Article contents

The Musical Papyrus: Euripides, Orestes 332–401

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

The version given above is from Murray's Oxford text: the recent Budé text of Chapouthier concurs in accepting Kirchhoff's transposition. Other editors, such as Paley and Weil, have also given their approval to this proposed alteration, though Biehl regards it as superfluous. Most commentators are agreed, however, in considering that the choice must lie between the traditional line-order and Kirchhoff's transposition: few regard the papyrus line-order as either probable or even possible.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1962

References

page 61 note 2 Textprobleme in Euripides Orestes, pp. 24–25.Google Scholar

page 61 note 3 No editors of the play have adopted the papyrus line-order in their text: suggestions that it should be adopted are confined to writers who discuss the papyrus separately—see n. 4.

page 61 note 4 Professor E. G. Turner, to whom we owe the invaluable re-dating of this fragment (J.H.S. lxxvi [1956], 95–96Google Scholar), puts forward some arguments in favour of the papyrus line-order, and quotes Crusius (Philologus lii [1893], 179Google Scholar) in his support. Cf. also Feaver, D. D., A.J.P. lxxxi (1960), 1–15.Google Scholar

page 61 note 5 See Turner, E. G., op. cit., and, in particular, his footnote 8.Google Scholar

page 61 note 6 Cf. Biehl, , loc. cit.Google Scholar

page 62 note 1 Pace Weil, who construes ![]() with

with ![]() understood (see below).

understood (see below).

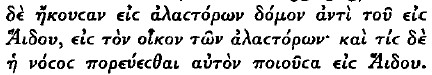

page 62 note 2 Cf. σ ad loc. (Schwartz, 133, 3–5Google Scholar): ![]()

(The reference to

(The reference to ![]() in place of

in place of ![]() or

or ![]() would seem to derive from a confused recollection of the similar phraseology used at vv. 831–3.) Cf. also Schwarz's first footnote on p. 133.

would seem to derive from a confused recollection of the similar phraseology used at vv. 831–3.) Cf. also Schwarz's first footnote on p. 133.

page 62 note 3 Cf. Aesch. Cho. 461: ![]()

![]() For examples of polyptoton with

For examples of polyptoton with ![]()

![]() and Orest. 1308:

and Orest. 1308: ![]()

![]()

page 62 note 4 See Thesaurus Linguae Graecae, s.v., and cf. L.S.J., s.v. In all its other occurrences, including Eur. I. T. 644, the verb governs an accusative. This would seem to illustrate well the usage whereby intransitive verbs are compounded with ![]() to make them transitive : cf. L.S.J., s.v.

to make them transitive : cf. L.S.J., s.v. ![]() E. VI.

E. VI.

page 62 note 5 Cf., for instance, ![]()

![]() (192).

(192).

page 63 note 1 See, for example, Fraenkel on Aesch. Ag. 154 f. (the note on ![]() Sidgwick on Cho. 67; Soph. O.T. 97–98, 101; Eur. Orest. 512–17 (note the phrases

Sidgwick on Cho. 67; Soph. O.T. 97–98, 101; Eur. Orest. 512–17 (note the phrases ![]() and

and ![]()

![]()

page 63 note 2 Cf. Aesch. Ag. 1188–90, Cho. 400–4, 577–8, 649–51, Eum. 230–1, 244–7, 253, 264–6; Soph. frag. 743.

page 63 note 3 Cf. Aesch. Cho. 283–4, Sidgwick on Eum. 358–9; Eur. Orest. 36–37, 411, 423, etc.

page 63 note 4 Schwartz, 134, 12–14.Google Scholar

page 63 note 5 Id. 132, 21–22 (cf. 133, 2–3).

page 63 note 6 See p. 61, nn. 3 and 4.

page 64 note 1 See Turner, E. G., op. cit., p. 95. He adds (p. 96): ‘Now the revised dating of die fragment … means that its aberrant text cannot be dismissed as due to careless copying of the order of lines in the Alexandrian edition. The papyrus must in fact be independent of, perhaps prior to, the Alexandrian tradition.’Google Scholar

page 64 note 2 Turner, E. G. (op. cit., p. 96Google Scholar) points out that ‘it is surely difficult to attribute the text of the papyrus to a mere scribal error. Divergencies from the accepted text that are found in early Ptolemaic “wild” papyri are in general intelligible Greek, that is, they are at least possible variants. Under what conditions, however, is it possible to conceive the displacement of phrases in a lyric text that is “protected” by musical notation (both of nitrh and rhvthm)?’

page 64 note 3 I have not seen this principle expressed as a maxim, though it seems as useful a canon as Difficilior lectio potior. Perhaps Impossibilis lectio verae propior: I owe this formulation to a discussion with Mr. S. A. Handford.

page 64 note 4 Cf, for instance, the variant readings at Juvenal 8. 148: sufflamine multo consul and multo sufflamine consul, where the former reading, though metrically impossible, is, in comparison with its more plausible alternative, far nearer to the true reading, sufflamine mulio consul. Similarly, at Virgil, , Georgics 4. 412, the reading tantu, as opposed to tantum and the highly plausible tanto, enabled Ribbeck to restore the true reading, tarn tu.Google Scholar

page 64 note 5 Or, with equal probability, ![]()

![]() for

for ![]() if the corruption occurred in a text which had

if the corruption occurred in a text which had ![]() for

for ![]()

page 66 note 1 Another, and incidental, advantage derives from, the adoption of this reading. With the change from ![]() the papyrus lineorder yields an acceptable sense, and this vindication of the papyrus text should enable students of Greek music to Ceel greater confidence in the authenticity and integrity of the accompanying musical score—virtually the oldest piece of written evidence in the study of ancient Greek music. The supposed dislocation of the text has naturally lent countenance to grave doubts concerning the music's Euripidean authorship [cf. Mrs. Henderson, , New Oxford History of Music, i. 337Google Scholar], concerning its accurate transmission [cf. Turner, E. G., who states the problem well (op. cit., p. 96, n. 10)Google Scholar: ‘In that case, has the scribe got both words and musical notation in the wrong order, or have the words and music got out of phase?’], and concerning its general interpretation [cf. Mountford, J. F., Greek Music in the Papyri and Inscriptions {New Chapters in Greek Literature, edited by Powell, and Barber, — Second Series), p. 149, who writes: ‘Yet any conclusions which we are inclined to draw from this fragment will always be open to some doubt, since the order of the lines in the papyrus is different from that upon which modern scholars are agreed.’ Cf., also, his n. 1 on that page]. These doubts are dispelled if, by the adoption of the suggested reading, we no longer need to assume any dislocation, or, indeed, any corruption whatsoever, in the papyrus text.Google Scholar

the papyrus lineorder yields an acceptable sense, and this vindication of the papyrus text should enable students of Greek music to Ceel greater confidence in the authenticity and integrity of the accompanying musical score—virtually the oldest piece of written evidence in the study of ancient Greek music. The supposed dislocation of the text has naturally lent countenance to grave doubts concerning the music's Euripidean authorship [cf. Mrs. Henderson, , New Oxford History of Music, i. 337Google Scholar], concerning its accurate transmission [cf. Turner, E. G., who states the problem well (op. cit., p. 96, n. 10)Google Scholar: ‘In that case, has the scribe got both words and musical notation in the wrong order, or have the words and music got out of phase?’], and concerning its general interpretation [cf. Mountford, J. F., Greek Music in the Papyri and Inscriptions {New Chapters in Greek Literature, edited by Powell, and Barber, — Second Series), p. 149, who writes: ‘Yet any conclusions which we are inclined to draw from this fragment will always be open to some doubt, since the order of the lines in the papyrus is different from that upon which modern scholars are agreed.’ Cf., also, his n. 1 on that page]. These doubts are dispelled if, by the adoption of the suggested reading, we no longer need to assume any dislocation, or, indeed, any corruption whatsoever, in the papyrus text.Google Scholar

page 66 note 2 Cf., for example, Pindar, , Pyth. 11. 21Google Scholar; Aristophanes, , Pax 126 (the only occurrence, in this author, of the word in its active form); Eur. H.F. 838, 1278, Rhes. 832, Ale. 443, 1073.Google Scholar

page 66 note 3 For this identification, cf. Roscher, , Lexicon der Mythologie, s.v. Alastor (d), Page on Medea 1259–60 (p. 169 in his edition)Google Scholar, Pearson on Phoen. 1556. Note also the verb ![]() used of the

used of the ![]() at I. T. 970–1:

at I. T. 970–1: ![]()

![]() (cf. ibid. 934).

(cf. ibid. 934).

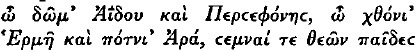

page 67 note 1 For their home in Hades (Hades and Persephone are, according to the more ancient tradition, their parents), cf. Roscher, , op. cit., s.v. Erinys (1318–20)Google Scholar; Aesch, . Eum. 72, 115, 395–6Google Scholar; Soph, . O.C. 40, 1568, El. 489–91Google Scholar; Eur, . I.T. 286Google Scholar. For the Erinyes as avengers who set out from the lower world, drive their victim to death, and then punish him in Hades, cf. Roscher, , op. cit., s.v. Erinys (1324–5)Google Scholar; Homer, , r 278–9, I 569–72, T 258–60Google Scholar; Pindar, , Ol. 2. 41–42Google Scholar; Aesch, . Eum. 267–75, 338–40, 368Google Scholar; Soph, . O.C. 1432–4. Euripides, in our play, represents Orestes as fearing the Erinyes not only as tormentors of the living but also as bringers of death (and punishment thereafter): ![]()

![]()

![]() (264–5).Google Scholar

(264–5).Google Scholar

page 67 note 2 Thus in Homer we find not only ![]()

![]() but also the more enterprising

but also the more enterprising ![]()

![]() (K 491). In close company with Hades and Persephone, in references to the lower world, are found their offspring (see n. 1, above), the Erinyes. Prayers to the parents are answered by die children, and conversely: cf.

(K 491). In close company with Hades and Persephone, in references to the lower world, are found their offspring (see n. 1, above), the Erinyes. Prayers to the parents are answered by die children, and conversely: cf. ![]()

![]()

![]() (I 569, 571–2), and

(I 569, 571–2), and ![]()

![]()

![]() (1454, 456–7). In Pindar, besides the conventional

(1454, 456–7). In Pindar, besides the conventional ![]()

![]() (Pyth. 3. 11Google Scholar), we find die designation by Persephone alone:

(Pyth. 3. 11Google Scholar), we find die designation by Persephone alone: ![]()

![]() (Ol. 14. 20–21Google Scholar), and

(Ol. 14. 20–21Google Scholar), and ![]()

![]() (Isthm. 8. 60Google Scholar). In Sophocles the offspring again figure with dieir parents in a comprehensive invocation of the lower world:

(Isthm. 8. 60Google Scholar). In Sophocles the offspring again figure with dieir parents in a comprehensive invocation of the lower world:

![]() (El. 110–12: cf. O.C. 40, Ant. 1075); a more recondite reference to the lower world is

(El. 110–12: cf. O.C. 40, Ant. 1075); a more recondite reference to the lower world is ![]() (O.C. 1564). Euripides uses a variety of periphrases: besides

(O.C. 1564). Euripides uses a variety of periphrases: besides ![]()

![]() (Heracl. 913), we find

(Heracl. 913), we find ![]()

![]() (H.F. 808),

(H.F. 808), ![]()

![]() (Ale. 851–2), and

(Ale. 851–2), and ![]() (Ale. 1073): Cf.

(Ale. 1073): Cf. ![]()

![]() (Hec. 1–2). In a context, dierefore, where it is plain that

(Hec. 1–2). In a context, dierefore, where it is plain that ![]() (see p. 65, n. 3), there is no reason why Euripides should not designate the lower world by mention of these other inhabitants. For

(see p. 65, n. 3), there is no reason why Euripides should not designate the lower world by mention of these other inhabitants. For ![]() dwelling in Hades, cf. Medea 1059:

dwelling in Hades, cf. Medea 1059: ![]()

- 1

- Cited by