Article contents

Alcman and Pythagoras1

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

By the colours and decoration of a vase fragment one determines the period and style to which the original belonged; while its physical contours show from what part of the original it comes. The material may be insufficient for a reconstruction of the whole design. But it is often legitimate to go beyond what is actually contained in the preserved pieces.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1967

References

1 The term ‘Presocratic’ has so established itself that we should greatly inconvenience ourselves by abandoning it now. But it has two grave disadvantages: it exaggerates the effect of Socrates; and it lumps together an assortment of people—priests, doctors, vagabond poets, experimental physicists—whose methods and intentions were very various, and implies that they were somehow united in a common search.

3 C.Q. N.s. xiii (1963), 154–6.Google Scholar

1 See Kirk-Raven, , The Presocratic Philosophers, pp. 19–24.Google Scholar

2 Th. 124, 371.

3 Ibid. 371, cf. 19.

4 Anaxagoras Bi, Ar. Av. 6937ndash;5, ‘Linus’ ap. D.L. 1. 4, A.R. 1. 496–8, Ov. M. 1. 5–20, Heitsch, Griech. Dichterfragmente d. röm. Kaiserzeit, nos. 24 verso 1–4 and 46. 6–10.

5 Transl. Speiser, E. A. in A.N.E.T.2, pp. 60 f.Google Scholar See also the Vedic hymn in Zaehner, R. C., Hindu Scriptures (1966), 11 f.Google Scholar

1 Bowra, C. M., Greek Lyric Poetry, 2nd ed. (1961), p. 26.Google Scholar

2 Schwabl, H., R.-E. Suppl. ix. 1510, with literature.Google Scholar

3 The sea is ![]() , Il. 15. 381, etc.; cf. Od. 12. 259

, Il. 15. 381, etc.; cf. Od. 12. 259 ![]() . Impassable water is

. Impassable water is ![]() , Pl. Tim. 25 d.

, Pl. Tim. 25 d. ![]() is not used of roads on land. The word is discussed by Rudolph, M., πOPO∑, Diss. Marburg, 1912;Google ScholarBecker, O., Das Bild des Weges (= Hermes Einzelschr iv [1937]), 23–34.Google Scholar It may be worth recalling that

is not used of roads on land. The word is discussed by Rudolph, M., πOPO∑, Diss. Marburg, 1912;Google ScholarBecker, O., Das Bild des Weges (= Hermes Einzelschr iv [1937]), 23–34.Google Scholar It may be worth recalling that ![]() originally meant ‘path’ (Boisacq s.v.; Moorhouse, A. C., C.Q. xxxiv (1940), 123–8, xxxv (1941), 90–96).CrossRefGoogle Scholar For the impassability of the primeval ocean cf. Ovid's innabilis undo (M. 1. 16).

originally meant ‘path’ (Boisacq s.v.; Moorhouse, A. C., C.Q. xxxiv (1940), 123–8, xxxv (1941), 90–96).CrossRefGoogle Scholar For the impassability of the primeval ocean cf. Ovid's innabilis undo (M. 1. 16).

A navigator needs a ![]() such as a guiding star, E. Hec. 1273. Cf. from late epic A.R. 4. 1538

such as a guiding star, E. Hec. 1273. Cf. from late epic A.R. 4. 1538 ![]() Opp. H. I. 364

Opp. H. I. 364 ![]()

![]() [Orph.] A. 1150 (1155)

[Orph.] A. 1150 (1155) ![]()

![]() , Nonn. D. 13. 537

, Nonn. D. 13. 537 ![]()

![]()

4 H. Lloyd-Jones, ap. Bowra, p. 26 n. 1;Google Scholar Schwabl, 1467; C.Q. N.S. xiii (1963), 154–5;Google ScholarFränkel, H., Dichtung und Philosophie, 2nd ed. (1962), p. 290 n. 2,Google Scholar which I ought to have seen and referred to. One of us might have recalled in this connexion Alcman's play on names in fr. 3. 73–74 ![]()

![]() (cf. also C.Q. N.S. xv [1965], 188).Google Scholar

(cf. also C.Q. N.S. xv [1965], 188).Google Scholar

5 Cf. Schwabl, 1467: ‘Thetis … ist hier “die die Dinge zu setzen weiβ”, zugleich aber erhebt sich die Frage, ob ihr noch etwas vom Wasserwesen geblieben ist.’ Burkert, W., Gnomon xxxv (1963), 828:Google Scholar ‘Thetis als die berühmteste der Nereiden konnte dann vielleicht die Urflut repräsentieren.’

1 ‘Wenn dann die ![]() aber mit

aber mit ![]() (Z. 18) verglichen wird, weist dies in der Konfrontierung mit Thetis auf eine zweite, griechische Traditionslinie…: glühendes Metall und Wasserbad als Urbild alles “Entstehens” in Handwerk und Brauchtum der Schmiede. Thetis war es, die den stürzenden Hephaistos auffing (∑ 395 ff.)—der Mythos spiegelt wohl eine Schmiede–Initiation’, and so on. (Ibid.)

(Z. 18) verglichen wird, weist dies in der Konfrontierung mit Thetis auf eine zweite, griechische Traditionslinie…: glühendes Metall und Wasserbad als Urbild alles “Entstehens” in Handwerk und Brauchtum der Schmiede. Thetis war es, die den stürzenden Hephaistos auffing (∑ 395 ff.)—der Mythos spiegelt wohl eine Schmiede–Initiation’, and so on. (Ibid.)

2 e.g. Arist. Pol. 1256a![]()

![]()

![]()

3 The locus classicus for the Aristotelian causes is Physics 194b16 ff.; but more helpful here is the application of them to the pre-Aristotelian cosmogonies in Metaphysics A, beginning at 983a24 ff. It is interesting that although Aristotle mentions early poetic cosmogonies (not only Hesiod, but even the passing allusions in Homer), he does not mention Alcman. Perhaps he did not know him.

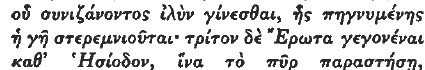

1 Zeno interpreted Chaos as water: Sch. A.R. I. 496–8b ![]() (fr. 104, SVF i. 29)

(fr. 104, SVF i. 29) ![]()

![]() Cf. Prob. in Virg. E. 6. 31, p. 21. 14 Keil (Zeno fr. 103). In the Stoic cosmology as summarized by D.L. 7. 137, fire is the outermost sphere, aer is next, then water, and the

Cf. Prob. in Virg. E. 6. 31, p. 21. 14 Keil (Zeno fr. 103). In the Stoic cosmology as summarized by D.L. 7. 137, fire is the outermost sphere, aer is next, then water, and the ![]()

![]() is earth. In the Hesiod scholia there is some confusion: Zeno is reported as emphasizing that earth is the

is earth. In the Hesiod scholia there is some confusion: Zeno is reported as emphasizing that earth is the ![]() even of

even of ![]() , but v.l. CK

, but v.l. CK ![]() ), and as athetizing a verse or verses in consequence

), and as athetizing a verse or verses in consequence ![]()

![]()

![]() (fr. 105). If the note referred in the first instance to

(fr. 105). If the note referred in the first instance to ![]() , ‘the following verse’ would be 117; and the athetesis of 117 (with 118, if Zeno read it) would in fact bring Hesiod into line with the Stoic system, so long as the

, ‘the following verse’ would be 117; and the athetesis of 117 (with 118, if Zeno read it) would in fact bring Hesiod into line with the Stoic system, so long as the ![]() is assumed as preexisting: 1. Chaos = water; 2. Tartarus = aer; 3. Eros = fire. The scholia give water as one of three interpretations of Chaos; they explain Tartarus as being aer; and they attribute to

is assumed as preexisting: 1. Chaos = water; 2. Tartarus = aer; 3. Eros = fire. The scholia give water as one of three interpretations of Chaos; they explain Tartarus as being aer; and they attribute to ![]() the interpretation of Eros as fire.

the interpretation of Eros as fire.

1 He seems an Egyptian overlay. See Morenz, S. in Aus Antike u. Orient (Festschr. Schubart), pp. 71 ff.Google Scholar

2 Loc. cit.

3 Contrast this: ‘We can quickly dispose of the question whether any non-Greek elements are to be found in him [Alcman] … there is no question of his being influenced by any foreign literature; there was no contemporary foreign literature, at any rate nothing known to any Greek; and there was no contact with any civilization of the past except indirectly through Homer and Hesiod… His subject-matter, when it is not himself and his chorus girls, is usually some local tale of no interest to anyone but a Spartan—even his gods and goddesses are parochial mumbo-jumbo, hardly recognizable to a Greek from another city.’ (Page, D. L., The Listener lxi (01–07 1959), 110.)Google Scholar

1 It will be recognized that I am simplifying a complex and controversial matter. On the fundamental position of the ![]() antithesis in the whole, see Guthrie, W. K. C., History of Greek Philosophy, i. 245 ff.;Google ScholarBurkert, W., Weisheit und Wissenschaft, p. 30.Google Scholar

antithesis in the whole, see Guthrie, W. K. C., History of Greek Philosophy, i. 245 ff.;Google ScholarBurkert, W., Weisheit und Wissenschaft, p. 30.Google Scholar

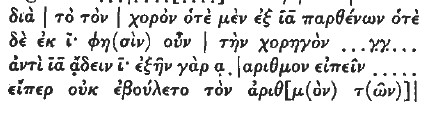

2 I cannot refrain from citing, though it adds nothing of significance to the argument, Arist. Rhet. 1357b9 ![]()

![]()

3 In the version of the lost Cambridge manuscript, represented by the Basel edition:

4 I abide by the accepted supplement of ![]() : alternatives could be devised (

: alternatives could be devised (![]() , etc.), but I cannot think of one that is plausible.

, etc.), but I cannot think of one that is plausible.

5 ap. Bowra, , op. cit., 42.Google Scholar

1 The metaphor may have been suggested to Pindar by ![]() .

.

1 Page, , Alcman, The Partheneion, pp. 34 f.;Google ScholarFrankel, , op. cit., 1st ed., p. 223Google Scholar n. 1 (= 2nd ed., p. 183 n. 10). The interpretation was not new: it was known to Höfer (Roscher, iii. 2776), who ascribes it to Diels, Hermes xxxi (1896), 345—where, however, it is not to be found.Google Scholar

3 It must, I think, be qualified by a genitive or equivalent: I can attach no meaning to ![]() as an independent proposition.

as an independent proposition.

4 e.g. Medea in A.R. 4. 43, Aphrodite in Bion Adonis 21, various distracted females in Nonnus; the sensual touch appealed to late poets.

5 Hes, . Op. 344 f.Google Scholar![]()

![]()

![]() A. PV Ioc. cit., Theoc. 24. 36. In the PV passage,

A. PV Ioc. cit., Theoc. 24. 36. In the PV passage, ![]() emphasizes the miraculous swiftness of the Oceanids’ cars rather than the altitude they attain.

emphasizes the miraculous swiftness of the Oceanids’ cars rather than the altitude they attain.

6 Poros accordingly represents something a little different here from what he represented in the cosmogony. We should not expect him necessarily to mean the same; after all, Aisa has no place in the cosmogony, so we are not going to be able to reconcile the two passages. On the scholium about Poros, cf. above, p. 4.

1 Actually to supplement lines 13–15 is difficult. In 15, ![]() might do (for a statement about

might do (for a statement about ![]() cf. Il. 15. 490

cf. Il. 15. 490 ![]()

![]() less attractive, and it would involve giving Aisa another male companion to account for

less attractive, and it would involve giving Aisa another male companion to account for ![]() . It looks as if

. It looks as if ![]() must go in 14 (Blass). ‘Of the gods’ is then needed with

must go in 14 (Blass). ‘Of the gods’ is then needed with ![]()

![]() , but cannot be restored in 13, so far as I see, without some unlikely combination of particles such as

, but cannot be restored in 13, so far as I see, without some unlikely combination of particles such as ![]() (Denniston 536) or

(Denniston 536) or ![]() . Possibly it was understood from the preceding sentence.

. Possibly it was understood from the preceding sentence.

2 Op. cit. 184. He quotes among other relevant passages fr. 45 ![]()

![]()

3 Fr. 41 ![]()

![]() .

.

4 Hermes xxxi (1896), 347.Google Scholar

1 Like other post-Hellenistic authors, Horace does not distinguish between Titans, Giants, Aloadae, Typhoeus, and Hundred-Handers, and he mentions them all in the passage that follows. But it is fair to sum them up as the Giants, since he is not thinking of a war of Olympians against older gods but of an assault upon Olympus from below (51–52); and they are repulsed by Pallas, Vulcan, Juno, and Apollo, three of whom were unborn at the time of Hesiod's Titanomachy.

2 See Fraenkel, E., Horace, pp. 273–85.Google Scholar

1 C.Q. N.s. xv (1965), 194 ff.Google Scholar

1 Mus. Helv. xv (1958), 83.Google Scholar

3 Alcman cannot be saying that anyone concerned in this song is more tuneful than the Sirens, especially as he goes on to say ‘for they are goddesses’.

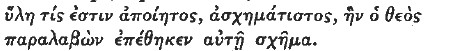

1 I can only think of the Elevens at Athens and Delos. The scholiast is evidently guessing: ![]()

![]() This perhaps means: ‘Eleven: he does not mean the Sirens

This perhaps means: ‘Eleven: he does not mean the Sirens ![]() , it is because the choir (consists) part of the time of eleven girls, part of the time of ten: he is (subtracting) the choir-leader and saying that ten are singing instead of eleven. For he could have said …without a number’

, it is because the choir (consists) part of the time of eleven girls, part of the time of ten: he is (subtracting) the choir-leader and saying that ten are singing instead of eleven. For he could have said …without a number’ ![]() , with false syllabic division due to misreading as

, with false syllabic division due to misreading as ![]() So R. Merkelbach in a seminar), ‘if he did not want (to state) the number of the girls’.

So R. Merkelbach in a seminar), ‘if he did not want (to state) the number of the girls’.

1 Plato is no doubt thinking of a diatonic scale, as in the Timaeus. Cf. M. I. Henderson, , C.Q. xxxvi (1942), 95.Google Scholar

2 The idea of the music of the spheres is certainly older than Plato in some form or other; see Guthrie, , op. cit., pp. 295–301;Google ScholarBurkert, , op. cit., pp. 328–35.Google Scholar

3 Iambl. VP 82. On the antiquity of the ![]() . see Burkert, , op. cit., pp. 150 ff.,Google Scholar 172; on this one, ibid., p. 377.

. see Burkert, , op. cit., pp. 150 ff.,Google Scholar 172; on this one, ibid., p. 377.

4 Other notes would presumably be thought of as perversions of the divine ones.

5 Arist. fr. 196 (ap. Porph. VP 41), al.

6 E. Hel. 1346 ![]() .

.

7 Apollod. 224 F no; Theoc. 2. 36 with Gow's note.

8 It is perhaps reflected in poetic metaphors like Od. 21. 410 f. ![]()

9 Note h. Herm. 38 (Hermes to the tortoise) ![]()

1 Harrison, J. E., Prolegomena, pp. 197 ff.;Google ScholarBuschor, E., Die Musen des Jenseits (1944).Google Scholar Hades, like the Sirens, became transferred to heaven.—Primitive peoples often regard musical instruments as having something supernatural about them. They use them for summoning spirits, which perhaps implies that the musical sounds are what the spirits recognize as speech. In Polynesia the god Tane is hailed by means of the drum, and at the same time the sound of the drum is the voice of Tane. Among the bushmen of Surinam, the drum is so far regarded as animate that it is offered occasional drinks; but it has connexions with the world of the dead, and is thought to conduct men there. (I take this information from J. A. MacCulloch in Hastings's, Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, ix. 6;Google Scholar cf. also Dodds, E. R., The Greeks and the Irrational, p. 175, n. 119.) In the Old Testament we find references to musical instruments used as instruments of prophecy: 1 Sam. x. 5, 1 Chron. xxv. 1–3, 2 Kings hi. 15.Google Scholar

2 Hdt. 6. 38, etc. The Spartan kings were heroized at death (Xen, . Resp. Lac. 15. 9), so the sounding of bronze may have been connected with the preservation of their souls from the clutches of Hades.Google Scholar

3 Cf. C.Q. N.S. xv (1965), 200.Google Scholar

4 Cf. 2 Chron. v. 12–13 ‘Also the Levites which were the singers, all of them of Asaph, of Heman, of Jeduthun, with their sons and their brethren, being arrayed in white linen, having cymbals and psalteries and harps, stood at the east end of the altar, and with them an hundred and twenty priests sound– ing with trumpets: It came even to pass, as the trumpeters and singers were as one, to make one sound to be heard in praising and thanking the Lord; and when they lifted up their voice with the trumpets and cymbals and instruments of musick, and praised the Lord, saying, For he is good; for his mercy endureth for ever: that then the house was filled with a cloud, even the house of the Lord.’

5 In what follows I am greatly indebted to the late Mrs. M. I. Henderson for helping me to understand a little of a compli– cated and difficult subject.

1 Hence seven- and eight-stringed lyres, both represented on Attic Black–figure, though vases are unreliable evidence for numbers of strings.

2 Eight Sirens: Plato. Eight Muses: Crates ap. Arnob. 3. 37; Serv, . Aen. i. 8;Google ScholarAuson, . Opusc. p. 247.Google Scholar 64 Peiper. Seven Muses: Epich. fr. 41 Kaibel; Myrsilus 477 F 7. Three, named ![]() : Plut. Qu. Conv, . 744 d.Google Scholar

: Plut. Qu. Conv, . 744 d.Google Scholar

3 One would like to know how many strings he had on his ![]() (fr. 101).

(fr. 101).

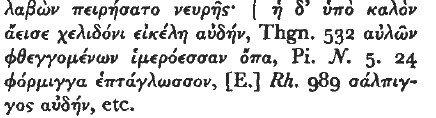

4 28. 51, ii. 158 ![]()

.

.

1 See Burkert's index s.vv. ‘Babylonische Astronomic’ and ‘Babylonische Mathematik’.

2 C.Q. N.S. xiii (1963), 161–3.Google Scholar

3 Tigerstedt, E. N., Eranos li (1953), 8–13.Google Scholar

4 C.Q. N.s. xiii (1963), 169.Google Scholar

5 Ibid. 171.

6 According to another Pythagorean ![]() , the Pleiades were ‘the lyre of the Muses’. If a Spartan girls' choir called itself the Pleiades, it is conceivable that this was connected with some such fancy.

, the Pleiades were ‘the lyre of the Muses’. If a Spartan girls' choir called itself the Pleiades, it is conceivable that this was connected with some such fancy.

- 15

- Cited by