 30 J.) clearly gave the notation of all fifteen tonioi in all three genera.

page 178 note 1 The Hyperaeolian exhibits the same phenomenon an octave higher.

page 178 note 2 e.g. the tetrachord meson of the Hypoaeolian tonos in the diatonic genus:

The E-string triad is  the F-string triad is

the F-string triad is  See also the illustration in p. 177, n. 4.

See also the illustration in p. 177, n. 4.

page 178 note 3 When Gombosi finds the same combination used to note  in the Hyperdorian, he postulates (Tonarten, p. 48) the use of both alternative strings. But is there any more reason for postulating it there than for

in the Hyperdorian, he postulates (Tonarten, p. 48) the use of both alternative strings. But is there any more reason for postulating it there than for  in the Aeolian and Ionian (etc.) ? Sachs, (Rise of Music, p. 204)Google Scholar suggests that the reason for employing a C symbol was ‘probably to avoid a chromatic interpretation’: the reason seems hardly adequate.

in the Aeolian and Ionian (etc.) ? Sachs, (Rise of Music, p. 204)Google Scholar suggests that the reason for employing a C symbol was ‘probably to avoid a chromatic interpretation’: the reason seems hardly adequate.

page 178 note 4 i.e. the tonoi listed on p. 175 (disregarding the duplicates): the intervals of the octave-species are found in these tonoi between F and F. It has generally been supposed that these tonoi were earlier than the intervening tonoi of the Ionian-Aeolian group. Gombosi, who believes that they were later, has to assume that the names originally borne by the ‘low’ tonoi were transferred at some stage to the ‘high’ tonoi, which were then renamed Ionian, Aeolian, etc. But, quite apart from the question of nomenclature, it is surely more probable that those tonoi whose notation is well adapted to the enharmonic genus are earlier than those whose notation is not.

page 179 note 1 Cf. Oxford Classical Dictionary, s.v. ‘Music’, 590, col. i. One can only speculate on the number and range of the tonoi for which die notation was originally designed, but Aristoxenus (see p. 180, n. 3) is evidence that the number of tonoi recognized was at first small.Google Scholar

page 179 note 2 And thus failed to provide a continuous series of quarter-tones—except where the semitones occur in the basic series.

page 179 note 3 Cf. Class. Quart. xxvi (1932), 195–208, esp. 202 f., 206 f. To what I have said there I will only add that Archytas' is the only mathematical evaluation of the enharmonic which dates from a period when the en harmonic was certainly alive.Google Scholar

page 179 note 4 Taking the illustration in p. 175, n. 4, the interval between FP and TP is a tone in the chromatic, but only a semitone in the enharmonic.

page 179 note 5 See n. 2 above.

page 180 note 1 See p. 178, n. 4.

page 180 note 2 Another anomalous effect of the scheme is that TP symbols occur as oxypycna in consecutive tonoi; for instance,  represents chromatic and enharmonic lichanos meson in both Aeolian and Lydian. If the symbol is given a chromatic value in the Aeolian and an enharmonic value in the Lydian, the equation is correct.

represents chromatic and enharmonic lichanos meson in both Aeolian and Lydian. If the symbol is given a chromatic value in the Aeolian and an enharmonic value in the Lydian, the equation is correct.

page 180 note 3 This is an additional reason for sup posing that it was at first designed for a comparatively small number of tonoi. The fact that anomalies occur in the Mixolydian/Hyperdorian may suggest that this tonos was not embraced in the original scheme. It may, therefore, be significant that the predecessors of Aristoxenus (Harm. 128. 6–23 Macran) were not agreed about the position of the Mixolydian tonos.

page 180 note 4 Sachs, , Rise of Music in the Ancient World, p. 229.Google ScholarCf. Reese, , op. cit., p. 25.Google Scholar

page 181 note 1 ‘In lyre or kithara music, the fact that a tone produced by a stopped string would, in the absence of a fingerboard, be more muffled than a tone produced by an open string, may have had an effect on ethos’ (Reese, , op. cit., p. 45Google Scholar). Cf. Gombosi, , Tonarten, p. 142.Google Scholar

page 181 note 2 The Phrygian was especially associated with the aulos, but Plato in the Laches (see p. 172, n. 5) implies that a lyre might be tuned to the Phrygian harmonia. Pindar also provides evidence: compare Ol. 5. 21 with Nem. 4. 44 f., and Nem. 3. 79 with Pyth. 2.69. Ptolemy seems to imply that the lyre-players employed all the seven tonoi of his theoretical system.Google Scholar

page 181 note 3 The evidence is examined in my Mode in Ancient Greek Music. See also Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 5th edition, iii. 774–9.Google Scholar

page 181 note 4 Papers read at the International Congress of Musicology, published by the Music Educators' National Conference for the American Musicological Society,New York,1939, p. 181.Google Scholar

page 182 note 1 See p. 176, n. 3.

page 182 note 2 Gombosi, , Tonarten, p. 27, suggests that the ‘high’ tuning came to be preferred because of ‘der schärfere, hellere und stärkere Klang der angespannteren Saite’. But in the ‘high’ Dorian only three notes out of eight are on open strings and only these could have possessed a stronger tone.Google Scholar

page 182 note 3 Cf. Gombosi, , Tonarten, 108 ff. On this assumption the evidence of Ptolemy can be brought into relation with that of Porphyry and Bellermann's Anonymus. Gombosi argues convincingly on this point. It is not correct, however, to suppose that Ptolemy, in his theoretical system, conceived his tonoi as ‘low’ tonoi. Rather, he regarded such a distinction as irrelevant. Gombosi's argument (op. cit. 99) is based on a misunderstanding of Ptolemy H., ch. 11 (65. 24 ff. D.).Google Scholar

page 182 note 4 But not the G string in Iastiaiolia.

page 182 note 5 In the Hypodorian, for instance, the lower of the two standard tetrachords runs from F#f to B. If G-A is fixed at 9/8, the inintonation will inevitably be that of the ‘ditonal’ diatonic. To obtain the ‘tonal’ diatonic, the G string must be lowered in pitch.

page 182 note 6 The correct nomenclature is given at 80. 18 D. At 39. 14, where the MSS. have

I suspect that we should read

I suspect that we should read

page 183 note 1 Gombosi (103, 105) calb attention to these ratios.

page 183 note 2 As implied by Porphyry, ad H. 126. 10 ff. D. (one of our rare pieces of direct evidence about tuning).

page 183 note 3 The false fourth and false fifth which the tuning involves occur between open strings.

page 183 note 4 Gombosi, , Tonarten, 48 ff., 121 f.Google Scholar, and Wegner, M., Das Musikleben der Griechen, furnish valuable catalogues of vase-paintings and other monuments containing representations of lyre-type instruments.Google Scholar

page 183 note 5 Whether or not the fingers of the left hand ever damped strings (as has been suggested), they certainly also plucked them.

page 183 note 6 The passages relating to the Aspendius citharista (Cicero, II Verr. 1. 53; the scholiast ad loc.; the proverb in Zenobius 2. 30 and Plutarch, paroem. 120) are not so informa tive as we could wish, but imply that it was a tour deforce to dispense entirely with the right hand.Google Scholar

page 184 note 1 The citharist, for instance, on the Munich crater (3268—Wegner, pl. 22) is tuning the instrument? But see p. 186, n. 1.

page 184 note 2 Cf. Gombosi, , Tonarten, p. 119, and pp. 179 ff.Google Scholar of the paper referred to on p. 184, n. 4; Wegner, , Musikleben, p. 33.Google Scholar This is very clearly shown, for the cithara, on the London hydria (B 300—Wegner, pl. 8); for the lyre, on the Berlin Duris cup (Pfuhl, , Masterpieces, no. 65).Google Scholar

page 184 note 3 In order to raise the pitch by a major tone, the string length must be decreased by a ninth, and I do not see how in fact the cross-bar could be effectively used in this operation. But on these technical matters the non-expert hesitates to speak. It seems highly probable that, if strings were in fact stopped without a fingerboard, the tone would at least be very poor: the poorer the tone, the more weight attaches to the objections raised in Section V.

page 185 note 1 Cf., e.g., Hom. Hymn to Apollo, 184 f.; Pindar, Nem. 5. 24; Eur. Her. 350.

page 185 note 2 The Japanese have technical terms for single and double pressure.

page 185 note 3 As noted on p. 177, there seems to be an exception to this rule.

page 185 note 4 I am not quite sure what Gombosi implies when he says (Tonarten, p. 120Google Scholar): ‘wenn das Plektron über zwei Saiten quergelegt werden muβte’.

page 185 note 5 Philostratus minor, Imag. 6 (400. 25 Kayser).

page 185 note 6 It is not clear that the technique would be any more appropriate to the use of the fingers without plectrum. In any case the use of the plectrum was normal from a period which must long antedate the notation.

page 186 note 1 Cf. Behn, F., Musikleben im Altertum und frühen Mittelalter, p. 89. Since writing this article, I have seen a RF cup in Mykonos Museum (KZ 1402), representing a player with his left hand on the strings and his right hand on the cross-bar, as on the Munich crater (see p. 184, n. 1). The fact that his mouth is open suggests that he is playing rather than tuning his instrument.Google Scholar