No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

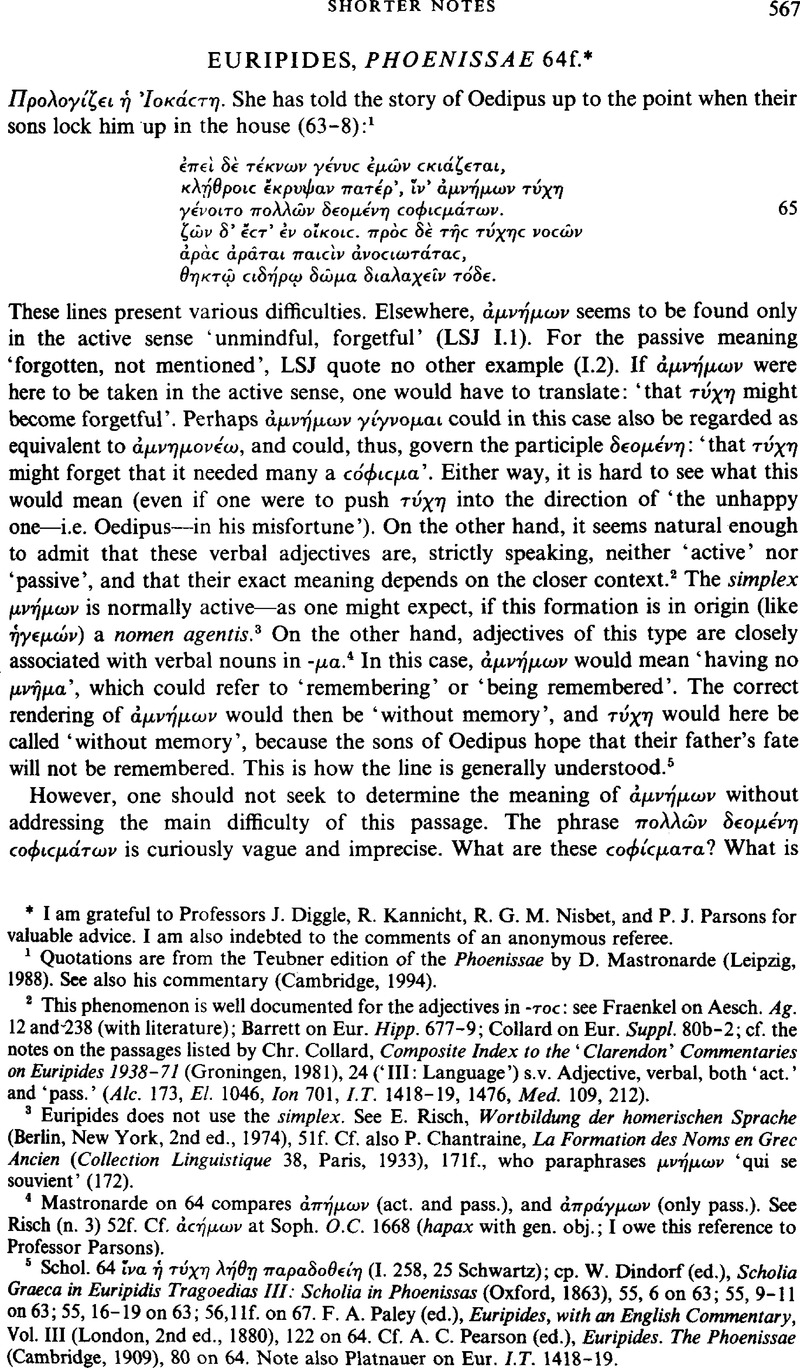

Euripides, Phoenissae 64f.–19

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Shorter Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1996

References

1 Quotations are from the Teubner edition of the Phoenissae by Mastronarde, D. (Leipzig, 1988). See also his commentary (Cambridge, 1994).Google Scholar

2 This phenomenon is well documented for the adjectives in -roc: see Fraenkel on Aesch.Ag. 12 and-238 (with literature); Barrett on Eur.Hipp. 677–9; Collard on Eur.Suppl. 80b–2; cf. the notes on the passages listed by Chr. Collard, Composite Index to the ‘Clarendon’ Commentaries on Euripides 1938–71 (Groningen, 1981), 24 (‘III: Language’) s.v. Adjective, verbal, both ‘act.’ and ‘pass.’ (Ale. 173, El. 1046, Ion 701, I.T. 1418–19, 1476, Med. 109, 212).

3 Euripides does not use the simplex. See Risch, E., Wortbildung der homerischen Sprache (Berlin, New York, 2nd ed., 1974), 51f. Cf. also P., Chantraine, La Formation des Noms en Grec Ancien (Collection Linguistique 38, Paris, 1933), 171f., who paraphrases ![]() ‘qui se souvient’ (172).Google Scholar

‘qui se souvient’ (172).Google Scholar

4 Mastronarde on 64 compares ![]() (act. and pass.), and

(act. and pass.), and ![]() (only pass.). See Risch (n. 3) 52f. Cf.

(only pass.). See Risch (n. 3) 52f. Cf.![]() at Soph. O.C. 1668 (hapax with gen. obj.; I owe this reference to Professor Parsons).

at Soph. O.C. 1668 (hapax with gen. obj.; I owe this reference to Professor Parsons).

5 Schol. 64 ![]() (I. 258, 25 Schwartz); cp.Dindorf, W. (ed.), Scholia Graeca in Euripidis Tragoedias III: Scholia in Phoenissas (Oxford 1863) 55, 6 on 63; 55, 9–11 on 63; 55, 16–19 on 63; 56,1 If. on 67.Paley, F. A. (ed.), Euripides, with an English Commentary, Vol.Ill (London, 2nd ed., 1880), 122 on 64. Cf. Pearson, A. C. (ed.), Euripides. The Phoenissae (Cambridge, 1909), 80 on 64. Note also Platnauer on Eur.I.T. 1418–19.Google Scholar

(I. 258, 25 Schwartz); cp.Dindorf, W. (ed.), Scholia Graeca in Euripidis Tragoedias III: Scholia in Phoenissas (Oxford 1863) 55, 6 on 63; 55, 9–11 on 63; 55, 16–19 on 63; 56,1 If. on 67.Paley, F. A. (ed.), Euripides, with an English Commentary, Vol.Ill (London, 2nd ed., 1880), 122 on 64. Cf. Pearson, A. C. (ed.), Euripides. The Phoenissae (Cambridge, 1909), 80 on 64. Note also Platnauer on Eur.I.T. 1418–19.Google Scholar

6 Mastronarde on 65: ‘requiring many clever shifts to be forgotten’ (quoting Heliod. 4. 6. 26 for the ellipse of sense). Paley (n. 5) 122 on 64: ‘The sense is, “that his fate might pass out of memory, requiring as it did many devices (for its concealment)”’.Powell, J. U. (ed.), The Phoenissae of Euripides (London, 1911), 151 on 64: ‘![]() “devices to conceal i t ” ’ .Chr., Mueller-Goldingen, Untersuchungen zu den PhÖnissen des Euripides (Palingenesia 22, Wiesbaden-Stuttgart, 1985), 47: ‘Es bedurfte vieler Kniffe, um dieses Schicksal in Vergessenheit geraten zu lassen.’E. Craik (ed.), Euripides. Phoenician Women (Warminster, 1988), 65 translates:‘ … they hid their father with barred doors, so that his fortune should be unmentioned, despite needing many devices to conceal it.’ Cf. also the translation by H. Grotius (quoted from L. C. Valckenaer's edition of the Phoenissae, 1755): iam barba postquam filios pinxit meos, / patrem coercent carcere, ut sortem tegant, / quae ne patescat artibus multis eget. / domi ille vivit, atque fortunae ad mala / diras tremendas in genus cumulat suum, / ut sanguinante dividant ferro domum. The referee points to Bacchae 30, where ‘Cadmus’ supposed attempt to disguise a human rape as a divine one is termed a

“devices to conceal i t ” ’ .Chr., Mueller-Goldingen, Untersuchungen zu den PhÖnissen des Euripides (Palingenesia 22, Wiesbaden-Stuttgart, 1985), 47: ‘Es bedurfte vieler Kniffe, um dieses Schicksal in Vergessenheit geraten zu lassen.’E. Craik (ed.), Euripides. Phoenician Women (Warminster, 1988), 65 translates:‘ … they hid their father with barred doors, so that his fortune should be unmentioned, despite needing many devices to conceal it.’ Cf. also the translation by H. Grotius (quoted from L. C. Valckenaer's edition of the Phoenissae, 1755): iam barba postquam filios pinxit meos, / patrem coercent carcere, ut sortem tegant, / quae ne patescat artibus multis eget. / domi ille vivit, atque fortunae ad mala / diras tremendas in genus cumulat suum, / ut sanguinante dividant ferro domum. The referee points to Bacchae 30, where ‘Cadmus’ supposed attempt to disguise a human rape as a divine one is termed a ![]() .Google Scholar

.Google Scholar

7 Cf., e.g., Wecklein, N. (ed.), Euripidis Phoenissae (Leipzig, 2nd ed., 1881), 22 on 65: ‘“Quae multis indiget artibus ad excusandum” i.e. quae aegre excusari potest. Scilicet purgat mater filios’;N. Wecklein (ed.), Ausgewdhlte Tragdien des Euripides V: Phonissen (Leipzig, 1894), 35 on 64f:‘schwer zu beschonigen’ (E., Fraenkel in the margin of his copy, kept in the Ashmolean Library: ‘Nein: “schwer zu verheimlichen”’). The referee: ‘“ so that ![]() might become forgotten because it needed a good deal of cleverness (to explain it) or (to handle its consequences)”’ (comparing 472; 871; 1259).Google Scholar

might become forgotten because it needed a good deal of cleverness (to explain it) or (to handle its consequences)”’ (comparing 472; 871; 1259).Google Scholar

8 Cycl. Theb. fr.2 Bernabe or Davies (Eustathius is quoted ad /.). As ![]() shows, this is Eustathius' own interpretation of the fragment. Welcker and Bethe thought that he was right (E., Bethe, Thebanische Heldenlieder. Untersuchungen iiber die Epen des thebanisch-argivischen Sagenkreises [Leipzig, 1891], 103 with note 40). Cf. below, n. 13, on Oedipus' curse(s).Google Scholar

shows, this is Eustathius' own interpretation of the fragment. Welcker and Bethe thought that he was right (E., Bethe, Thebanische Heldenlieder. Untersuchungen iiber die Epen des thebanisch-argivischen Sagenkreises [Leipzig, 1891], 103 with note 40). Cf. below, n. 13, on Oedipus' curse(s).Google Scholar

9 Cf. Mastronarde on 65. The same effect is achieved by Geelius, J. (ed.), Euripidis Phoenissae (Leiden, 1846), who conjectures ![]() (85f adl.; attributed to ‘Zakas 1891’ by Mastronarde in his appendix coniecturarum, 128): ‘Suspicor duplicem Scholiastae interpretationem admitti non posse, sed corrigendum esse

(85f adl.; attributed to ‘Zakas 1891’ by Mastronarde in his appendix coniecturarum, 128): ‘Suspicor duplicem Scholiastae interpretationem admitti non posse, sed corrigendum esse ![]() . Ipsa occlusio Oedipi erat

. Ipsa occlusio Oedipi erat ![]() . Potuerunt sane reliqua

. Potuerunt sane reliqua ![]() in Cyclica Thebaide commemorari, ut Poeta eo respicere videatur; sed

in Cyclica Thebaide commemorari, ut Poeta eo respicere videatur; sed ![]() refertur ad

refertur ad ![]() , ut 475.

, ut 475.![]() , non ad praedicatum

, non ad praedicatum ![]() : itaque sententia non accurate enuntiata est: substituto

: itaque sententia non accurate enuntiata est: substituto ![]() , interpreter:patrem occultum tenuerunl, multos modos excogitantes, quibus calamitatem eius ab hominum notitia removerent. Sed urgere hoc nolim.’ The final clause can hardly depend on the participle, and to read the

, interpreter:patrem occultum tenuerunl, multos modos excogitantes, quibus calamitatem eius ab hominum notitia removerent. Sed urgere hoc nolim.’ The final clause can hardly depend on the participle, and to read the ![]() as a reference to the Thebaid seems as arbitrary (or desperate) as C., Robert's Callimachean verismo (Oidipus. Geschichte eines poetischen Stoffes im griechischen Altertum [Berlin, 1915], vol.I, p.173): ‘Um den vielfachen Fragen nach dem Befinden und dem Aufenthalt ihres Vaters zu begegnen, haben Eteokles und Polyneikes den Thebanern gegeniiber viele Ausreden notig’ (cf. Call.h. 6. 72–86).Google Scholar

as a reference to the Thebaid seems as arbitrary (or desperate) as C., Robert's Callimachean verismo (Oidipus. Geschichte eines poetischen Stoffes im griechischen Altertum [Berlin, 1915], vol.I, p.173): ‘Um den vielfachen Fragen nach dem Befinden und dem Aufenthalt ihres Vaters zu begegnen, haben Eteokles und Polyneikes den Thebanern gegeniiber viele Ausreden notig’ (cf. Call.h. 6. 72–86).Google Scholar

10 This is the view which Pearson adopts in the end.Cf.Wecklein 1881 (n.7), 22 on 66: ‘I.e. quamquam Fortuna ei causa malorum est, non filii qui includentes patrem necessitati paruerunt’ (cf. ibid., on 65); Wecklein 1894 (n. 7), 35 on 66ff.:‘… obwohl die Schuld an seinem Wehe dem Schicksal zufiel, nicht den Söhnen’; schol. 67:![]()

![]() (111.56, 9f. Dindorf).

(111.56, 9f. Dindorf).

11 Cf.Mastronarde on 66. Paley (n. 5) 122 on 66: ‘While other writers, following the account in the Cyclic poems, made Oedipus curse his sons because he had been badly fed by them (![]() , Aesch.Theb. 783), Euripides has here preferred to describe him simply as “maddened by his fortune”, or by the circumstances of his position.’ Craik (n. 6) translates ‘deranged from ill-fortune’ (65), but comments (172 on 66–8): ‘Iokaste glosses over…the reason for Oidipous' curse on his sons, blaming neither him nor them’ (cp. ibid., on 64–5). On the contrary, she clearly condemns Oedipus' curses as

, Aesch.Theb. 783), Euripides has here preferred to describe him simply as “maddened by his fortune”, or by the circumstances of his position.’ Craik (n. 6) translates ‘deranged from ill-fortune’ (65), but comments (172 on 66–8): ‘Iokaste glosses over…the reason for Oidipous' curse on his sons, blaming neither him nor them’ (cp. ibid., on 64–5). On the contrary, she clearly condemns Oedipus' curses as ![]() , nor is there any trace of her palliating her sons' deed.

, nor is there any trace of her palliating her sons' deed.

12 Thus Mastronarde on 66: ‘![]() ; = specifically “what had just happened to him”’. Robert (n. 9) 1.177 on 66f.:‘ Hier wird also als das Motiv seines Zornes und seiner Gemiitsstorung schon die bloBe Gefangenhaltung hingestellt.’ Cf. schol. 66:

; = specifically “what had just happened to him”’. Robert (n. 9) 1.177 on 66f.:‘ Hier wird also als das Motiv seines Zornes und seiner Gemiitsstorung schon die bloBe Gefangenhaltung hingestellt.’ Cf. schol. 66:![]()

![]() (111.55,26–56,1 Dindorf; cf. 56,10–4 on 67).

(111.55,26–56,1 Dindorf; cf. 56,10–4 on 67).

13 See Bethe (n. 8) 102–6; Robert (n. 9) 1.67. 109. 169–80. 263f. 353f. 466–71;Hutchinson G. O. (ed.), Aeschylus. Septem contra Thebas (Oxford 1985), xxvf. Cf. frr.2 and 3 of the Cyclic Thebaid (literature in Bernabéad I.);TrGF adesp. 346b, and 458.

14 Teiresias is speaking about Oedipus' sons:![]()

![]()

![]()

15 869–80 were deleted by E., Fraenkel, Zu den Phoenissen des Euripides (SB Miinchen, 1963/1901), 37–43.Google Scholar For a defence of the passage, see H., Diller's review of Fraenkel, Gnomon 36 (1964), 641–50,Google Scholar at 647, and H., Erbse, ‘Beitrage zum Verstandnis der Euripideischen Phoinissen’, Philologus 110 (1966), 1–34,Google Scholar at 9–13. Cf.Reeve, M. D., ‘Interpolation in Greek Tragedy I’, GRBS 13 (1972), 247–65 (reviewing J. Baumert, ENIOI AΘETOγΣIN [Diss. Tubingen, 1968]); ‘Interpolation in Greek Tragedy II’, GRBS 13 (1972), 451–74 (against Erbse's article); ‘Interpolation in Greek Tragedy HI’, GRBS 14 (1973), 145–71 (he does not discuss 869–80 in detail, but see pp. 458f. of the second article).Google Scholar

16 See Jackson, J., Marginalia Scaenica (Oxford, 1955), 220–2:Google Scholar ‘Unconscious Repetitions by the Poet’; cf. 198f.; 223–7: ‘Unconscious Repetitions by the Copyist’;Page, D. L., Actors' Interpolations in Greek Tragedy (Oxford, 1934), 122f.; cf. 127f.; 145.Google Scholar

17 Mastronarde notes in the app. crit. that 65 is omitted in Laurentianus 32.33 ante correctionem; but since it was added between the lines, this looks like a chance omission, not like independent testimony (see Mastronarde, D. J.Bremer, J. M., The Textual Tradition of Euripides' Phoinissai[University of California Publications. Classical Studies 27, Berkeley, Los Angeles, 1982], 194 on 65:Google Scholar ‘versum om., deinde inter lineas add. Rf’). Neither Wecklein, in the app. crit. or the appendix coniecturas minusprobabiles continens of his edition (Euripidis Fabulae, Prinz, R.N., Wecklein [eds.], III.4, Leipzig, 1901), nor Mastronarde, in app. crit., appendix coniecturarum, or conspectus versuum suspectorum, note any prior deletion of 65.Google Scholar

18 Still, this use of ![]() remains difficult. For the omission of

remains difficult. For the omission of ![]() etc. with

etc. with ![]() , see LSJ A.II.2.a; Kühner-Gerth II.67c; Schwyzer-Debrunner 392,6;E., Bruhn, Anhang zu:Sophokles, Schneidewin, F. W.Nauck, A. (eds.), Achtes Bändchen (Berlin, 1899), 74: ‘§134.

, see LSJ A.II.2.a; Kühner-Gerth II.67c; Schwyzer-Debrunner 392,6;E., Bruhn, Anhang zu:Sophokles, Schneidewin, F. W.Nauck, A. (eds.), Achtes Bändchen (Berlin, 1899), 74: ‘§134.![]() mit zu ergänzendem

mit zu ergänzendem ![]() ’.Google Scholar

’.Google Scholar

19 Herwerden H. v., ‘Novae curae Euripideae’, Mnemosyne 31 (1903),261 –294, at 286: ‘Quia misere abundant verba ![]() , ambigo utrum deleto toto hoc versu in sequenti legam

, ambigo utrum deleto toto hoc versu in sequenti legam ![]() <δ′>

<δ′>![]() , an sic refingam:

, an sic refingam:![]() ’.

’.

20 Note how carefully not only ![]() and

and ![]() , but also

, but also ![]() and

and ![]() balance each other.

balance each other.

21 As opposed to glosses that intrude into the text, ‘either in place of what they were meant to explain or in addition to it’ (West, M. L., Textual Criticism and Editorial Technique [Stuttgart, 1973], 22f.)CrossRefGoogle Scholar. See Fraenkel III.564 on Aesch.Ag. 1226 (with literature); cf. 111.580,4 on 1256f. (‘expansion of an interjection to a trimeter’); Page (n. 16), 114 on Eur.I.A. 1416; West M. L., Studies in Aeschylus (Stuttgart, 1990),262; 173f. with Denniston-Page (ad I.) against the deletion of Aesch.Ag. 1 (cf. Fraenkel II.9 ad 1.) Cf.Tarrant, R. J., ‘Toward a Typology of Interpolation in Latin Poetry’, TAPhA 117 (1987), 281–298,Google Scholar at 290f. (‘gloss elaborated into a metrically appropriate insertion’; 1 owe this reference to Professor Nisbet); Housman A. E. (ed.), D. Iunii Iuvenalis Saturae (Cambridge, 2nd ed.,1931), xxxiii; xxxvf. This casts a shadow of doubt on many lines beginning with enjambement: Page (n. 16) 56f. (cf. also Eur.Or. 695. 716); Jachmann G., Binneninterpolation. II. Teil, NGG 1/9 (1936), 185–215, at 200–202 (cp. 194–8) = Textgeschichtliche Studien, Chr. Gnilka (ed.), (Beitrdge zur klassischen Philologie 143, Königstein/Ts., 1982), 550–80, at 565–7 (cf. 559–63), on proper names. The dating of this category remains uncertain; see Wilamowitz MoellendorffU. v. (ed.), Aeschyli Tragoediae (Berlin,1914), xxviii: ‘quae interpolations utrum iam in archetypo fuerint, an Byzantii demum confictae, diiudicare non audeo.’

22 Would ![]() not presuppose

not presuppose ![]() ?

?![]() and

and ![]() are both possible (and are confused at Archil, fr. 178 W.), but

are both possible (and are confused at Archil, fr. 178 W.), but ![]() seems preferable, because with or without iotacism its confusion with

seems preferable, because with or without iotacism its confusion with ![]() is slightly easier. Cf.Johnson, F., De coniunctivi et optativi usu Euripideo in enuntiatis finalibus et condicionalibus (Diss. Berlin, 1893; I owe this reference to Professor Diggle). The optative

is slightly easier. Cf.Johnson, F., De coniunctivi et optativi usu Euripideo in enuntiatis finalibus et condicionalibus (Diss. Berlin, 1893; I owe this reference to Professor Diggle). The optative ![]() was perhaps chosen to stress the force of the mood. Geelius (n. 9) 86 ad I. points out that the scholion on 64 presupposes the subjunctive:

was perhaps chosen to stress the force of the mood. Geelius (n. 9) 86 ad I. points out that the scholion on 64 presupposes the subjunctive:![]()

![]() (III.55, 18f. Dindorf).Google Scholar

(III.55, 18f. Dindorf).Google Scholar

23 This type of interpolation is well known: H.-Chr. Günther, ‘Textprobleme im Prolog der Aulischen Iphigenie des Euripides’, WüJbb N.F.13 (1987), 57–74, at 63, 34 (with literature on ‘Prädikatsergänzung’); Jachmann (n. 21) 189–92 = 554–7 (on interpolation following corruption); Tarrant (n. 21) 288f. (‘a mistaken impression of syntactical incompleteness has prompted an unnecessary attempt at restoration’);Nisbet, R. G. M., JRS 52 (1962), 235 =Google ScholarCollected Papers on Latin Literature (Oxford, 1995), 23 (cf. 240 =BICS 51 [1988], 95) on Juv. 6. 568. See also Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, U. v., Analecta Euripidea (Berlin, 1875), 205–209, on ![]() Google Scholar interpolations which make an implicit contrast explicit; cf. Page (n. 16) 5If. on Eur.Or. 51; Bond on Eur.Her. 452.

Google Scholar interpolations which make an implicit contrast explicit; cf. Page (n. 16) 5If. on Eur.Or. 51; Bond on Eur.Her. 452.