Article contents

An argument in Metaphysics Z 13

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

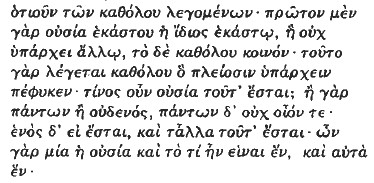

In Metaphysics Z 13 Aristotle argues that no universal can be substance. Prima facie, this appears to rule out the possibility that any universal can be substance, species as well as genera. Nevertheless, many commentators have denied that this chapter intends to rule out the possibility that any universal can be substantial. Aristotle, it is thought, cannot wish to deny that any universal can be substance because he believes that some universals are substances, viz. species.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1980

References

1 Woods, Michael, ‘Problems in Metaphysics Z, Chapter 13’, in Moravcsik, J. (ed.), Aristotle (New York, 1967), p. 216;Google ScholarAlbritton, R., ‘Forms of Particular Substances in Aristotle’s Metaphysics’, Journal of Philosophy, 54 (1957), 705;CrossRefGoogle ScholarMoreau, J., ‘Sein und Wesen in der Philosophic des Aristoteles’, in Hager, Fritz-Peter (ed.), Metaphysik und Theologie des Aristoteles (Darmstadt, 1969), p. 231;Google ScholarWerner, C., Aristote et l'idéalisme platonicien (Paris, 1910), p. 66Google Scholar n. 1, and La Philosophic grecque (Paris, 1972), p. 118;Google ScholarHicks, R. D., Aristotle: De Anima (Cambridge, 1907), p. 187;Google ScholarHartmann, N., ‘Aristoteles und das Problem der Begriffs’, in Kleinere Schriften ii (Berlin, 1957), 106,Google Scholar and ‘Zur Lehre vom Eidos bei Platon und Aristoteles’, ibid. 137; Chen, Chung-Hwan, Sophia (New York, 1976), p. 576Google Scholar n. 22; cf. Gohlke, P., Die Lehre von der Abstraktion hei Plato und Aristoteles (Halle, n.d.), p. 96;Google Scholar C. Arpe, Das ![]() bei Aristoteles (Hamburg, 1938), p. 45 n. 67;Google ScholarMoreau, J., Aristote et son école (Paris, 1962), pp. 148–9;Google ScholarRorty, R., ‘Genus as Matter’, in Lee, , Mourelatos, , Rorty, (eds.), Exegesis and Argument (Assen, 1980), p. 413.Google Scholar

bei Aristoteles (Hamburg, 1938), p. 45 n. 67;Google ScholarMoreau, J., Aristote et son école (Paris, 1962), pp. 148–9;Google ScholarRorty, R., ‘Genus as Matter’, in Lee, , Mourelatos, , Rorty, (eds.), Exegesis and Argument (Assen, 1980), p. 413.Google Scholar

2 ![]()

Many of my translations in this paper are based on W. D. Ross’s translation of the Metaphysics.

3 Aristotle's Metaphysics, ii (Oxford, 1924), 210.Google Scholar

4 Problems in Metaphysics Z, Chapter 13, op. cit., pp. 217–19.Google Scholar

5 Robin, L. seems to suggest something like this, in La Théorie platonicienne des Idées et des Nombres d’après Aristote (Paris, 1908), p. 36.Google Scholar Also cf. Grote, G., Aristotle, ii (London, 1872), 342–3.Google Scholar

6 Although Cherniss, H. F. (Aristotle's Criticism of Plato and the Academy (New York, 1962), p. 318Google Scholar n. 220) construes the premiss ‘those things whose substance and essence are one are themselves one’ (14) as providing a ground, not for the conclusion that b and c are identical with a (13–14), but for saying that F must be the substance of all of a, b, and c or none of them (12–13), ‘it is hard not to take 11.14–15 ![]()

![]() as providing a reason for what is asserted immediately before, especially as it is readily intelligible as a reason for it.’ (Woods, Michael, ‘Problems in Metaphysics Z, Chapter 13’, op cit., p. 219). And that premiss is used for the same conclusion in at least two other places in the Metaphysics (999b21–2, 1040b17). See below.Google Scholar

as providing a reason for what is asserted immediately before, especially as it is readily intelligible as a reason for it.’ (Woods, Michael, ‘Problems in Metaphysics Z, Chapter 13’, op cit., p. 219). And that premiss is used for the same conclusion in at least two other places in the Metaphysics (999b21–2, 1040b17). See below.Google Scholar

7 On the use of this example in the argument see Cherniss, , ACPA, op. cit., p. 320 n. 223. It is also possible, however, that Aristotle is using the term ‘man’ and ‘horse’ in 18 to refer to the souls of a man and a horse (cf. 1043a36–b4, 1033a29, b17–18, 1035a6–9, bl–3, 1036a16–17, 1037a7–8, De Caelo 278a13–15, De Gen. et Corr. 321b19–22), which he certainly does consider to be essences (1017b14–16, 21–3, 1035b14–16, 1037a22–9, 1043b2–4, De Anima 412b10–17).Google Scholar

8 ‘Forms of Particulars in Aristotle's Metaphysics’, op. cit., p. 705.Google Scholar Cf. Syranius' reply to Aristotle's argument in Asclepius' commentary (In Metaphysicorum Libros A–Z Commentaria, ed. Hayduck, M. (Berlin, 1888), 433. 26–30.Google Scholar

9 It is so understood by -Alexander, Ps. (In Aristotelis Metaphysial Commentaria, ed. Hayduck, M. (Berlin, 1891), 523–4,CrossRefGoogle ScholarAsclepius, , op. cit. 430 and Syranius, in Asclepius, 433.Google Scholar

10 ‘Forms of Particulars in Aristotle's Metaphysics’, op. cit., 705.Google Scholar

11 ‘Problems in Metaphysics Z, Chapter 13’, op. cit., p. 224.Google Scholar Cf. 999a4: ![]()

![]() and 1059a36–7, 1016b24–7, Top. 103a10–14.

and 1059a36–7, 1016b24–7, Top. 103a10–14.

12 Cf. -Alexander, Ps., 366, 30–1.Google Scholar

13 This is confirmed by 1053b16–21.

14 ‘Forms of Particular Substances in Aristotle's Metaphysics’, op. cit., p. 705.Google Scholar

15 Ibid.

16 ‘Problems in Metaphysics Z, Chapter 13’, op. cit., p. 235.Google Scholar

17 Ross’s text. Jaeger brackets ![]()

![]() and does not accept Ross's addition of

and does not accept Ross's addition of ![]() after

after ![]() in 1087al. But even if he is right, that the resulting sentence, when left intact, expresses a view that Aristotle would assent to is shown by 1087a21–2 (quoted below, p. 83).

in 1087al. But even if he is right, that the resulting sentence, when left intact, expresses a view that Aristotle would assent to is shown by 1087a21–2 (quoted below, p. 83).

18 On Ross's account 999b24–7 presents only one argument against the suggestion that the principles of things are one in form: ‘The argument may be paraphrased thus: If a principle discovered by analysis of one thing can only be one in kind with a principle discovered by analysis of another thing, no two things will ever have a numerically identical principle; but if there is not this, if there is not a ![]() how is knowledge possible?' (Aristotle's Metaphysics, op. cit. i. 242).Google Scholar That this is not correct can be seen from the fact that Ross presupposes that things are one in number, whereas Aristotle says that this is ruled out by the hypothesis that the principles are one in form only. Furthermore, the conclusion that nothing is one in number is absurd, and is an absurdity distinct from the conclusion that knowledge will not be possible. Thus in M 10, the conclusion that all things are universals is considered absurd in itself (1086b37–1087a2, 21–4). and there it is certain that no epistemological considerations are in question.

how is knowledge possible?' (Aristotle's Metaphysics, op. cit. i. 242).Google Scholar That this is not correct can be seen from the fact that Ross presupposes that things are one in number, whereas Aristotle says that this is ruled out by the hypothesis that the principles are one in form only. Furthermore, the conclusion that nothing is one in number is absurd, and is an absurdity distinct from the conclusion that knowledge will not be possible. Thus in M 10, the conclusion that all things are universals is considered absurd in itself (1086b37–1087a2, 21–4). and there it is certain that no epistemological considerations are in question.

Ernst Tugendhat does no better. He glosses 999 24–7: ‘Sind die eidetischen ![]() hingegen

hingegen ![]() so sind sie als

so sind sie als ![]() des Einzelnen selbst je einzelnen, aber untereinander gleich. Doch “wie ist dann ein Wissen möglich” fragt Aristoteles 999b27 “wenn es nicht ein Eines über den Vielen

des Einzelnen selbst je einzelnen, aber untereinander gleich. Doch “wie ist dann ein Wissen möglich” fragt Aristoteles 999b27 “wenn es nicht ein Eines über den Vielen ![]() gibt?”’ (TI KATA TINO∑) (Freiburg, 1968), pp. 103–4).Google Scholar Like Ross, Tugendhat fails to see that there are two difficulties here, not one. Nor does Aristotle's hypothesis that the principles are one in form allow that they are one in number. What Aristotle says is that if the principles are one in form

gibt?”’ (TI KATA TINO∑) (Freiburg, 1968), pp. 103–4).Google Scholar Like Ross, Tugendhat fails to see that there are two difficulties here, not one. Nor does Aristotle's hypothesis that the principles are one in form allow that they are one in number. What Aristotle says is that if the principles are one in form ![]()

19 Thus Joseph Owens (The Doctrine of Being in the Aristotelian Metaphysics (Toronto, 1963), p. 245)Google Scholar is mistaken in saying that the point of the aporia is that ‘the two types of unity seem incompatible in the same principles.’ Significantly, he quotes 999b24–1000a4 but omits b28–31 where Aristotle points out precisely that the difficulty in the thesis that the principles are one in number arises just in case the principles are one in number only and not also one in form. Similarly, the thesis that the principles are one in form must be the thesis that the principles are one in form only since otherwise the conclusion that ![]() would too obviously fail to follow. And as I try to show below, Aristotle does accept this argument.

would too obviously fail to follow. And as I try to show below, Aristotle does accept this argument.

Owens also misdescribes the arguments of the aporia. On 999b24–7 he says: ‘If the unity in the principles sought by Wisdom is specific, nothing will be singular, not even the highest so-called genera, Being and the “one”. But then there can be no scientific knowledge; for scientific knowledge requires a specific unity in singulars’ (246). What Aristotle says is that if nothing is one in number, ![]()

![]() Clearly it is the

Clearly it is the ![]() in the

in the ![]() which is assumed must be

which is assumed must be ![]() if there is to be knowledge. (He is assuming the Platonic view that the object of knowledge must be one in number. Cf. 1002b12–17, 22–5, and Cherniss, , ACPA, op. cit., pp. 221–2).Google Scholar He is not making the point that each of

if there is to be knowledge. (He is assuming the Platonic view that the object of knowledge must be one in number. Cf. 1002b12–17, 22–5, and Cherniss, , ACPA, op. cit., pp. 221–2).Google Scholar He is not making the point that each of ![]() must be one in number.

must be one in number.

Owens continues: ‘On the other hand, if each of the principles is numerically one and so not an instances of a species, there will be nothing apart from it. A species in this case would be a principle prior to the first principles. No scientific knowledge of such individual principles would be possible’ (ibid.). In fact, in the passage in question (999b27–1000a4) Aristotle neither says nor implies anything about species or knowledge. And of course it is not the thesis under examination – that the principles are one in number – which in 999b24–1000a4 is said to lead to the conclusion that knowledge is not possible but rather the first hypothesis that the principles are one in form.

20 Cf. Physics 187b10–ll: ![]()

![]()

![]() (cf. 996a1, 1002b 17–19, 22–5, Phys. 189a12–13). Aristotle's solution to the aporia is that although unlimited in number, the principles are not unlimited in kind.

(cf. 996a1, 1002b 17–19, 22–5, Phys. 189a12–13). Aristotle's solution to the aporia is that although unlimited in number, the principles are not unlimited in kind.

21 Aristotle begins the chapter by stating that the aporia to be discussed has already been pointed out in B. A comparison of 999b27–33 with 1086b20–32 should suffice to show that 999b24–1000a14 is at least part of what he is referring to in B. (Cf. Robin, , La Théorie platoniccienne, op. cit., p. 529 n. 478).Google Scholar There is no warrant for Ross's claim that the question in 999b24– 1000a4 is ‘the same question’ as that raised in Z 14 (Aristotle's Metaphysics, op. cit., i. 242).Google Scholar Nor, as he claims, is A 4 or 5 relevant since there the question is whether the principles are the same by analogy and this is distinct from the question whether they are the same in number or the same in form.

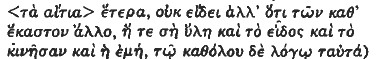

22 Syllables are used as analogues of substances, and the ![]() of syllables as analogues of the principles of substances. The view expressed in this passage is presupposed in 1074a31–3. Cf. 1071a23, De Caelo 278a18–20.

of syllables as analogues of the principles of substances. The view expressed in this passage is presupposed in 1074a31–3. Cf. 1071a23, De Caelo 278a18–20.

23 ‘Problems in Metaphysics Z, Chapter 13’, op. cit., p. 219.Google Scholar

24 Ibid., p. 230.

25 995b29–31, 998b15–16, 999a4–6, 15, 1006b14, 1007a33–4, b16, 1035a7–8, bl–3, 27–8, 1054a16–17, 1088a8–13; E. N. 1147a 4–5; Top. 121b3–4, 11–14; An. Post. 83a24– 5,b; De Int. 20b34, 37–8, 21a18–20, bl; Parva Nat. 467b21–2.

26 1006a33, b19–20, 21–2, 29, 33–4, 1007a10–ll, 12, 16, 17, b20–l, 24, 33, 1008a4, b19, 23–4, 1015b31–3, 1022a34–5, 1028a15–18, 1041a17–18, 22, 1062a27, 29–30, 1087a21; E. N. 1135a29, 1147a6; Top. 103b29–30, 125b39; An. Pr. 43a25–32; An. Post. 73a30; De Int. 21a2–3, 19–20; De Motu Anim. 701a13–15, 27; Phys. 224a15; Parva Nat. 458b14; De Gen. Anim. 767b30–l.

27 There appears to be no reason to accept Ps.-Alexander's reading ![]() Cf. Ross, , Aristotle's Metaphysics, op. cit. ii,Google Scholar ad. loc.; Robin, , La Théorie platonicienne, op. cit., p. 531 n. 480.Google Scholar

Cf. Ross, , Aristotle's Metaphysics, op. cit. ii,Google Scholar ad. loc.; Robin, , La Théorie platonicienne, op. cit., p. 531 n. 480.Google Scholar

28 Another passage where the difference between the universal form and the individual form emerges is 1074a31–5: ‘For if there are many heavens as there are many men, the principle of each will be one in form but many in number. But those things which are many in number have matter (for one and the same definition is of many, but Socrates is one).’ There is one definition of the universal, but the principles of individual men are themselves individuals. This is what Aristotle argues in A 5 (1070a20–l): ![]()

![]()

James Lesher's contention that Aristotle's substantial forms are universals rests on his confusion of the universal form with the individual substantial form (“Aristotle on Form, Substance and Universals: A Dilemma’, Phronesis, 16 (1971), 174–6).Google Scholar Commenting on a passage from A 5 (1071a 27–9: ![]()

Lesher says: ‘Aristotle explicitly says here that the universal definition of each of our forms is the same … Thus Albritton cannot conclude from this that the form is not a universal…’ The definition defines the universal form, but it doesn't follow that your form and mine are not numerically different. As Aristotle says (1016a36):

Lesher says: ‘Aristotle explicitly says here that the universal definition of each of our forms is the same … Thus Albritton cannot conclude from this that the form is not a universal…’ The definition defines the universal form, but it doesn't follow that your form and mine are not numerically different. As Aristotle says (1016a36): ![]()

![]()

![]() For example, your form and mine.

For example, your form and mine.

I would like to thank Professor David Furley, Professor G. E. L. Owen, and Professor Michael Frede for having read and commented on earlier drafts of this paper.

- 1

- Cited by