Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

No satisfactory treatment of the whole subject of jurisdiction in the Athenian Empire of the fifth century B.C. yet exists, and in this paper I make no attempt to provide a complete account. My purpose is twofold: to deal in some detail with certain specific problems, and to demonstrate that the most fruitful method of approach to the whole subject—perhaps, indeed, the only one which can reduce it to order–is to divide it up under three particular headings and to treat each of these separately. Only Part I will be included in the present issue of this journal; Parts II and III, with a brief Conclusion, will appear in a later issue.

page 94 note 2 The only recent work which attempts to give a complete account, namely Robertson, H. G., The Administration of Justice in the Athenian Empire (1924), is very unsatisfactory.Google Scholar

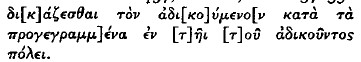

page 94 note 3 This seems clear, if only from Ar. fr. 278 (Kock, , C.A.F. i. 463)Google Scholar. It appears from the new restoration of the last four lines of Face A of I.G. i 2. 6Google Scholar (with I.G. i 2. 9)Google Scholar by Meritt, B. D., in Hesp. xv (1946), 249–51, that there might be![]() the parties to which were

the parties to which were![]() collectively and another state.Google Scholar

collectively and another state.Google Scholar

page 94 note 4 All our evidence, as far as I know, is from the period of the full![]() (see n. 2 on p. 107 below). Undoubtedly, in the early years of the Delian League, the League

(see n. 2 on p. 107 below). Undoubtedly, in the early years of the Delian League, the League![]() sometimes acted in a judicial or quasi-judicial capacity. That the reduction of allies who had ‘revolted’ was on some occasions at any rate (probably on all occasions in the early days of the League) authorized by a formal vote of

sometimes acted in a judicial or quasi-judicial capacity. That the reduction of allies who had ‘revolted’ was on some occasions at any rate (probably on all occasions in the early days of the League) authorized by a formal vote of![]() is certain, if only from Thuc. 3. 10. 5 (

is certain, if only from Thuc. 3. 10. 5 (![]() ); 3. 11. 4

); 3. 11. 4![]() cf. 1. 97. 1 Jones, A. H. M., in Proc. Camb. Philol. Soc. (1952/1953), 43–46, suggests that this procedure was adopted as late as 440, on the revolt of Samos. Did the

cf. 1. 97. 1 Jones, A. H. M., in Proc. Camb. Philol. Soc. (1952/1953), 43–46, suggests that this procedure was adopted as late as 440, on the revolt of Samos. Did the![]() in these earlier years, perhaps also try offences against those League regulations which it had itself authorized ? The whole subject of the activities of the

in these earlier years, perhaps also try offences against those League regulations which it had itself authorized ? The whole subject of the activities of the![]() , however, is very obscure, and I think we can ignore it for present purposes. All the cases I have in mind in Part II would have been tried at Athens, by a purely Athenian jury or the Athenian assembly itself; and under the full

, however, is very obscure, and I think we can ignore it for present purposes. All the cases I have in mind in Part II would have been tried at Athens, by a purely Athenian jury or the Athenian assembly itself; and under the full![]() I doubt if the Athenians ever troubled to get such a decision rubber-stamped, so to speak, by a League

I doubt if the Athenians ever troubled to get such a decision rubber-stamped, so to speak, by a League![]() .Google Scholar

.Google Scholar

page 95 note 1 Thuc. 3. 70. 3 ff.

page 95 note 2 The treaties are![]() in the fifth century sources. In the fourth century sometimes, and later always, they are

in the fifth century sources. In the fourth century sometimes, and later always, they are![]() In either case we normally find the plural used also for die singular, as with

In either case we normally find the plural used also for die singular, as with![]()

page 96 note 1 See Pringsheim, F., The Greek Law of Sale (1950), esp. pp. 90–92Google Scholar; Gernet, L., Droit et socélté dans la Gréce ancienne (1955), pp. 201–36Google Scholar; and, for a brief outline, Jones, J. W., The Law and Legal Theory of the Greeks (1956), pp. 227–31Google Scholar. Actions (![]() , perhaps, although the expression does not occur in the surviving sources) might arise after the sale of slaves (Hyper, , c. Athenog. 15Google Scholar) and conceivably of certain animals (but see Pringsheim, , op. cit., pp. 477–80Google Scholar, 487–8), if the purchaser found some latent defect: these, at Athens, will have been among the

, perhaps, although the expression does not occur in the surviving sources) might arise after the sale of slaves (Hyper, , c. Athenog. 15Google Scholar) and conceivably of certain animals (but see Pringsheim, , op. cit., pp. 477–80Google Scholar, 487–8), if the purchaser found some latent defect: these, at Athens, will have been among the![]() (and perhaps

(and perhaps![]() ) of Arist., Ath. Pol. 52. 2.Google Scholar

) of Arist., Ath. Pol. 52. 2.Google Scholar

page 96 note 2 Goodwin, W. W., in A.J.P. i (1880), 4. The article is not a helpful one.Google Scholar

page 96 note 3 Gomme, A. W., Hist. Comm. on Thuc. i. 236–43.Google Scholar

page 96 note 4 I say ‘virtually all’ because of the possibility that some states, for a time anyway, may not actually have had![]() with Athens, and yet that litigation may have taken place between their citizens and Athenians; cf. Ps.-Dem. 7. 9–13, discussed in Appendix C below.

with Athens, and yet that litigation may have taken place between their citizens and Athenians; cf. Ps.-Dem. 7. 9–13, discussed in Appendix C below.

page 96 note 5 It will be obvious to anyone who knows the extensive literature that I am ignoring certain variants which seem to me not to deserve detailed discussion: for example, the view ultimately adopted by Gomme (p. 243, with 236), according to which Thucydides' first participial clause refers to![]() conducted in allied courts, and his second

conducted in allied courts, and his second![]() to ‘other classes of

to ‘other classes of![]() which are tried at Athens (namely, political trials)’. Quite apart from the unfortunate use of the expression, ‘political trials’ (on which see p. 95 above), this rendering misses the contrast between the unfairness of the allied courts and the fairness of the Athenian ones, and makes nonsense of both participial clauses, the first because it becomes totally irrelevant to the charge of philodikia (as indeed Gomme himself appears to admit, on p. 243), and the second because it is now open, mutatis mutandis, to the objections set out on pp. 97–98 below to what I have called ‘interpretation A’. See also Turner's article, cited in p. 97, n. 3 below.

which are tried at Athens (namely, political trials)’. Quite apart from the unfortunate use of the expression, ‘political trials’ (on which see p. 95 above), this rendering misses the contrast between the unfairness of the allied courts and the fairness of the Athenian ones, and makes nonsense of both participial clauses, the first because it becomes totally irrelevant to the charge of philodikia (as indeed Gomme himself appears to admit, on p. 243), and the second because it is now open, mutatis mutandis, to the objections set out on pp. 97–98 below to what I have called ‘interpretation A’. See also Turner's article, cited in p. 97, n. 3 below.

page 97 note 1 In particular, cf. I. 77. 3–4. with 4. 86.6.

page 97 note 2 Secs. 5–6 of chap. 77 can be ignored here, as introducing side issues only—not to mention an element of confusion, in![]()

![]() for which see Steup and Gomme ad. loc.

for which see Steup and Gomme ad. loc.

page 97 note 3 ‘![]() (Thuc. I. 77)’, in C.R. lx (1946), 5–7.Google Scholar

(Thuc. I. 77)’, in C.R. lx (1946), 5–7.Google Scholar

page 99 note 1 After this paper was finished, I received a letter from Prof. Wade-Gery (then in the U.S.A.) containing an entirely new interpretation of Thuc. i. 77. 1, to which, with Wade-Gery's kind permission, I have referred in an Addendum on pp. 111–12 below.

page 99 note 2 This, I think, is the force of![]() See Denniston, J. D., The Greek Particles, pp. 110–11.Google Scholar

See Denniston, J. D., The Greek Particles, pp. 110–11.Google Scholar

page 100 note 1 I.G. i2. 16 = Tod, i2. 32. The best text is that given, with a translation and commentary, by Wade-Gery, H. T., Essays in Greek History (1958), pp. 180–200. On the question of the date, see esp. pp. 184–5, 189, 192–7.Google Scholar

page 100 note 2 See Arist, . Ath. Pol. 59. 6.Google Scholar

page 100 note 3 Needless to say, when I speak of ‘the courts of the Thesmothetai’ or ‘the Polemarch's court’, I mean no more (in relation to the period after c. 462/1 at any rate) than the heliastic courts![]() presided over by one of the Thesmothetai, or the Polemarch. It is very likely that before c. 462/1 the presiding magistrate had considerable powers, and was a judge rather than a mere

presided over by one of the Thesmothetai, or the Polemarch. It is very likely that before c. 462/1 the presiding magistrate had considerable powers, and was a judge rather than a mere![]() The reasons for putting the change in or about 462/1 are given by Wade-Gery, , op. cit., pp. 171Google Scholar ff., esp. 174–9; cf. 184–5, 195 The most important piece of evidence is Aesch, . Eumen. 408–89, 566–753.Google Scholar

The reasons for putting the change in or about 462/1 are given by Wade-Gery, , op. cit., pp. 171Google Scholar ff., esp. 174–9; cf. 184–5, 195 The most important piece of evidence is Aesch, . Eumen. 408–89, 566–753.Google Scholar

page 100 note 4 See Gernet, , op. cit. (in p. 96, n. 1 above), pp. 173–200.Google Scholar

page 100 note 5 Arist., Ath. Pol. 58Google Scholar. 2–3. Lipsius, J. H., Das attische Recht und Rechtsverfahren, p. 65Google Scholar and n. 49, and Swoboda, G. Busolt-H., Griechische Staatskunde, iiGoogle Scholar. 1095 and n. 4, limit die jurisdiction of the Polemarch to cases in which metics, etc., were defendants. This is evidently not true of at any rate the fifth century. The Phaselis decree itself must have been intended mainly for the benefit of Phaselite plaintiffs, for reasons which will shortly become apparent; and in the second half of the century five inscriptions (forming a group to be discussed in Part III) show certain favoured foreigners (who either were proxenoi or were given a similar status) receiving the right to sue in the Polemarch's court. Although these inscriptions are fragmentary and need much restoration, their purport, when they are taken together, can hardly be doubted. The clearest of them, for present purposes, are I.G. i2. 153 and 55; the others are I.G. i2. 152 and S.E.G. x. 23 and 108.Google Scholar

page 101 note 1 Op. cit. (in p. 100, n. i above), p. 188 n. 2.

page 101 note 2 Arist, . Ath. Pol. 56Google Scholar. 6–7 557. 2–4; 58. 2–3 59. 1–6. (This of course describes the situation in the 320's, but is likely to apply fo the most part to the fifth century as well. See also, for the duties of the Polemarch Lipsius, J. H., op. cit. (in p. 100, n. 5 above) pp. 63–66Google Scholar, 369–73, 620–6; Swoboda, G. Busolt-H, op. cit. (in the same note), pp 1093–6Google Scholar. For the congestion of the Atheniai courts in the late fifth century, causing Ion; delays, see Ps.-Xen. Ath. Pol. 3. 15Google Scholar. I do not see that we can draw any safe conclusions about the activities in the mid-5tl century of the![]() who are occasionally mentioned in 5th- and early 4th-centur sources (Cratin. fr. 233 [Kock, , C.A.F. i. 83]Google Scholar Ar. fr. 225 [Kock, i. 450]; I.G. i2.41. 4–5, bu see the Meiggs–Andrewes edition of Hill'; Sources, B 54, at p. 303; Lys. 17. 5). See Lipsius, , op. cit., pp. 86–88Google Scholar; Busolt-Swoboda, , op. cit., pp. 1114–15; Hopper, as cited in n. 5 below, at p. 39 and n. 45.Google Scholar

who are occasionally mentioned in 5th- and early 4th-centur sources (Cratin. fr. 233 [Kock, , C.A.F. i. 83]Google Scholar Ar. fr. 225 [Kock, i. 450]; I.G. i2.41. 4–5, bu see the Meiggs–Andrewes edition of Hill'; Sources, B 54, at p. 303; Lys. 17. 5). See Lipsius, , op. cit., pp. 86–88Google Scholar; Busolt-Swoboda, , op. cit., pp. 1114–15; Hopper, as cited in n. 5 below, at p. 39 and n. 45.Google Scholar

page 101 note 3 As Wade-Gery, points out (op. cit., p. 188, n. 3), ‘Clause IV gives its protection only to the Phaselite defendant …: the Phaselite plaintiff could look after himself’ —i.e. he would be able to bring the case in the Polemarch's court from the first. (And see p. 100, n. 5 above.)Google Scholar

page 101 note 4 Here, as sometimes elsewhere, I have for convenience kept in square brackets only those letters which someone might conceivably wish to restore differently.

page 101 note 5 As far as I know, the only scholar who has pointed this out is Hopper, R. J., ‘Interstate Juridical Agreements in the Athenian Empire’, in J.H.S. lxiii (1943), 35–51.Google Scholar

page 101 note 6 This has been fully understood by several scholars. See, for example, Gernet, , op. cit. (in p. 96, n. 1 above), p. 79Google Scholar, n. 4: ‘Le mot![]() s'éetend … à tous les rapports de droit privé; mais il s'applique par préFérence aux rapports contractuels.’ Lipsius, who misinterpreted Clause I of the Phaselis decree (op. cit., p. 966, n. 4), never theless saw that the expression

s'éetend … à tous les rapports de droit privé; mais il s'applique par préFérence aux rapports contractuels.’ Lipsius, who misinterpreted Clause I of the Phaselis decree (op. cit., p. 966, n. 4), never theless saw that the expression![]() . can be applied not only in the narrower sense of ‘Verträge’ but also to ‘Rechtsgeschäfte’ in general (op. cit., pp. 568 and n. 77, 683). See also Wyse, W., The Speeches of Isaeus, pp. 384–5 (note on Isae. 4. 12).Google Scholar

. can be applied not only in the narrower sense of ‘Verträge’ but also to ‘Rechtsgeschäfte’ in general (op. cit., pp. 568 and n. 77, 683). See also Wyse, W., The Speeches of Isaeus, pp. 384–5 (note on Isae. 4. 12).Google Scholar

page 102 note 1 Op. cit., pp. 38–40.

page 102 note 2 In Ps.-Dem. 32. 8–9, where the luthorities in Cephallenia very sensibly order the ship to return to Athens,![]()

![]() might certainly be said to have come into existence at Cephallenia when the dispute arose about where the ship hould go.

might certainly be said to have come into existence at Cephallenia when the dispute arose about where the ship hould go.

page 102 note 3 Another word sometimes used in this sense is![]() see O.G.l.S. 229. 54

see O.G.l.S. 229. 54![]()

![]() and p. 104, n. 2 below.

and p. 104, n. 2 below.

page 103 note 1 Perhaps a![]() as believed by Lipsius, , op. cit. (in p. 100, n. 5 above), p. 775Google Scholar; cf. Arist, . Ath. Pol. 52. 2:

as believed by Lipsius, , op. cit. (in p. 100, n. 5 above), p. 775Google Scholar; cf. Arist, . Ath. Pol. 52. 2:![]() Google Scholar

Google Scholar

page 103 note 2 We are not concerned here with the question how closely Dionysius' Greek reproduces the Latin original, or with the question whether Roman practice in this field was more influenced by the Greeks or by the Etruscans and Carthaginians (cf. Arist, . Pol. 1280a36–40Google Scholar; and see Walbank, F. W., Comm. on Polyb. i. 337 ff., esp. 346). Even if the text bore little relation to the original, it would provide some evidence of Hellenistic legal practice.Google Scholar

page 103 note 3 This misunderstanding dates from at least the time of Hollweg, M. A. von Bethmann, Der römische Civilprozess, i (1864), 67–68.Google Scholar

page 103 note 4 Econ. Survey of Ancient Rome, i. 8.Google Scholar

page 104 note 1 Eth. Nic. 1164b13. Cf. Plato, Rep. 556 a.

page 104 note 2 Eth. Nic. 1131*1–9. See the remarks of Harrison, A. R. W., in J.H.S. Ixxvii (1957), 42 ff., at p. 45.Google Scholar

page 104 note 3 Of course we must not take seriously (as, for example, does Tod, in his notes on the Phaselis decree) these ex parte statements, made purely to create prejudice. The only conclusion we can safely draw is that at die date of the speech, i.e. about the 340's B.C., a large number of Phaselites were trading at Athens, and that they had recently been figuring in a number of lawsuits.

page 104 note 4 Plut, . Cim. 12. 3–4.Google Scholar

page 104 note 5 Bannier's![]() has rightly found no favour.

has rightly found no favour.

page 104 note 6 Op. cit. (in p. 100, n. 1 above), p. 192.

page 104 note 7 The only actual evidence of the exercise of the Athenian![]() in the judicial sphere, before the Chalcis and Miletus decrees (p. 107 below, and D 11 in A.T.L. ii, 57–60Google Scholar) is the Erythrae decree (D 10 in A.T.L. ii, 54–57 = I.G. i2. 10–11 and 12/13a), now dated with considerable probability to 453/2. It is true that the permission given in lines 29–32 to the Erythraean courts, of exiling a homicide from the whole area of the Athenian alliance, would have to be enforced by Athens, if the citizens of a state in which such an exile took refuge snapped their fingers at the Ery thraeans. But claiming to expel an occasional homicide, in accordance with the decision of an allied court, is a very different matter from insisting on the transfer to Athens of a whole class of lawsuits.Google Scholar

in the judicial sphere, before the Chalcis and Miletus decrees (p. 107 below, and D 11 in A.T.L. ii, 57–60Google Scholar) is the Erythrae decree (D 10 in A.T.L. ii, 54–57 = I.G. i2. 10–11 and 12/13a), now dated with considerable probability to 453/2. It is true that the permission given in lines 29–32 to the Erythraean courts, of exiling a homicide from the whole area of the Athenian alliance, would have to be enforced by Athens, if the citizens of a state in which such an exile took refuge snapped their fingers at the Ery thraeans. But claiming to expel an occasional homicide, in accordance with the decision of an allied court, is a very different matter from insisting on the transfer to Athens of a whole class of lawsuits.Google Scholar

page 105 note 1 Thuc. 2. 69. 1 provides evidence that c. 430 Phaselis was at least an important port of call for merchants trading with the Aegean, if not the actual home of such merchants.

page 105 note 2 Xen. de Vect. 3. 3–5Google Scholar; Hipparch. 4. 7Google Scholar; Isocr. 8. 21; cf. Plut, . Lysand. 3.Google Scholar

page 106 note 1 Lipsius, , op. cit. (in p. 100, n. 5 above), p. 966Google Scholar; Busolt-Swoboda, , op. cit. (in the same note), p. 1244, n. 3 (on p. 1245).Google Scholar

page 106 note 2 O.G.I.S. ii. 437, III C, lines 57–59: Google Scholar

Google Scholar

page 106 note 3 There remains that notoriously difficult passage, Ps.-Dem. 7. 13, on which see Appendix C.

page 106 note 4 Cod. Just. 3. 19Google Scholar. 3; cf. 3. 13. 2; 3. 22. 3; Fr. Vat. 325, 326, etc. For criminal cases, see Cod. Just. 3. 13. 5. pr.; 3. 15. 1.Google Scholar

page 106 note 5 Dig. 42. 5. 1–3.

page 106 note 6 Id. 3: ‘contractus autem non utique eo loco intelligitur, quo negotium gestum sit, sed quo solvenda est pecunia.’ Cf. id. 5. 1. 19. 4.

page 106 note 7 Only if it does entertain the action is the English court then confronted with the often difficult question: what is the lex causae— i.e. in a case founded on contract, what is the ‘proper law’ of the contract? See Cheshire, G. C., Private International Law5, chap, iv, esp. pp. 104 ff., and chap, viii, pp. 205 ff. But this problem does not arise in relation to the Phaselis decree. And cf. Appendix C.Google Scholar

page 106 note 8 It is not certain that bottomry (or respondentia) bonds existed in the Greek world as early as the second quarter of the fifth century, although my guess is that they did. The earliest evidence known to me is Lys. 32. 6–7, 14, referring to the year 409. The language used by the speaker seems to me to show that by the time the speech was delivered (i.e. about the turn of the century) bottomry was a familiar institution at Athens. If it was being widely employed as early as the 460's, then many of the contractual ![]() between Athenians and Phaselites at that time may well have arisen out of such loans made by Athenians to Phaselite merchants.

between Athenians and Phaselites at that time may well have arisen out of such loans made by Athenians to Phaselite merchants.

page 107 note 1 To the best of my belief, we do not know whether a plaintiff belonging to a city X could proceed against a defendant of city Y in the courts of a third city, Z. It may well have been possible, if![]() existed between X and Z, though perhaps not otherwise, as a rule.

existed between X and Z, though perhaps not otherwise, as a rule.

page 107 note 2 I would take the appearance of some form of the expression![]()

![]() not later than the early 440's (see, for example, S.E.G. x. 19. 14–15; 23. 8–9), as evidence of the completion of the

not later than the early 440's (see, for example, S.E.G. x. 19. 14–15; 23. 8–9), as evidence of the completion of the![]() Google Scholar

Google Scholar

page 107 note 3 The reason for this should be quite clear from para. 4 above, pp. 105–6.

page 108 note 1 Luria, S., in Vestnik Drevnei Istorii, xx (1947, no. 2), at p. 21 and n. 3. (I have relied mainly upon a translation.)Google Scholar

page 108 note 2 Op. cit. (in p. 101, n. 5 above), p. 42.

page 108 note 3 Op. cit. (in p. 100, n. 1 above), pp. 189–92.