Article contents

The Language of Odyssey 5.7–20

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

The old Analytical view that the union between the Journey of Telemachus and the rest of the Odyssey is post-Homeric, superficial, and incompetently effected is nowadays widely rejected, and rightly so. However, although many defences cumulatively, I believe, successful–of the content of the second divine assembly have been put forward in recent years, no adequate answer has yet been given to the objections raised against the allegedly anomalous language of Athene's speech of 5.7–20:

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1977

References

1 e.g. Bérard, V., Introduction à l'Odyssée (Paris, 1924–1925), iii. 226–37Google Scholar; Von der Mühll, P., R.E. Suppl. vii (1940), 711Google Scholar; Merkelbach, R., Untersuchungen zur Odysse Zetemata ii (Munich, 1951, 2nd edn. 1969) p. 156. Od. 5.8–12 = 2.230–4; 5.14–17 = 4.557–60; 5.19–20 = 4.701–2.Google Scholar

2 The Homeric Odyssey (Oxford, 1955), p. 72Google Scholar, cf. p. 68. It is worth stressing that this is Page's view: F.M. Combellack refers erroneously to Page's ‘conviction that the story of Telemachus is a later addition to the Odyssey’ (Gnomon, 28 (1956)Google Scholar, 412), and similarly G.P. Rose wrongly asserts that ‘Denys Page … (has) argued that the “Telemachy” does not belong integrally to the Odyssey’ (TAPA 98 (1967), 392): they have presumably been misled by the general tone of the introduction to Page's Chapter III and by the stress which he lays on certain alleged incongruities, but his eventual conclusion is actually the very opposite of what they claim.Google Scholar

3 Op. cit., p. 71; similarly Kirk, G.S., The Songs of Homer (Cambridge, 1962), pp. 233–4.Google Scholar

4 Op. cit., pp. 70–1; echoed by Kirk, , op. cit., p. 233.Google Scholar

5 Ant. Class. 35 (1966), 28.Google Scholar

6 The Art of the Odyssey. (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1967), pp. 49–50.Google Scholar

7 Beiträge zum Verständnis der Odyssee (Berlin, 1972), p. 128.Google Scholar

8 ‘The Second Assembly of the Gods in the Odyssey’, Antichtbon 4 (1970), 1–12, esp. 1, 11.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

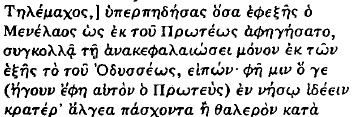

9 To simplify matters Page ignored this completely in his text (‘her second sentence, in four lines’ excludes line 13) but discussed it briefly in his notes (p. 81 n.17): ‘Od. 5. 13 = II. 2.721: as the Scholia say, ![]()

![]() is suitable there, but not here…’

is suitable there, but not here…’

10 For this term see Nagler, M.N., TAPA 98 (1967), 281.Google Scholar

11 L'Epithéte traditionelle dans Homère (Paris, 1928), pp. 89–93Google Scholar; HSCP 41 (1930), 140–3Google Scholar. See also Nagler, , loc. cit. 274–310.Google Scholar

12 pp. vii–ix of the Preface to Vol. I of his edition of the Odyssey (London, 1866). His remarkable anticipation of Parryism is well worth quoting: ‘The manner of the poet's handling his machine of language seems to me to confirm its purely unwritten character. The love of iterative phrase, and the perpetual grafting of one set of words on another, the great tenacity for a formulaic cast of diction and of thought, and the apparent determination to dwell in familiar cadences, and to run new matter in the same moulds, all seem to me to mark the purely recitative poet ever trading on his fund of memory.’Google Scholar

13 The meaning of the first half of the scholium is; ‘This line occurs more appropriately in the Iliad apropos of Philoctetes.’ Bérard, (op. cit. iii. 227) strangely misinterprets it as ‘The word ![]() is more appropriate in the Iliad'–but that would require

is more appropriate in the Iliad'–but that would require ![]() and is hardly compatible with the second half of the scholium. In any case, Berard's own objection to the use of

and is hardly compatible with the second half of the scholium. In any case, Berard's own objection to the use of ![]() in Od. 5.13, ‘Ulysse chez Calypso n'est pas “gisant”’, cannot be sustained, since the word is used elsewhere in Homer, like

in Od. 5.13, ‘Ulysse chez Calypso n'est pas “gisant”’, cannot be sustained, since the word is used elsewhere in Homer, like ![]() of a general state of inactivity or immobility, e.g. Il. 2.771–2 = 7.229–30 (formulaically related to Od. 5.13, as we have seen) and, I would say, Il. 2.721 itself. Moreover, if we are to insist on being literalists we can point out that Odysseus is literally ‘lying’ while he is actually

of a general state of inactivity or immobility, e.g. Il. 2.771–2 = 7.229–30 (formulaically related to Od. 5.13, as we have seen) and, I would say, Il. 2.721 itself. Moreover, if we are to insist on being literalists we can point out that Odysseus is literally ‘lying’ while he is actually ![]()

![]() (5.14): see 5.151–8.Google Scholar

(5.14): see 5.151–8.Google Scholar

14 Above, n.9.

15 Cf. p. 139 of Rothe, C., ‘Die Bedeutung der Wiederholungen für die homerische Frage’, Festschrift zur Feier des 200 jäbrigen Bestehens des französischen Gymnasiums (Berlin, 1890), pp. 123–68Google Scholar. This point has been missed by Bérard, who assumes that 4.559–60, 5.16–17, and 17.145–6 have all been copied from 5.141–2, where he claims ‘tout … est logique et nécessaire’ (op. cit. iii. 229–30).Google Scholar

16 It may be objected that the meaning is actually ‘I do not have any ships with me or any companions of [or: for] Odysseus’, but this exegesis, though possible, rather strains the syntax, a fact which would again strongly suggest that the lines were not specially composed for this place.

17 Depending on the exigencies of the metre the Homeric poet can and does use a long line-ending ![]()

![]() etc., an intermediate one

etc., an intermediate one ![]()

![]() etc., or a short one

etc., or a short one ![]()

![]() etc. The intermediate form occurs at Il. 1.413, 6.459 (after

etc. The intermediate form occurs at Il. 1.413, 6.459 (after ![]() ), 18.94,428.

), 18.94,428.

18 Is there any external evidence for a varia lectio ![]() in Od. 17.142? Bérard, (op. cit. iii. 229) tells us with supreme confidence that ‘Eustathe nous donne le texte vrai … ’ However, whether or not this is the ‘texte vrai’, it is not exactly what Eustathius ‘nous donne’. The extraordinary note in Eustathius (1813. 16–20) on Od. 17.142 must be quoted in full:

in Od. 17.142? Bérard, (op. cit. iii. 229) tells us with supreme confidence that ‘Eustathe nous donne le texte vrai … ’ However, whether or not this is the ‘texte vrai’, it is not exactly what Eustathius ‘nous donne’. The extraordinary note in Eustathius (1813. 16–20) on Od. 17.142 must be quoted in full: ![]()

![]() … Eustathius unmetrical

… Eustathius unmetrical ![]() is of course a conflation of od. 5.13

is of course a conflation of od. 5.13 ![]() and 17.142

and 17.142 ![]()

![]() and his

and his ![]() unmetrical in 17.142, is what Proteus actually said in Od. 4.556. Does Eustathius really mean to give us an alternative text here? Probably; the simpl

unmetrical in 17.142, is what Proteus actually said in Od. 4.556. Does Eustathius really mean to give us an alternative text here? Probably; the simpl![]() is his usual way of introducing a variant, he professes to be quoting Telemachus

is his usual way of introducing a variant, he professes to be quoting Telemachus ![]() and the Greek could not logically mean ‘but the actual words of Proteus were

and the Greek could not logically mean ‘but the actual words of Proteus were ![]() But why has he got into such a terrible muddle? 1 suspect that in one of his sources he had hastily read a scholium pointing out that Telemachus' version of what Proteus said was different from Menelaus’ (and perhaps also quoting the ending of 5.13), and that he misunderstood the scholium's citation of the latter half of 4.556 as a variant or emendation in 17.142. However, it is admittedly possible that there really was a variant

But why has he got into such a terrible muddle? 1 suspect that in one of his sources he had hastily read a scholium pointing out that Telemachus' version of what Proteus said was different from Menelaus’ (and perhaps also quoting the ending of 5.13), and that he misunderstood the scholium's citation of the latter half of 4.556 as a variant or emendation in 17.142. However, it is admittedly possible that there really was a variant ![]() (without

(without ![]() ), and that Eustathius' confusion is due to his having studied all three passages (5.13 ff., 4.556 ff., 17.142 ff.) before writing his note and remembered them badly. In that case I would argue that the unanimity of the extant MSS. in reading

), and that Eustathius' confusion is due to his having studied all three passages (5.13 ff., 4.556 ff., 17.142 ff.) before writing his note and remembered them badly. In that case I would argue that the unanimity of the extant MSS. in reading ![]() favours the hypothesis that the variant is an isolated scholarly correction to align Telemachus' report with what Proteus ‘actually’ said.Google Scholar

favours the hypothesis that the variant is an isolated scholarly correction to align Telemachus' report with what Proteus ‘actually’ said.Google Scholar

19 Dimock, G.E., Jr., Arion 2.4 (Winter 1963), 41, 44.Google Scholar

20 If the Journey of Telemachus could hardly have been viable as an independent poem, yet forms an excellent introduction to our Odyssey, the natural conclusion is that it was composed specially for that purpose. See e.g. the Appendix to Monro's, D.B. edition of Od. 13–24 (Oxford, 1901), pp. 309–10Google Scholar; Woodhouse, W.J., The Composition of Homer's Odyssey (Oxford, 1930), pp. 210–11.Google Scholar

21 An exception is Od. 5.13 in so far as it almost = Il. 2.721, but 1 have already given a special explanation of this line.

22 ‘Continuity and Interconnexion in Homeric Oral Composition’, TAPA 82 (1951), 81–101, esp. 91–5.Google Scholar

23 Op. cit. 94.

24 e.g. it has often been pointed out that 5.18–20 refer to events which have occurred after the first assembly.

25 Aristarchus athetized 7.251–8, but we do not need to suppose that he had any external evidence against the passage, and even if it is an interpolation the central point of my argument remains unaffected, since the athetesis does not touch 249–50.

26 Other examples of this kind of repetition include Od. 10.252–8 based on parts of 10.210–32 and Il. 1.372–9 = 1.13–16, 22–5; Il. 1.372–9 fall within a mammoth Aristarchean athetesis (of 366–92), but, again, we are not obliged to take this seriously, since the scholia rrtake no mention of manuscript omissions.

27 I here append some other verbally repetitive passages within summaries, even though their value as parallels to Od. 5.8–20 may in each case be queried for one reason or another: (1) Il. 18.437–43 = 56–62; 18.444–5 (Thetis to Hephaestus) almost = 16.56, 58 (AchIlles to Patroclus); (2) Od. 13.380–1 (Athene to Odysseus) = 2.91–2 (Antinous to Telemachus); (3) Od. 23.335–7 almost = 5.135–6, 7.256–8; 23.339–41 almost = 5.36–8.

28 The general point that Homer's recapitulations tend to be verbally repetitive was made in passing by Pfudel, E. (Die Wiederbolungen bei Homer: I. Beabsichtigte Wiederholungen (Liegnitz, 1891), p. 8Google Scholar), who did not mention Od. 5.8–20, and at greater length in an unpublished dissertation by Seitz, E.‘Die Stellung der “Telemachie” im Aufbau der Odyssee’, (Marburg, 1950), pp. 36–45), whose object was to defend the authenticity of the passage Od. 13.375–81 against the Analysts' charges that it is a cento. However, Seitz did not discriminate adequately between the various kinds of repetition which Homer's summaries contain, he lumped together instances of true repetition with cases where there is no real verbal repetition at all (p. 40 n.l), and he gave the Odyssey's second divine assembly only a fleeting mention (as 5.1–28: p. 41 n.l).Google Scholar

- 2

- Cited by