Article contents

A Fragment of the Arimaspea

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

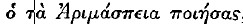

The longest extant fragment of the Arimaspea consists of six lines quoted by ‘Longinus’ in On the Sublime 10. 4. He does not mention its author by name but contents himself with a guarded reference to 6  , as if he himself had doubts about the authenticity of its ascription to Aristeas of Proconnesus.

, as if he himself had doubts about the authenticity of its ascription to Aristeas of Proconnesus.

- Type

- Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1956

References

page 1 note 1 Alföldi, A., Gnomon, ix (1933), 517 ff.,Google Scholar shows that the one-eyed Arimaspians and lie gold-guarding griffins are genuine crea tes of Asiatic folk-lore. If so, stories of them may have penetrated into Greek lands long before Aristeas, since the late Mycenaean ivory mirror-handle from Enkomi in Cyprus (Lorimer, H. L., Homer and the Monuments, Pl. II, 4)Google Scholar shows a warrior, who is not, how-ever, one-eyed, fighting a griffin.

page 1 note 2 Alcman also refers to them (fr. 59 Diehl), uid, since he is known to have been interested in fabulous peoples (Strab. 1. 43; Aristid. 2. 508), it is tempting to think that he too drew upon Aristeas. But no certainty is possible owing to our lack of firm information about both poets' dates. If with Wade-Gery, H. T., The Poet of the Iliad, 75,Google Scholar we put Aristeas at the earliest in the second quarter of the seventh century, and with Page, D. L., Alcman; the Partheneion, 166,Google Scholar Alcman in the middle, it is possible that some influence took place.

page 2 note 1 Chadwick, N. K., J.R.A.I. lxvi (1936), 313–16;Google ScholarDodds, E. R., The Greeks and the Irrational, 162.Google Scholar

page 2 note 2 For Greek shamanism in general, and for Aristeas' relation to the beliefs of his age, cf. Dodds, , op. cit. 135–78.Google Scholar

page 3 note 1 Schmid-Stahlin, , Griech. Lit.-Gesch. i. 303.Google Scholar

page 3 note 2 Bethe, E., in P.-W., R.-E. ii. 877.Google Scholar

page 3 note 3 Lesky, A., Thalatta, 110 ff.Google Scholar

page 3 note 4 Pliny, , N.H. 7. 2. 23:Google Scholar ‘idem hominum genus qui Monocoli vocentur singulis cruribus, mirae pernicitatis ad sal turn; eosdem Sciapodas vocari, quod in maiore aestu humi iacentes resupini umbra se pedum protegant.’ Hecataeus (17 F 327 Jacoby) puts them in Aethiopia. Cf. also Aristoph. Av. 1553; Scylax ap. Philostrat. Vit. Ap. 3. 47. As we know nothing about the ![]() , there is no good reason for identifying them with the

, there is no good reason for identifying them with the ![]() or even for assuming that they are the same kind of creature. If Alcman used two different names, he probably implied two different kinds of creature.

or even for assuming that they are the same kind of creature. If Alcman used two different names, he probably implied two different kinds of creature.

page 4 note 1 Longinus on the Sublime, p. 218.

page 6 note 1 If Blakeway, A. A., Greek Poetry and Life, pp. 34–55,Google Scholar is right in putting Archilochus at the time of the Lelantine War c. 700 B.C., there is no difficulty in assuming that Aristeas knew this line of his. But a strong case for c. 650 has been argued by Jacoby, F.C.Q. xxxv (1941), 97–109,CrossRefGoogle Scholar and that would probably rule out any connexion.

page 8 note 1 Professor A. Andrewes points out to me that ![]() may suggest that the speakers have other things to mention which they find peculiar in ways of life not their own and that perhaps, while Aristeas expresses his amazement at what they say about their neighbours, they retort that a lot of reported Greek activities seem improbable to them.

may suggest that the speakers have other things to mention which they find peculiar in ways of life not their own and that perhaps, while Aristeas expresses his amazement at what they say about their neighbours, they retort that a lot of reported Greek activities seem improbable to them.

page 9 note 1 It is tempting to surmise that Herodotus' account of Kolaxais, the ancestor of the Scythian kings (4. 5), comes from Aristeas, since, if Alcman indeed knew the Arimaspea, his otherwise obscure reference to a ![]()

![]() (fr. 1. 59 Diehl), which D. L. Page, op. cit. 90, thinks must apply to an illustrious breed of horses ‘familiar to Alcman's audience’, would then be a simple literary reference from a work which had recently come into circulation.

(fr. 1. 59 Diehl), which D. L. Page, op. cit. 90, thinks must apply to an illustrious breed of horses ‘familiar to Alcman's audience’, would then be a simple literary reference from a work which had recently come into circulation.

- 1

- Cited by