Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Spranger's Preliminary Skeleton List of the Manuscripts of Euripides (C.Q. xxxiii [1939], 98–107) mentions four gnomological manuscripts:

The first and the third of these manuscripts contain miscellaneous excerpts of many classical and scriptural authors, arranged under various subject headings; though some of the excerpts are Euripidean, these manuscripts have no more right to be classified as Euripidean than have the manuscripts of Orion or Stobaeus. They are, therefore, wrongly included in Spranger's list.

page 129 note 2 See Bandini, , Catalogus codicum manuscriptorum bibliothecae Mediceae Laurentianae, pp. 252–5.Google ScholarCf. Turyn, , op. cit., p. 93 n. 151.Google Scholar

page 129 note 3 See Voltz, L. and Crönert, W., Centralblatt für Bibliothekswesen, xiv. 537–71.Google Scholar

page 129 note 4 Mr. Spranger's list was, as he himself has made clear, only intended to be provisional. Incidentally, manuscript no. 237 on that list (Vatopedi 738/25) is not a text of Medea, but a paraphrasis of that play written in ‘modern’ Greek. For some omis sions in the list, see n. 9 (on this page). [The list is now superseded, except for manuscriptirecentissimi, by Turyn, , op. cit., pp. 3–9.]Google Scholar

page 129 note 5 See Zanetti, Graeca D. Marci Bibliotheca codicum manu scriptorum per titulos digesta, p. 272Google Scholar See also Turyn, , op. cit., p. 93.Google Scholar

page 129 note 6 See Sophronios Eustratiades and Arcadios, ‘Catalogue of the Greek Manuscripts in the Library of the Monastery of Vatopedi on Mt. Athos, ’ (Harvard Theological Studies, xi, 1924), p. 13Google Scholar. See also Turyn, , op. cit., pp. 92–93.Google Scholar

page 129 note 7 I am deeply indebted to the Oxford Craven Committee for financial support in this investigation, to Mr. W. S. Barrett of Keble College for much assistance and advice, to Mr. T. C. Skeat of the British Museum, to Dr. Paul Maas, and to Mr. J. A. Spranger, for giving expert opinions on a number of points. My thanks are also due to the Institut de Recherche et d'Histoire des Textes, Paris, and to the librarians of all the libraries mentioned above.

page 129 note 8 i.e. each codex-Marcianus 507 and Vatopedianus 36. The Vatopedi reference ‘36/7’ refers to the specifically Euripidean section of that manuscript.

page 129 note 9 Others, doubtless, exist. Turyn, , op. cit., PP. 93–94 n, 151Google Scholar, describes two such manuscripts: Vatic. Barberini gr. 4 and Escorial X.I. 13. One may add that Devreesse, R., Codices Vaticani Graeci, iii. 196 ff.Google Scholar, lists, under the number 711, a manuscript ‘saec. xrv ex.’ containing ‘tragicorum sententiae selec–tae, nempe (ff. 121–123) Euripidis, (ff. I23v–I25) Sophoclis, (ff. 125–126) Aeschyli.‘ Also, Papadoulos-Kerameus, ‘![]()

![]() ii. 572, lists, under the number 507, a manuscript

ii. 572, lists, under the number 507, a manuscript ![]()

![]() containing

containing ![]()

![]() .

.

page 130 note 1 Cf. Horna, K., Gnome, Gnomendichtun Gnomologien (P.–W. Suppl. vi), p. 84Google Scholar, and Wilamowitz, , Einleitung, p. 171 n. 101.Google Scholar

page 130 note 2 Murray, O.C.T. Eur. I, praef. vii–viii, terms it ‘Gnomologia Veneta’ (feminine), but elsewhere, in his apparatus criticus, he uses the more normal neuter form of the word.

page 130 note 3 Loc. cit.

page 130 note 4 Acta Societatis Philologae Lipsiensis, vi. 333–5.Google Scholar

page 130 note 5 Wiener, Studien, xi. 309–14.Google Scholar

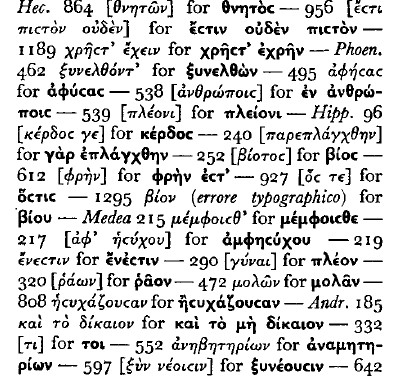

page 130 note 6 Schenkl's collation is by Kirchhoff's text (though he uses Prinz';s sigla in references to other manuscripts). The following inaccuracies are noteworthy (Murray's numeration: readings inferred ex silentio are in square brackets: readings derived from my own collation are in heavy type):

![]() Schenkl omits to mention that the gnomology contains Hipp. 1441 (wim a variant) and Andr. 644: he includes, on the other hand, Hipp. 1023, which the gnomology does not contain. In addition, his ascriptions of initial capitals, when he quotes the first word of a passage, are incorrect more often than not (cf. Medea 964, Ale. 195, 548–9, 679, 960, Rhes. 159, 394). ‘The above list contains all but the most minor explicit inaccuracies: of implicit inaccuracies only some of the most important are mentioned, since that collation makes no claim to be exhaustive.] Schenkl's

Schenkl omits to mention that the gnomology contains Hipp. 1441 (wim a variant) and Andr. 644: he includes, on the other hand, Hipp. 1023, which the gnomology does not contain. In addition, his ascriptions of initial capitals, when he quotes the first word of a passage, are incorrect more often than not (cf. Medea 964, Ale. 195, 548–9, 679, 960, Rhes. 159, 394). ‘The above list contains all but the most minor explicit inaccuracies: of implicit inaccuracies only some of the most important are mentioned, since that collation makes no claim to be exhaustive.] Schenkl's ![]() , at Alc. 680, is odd: the p and the rough breathing are clear (for the p cf.

, at Alc. 680, is odd: the p and the rough breathing are clear (for the p cf. ![]() in the line above), and the πr compendium, though somewhat cramped, is quite distinct from π (for a similarly cramped πr compendium, cf.

in the line above), and the πr compendium, though somewhat cramped, is quite distinct from π (for a similarly cramped πr compendium, cf. ![]() at Orest. 603). Odd, too, is his

at Orest. 603). Odd, too, is his ![]() at Alc. 703: the

at Alc. 703: the ![]() and γ are perfectly normal, though the α, which is open at the top and with a long final stroke, might be confused with an open ω.

and γ are perfectly normal, though the α, which is open at the top and with a long final stroke, might be confused with an open ω.

page 130 note 7 Loc. cit.

page 131 note 1 Miller, E., Archives des misions scientifiques et litteraires, IIe série, 2 (1865), p. 506Google Scholar, mentioned seeing, on Athos, a ‘chrestomathie’ containing separate sections of excerpts from Homer, Euripides, and Sophocles, but he gave no further description, nor any precise details as to its location. Krumbacher, , Hist.der Byz. Lit.2, p. 602 n. 5Google Scholar, points to the similarity in contents between the manuscript seen by Miller and the Venice one. Rudberg, S.Y.,Eranos, liv (1956), 177Google Scholar, describes the manuscript as ‘un recueil gnomologique qu'il vaudrait la peine d'étudier de plus près’, but his mention of its contents evidently derives from the Vatopedi catalogue, since it reveals the same serious mistake (see below).

page 131 note 2 Thus, for instance, amongst the rubricated capitals, the capital M is formed in two ways. Sometimes it is written with straight lines, like the modern printed form, and sometimes it is written with curved lines, like a minuscule μ written larger. In the six places where G has the square form (Hipp. 93, 328, 1083, Andr. 229, Rhes. 333, 482), g also has the square form: in three other places where G has the curved form (Orest. 450, Hipp. 1441, Medea 807), g also has the curved form. In two other places (Hipp. 1257, Medea 598), however, die curved form is used in G and the square iorm in g.

page 131 note 3 Compendia are used far less frequently by g than by G; this is because G uses them constantly throughout the manuscript, while g, with a few exceptions (cf. p. 132 § c), uses them only at the end of a line, in order to preserve the right-hand margin. On the other hand, G and g agree in their use of certain of the more common contractions, such as ![]()

![]()

![]() . They also agree in the few cases where such contractions are not used:

. They also agree in the few cases where such contractions are not used: ![]() , written out in full, at Hipp. 425,

, written out in full, at Hipp. 425, ![]() at Phoen. 406,

at Phoen. 406, ![]() at Andr. 230. Similarly, both manuscripts abbreviate

at Andr. 230. Similarly, both manuscripts abbreviate ![]() in the first title–heading (Hecuba) by writing the δ above the preceding

in the first title–heading (Hecuba) by writing the δ above the preceding ![]() and omitting on, but in the other title–headings both manuscripts write out the word in full. At Alc. 722 both manuscripts contract

and omitting on, but in the other title–headings both manuscripts write out the word in full. At Alc. 722 both manuscripts contract ![]() , though

, though ![]() and its derivatives are not elsewhere contracted. At Hipp. 1295, again, both manuscripts agree in an abbreviation of

and its derivatives are not elsewhere contracted. At Hipp. 1295, again, both manuscripts agree in an abbreviation of ![]() with an oblique line, an abbreviation more drastic than any other found in these manuscripts, and in an abbreviation of

with an oblique line, an abbreviation more drastic than any other found in these manuscripts, and in an abbreviation of ![]() , a word which is only abbreviated elsewhere, in bom manuscripts, at Hipp. 694.

, a word which is only abbreviated elsewhere, in bom manuscripts, at Hipp. 694.

page 132 note 1 Cf., for example, the collations at Orest. 543, Phoen. 501, Hipp. 612, 986, Andr. 190, 419, 552, Alc. 179, 351.

page 132 note 2 Cf., for example, the collations at Hec. 816, Orest. 3, Hipp. 472, 643, Medea 543, Alc. 376, 788.

page 132 note 3 See ‘HANDS’, below, and p. 134 n. 1.

page 132 note 4 Written ![]() : see p. 131, n. 3.

: see p. 131, n. 3.

page 132 note 5 A simple error, since the compendium used by G for ![]() is similar in shape to ζ: for the possibility of confusion, cf., from the same manuscript, ζ and

is similar in shape to ζ: for the possibility of confusion, cf., from the same manuscript, ζ and ![]() in

in ![]() at Hipp. 432.

at Hipp. 432.

page 132 note 6 E.g. T with a sign which, from its size and position, might represent either an apostrophe or the compendium for Eσ. In the collations I give what seems the more probable alternative.

page 132 note 7 This hypothesis would depend upon the assumption, necessary to explain the omitted line, that G has preserved, in that place, at any rate, the lineation of his exemplar. Such correspondence of lineation does occur: we find, for example, in g, manuscript lines which correspond exactly witfi those of G, not only in places where both manuscripts have begun an excerpt with a new line (e.g. Orest. ![]() ), but also in places where the manuscript line begins with half a word (e.g. Orest. 450–1:

), but also in places where the manuscript line begins with half a word (e.g. Orest. 450–1: ![]() , and Orest. 1156–7:

, and Orest. 1156–7: ![]() ). But that g should happen to omit a line in just one such place where G and its exemplar correspond would be a remarkable coincidence.

). But that g should happen to omit a line in just one such place where G and its exemplar correspond would be a remarkable coincidence.

page 133 note 1 As Dr. Maas has pointed out to me, should any one wish to assert that g is a witness independent of G, when G is, apparently, the older manuscript, the onus of proof lies with the person who makes that assertion, not widi the person who denies it. [Turyn, , op. cit., p. 92Google Scholar, has not led me to alter my opinion that g is directly descended from G. He gives it as his surmise that the two manuscripts are gemelli, but makes no claim to have examined the matter in detail. He quotes (p. 93 n. 149) the heading of Phoenissae in g as ![]()

![]() , and infers that g's source read

, and infers that g's source read ![]() (the reading found in G). This fits my theory, though it is not inconsistent with his. Turyn suggests that the Venice scribe ‘wrote die title correctly, but then erased

(the reading found in G). This fits my theory, though it is not inconsistent with his. Turyn suggests that the Venice scribe ‘wrote die title correctly, but then erased ![]() to conform with his source’. My own observations do not lead me to believe that

to conform with his source’. My own observations do not lead me to believe that ![]() , or any odier letter, has been erased: perhaps the scribe, seeing that his exemplar was incorrect, simply left a space for subsequent correction— he appears to have done the same thing at Rhesus 759 (see collations).].

, or any odier letter, has been erased: perhaps the scribe, seeing that his exemplar was incorrect, simply left a space for subsequent correction— he appears to have done the same thing at Rhesus 759 (see collations).].

page 133 note 2 The cover of die Venice manuscript is marked ‘Provenienza Bessarione’, and the manuscript was evidently part of Cardinal Bessarion's library, donated to the Biblioteca di San Marco in 1468. For the formation of Bessarion‘s library, see Vast, , Le Cardinal Bessarion, pp. 364–78Google Scholar; for its contents, see Omont, , Revue des Bibliothèques,iv. 129–87Google Scholar, and, for its transference to Venice, see Morelli, , Delia Publico Libreria di San Marco in Venezia Dissertazione StoricaGoogle Scholar, Capo II. Bessarion would have had ample opportunity to acquire manuscripts derived from Mt. Athos [see Rudberg, S.Y., Eranos, liv (1956), 174].Google Scholar

page 133 note 2 A number of collators have, in my opinion, made extravagant claims in their identification of manuscript hands: a noteworth instance from the Euripidean collations is the distinction drawn between L2 and l, where one is often at a loss to discover the collator's criteria. (Mr. Barrett confirms this point from his experience of die Hippolytus collations.) Since a single letter added to a text must, of necessity, be shaped in accordance widi die available space, and may well be adapted to conform widi die writing into which it is interpolated, the colour of die ink must often be the only available palaeographic criterion. Other criteria, of a logical type, are, however, permissible: cf. Spranger, , C.Q. xxxiii. 186.Google Scholar

page 134 note 1 Maas and Skeat confirm these datings. In the case of G, they agree with the catalogue, regarding the hand as ‘typically’ twelfth-century. Skeat points out that the square breathings, used throughout the manuscript, suggest a date early in the twelfth century. In the case of G2, only the supplement which I have mentioned (![]() ) is long enough to be dated. The writing is not dissimilar to that of g. In the case of G3, the writing of the third major interpolation (Hec. 328–31) is clearly fourteenth-century, and the writing of the other two interpola tions (Hec. 291–3; 317–20 and 332), though somewhat cramped through lack of space, is clearly by the same hand. In the case of g, Maas and Skeat agree with Schenkl, who writes (op. cit., p. 309): ‘codex ille scriptus est si quid video aut saeculo XII exeunteaut ineunte XIII.’.Google Scholar

) is long enough to be dated. The writing is not dissimilar to that of g. In the case of G3, the writing of the third major interpolation (Hec. 328–31) is clearly fourteenth-century, and the writing of the other two interpola tions (Hec. 291–3; 317–20 and 332), though somewhat cramped through lack of space, is clearly by the same hand. In the case of g, Maas and Skeat agree with Schenkl, who writes (op. cit., p. 309): ‘codex ille scriptus est si quid video aut saeculo XII exeunteaut ineunte XIII.’.Google Scholar

page 134 note 2 I have included many minor orthographic oddities which, though equally prevalent in the other Euripidean manuscripts, are only sporadically reported from them. Amongst these are:

(i) the marking of erases as if they were elisions – contrast, in Gg, ![]() at Hipp. 1001 with

at Hipp. 1001 with ![]() at Hipp. 987 — cf. Spranger, , C.Q. xxxiii (1939), 185 n. 3;Google Scholar

at Hipp. 987 — cf. Spranger, , C.Q. xxxiii (1939), 185 n. 3;Google Scholar

(ii) vagaries of word–division: ![]()

![]() (cf.Gardthausen, , Gr. Palaeographie2, ii. 399);Google Scholar

(cf.Gardthausen, , Gr. Palaeographie2, ii. 399);Google Scholar

(iii) accentual vagaries:

(a)in adverbs, such as ![]()

![]() ,

,

(b)in nouns, such as ![]()

![]() , and the accusative plurals

, and the accusative plurals ![]()

(c)in verbs, such as ![]() and the participles

and the participles ![]()

![]()

(d)in enclitics: cf. ![]()

![]()

I have also included examples of ‘diacritic’ apostrophe ![]() : cf.Gardthausen, , op. cit., p. 398)Google Scholar, and of ‘inter-aspirates’(

: cf.Gardthausen, , op. cit., p. 398)Google Scholar, and of ‘inter-aspirates’(![]()

![]() cf. ibid., pp. 385–6). These I have not observed in the other Euripidean manuscripts, though they may occur.

cf. ibid., pp. 385–6). These I have not observed in the other Euripidean manuscripts, though they may occur.

page 134 note 3 C.Q. xxxii. 200Google Scholar. Cf. Page, , Medea, p. iii.Google Scholar

page 134 note 4 It is not, of course, suggested that apparatus criticishould contain all such details as are included in the present collation. The full collations should be published separately, editorum in usum. The aim of such full collations is not solely the detection of leitfehler. They also enable us to gain a deeper understanding of the manuscript through acquaintance with its characteristic faults. Thus, for instance, in Gg, ![]() (for

(for ![]() ) at Medea 231, together with many similar examples of wrongly accented enclitics (see n. 2 (iii, d,) on this page) shows that at Medea 408

) at Medea 231, together with many similar examples of wrongly accented enclitics (see n. 2 (iii, d,) on this page) shows that at Medea 408 ![]()

![]() is, on the scribal evidence, no less likely than

is, on the scribal evidence, no less likely than ![]() So, too, a comparison of the readings at Hipp. 614, Medea 195, Andr. 230 and 697 suggests that

So, too, a comparison of the readings at Hipp. 614, Medea 195, Andr. 230 and 697 suggests that ![]()

![]() at Hipp p. 323, though it may be a simple miswriting of

at Hipp p. 323, though it may be a simple miswriting of ![]()

![]() , might well be regarded as virtually equivalent to

, might well be regarded as virtually equivalent to ![]() , and this, perhaps, is how the gnomologist understood the line. Finally,

, and this, perhaps, is how the gnomologist understood the line. Finally, ![]() (for

(for ![]() at Orest. 3 and

at Orest. 3 and ![]() (for

(for ![]() ) at Hipp. 1462, both deriving from confusion of two very similar compendia, show that at Hipp. 1260

) at Hipp. 1462, both deriving from confusion of two very similar compendia, show that at Hipp. 1260 ![]() , though seeming to be midway between the variants

, though seeming to be midway between the variants ![]() and

and ![]() , is nevertheless the virtual equivalent of

, is nevertheless the virtual equivalent of ![]() . [Turyn, , op. cit., p. 327Google Scholar, perhaps through inadvertence (but cf. ibid., p. 11 ad fin.), cites Gg as reading

. [Turyn, , op. cit., p. 327Google Scholar, perhaps through inadvertence (but cf. ibid., p. 11 ad fin.), cites Gg as reading ![]() here.]

here.]

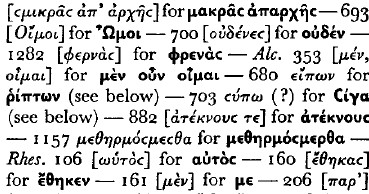

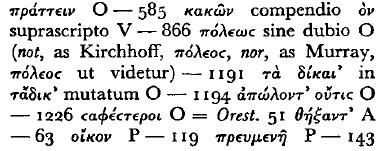

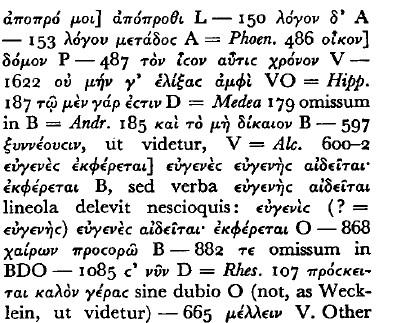

page 135 note 1 In spite of the pleas for re-collation (see p. 134, n. 3), the number of gross inaccuracies in the collations of Kirchhoff, Prinz, and Wecklein is not generally realized. I append a miscellaneous selection of manuscript readings noted in the course of this and other investigations: Hec. 282 ![]()

quite important manuscript variants are mentioned by Kirchhoff but not by Wecklein or Murray. Innumerable minor variants have been neglected by all previous collators (see p. 134, n. 2).

quite important manuscript variants are mentioned by Kirchhoff but not by Wecklein or Murray. Innumerable minor variants have been neglected by all previous collators (see p. 134, n. 2).

page 135 note 2 Mr. Skeat informs me that amongst extant Greek manuscripts there are few such pairs of exemplar and apograph deriving from so early a date. For this reason the writer intends to publish ebewhere a survey of some interesting features of scribal practice revealed by these collations.

page 135 note 3 The collations made at Vatopedi were completed in circumstances not dissimilar to those described, in picturesque detail, by Miller, , op. cit., pp. 501–2.Google Scholar

page 136 note 1 Cf. Schenkl, , op. cit., p. 310: ‘Non pauca ut loci communes efficerentur immutata omissa addita esse invenies.’Google Scholar