Article contents

The Watchman Scenes in the Antigone

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

Probably no Greek tragedy has proved as rich a source of perplexity, theory, and debate as the Antigone. A number of the formidable problems which various critics have seen in the play emerge from the two watchman scenes and the great ode which separates them. It will be argued here that these difficulties are the result of certain radical misunderstandings and are capable of straightforward solution.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1962

References

page 202 note 1 Minor contradictions were grist to the mill of Wilamowitz's theory. To support the existence of this one he used a subtle argument. Quoting Septem 1039 ![]()

![]() (‘die Erde nämlich’), he suggested that this absurd detail was put in because the interpolator wanted to explain the difficulty which he had recognized in Sophocles' description. To this there are two objections: it is by no means certain that Aeschylus was not the author of the final section of the Septem (see Lloyd-Jones, H. in C.Q. N.S. ix [1959], 80–115)CrossRefGoogle Scholar and Wilamowitz's interpretation of 1039, though based on the scholium, is almost incredible Greek as well as preposterous sense.

(‘die Erde nämlich’), he suggested that this absurd detail was put in because the interpolator wanted to explain the difficulty which he had recognized in Sophocles' description. To this there are two objections: it is by no means certain that Aeschylus was not the author of the final section of the Septem (see Lloyd-Jones, H. in C.Q. N.S. ix [1959], 80–115)CrossRefGoogle Scholar and Wilamowitz's interpretation of 1039, though based on the scholium, is almost incredible Greek as well as preposterous sense.

page 203 note 1 I assume that the watchmen are to be thought of as keeping guard in a group, but the scholium on 260 speaks of them watching ![]() and the phrase

and the phrase ![]()

![]() (253) might lend support to this view. But the detail has no dramatic significance.

(253) might lend support to this view. But the detail has no dramatic significance.

page 204 note 1 Wilamowitz, (op. cit., pp. 28–29)Google Scholar made use of the alleged effectiveness of the layer of dust to prove that Antigone's burial was a real and not merely symbolic rite. It is not clear whether he himself was unacquainted with the biological facts or only supposed Sophocles to be ignorant or careless of them. In any case his argument is irrelevant because, as Pohlenz points out (Erläuterungen, p. 82), religious belief made no distinction between symbolic and actual burial.Google Scholar

page 205 note 1 This is indeed how it was rendered by T. Johnson in his translation of 1708. ‘Multa quidem solertia, nihil vero Homine solertius est.’ He translates ![]() (344) by ‘vir praeditus solertia’ and

(344) by ‘vir praeditus solertia’ and ![]() (360) by ‘ad omnia ingeniosus’. Cf. Camerarius: ‘Chori carmen ingenium humanum praedicat, neque quicquam homine dicit esse callidius, nee item audacius, perque fas et nefas ruere in omnia.’

(360) by ‘ad omnia ingeniosus’. Cf. Camerarius: ‘Chori carmen ingenium humanum praedicat, neque quicquam homine dicit esse callidius, nee item audacius, perque fas et nefas ruere in omnia.’

page 206 note 1 T. Francklin (1759), who appears to have set the fashion for not seeing the connexion of this ode with the subject of the drama, dismissed Brumoy's explanation thus: ‘Surely the refinement of French criticism is required to discover an allusion so distant.’ But cf. Camerarius (1556): ‘Inter haec autem re- spiciunt ad sepultum clam custodibus Polynicen.’

page 207 note 1 Those who find it strange that Sophocles does not explain why Antigone wants to return with libations would do well to observe that Herodotus, an author not usually reticent of detail, does not say why the mother of the dead thief wants the body recovered.

page 208 note 1 As burial and lamentation are often mentioned together, so also ![]() and

and ![]() regularly form a pair. In Cho. 430–4 tne climax of Clytemnestra's wickedness is the burial of her husband without lamentation.

regularly form a pair. In Cho. 430–4 tne climax of Clytemnestra's wickedness is the burial of her husband without lamentation.

page 209 note 1 Lucian was scoffing at this belief when he wrote of the dead: ![]()

![]()

![]() cf. Rohde, , Psyche, i. 243.Google Scholar It is true that libations appear to have been normally repeated for the first time on the third day after burial, but Sophocles had no more reason to be precise over this than to make Antigone wait till the third day after death to conduct the

cf. Rohde, , Psyche, i. 243.Google Scholar It is true that libations appear to have been normally repeated for the first time on the third day after burial, but Sophocles had no more reason to be precise over this than to make Antigone wait till the third day after death to conduct the ![]() . The tragedians were not bound by the rubrics of a national church.

. The tragedians were not bound by the rubrics of a national church.

page 209 note 2 Those of us who find it possible to pity Creon are, according to the elder Wilamowitz, exhibiting ‘moderne sentimentale Schwäche’ (Gr. Tr., p. 114).Google Scholar Though critics have become less willing to worship Antigone the ‘Märtyrerin’, sympathy for despots has not grown in the forty years since Wilamowitz wrote.

page 210 note 1 Cf. the fantastic defence of Oedipus and furious condemnation of the unfortunate Creon of the O.T. (Jebb's ‘good type of Scottish character’) by Wilamowitz, U. von in Hermes xxxiv (1899), 55–80.Google Scholar

page 210 note 2 The extreme view that Creon is the same man in all three Theban plays has little to commend it. See Peterkin, L. D. in C. Phil. xxiv (1929), 263–73,CrossRefGoogle Scholar and G. Méautis, Sophocle.

page 210 note 3 The comparison with the O.T. is striking: Oedipus accuses Teiresias of regicide as soon as he shows unwillingness to speak; Creon, after Teiresias has told him that his mistaken policy has brought pollution to the state, reluctantly accuses the seer of the common vice of his trade—venality.

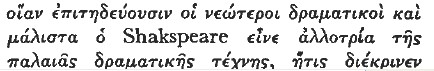

page 210 note 4 This raises the broader question whether comic characters were ever introduced in conventional tragedy, for the Watchman is perhaps the strongest candidate in the extant plays. I incline to the view succinctly expressed by D. C. Semitelos in his edition of 1887: ![]()

![]() (223 n.)

(223 n.)

page 211 note 1 I am deeply indebted to Mr. G. W. Bond, Mr. R. J. Norman, and Professor H. Lloyd–Jones, who read drafts of this paper and offered valuable criticism. I am of course entirely responsible for any faults which appear in the final version.

- 5

- Cited by