Article contents

Anaximenes and to ΚΡγΣΤΑΛΟΕΙΔΕΣ

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

The following remarks are frankly speculative, and their subject one on which certainty is unlikely to be attained. It seems worth offering them because, though the conclusions are only tentative, they were reached by way of some observations which have a certain interest of their own.

Anaximenes, we are told, said that the sun is flat like a leaf, and that it and the other heavenly bodies ‘ride upon’ the air owing to their flat shape, as does the earth also.

- Type

- Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1956

References

page 40 note 1 Aëtius (A 15), Hippolytus (A 7).

page 40 note 2 E.G.P. 78 n.

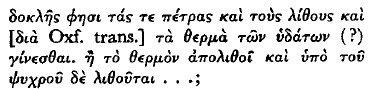

page 40 note 3 Heath takes ![]() to refer to their revolutions in their respective orbits, not to solstices, and suggests that this meaning could be got from the original text (Aët. 2. 14. 3) by reading

to refer to their revolutions in their respective orbits, not to solstices, and suggests that this meaning could be got from the original text (Aët. 2. 14. 3) by reading ![]() On this view A. will have anticipated Empedocles (A 54: ‘E.

On this view A. will have anticipated Empedocles (A 54: ‘E. ![]()

![]()

page 41 note 1 Who in all probability took it over from the Arabs: see Dreyer, , Planetary Systems (Cambridge, 190Google Scholar

page 41 note 2 Aët. 2. 7. 1 (Farm. A37), 2. n. 4 (A 38).

page 41 note 3 Cf. also [Ar.] Probl. 937 a 14: ![]()

![]()

page 41 note 4 Aët. 2. 11. 2 (Emped. A 51), Lactant. De opif. dei (ib.), Strom. A 30.

page 42 note 1 Baldry, H. C., ‘Embryological Analogies in Presocratic Cosmology’, C.Q. xxvi (1932), 27–34;CrossRefGoogle ScholarBurnet, , E.G.P. 348.Google Scholar Unfortunately Baldry's article has not had the attention it merits, and J. B. McDiarmid repeats Burnet's statement without comment in 1953 (‘Theophr. on the Presocratic Causes’, Han. Stud. Class. Philol. lxi. 93).Google Scholar

page 43 note 1 This last simile is so bizarre that one cannot help wondering whether the ![]() may not have been a turban, which ‘is wound’ round the head. This form of head gear may well have been as familiar in Miletus in A.'s time as it was in subsequent ages, until Ataturk frowned on it.

may not have been a turban, which ‘is wound’ round the head. This form of head gear may well have been as familiar in Miletus in A.'s time as it was in subsequent ages, until Ataturk frowned on it.

page 43 note 2 Dr. W. H. S. Jones, to whom I owe the parallel passage in Pliny, informs me that burned willow-bark (though not if completely reduced to ash) might contain traces of salicylic acid, the basis of modern corn-plasters.

page 43 note 3 Dr. Jones confirms my impression that ![]() = wart or callus does not occur in the Hippocratic corpus. If that is so, Theo-phrastus provides its first occurrence in extant literature.

= wart or callus does not occur in the Hippocratic corpus. If that is so, Theo-phrastus provides its first occurrence in extant literature.

page 44 note 1 It is not clear on what grounds Mr. G. B. Kerferd bases his statement in Mus. Helv. 1954, p. 121:Google Scholar ‘Even the word ![]() which Theophrastus may have used of Anaximenes in relation to Anaximander (VS 6 13 A 5 = Dox. 476) probably refers to affinities in doctrine’ (as opposed to a per sonal relationship). In the absence of support it seems unlikely.

which Theophrastus may have used of Anaximenes in relation to Anaximander (VS 6 13 A 5 = Dox. 476) probably refers to affinities in doctrine’ (as opposed to a per sonal relationship). In the absence of support it seems unlikely.

page 44 note 2 This could be enlarged upon indefinitely from ancient sources, and has already begun to attract the attention of classical scholar ship. Here it will be sufficient to mention Oceanus and Tethys as parents of the gods in Homer (Il. 14. 20; also Oceanus as the genesis of all things in line 246), comparing this with the male and female principles of water, Apsu and Ti'amat, who are the origin of all things in the Babylonian Enuma Elish, and with the birth of the world, and in particular of living things, from the primal water Nün in Egyptian cosmogony. (For easily accessible accounts of these Meso-potamian and Egyptian beliefs see the chapters by Wilson, John A. and Jacobsen, T. in Before Philosophy, Pelican, 1949.)Google Scholar Aristotle has been quite unjustly blamed for mentioning the Homer passage in connexion with Thales (Metaph. A, 983 b 30). There is of course no question of his putting the two on the same level, as Mr. McDiarmid suggests (op. cit. 92): otherwise Thales would not be for him ![]()

page 44 note 3 Cf. Guthrie, , Greeks and their Gods, 1950 (1954). 137 ff.Google Scholar

page 44 note 4 Aët. 1. 3. 4 ![]()

![]()

![]() . The suspicion that

. The suspicion that ![]() is a Stoic intrusion grows less when one observes that Aristotle ascribes to the Pytha goreans a view of the universe as breathing in from an

is a Stoic intrusion grows less when one observes that Aristotle ascribes to the Pytha goreans a view of the universe as breathing in from an ![]() (Phys. 213 b 23).

(Phys. 213 b 23).

- 3

- Cited by