M. F. BURNYEAT

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

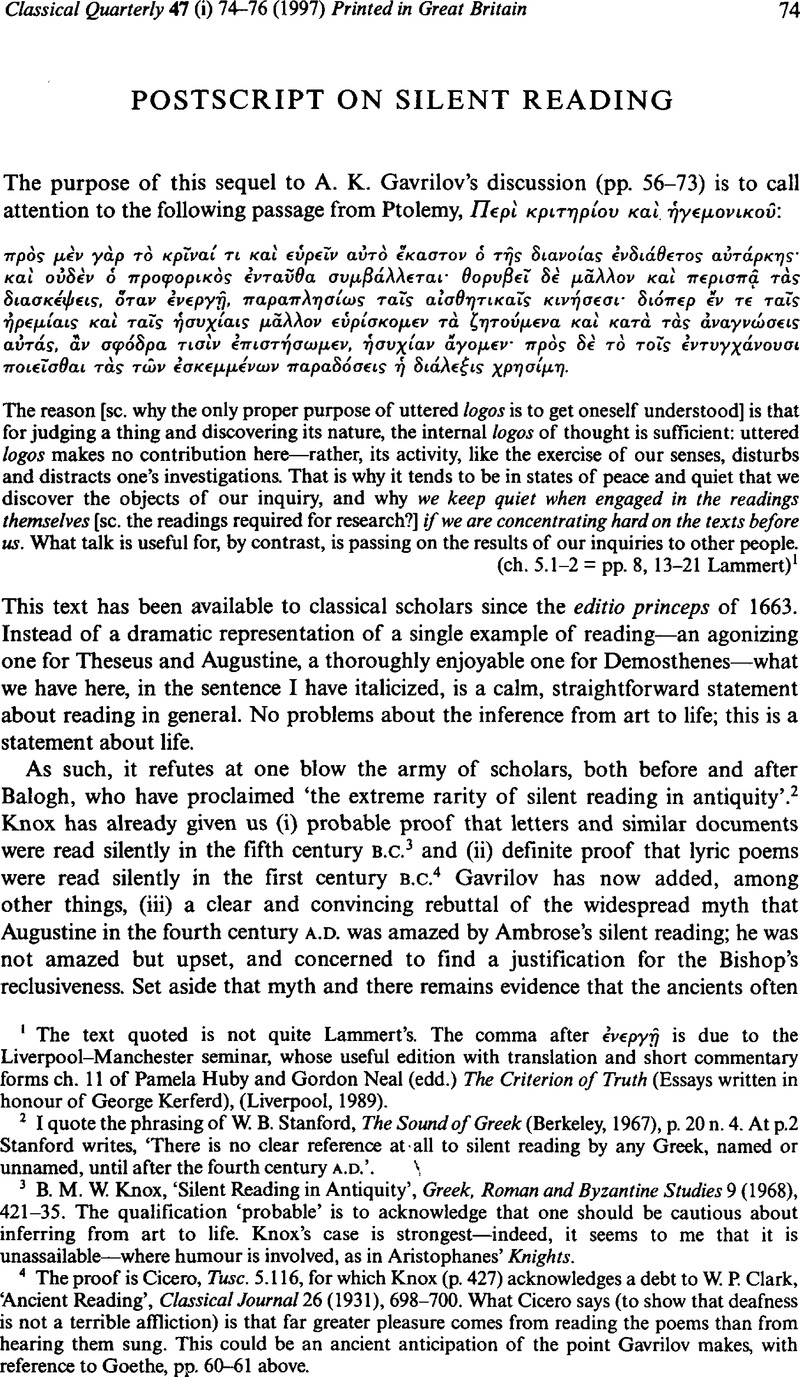

1 The text quoted is not quite Lammert's. The comma after ivepyrj is due to the Liverpool–Manchester seminar, whose useful edition with translation and short commentary forms ch. 11 of Pamela Huby and Gordon Neal (edd.) The Criterion of Truth (Essays written in honour of George Kerferd), (Liverpool, 1989).Google Scholar

2 I quote the phrasing ofGoogle ScholarStanford, W. B., The Sound of Greek (Berkeley, 1967), p. 20 n. 4. At p.2 Stanford writes, 'There is no clear reference at all to silent reading by any Greek, named or unnamed, until after the fourth century A.D.'.Google Scholar

3 Knox, B. M. W, ‘Silent Reading in Antiquity’, Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 9 (1968), 421–435. The qualification 'probable' is to acknowledge that one should be cautious about inferring from art to life. Knox's case is strongest–indeed, it seems to me that it is unassailable–where humour is involved, as in Aristophanes' KnightsGoogle Scholar

4 The proof is Cicero, Tusc. 5.116, for which Knox (p. 427) acknowledges a debt to Clark, W. P., ‘Ancient Reading’, Classical Journal Id (1931), 698–700. What Cicero says (to show that deafness is not a terrible affliction) is that far greater pleasure comes from reading the poems than from hearing them sung. This could be an ancient anticipation of the point Gavrilov makes, with reference to Goethe, pp. 60–61 above.Google Scholar

5 Cf. Hendrickson, G. L., ‘Ancient Reading’, The Classical Journal 25 (1929–1930), 186: 'By inference from many passages elsewhere we may conclude, as will appear, that ancient reading was habitually aloud; but no one else [sc. apart from Augustine], it would seem, has had occasion to comment on the strangeness of silent reading1 (italics mine).Google Scholar

6 It would be unwise to underestimate the economic aspect of such events. Exciting new books did not come out in a print–run of several thousand paperback copies for all to buy. Sharing books was a brute necessity–as it still is in many less privileged parts of the world today.

7 'Scriptio continua und anderes', Rheinisches Museum 67 (1912), 620, n. 1.Google Scholar

8 Balogh, J., ‘“Voces paginarum”: Beitrage zur Geschichte des Lauten Lesens und Screibens’, Philologus 82 (1927), 105 with n. 1, where Brinkmann is credited with bringing the passage to his notice.Google Scholar

9 Cf. p. 220, where Balogh admits that silent reading and writing are not unheard of, but claims to have shown that they are always the exception.

10 It deserves emphasis that the statement, besides being plain and straightforward in itself, comes from a work so boringly plain and straightforward that the most recent discussion sums it up as 'bland': A. A. Long, 'Ptolemy on the Criterion: an Epistemology for the Practising Scientist', in The Criterion of Truth, op. cit., p. 153. The tone and context of Ptolemy's remark ensure that modern scholars should treat it as the plainest of plain statements of fact.

11 N. 4 above.

12 For a sobering illustration, see Gilliard, Frank D., ‘More Silent Reading in Antiquity: Non omne verbum sonaf’, Journal of Biblical Literature 112 (1993), 689–96. He has to rebut the myth because Balogh has had more effect than Knox.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

13 Pace the comment ad loc. by Beutler, Rudolf and Theiler, Willy, Plotins Schriften Bd. V (Hamburg, 1960): 'Der Lesende: es ist offenbar noch an den Lautlesenden, Vorlesenden gedacht'. How could anyone but a zombie read aloud without being consciously aware and in control of their activity? The brusque confidence of this scholarly comment shows how powerful the myth can be.Google Scholar

14 I forbear from pressing the phrase ![]() at 98b 8.

at 98b 8.