I. Introduction

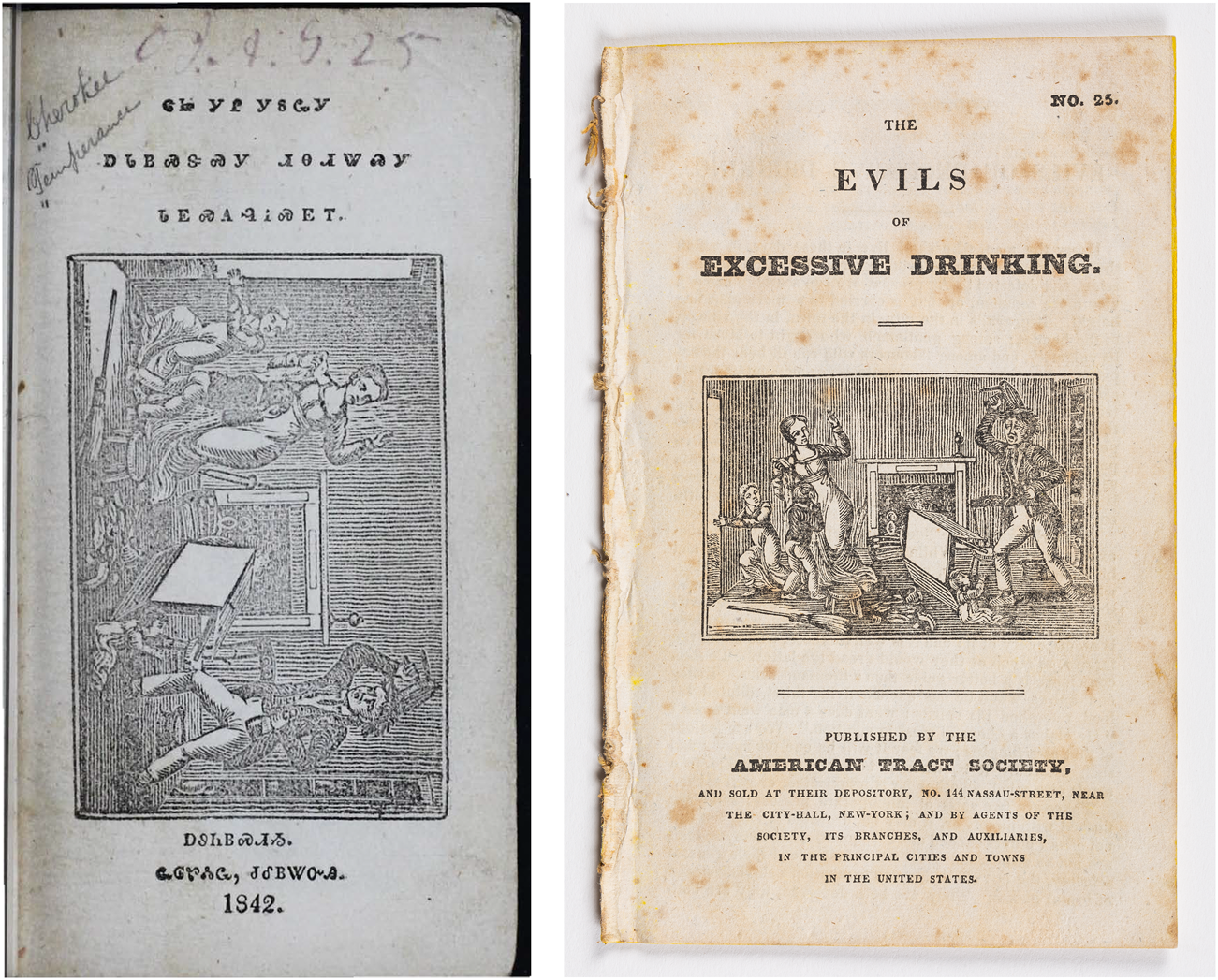

Power can feel combative and aggressive, like a shove. Sometimes, power works more subtly, planting new ideas and practices in a person without the conscious mind always knowing it. The argument of this article is that nineteenth-century Cherokee printers exerted the latter sort of power in their design of the material formats of Christian print media, which they intended to alter the experience of media's beholders. It looks specifically to the tract Poor Sarah as an illuminating example because its two editions, from 1833 and 1843, afford a comparative analysis of its material elements from before and after the tribe's forced removal from Cherokee Nation to Indian Territory (Figure 1). The contrast between the editions is striking. Even at a glance, it is apparent that the first tract is large in scale, with elaborate typography, while the second is small and stripped down. The later version features the same image as before, now rotated ninety degrees—on its face an odd choice, one that calls for explanation. The two tracts offer sites for considering how Cherokees articulated political arguments through media design, a deliberately quiet form of power that engendered certain experiences in their viewers and readers. Cherokees designed media, and intended media to have effects, in ways that addressed their changing circumstances wrought by the violence of US empire and settler colonial incursion.

Fig. 1. At left, Poor Sarah; or the Indian Woman, trans. E. Boudinot (New Echota, [Cherokee Nation]: J. F. Wheeler and J. Candy, Printers, 1833), 12 pages, 9.9 x 17 cm. At right, Poor Sarah (Park Hill, [Cherokee Nation]: John Candy, Printer, 1843), 16 pages, 7.8 x 12.6 cm. Courtesy, Newberry Library, Chicago, the Ayer North and Middle American Indian Linguistics Collection and the Graff Collection of Western Americana.

The argument has two parts corresponding to the two editions. First, it demonstrates how the printers of the first pre-removal Poor Sarah (1833), under the leadership of the Cherokee statesman and translator Elias Boudinot (Galagina [Buck] Watie), designed their tract to evoke the look of typical Anglo-Protestant evangelical tracts produced by the American Tract Society (ATS). They expected both their white and Cherokee audiences to grasp those similarities, consciously or unconsciously. Boudinot and the other printers’ decisions about material format contributed to the well-known strategy among elite Cherokees, ascendant in the years leading up to removal, to imitate the conventions of white culture. They intended their Poor Sarah to win recognition from white allies, who, they hoped, would be more liable to respect treaty rights, acknowledge tribal sovereignty, and assist in fighting removal. In other words, the printers used the material format of the tract in ways consonant with a broader Cherokee strategy at the time for perseverance and self-determination. That this strategy was material is an indication of how Cherokee political action could be subtle by design. The printers finessed a distinctive capacity of materiality, namely, to encourage certain attitudes, feelings, and responses but without brashly calling attention to its doing so. Unlike confrontational forms of engagement such as discursive argument, material manipulations were more tacit. They were liable to merge with the background so as to appear as simply given and uncontroversial. Such efforts to cultivate support via materiality ought to be considered as deliberate and tactical choices.

The article goes on to argue that the revision in the format of the second edition of Poor Sarah (1843), manufactured ten years later, contributed to a shift in Cherokee political and cultural techniques in the post-removal period. The goal was no longer to be legible to white beholders by emulating white material forms. At the town of Park Hill in the recently established Cherokee Nation in the west, in Indian Territory, printers under the new leadership of John Candy (Walosudlawa [Wart-covered frog]) transformed the material format of Poor Sarah on their reconstituted press: they made it smaller, reoriented the image, rearranged the layout, and selected new typefaces. All these design choices explicitly moved away from the ATS house style, which is also to say, from the style of Anglo-Protestant print culture more generally. Enthusiasm for the shopworn strategy of religious acculturation dampened in the years immediately following removal, because it had become clear that emulating Anglo-Protestant conventions had failed. The land had been lost. What was needed now was a material format that would serve Cherokee Christians in the west and better address their changing circumstances. Thus they made the new Poor Sarah to be a Cherokee object aimed at a Cherokee readership that was in the midst of an Indigenization of Christian practices. What did not change between 1833 and 1843, however, was the printers’ awareness of the power afforded by material formats. The materiality of print culture offered an arena for political and social action that was valuable for its ability to wage effects on viewers and readers in quietly compelling ways.

II. Materiality and Format

My interest in the materiality of these two editions of Poor Sarah takes theoretical and methodological cues from the broader material turn across the humanities, and especially from the overlapping fields of book history, bibliography, and material texts. Specialists in these areas regard texts as objects whose physical characteristics furnish primary forms of evidence. A material-textual analysis of a printed text like a pamphlet or a book, for instance, could examine qualities such as its typography, layout, binding, dimensions, images, paper, and marginalia.Footnote 1 These sorts of object-based approaches have proven especially fruitful in Indigenous studies. Through the examination of materials including wampum, quillworked bindings, birchbark scrolls, scrapbooks, handcrafted maps, and carved gravestones, in addition to printed texts that are my focus here, scholars have demonstrated the value of material-textual methods for recovering and analyzing Indigenous labor, ideas, and creativity.Footnote 2 This article's parsing of the materiality of the two editions of Poor Sarah draws on these scholarly movements around materiality in its alertness to the ways in which Cherokees constructed textual materialities to have effects and make arguments, in ways beyond a text's semantic content alone. This article thus combines a more traditional content analysis of textual sources, including Cherokee and missionary records, with a material analysis of the Cherokees’ publications as objects.

The term I use to describe the materiality of Cherokee tracts is format. While several other terms such as medium, form, or just materiality might have sufficed, my choice of term is indebted to the theoretical work of the book and media historian Meredith McGill. In her essay on the concept, McGill explains how “format” comes from the book trades, used by printers and publishers to refer to their decisions regarding the materiality of their publications, and in ways intended to anticipate and shape reception. In the nineteenth-century printshop as much as in today's modern publishing house, formatting decisions were not arbitrary. Publishers knew that formats guided reception and designed them accordingly. For instance, if ease in hand-to-hand circulation was desired, a slim pamphlet was the go-to format. The format of a gilded leatherbound tome, by contrast, was suited for display in a bourgeois parlor. The fact that publishers engineered formats, in McGill's words, “reminds us that ‘reception’ is not separable from and subsequent to book production. Rather, publishers theorize the potential field of a text's reception with care and urgency as they commit labor and material resources to the printing of a book.”Footnote 3 In other words, format names a form of power embedded in media objects that directs the practices of media's readers and users. I would add, too, that this material power is not coercive. Formats do not demand or compel, as in a material determinism. What formats can do is coax, suggest, and encourage patterns of reception, in subtler ways more in line with how actor-network theory and new materialisms describe the power of material things.Footnote 4 My argument is that Cherokee printers understood and deployed this sort of unobtrusive, soundless power.

The printer who theorized the power of materiality most explicitly was Elias Boudinot (Galagina [Buck] Watie), who at twenty-nine years old led the team of printers that carried out the publication of Poor Sarah's first edition in 1833. The details of his life are well known to scholars of Cherokee history.Footnote 5 During Galagina's studies at a mission school run by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), his teachers renamed him after the New Jersey Presbyterian Elias Boudinot, the former president of the American Bible Society and one of the mission school's benefactors. A star student, Boudinot the Cherokee (who pronounced his surname with a hard “t” and spelled it “Boudinott” until 1832) later traveled to attend the ABCFM's so-called heathen school in Connecticut, where he formally affiliated with Congregationalism in 1820 before returning to Cherokee Nation in 1822. When, in 1826, the members of the Cherokee National Council resolved to acquire a printing press and a set of types for Cherokee Nation, they nominated Boudinot to tour northeastern Protestant churches and assist in raising funds. After his tour's completion, Boudinot edited his speech for publication as a pamphlet called Address to the Whites (1826) that was distributed in elite northeastern evangelical circles.Footnote 6

The Address offers a striking window onto Boudinot's theories regarding the power of material display, especially the display of Christian acculturation as a route toward the perseverance of rights, lands, and culture. While the idea of acculturation as a political strategy was a view he shared with many Cherokee leaders, Boudinot was exceptional in articulating how the material ways in which Cherokees showed their Christian civilization made a veridical statement of the truth of that performance. Material display had the power to oblige white observers to lend their support in ways that discursive techniques never could on their own:

The time has arrived when speculations and conjectures as to the practicability of civilizing the Indians must forever cease. It needs not abstract reasoning to prove this position. It needs not the display of language to prove to the minds of good men, that Indians are susceptible of attainments necessary to the formation of polished society. It needs not the power of argument on the nature of man, to silence forever the remark that “it is the purpose of the Almighty that the Indians should be exterminated.” It needs only that the world should know what we have done in the last few years, to foresee what yet we may do with the assistance of our white brethren, and that of the common Parent of us all.Footnote 7

What I find most noteworthy is Boudinot's assurance that the most powerful way to win white supporters was through making Cherokee civilization visible. He had little regard for flimsier tools like “abstract reasoning,” “the display of language,” or “the power of argument.” My point is that Boudinot's remarks speak to his attunement to the efficacy of material exhibition, even beyond that of other Cherokee statesmen who shared his same general acculturation strategies. Boudinot wanted Cherokees not merely to tell, but to show, and in the case of his edition of Poor Sarah, to apply his long-gestating theories to show specifically through material format that our sacred books are in fact your sacred books, not only in their content but more viscerally in their material forms. This article's parsing of the material formats of the publications, then, follows the lead of Boudinot and draws on the insights of other theorists of materiality like McGill in analyzing a key way in which Cherokees crafted Christian tracts to engage in political action during the removal crisis and in its aftermath.

III. Poor Sarah's Contexts: The Source Text, Removal, Christianity, and the Syllabary

Before exploring the material formats of Poor Sarah, some context will be useful, beginning with information about the history and contents of the earlier English-language version that provided the source text for the Cherokee translation. Its author was the white woman Phoebe Hinsdale Brown, who published it over two installments in 1820 in the New Haven Congregationalist periodical The Religious Intelligencer. Footnote 8 Brown narrates her first-person encounters with Sarah, an elderly and impoverished Indigenous woman and convert to Christianity living in western Connecticut. Though Brown does not offer identifying details, contemporaneous sources recognize the woman as a Mohegan named Sarah Rogers.Footnote 9 The story presents a variation on a common genre of Anglo-Protestant biography of the period, which describes a protagonist with a wrenching conversion experience, who, in the end, declines and dies a “good death.”Footnote 10 Brown's story was also typical of this genre's treatment of nonwhite people and the poor of all races, in that Brown valorizes Sarah for suffering virtuously, while condescending to her as childlike.Footnote 11 Figures like Sarah were intended to serve as exemplars, both for fellow marginalized readers who Christian publishers regarded as in need of religious correction, and for middle-class readers, like the subscribers to the New Haven Religious Intelligencer, who could be edified by their fortitude but from a safe distance.Footnote 12

Brown's story proved popular. Through the 1820s on both sides of the Atlantic, it was reprinted many times over in periodicals and as a standalone tract. (In this article, I will use the word tract to describe a pamphlet with religious content, with the larger category pamphlet referring to any slim codex that lacks a hard binding.) When, in 1825, the goliath evangelical publisher the American Tract Society (ATS) established itself in New York, it featured Poor Sarah in its principal tract series. The ATS gave the title a wide circulation in the United States by selling parcels of tracts at below-market rates to its benevolent auxiliary distributors across the country, who in turn gave them away to readers as charity.Footnote 13

Cherokees printed their own Cherokee-language edition of Poor Sarah in 1833, in the middle of a notorious period in their history while under extreme duress from white settler colonialism. The story of the Cherokees’ struggles and perseverance during that time is familiar to students of Indigenous history, and I offer only the broadest outlines here. Following the American Revolution, the newly formed United States forced Cherokees to broker treaties that reduced their ancestral lands by some twenty million acres, eventually confining them to a hilly tract across parts of what are today the states of Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama. Partly to better negotiate with US empire during this period, Cherokees shifted from a governance structure based on town councils to a more centralized administration under the aegis of the Cherokee Nation. The Nation borrowed from and reworked elements of US polity, for instance establishing the office of principal chief in 1794, a supreme court in 1822, and a written constitution and bicameral legislature called the National Council in 1827. US aggression only intensified, however. In 1830, Andrew Jackson signed the infamous Indian Removal Act into law. Twice Cherokee Nation fought removal in the US Supreme Court, in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832), though the latter's ruling in the Cherokees’ favor was ignored by both the state of Georgia and Jackson. All the while Cherokees endured increasing harassment and violence by Georgia's government and state militia. Seeing no remaining options, in 1835, Cherokee leaders comprising a group known as the Treaty Party signed a removal treaty called the Treaty of New Echota. That group included Poor Sarah's printer and translator Elias Boudinot.Footnote 14

Historians of religion have examined how, amid these existential threats and in a subordinate position with respect to US imperial power, some Cherokees affiliated with Protestant Christianity.Footnote 15 Most who did so were elites.Footnote 16 Overall, they represented a minority of the Nation's citizens, with church membership hovering around ten percent in the 1830s.Footnote 17 That ten percent was spread among the competing denominations operating missions in Cherokee Nation, including the Moravians who arrived in 1801, followed by Congregationalists and Presbyterians cooperating as the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (the ABCFM or “the Board”) in 1817, the Baptists in 1818, and the Methodists in 1822. As many scholars have emphasized, Cherokees’ church membership must be understood in the context of their wager that acculturation, including religious acculturation, would win powerful white allies and respect from the US government, and thus increase the likelihood of remaining on their land.Footnote 18 Following Daniel Heath Justice, here acculturation means “the adaptation of certain Eurowestern ways into a larger Cherokee context.”Footnote 19

The Cherokees’ strategy of religious acculturation emerged out of specific histories of colonialism and missionization in North America. It was partly a response to a pervasive colonialist logic, with roots in the Doctrine of Discovery stretching back to the fifteenth century, which held that Indigenous peoples’ perceived lack of religion justified stealing their land.Footnote 20 As Sylvester A. Johnson has further demonstrated, it was also a response to a lobbying effort by the ABCFM, which was the most powerful foreign mission organization in the United States. Beginning in the 1810s, Board missionaries framed acculturation as a matter of life or death to leaders of the Cherokee and other Indigenous nations, warning them in explicit terms that the US military would remove and eliminate those tribes that failed to appear Christian and civilized.Footnote 21 The missionaries thus presented Cherokees with a formidable incentive to acculturate to the settlers’ religion. Fears of the consequences of not complying intensified after Jackson's election and as the nightmare of removal increasingly appeared as a real possibility.

A strategic articulation of acculturation may be heard in Principal Chief John Ross's 1836 memorial letter to the US Congress protesting removal and the removal treaty. As the letter crescendos to its closing sentences, Ross reminds his readers of his people's rapid embrace of the settlers’ culture, including their religion:

The wildness of the forest has given place to comfortable dwellings and cultivated fields, stocked with the various domestic animals. Mental culture, industrious habits, and domestic enjoyments, have succeeded the rudeness of the savage state.

We have learned your religion also. We have read your Sacred books. Hundreds of our people have embraced their doctrines, practised the virtues they teach, cherished the hopes they awaken, and rejoiced in the consolations which they afford. . . To you, therefore, we look! . . .To you we address our reiterated prayers. Spare our people!Footnote 22

Ross's rhetorical maneuver from an avowal that “we have learned your religion” to a petition to “spare our people!” positioned the latter as the clear consequence of the former. These words may be taken as representative of a more general attitude and practice among many Christian Cherokees in this period including Boudinot, for whom affiliation with Christianity was inseparable from their desire to win US recognition of their rights and to remain on their land.

Another aspect of Cherokee life undergoing changes in the years prior to Poor Sarah's publication was the invention and widespread use of the Cherokee syllabary, a phenomenon that scholars have likewise investigated in detail.Footnote 23 The syllabary was a character-based form of writing created by the famous Sequoyah (George Guess). Observing of white people's books that he saw “nothing in it so very wonderful and difficult,” Sequoyah spent several years perfecting the eighty-six glyphs that comprised the system.Footnote 24 When he presented his syllabary to the National Council in 1821, council members formally accepted it, and soon after Cherokees widely adopted the new medium. A flourishing manuscript culture followed.Footnote 25 The brilliance of the syllabary lay in the fact that because each of its glyphs represented a syllable in the spoken language, Cherokee speakers could learn it relatively rapidly. Federal census records bear this out. According to data from 1835, out of approximately fifteen thousand Cherokee Nation citizens, 3,914 were readers of the syllabary (compared to 1,070 readers of English).Footnote 26 As Ellen Cushman has demonstrated, the embrace of the syllabary was strategic in terms of tribal perseverance. At once an external performance and internal tool, the syllabary functioned, in the words of Cushman and Naomi Trevino, “both as an important indication of civility to policymakers seeking to assimilate indigenous populations of North America and as a way to code knowledge in and on Cherokee terms.”Footnote 27

After the invention of the syllabary in its manuscript form, syllabic printing was not far behind. In 1825, the National Council appropriated $1,500 toward the combined purchase of a press and establishment of a national academy; then, in 1826, it sent Boudinot on a fundraising tour of northeastern churches to raise additional funds to close the gap.Footnote 28 With the capital secured, the National Council appealed to the ABCFM to assist in the delivery, in 1828, of an iron hand press and special types in the syllabic characters, cast at a foundry in Boston. Reams of material came off the press over the next few years, most famously the bilingual newspaper The Cherokee Phoenix, first edited by Boudinot. What is less often explored is that Cherokees used the press to print at least seventeen pamphlets in addition to the newspaper.Footnote 29

Less explored still are the Christian tracts that constituted a majority of those pamphlets. Of the seventeen pamphlets, at least eleven were Christian tracts, together comprising about a half-million pages of printed material: a hymnbook, translations of Matthew and Acts from the New Testament, a compilation of scriptural extracts in translation, a liturgical book, and Poor Sarah.Footnote 30 These eleven tracts were all printed in the Cherokee syllabary, suggesting an intended Cherokee readership. The remaining six items that did not have an explicitly Christian focus consisted of two pamphlets of Cherokee laws, two anti-removal legal opinions, a medicine book, and the Cherokee Nation's constitution. Of these, the first five were printed in English; the constitution was printed in English and Cherokee in parallel columns. The printers were planning yet more Christian publications when, in 1834, the office was forced to shut down in the lead-up to removal. However, the hiatus in Cherokee printing did not last for long: printing started up again in the west already in 1835 in Indian Territory in advance of the Trail of Tears. Eventually Cherokees founded three syllabic presses in the west, furnishing a burgeoning print culture that included newspapers, periodicals, pamphlets, and once again, several Christian tracts, including the second edition of Poor Sarah from the Park Hill press in 1843 (much more on which below).

IV. Printing Christian Tracts in Cherokee Nation

Scholarship on nineteenth-century Cherokee print media has tended to emphasize newspapers and periodicals, especially the roles of these publications in facilitating the political and social debates of the day. The literary scholar Phillip Round, for instance, has observed how The Cherokee Phoenix fostered a “counterpublic discursive space” for discussions of treaties, court decisions, legislative issues, and other political matters.Footnote 31 Scholars have also analyzed the efflorescence of newspaper and periodical publishing in post-removal Cherokee Nation and similarly focused on its political functions. In the words of Kathryn Walkiewicz, these publications constituted “an alternative, at times anti-assimilative, tactic in the continued effort to challenge imperial control,” especially as Indigenous nations pushed for statehood in the second half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 32

The Cherokees’ Christian publications, including tracts such as Poor Sarah, have not yet been fully examined by scholars. These materials are due for consideration. Not only did Cherokee-language Christian materials always constitute a substantial share of what came off Cherokee presses, but also, as I will argue, they were likewise forms of political action. The materiality of these religious texts helps to bring their politics into focus: while newspapers and periodicals engaged in political discourse in their textual content, tracts performed their politics largely through material format.

I suspect that the short shrift given to Christian tracts, despite their abundance, is partly owing to an assumption that it was white missionaries who controlled the production of those publications. Such a view makes it possible to wave away the tract printing as regrettable evidence of missionary interference, in favor of focusing on the arts of resistance wielded through media seen as more overtly political, such as newspapers and periodicals. In assessing the New Echotan printing office, for instance, one book historian concluded that, with the exception of the remarkable Phoenix, the “missionaries seem to have won out.”Footnote 33 Or, on Round's more optimistic analysis that similarly valorizes The Phoenix, “missionaries entered the community and founded a press intent on printing gospels and tracts, only to have the local community take over and begin to use the printed word for its own, largely nonreligious purposes [i.e., printing the newspaper].”Footnote 34 While it is undeniable that missionaries influenced operations in the print shop, it is inaccurate to conclude that they were really in charge, whether in establishing the press or in printing Christian materials on it.

One important thing to recognize is that the New Echotan press was the prerogative and the property of Cherokee Nation. As mentioned above, in 1825, the National Council resolved to purchase the press and put up national funds for it; they also assigned Boudinot the responsibility for additional fundraising. The Cherokees’ missionary partners at the ABCFM helped by brokering the sale and arranging for the delivery of the press and the types; they also provided a loan to Cherokee Nation toward some final expenses. After receiving the loan in 1827, Cherokee Nation repaid it in full by 1828.Footnote 35 ABCFM records are clear on the point that the establishment of the printing office was entirely, to quote the organization's 1827 annual report, “at the expense and under the direction of the Cherokees themselves.”Footnote 36 The missionaries did not own the press or provide donations for its acquisition.

Another key aspect to Cherokee printing, including Christian printing, was that Cherokee people controlled the terms. The story of the development of the metal types provides an example that illuminates the extent to which this was the case. As Ellen Cushman and William Joseph Thomas have detailed, the ABCFM had initially tried to persuade Cherokees to use a Roman script for printing, since it would be easier for missionaries to learn; the Board suggested a romanized orthographic system that had been developed by the white philologist John Pickering in collaboration with the Cherokee scholar David Brown.Footnote 37 Members of the National Council, however, wanted the types to be cast in Sequoyah's syllabary, which was already widely in use in manuscript. Upon hearing the missionaries’ proposal, the Council held firm: the syllabary or nothing. As the Board missionary Samuel Worcester put it in a missive to his managers in Boston: “If books are printed in Guess's [Sequoyah's] character, they will be read; if in any other, they will lie useless. . . of this I am confident.”Footnote 38 Ultimately, the Board relented and arranged for the manufacture of syllabic types at the New England Type Foundry in Boston, and their shipping to Cherokee Nation (Figure 2). While the Board possibly retained the matrices, the only full set of press-ready types during the pre-removal period was in New Echota. What this meant is that Cherokees possessed near-total control of what was printed in their language.Footnote 39 Thus the syllabic publications are best understood as the result of collaborations between Cherokees and missionary partners. That collaborative process favored Cherokees because of their ownership of the press and types, and their superior knowledge of the language.

Fig. 2. Cherokee matrices for typecasting. On the right is a close-up of the Ꭴ matrix. Courtesy, Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries, Mrs. J. B. (Elizabeth) Milam Collection.

Several Cherokees and white people worked together at the printing offices at New Echota and later at Park Hill, where the first and second editions of Poor Sarah were created respectively. Among them, there were four major players, who will recur throughout this article: Samuel Worcester, Elias Boudinot, John Wheeler, and John Candy. The two translators in the printing office, who nearly always worked together, were Samuel Worcester and Elias Boudinot. Worcester, mentioned above, was a white missionary for the ABCFM. Boudinot was the Cherokee statesman and editor of the Phoenix who had raised the money for the press on his speaking tour. The main pressworkers, who composed the types and operated the press, also comprised white and Cherokee people working together. In late 1826, before the printing press had arrived, the National Council had appointed the white printer Isaac Harris to oversee operations. He in turn hired John Wheeler, also white, to assist him. Soon after Harris and Wheeler began printing together in 1828, the National Council directed the office to begin employing a Cherokee apprentice, paid by the public expense, “in order to have a native printer” who would eventually become a “master at the art of Printing.”Footnote 40 The need for Cherokee pressworkers became especially urgent after Harris abruptly resigned less than a year into his post. In late 1829, the print shop made good on the Council's request and hired two apprentices to be instructed by Wheeler, namely Thomas Black Watie and John Candy (Walosudlawa [Wart-covered Frog]).Footnote 41

John Candy soon equaled his teacher. Though little biographical information about Candy exists in the content of textual sources, his rise may be traced in the evolving imprint attributions on the title pages of the New Echotan publications. On the title pages from 1830 and before, only Wheeler's name appears; in 1831, Candy's name starts to appear alongside his. What I think happened that year was that Candy was able to assert himself and prove his indispensability during an unexpected period of Wheeler's absence. Early in 1831, as part of Georgia's campaign of harassment, the governor required every white person living in the areas of Cherokee Nation that Georgia sought to take for its own to swear a loyalty oath to the state. Wheeler refused, along with many others.Footnote 42 When the Georgia militia subsequently arrested and detained Wheeler, the apprentices gamely took over printing operations. The shift in personnel prompted Boudinot to remark in a March 1831 issue of the Phoenix that the paper was now “more than ever a Cherokee paper, for the mechanical part of the labor is likewise performed entirely by Cherokees.”Footnote 43 When Wheeler returned after a few weeks’ time (he was released while awaiting sentencing), he returned not to an apprentice but to a partner. Candy's abilities as a pressworker who could work autonomously were evidenced by the title page for the 1832 edition of Cherokee Hymns, on which Candy's name appears by itself: “John Candy, Printer” (see Figure 4, below). It was the first imprint created by a Cherokee printer working alone, or at least credited alone. After that point, both Candy and Wheeler's names appear side by side on all the title pages for the rest of the New Echotan pamphlets, which is how they appear on Poor Sarah.

My point in sharing these bits of printshop labor history is to reveal how the presence of white people in the print shop did not take away from Indigenous contributions. Far from furnishing evidence for white missionary control of the press, it merely provides evidence for collaboration. The continuation of printing at various intervals in the absence of missionaries, for instance during Wheeler's incarceration, further suggests the parity of expertise and shared leadership among the Cherokee and white workers in the printing shop.Footnote 44 All this context provides necessary background to contextualize the making of Poor Sarah and the decisions that went into its formatting.

V. The First Edition of Poor Sarah (1833)

In scrutinizing the first edition of Poor Sarah (1833), the first thing to observe is that it was unusual in comparison to the other tracts that came off the New Echotan press, and not only in terms of its material format. Of the eleven Christian tracts, it was the only narrative tract, meaning that it was the only one to tell a story. It was also the sole tract to credit Elias Boudinot alone as its translator, without the name of Samuel Worcester, his usual co-translator, anywhere to be found. Finally, the tract contained unique imprint information: “Published by the United Brethren's Missionary Society at the Expense of the American Tract Society.” Most of the others did not mention the United Brethren (the Moravians) or the ATS but instead denoted that they were “Printed for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions.” An investigation into these irregularities yields crucial information for understanding the work of the individuals and institutions who contributed to (and sometimes impeded) Poor Sarah's production.

Production

Missionary records suggest that the Moravians played a foundational role in the chain of events that would culminate in Poor Sarah's publication. Sometime in the first few months of 1829, one Wilhelm Ludwig Benzien, a minister at the Moravian settlement at Salem, North Carolina, wrote to William Hallock, the corresponding secretary of the ATS, asking if the publisher might “aid in publishing tracts in the Cherokee language.”Footnote 45 Hallock's response was affirmative: while the ATS would not grant money for the publication of specific tracts, it could help by giving a donation to the Moravians, who could convey the funds to the ABCFM for use in the print shop. Hallock even suggested a few options: “Poor Sarah, Rewards of Drunkenness, Swearer's Prayer, &c.”Footnote 46 Enthused by the positive response, the directors of the two Moravian missions in Cherokee Nation—Gottlieb Byhan at Springplace and Heinrich Gottlieb Clauder at Oochgeelogy—then took the question to Elias Boudinot and Samuel Worcester. Would they be interested in printing a narrative tract in Cherokee?

The answer from Boudinot and Worcester was divided. In Byhan's words, “the former is willing to print the Tracts, but the latter is causing some difficulties.”Footnote 47 We do not learn from the missionary records what Boudinot specifically thought; we do hear an earful from Worcester. That Worcester was causing difficulties was a euphemism for his utter refusal. Worcester described to his superiors that when a pair of Moravians from Salem visited him with a proposal to print tracts, he brushed them off, claiming that his partner Boudinot was simply too busy to take on more work.Footnote 48 Determined not to be refused so easily, Clauder, the local Moravian missionary at Oochgeelogy, paid yet another visit to Worcester. This time, Clauder offered to compensate Boudinot for the work. An increasingly aggrieved Worcester said no, explaining that if Boudinot were to take on a tract project, it would interfere with the ABCFM's interests in printing the Bible, thus violating the missionaries’ tacit principle of noninterference with one another's efforts.Footnote 49 That put an end to the conversation. Byhan summarized the situation diplomatically: there were “more difficulties printing the tracts in the Cherokee language than they originally expected.”Footnote 50 Discussion about the “situation concerning the Tracts” fizzled out in both ABCFM and Moravian records by late summer 1829.Footnote 51

The idea was picked up again nearly three years later in late summer 1832 as several enabling circumstances came together, namely: Boudinot's time, Worcester's absence, and the availability of external funding. The first factor that contributed to the comeback of the tract project was Boudinot's sudden abundance of time. Under pressure from Principal Chief John Ross and the National Council for his unpopular stance on removal (he had begun to see it as inevitable, and advocated for negotiating it on the best terms), Boudinot had just resigned from his editorship of the Phoenix and been replaced by Ross's brother-in-law.Footnote 52 This loss, though disastrous for Boudinot's career and ability to communicate with his fellow citizens, enabled Boudinot to turn to other priorities such as the tract translation that he had discussed with the Moravians years before. As Clauder reported in August 1832, “Mr. Boudinott is no longer editor of the Phönix now, and he wants to spend his time translating.”Footnote 53 Boudinot and Clauder moved quickly in laying out plans and by October had selected the title. The duo first decided that they ought to choose among the ATS tracts available to them, and Clauder quoted Boudinot as pointing out that “something of the narrative kind would be easiest translated & increase the desire of reading among the Cherokees.”Footnote 54 Boudinot went on to suggest the “well-known tract, Sarah, the Poor Indian Woman, for translation.”Footnote 55 Clauder deferred to his colleague's expertise, admitting that Boudinot “knows the taste of the Cherokees better than I.”Footnote 56

The selection of the title may not have presented a particularly difficult decision. At the time, Poor Sarah was the only tract in the ATS's catalog about an Indigenous person. If Boudinot wanted to translate a narrative tract about Indigenous Christianity that he hoped might have resonance in his community, he did not have other source texts available. Boudinot might also have warmed to Poor Sarah for personal reasons, since the story took place in Connecticut, not far from where he went to school and met his wife. Whatever the exact motivations may have been, Boudinot began to work on the translation in December 1832.Footnote 57

The second circumstance that facilitated the translation of Poor Sarah was the extended absence of Worcester, who had been averse to the project. Worcester was incarcerated in a Georgia prison during the time that Boudinot and Clauder concretized their plans over the summer and fall of 1832. As mentioned above, in March 1831, the governor of Georgia had forced all white people living on the Cherokee lands that Georgia sought to annex to swear an oath of allegiance to the state. This event affected the operations of the print shop: Worcester and Wheeler both resisted and were arrested, jailed, and in September sentenced to four years. At sentencing, Wheeler, along with most of the other whites in his position, relented and swore the oath. Worcester, however, held out for much longer.Footnote 58 Altogether the missionary was imprisoned for sixteen months from September 1831 through late January 1833 (when he too finally relented). This meant that Worcester was not present when Clauder and Boudinot hatched their plans in summer and fall 1832. Nor was he there in December as Boudinot worked on the translation. Boudinot was thereby enabled to produce a tract that he might not have had the chance to pursue with Worcester underfoot.

Worcester's absence also enabled Boudinot to translate in the ways Boudinot saw fit. More typically, Boudinot and Worcester collaborated on the New Echota translations. As mentioned above, their names appear side by side on nearly all other Cherokee tracts from that period.Footnote 59 Presumably, each was stronger in certain languages involved in their process: Boudinot in Cherokee and Worcester in Greek (their main source language for the New Testament translations).Footnote 60 Poor Sarah, however, is the only tract from the pre-removal period that Boudinot translated alone. Poor Sarah thus offered Boudinot the rare opportunity (outside some translations for the Phoenix) to flex his skills independently. That autonomy made a significant difference in the final textual product. The Cherokee language instructor J. W. Webster observes that among the New Echota publications, Boudinot's translation of Poor Sarah is characterized by a “sophisticated writing structure” and displays a command of the complexities of Cherokee grammar. The other imprints from this period, all collaboratively done with Worcester, tend toward simplification in grammar and contain more errors.Footnote 61

Finally, the third circumstance that enabled the production of Poor Sarah was the availability of external subsidies from both the ATS and the ABCFM. To start with the latter, in November 1832, the ABCFM's secretary David Greene wrote to Boudinot to share the news that the organization recently voted to furnish him with an annual salary of $300 to translate “narrative tracts”—i.e., not scriptures—full time.Footnote 62 This offer directly contravened Worcester's earlier wishes, who had gone to great lengths to preserve Boudinot's skills for scriptural translation alone. Perhaps the Board decided to override Worcester, possibly in response to a request from Boudinot himself, who, as we know, had already expressed desires to turn toward translating tracts. Boudinot had also already selected the ATS's Poor Sarah for a translation project. He had further indicated that he intended to do it “without payment,” according to Moravian correspondence.Footnote 63 While Boudinot may well have translated Poor Sarah without the Board's support, doubtless it was a welcome offer after losing his editorship some months before.

Material assistance from the ATS was another contributing factor to the production of the Cherokee Poor Sarah. One of the most important forms of support was the gift of the physical woodblock, which pictures Sarah outdoors giving grapes to a small crowd of white children. The ATS had used it to illustrate its earlier edition of the title. Soon after Boudinot had selected Poor Sarah, Clauder wrote to the ATS to request the use of the woodblock; Clauder and Boudinot may or may not have known that the ATS did not need the block anymore, as the publisher was in the process of replacing all its old images cut by Harlan Page—who signed the Poor Sarah illustration with his P, visible in the bottom righthand corner, to the right of the boy's left foot—for updated work. The ATS granted the request, and the block arrived in Cherokee Nation by mail sometime in late 1832 or early 1833.Footnote 64 Parenthetically, while Clauder did not specify whose idea it was to obtain the block, evidence from the Phoenix offers a basis to suppose that Boudinot was behind it. In an issue from December 1829, Boudinot reprinted a letter from a missionary at Sault de St. Marie who claimed that illustrated tracts in Indigenous languages furnished the best tools for communicating Christian knowledge. Among the publications available at his station, the missionary said, those “which are illustrated by engravings, have made by far the most deep and lasting impressions.”Footnote 65 While Boudinot's distribution of this statement in 1829 is not itself dispositive of his intentions in 1832, it does indicate that Boudinot was alert to the powers of images in printed religious materials.

The imprint information, which describes the tract as published “at the expense of the American Tract Society,” seems to suggest that the ATS played a larger financial role beyond just offering the block. Piecing together the details from various accounts (from the Moravian manuscripts, the ABCFM manuscripts, and the printed records from the ATS [the ATS's manuscript archives are not extant]), it appears that the ATS did offer funding for the Cherokee Poor Sarah, but it was after the tract had already been planned, translated, and published.

The Moravians had decided to appeal for monetary aid from the ATS again, this time without involving the incarcerated Worcester in their plans. In early 1832, Clauder caught wind of how the ATS was preparing to make a $200 donation to all Moravian foreign missions (which included outposts in places like Greenland and Suriname). After “thorough consideration and discussion with Elias Boudinot,” Clauder decided to ask his superiors if some of those funds might be diverted to the Cherokees to cover the expenses of printing a tract.Footnote 66 He observed that Boudinot had firsthand experience of tracts’ effectiveness, quoting him as saying that “a Cherokee tract has done more good in a short time than 4 missionaries can accomplish in a long period of time.”Footnote 67 The tract that Clauder and Boudinot had in mind for financing at the time was not yet Poor Sarah, though. Instead, they were hoping to cover the costs of a twelve-page tract that they had already printed and for which they had possibly gone into debt. This was a compilation of various extracts from scripture, including pieces from the books of Genesis, Exodus, Luke, and John. The printers were in a tight spot: they had counted on the American Bible Society (ABS) to reimburse them for some of their expenses for that project, but the ABS reneged, claiming that the organization could not support a publication did not translate any single book of the Bible in full.Footnote 68 On presenting the situation to the ATS, the society agreed to help in a pinch. ATS financial records from 1832 note that the publisher appropriated an additional $44, on top of its planned donation to the Moravians, to subsidize supplies for “an edition of 3000 of a scripture Tract of 12 pages, in Cherokee.”Footnote 69

That initial donation for the “scripture Tract” set in motion a patronage relationship between the ATS and the Cherokee printers, and set the terms that governed that relationship thereafter, including for the 1833 Poor Sarah. In short, it was a reimbursement system. The printers were to ask for financial assistance not for proposed publications, but rather after the fact, once the printers could provide detailed accounts for their expenditures.Footnote 70 The ATS imposed a stipulation on these arrangements: if the organization made a contribution for a particular title, then the Cherokee printers were compelled to give away that title for free. If the printers sold any copies, they were required to credit back the ATS for the copies sold.Footnote 71

Poor Sarah received funding from the ATS according to this system. Though Boudinot translated Poor Sarah in late 1832 and the printers prepared the tract for printing in early 1833, there is no indication in the ATS's annual reports for 1832 or 1833 that the society had committed funds for the project. It was only in 1834—over a year after publication—that the ATS remarked that it approved support for the Cherokee-language Poor Sarah.Footnote 72 This timeline is corroborated by ABCFM records, which noted a donation of $100 from the ATS on April 14, 1834, which must have been for Poor Sarah. Footnote 73 Owing to this system of delayed assistance, it is safe to say that the ATS's role was limited to that of distant patron that did not exert creative control. It also suggests that the line of attribution on the title page of Poor Sarah, crediting the publication as done “at the expense of the American Tract Society,” must have referred only to the gift of the woodblock, and perhaps a hoped-for future grant. No money had yet exchanged hands when that line was printed.

The printing itself took place in early June 1833. At least five people were involved in the process. In addition to Boudinot who was certainly in attendance, Candy and Wheeler performed the mechanical labor of composition and imposition, as reflected in the imprint information (“J. F. Wheeler and J. Candy, Printers”). Of the missionaries, Clauder's correspondence further reveals that Clauder was present for one and a half days to “finish the tract” and that Worcester contributed his “assistance,” though their exact activities are left ambiguous.Footnote 74 Though it seems plausible that all five would have contributed creatively to the tract's design, it remains impossible to determine the nature and scope of influence from each person with the available sources. In reference to Poor Sarah, I will discuss all five members of this group as “the printers” (or sometimes “Boudinot and the printers” to acknowledge Boudinot's leadership), with the assumption that the creative choices that characterize the tract's format came collectively from the group. With this caveat in mind, the elements of the printers’ choices now may be parsed to show their close fidelity to Anglo-Protestant tracts, and the ATS prototype in particular (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. On the left is the prototype published by the ATS: Poor Sarah; Or, The Indian Woman (New York: American Tract Society, [1825–1827]), 10.5 x 17.6 cm (12mo). Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society. It may be compared to, at right, the New Echota edition: Poor Sarah; Or the Indian Woman (New Echota: J. F. Wheeler and J. Candy, Printers, 1833), 9.9 x 17 cm (12mo). Courtesy, Ayer Collection, Newberry Library, Chicago, IL.

Formatting Resemblances

The scale of the Cherokee tract is the first hint that the printers were modeling their tract on the ATS version. The dimensions, as may be seen just below, are nearly the same as those of the ATS's tract, within a centimeter of one another in both length and height. To deploy a bibliographical term, both the ATS and the New Echota tracts were printed in 12mo (duodecimo) format. Though I am using “format” more generally in this article to refer to all sorts of material characteristics of a media object, in the field of bibliography (the technical study of books as material objects), format has a narrower meaning that refers to the number of leaves produced from a sheet of paper in the printing press. It is that narrower sense that I am invoking here: the format of 12mo or duodecimo indicates that the printer printed twelve leaves to a sheet, compared to, for instance, eighteen leaves to a sheet for 18mo, and twenty-four for 24mo.Footnote 75 Though bibliographers would hasten to add that format does not always neatly correspond to the scale of the resulting publication, owing to the fact that full sheets could have different dimensions, for our purposes they do: the higher the number denoting the format, the smaller the scale of the imprint.

The duodecimo format of the 1833 Poor Sarah made it exceptionally large among the Cherokee imprints. It not only dwarfed its second edition from Park Hill in 1843; it was also unusually large relative to all the other Christian pamphlets from New Echota at the time, almost all of which were scaled to a 24mo format. Below is a view of Poor Sarah, on the right, positioned at scale next to the more representative Christian tracts from New Echota, namely the Gospel of Matthew and Cherokee Hymns (Figure 4), which were small and text-only. Matthew is scaled to 24mo, which was the most common format of the Cherokee-language Christian pamphlets, so much so that we might call it the “standard Cherokee format.” Hymns was one of two editions of the hymnbook scaled slightly larger at 18mo. The only other Cherokee-language Christian imprint from New Echota that was as large as Poor Sarah was the Moravian Church Litany, also in duodecimo.Footnote 76

Fig. 4. At left, Gospel of Matthew, trans. S. A. Worcester and E. Boudinot, Second Edition (New Echota: John F. Wheeler, Printer, 1832), 7.4 x 12 cm (24mo), Courtesy, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library; to its right, Cherokee Hymns, trans. S. A. Worcester and E. Boudinot, Third Edition (New Echota: John Candy, Printer, 1832), 9 x 14.6 cm (18mo), Courtesy, Library of Congress. By contrast, to the right of the ruler, the Newberry's Poor Sarah (1833) is 9.9 x 17 cm (12mo).

The question is why the printers constructed Poor Sarah in duodecimo, which made it exceptionally large among nearly all the other Cherokee-language Christian pamphlets. It may be tempting to suggest that they printed it that way simply because they expected the anticipated ATS funding to reimburse their expenditures for the increased amount of paper it required. But the ATS money was not guaranteed. Moreover, the printing office printed several non-subsidized pamphlets in the larger duodecimo size, including every single one of its six English-language pamphlets (two legal opinions, two law books, a medicine book, and the bilingual constitution). These all required a great deal of paper. The 48-page lawbook, for instance, used two full sheets for each copy, versus the 12-page Poor Sarah, which took only half a sheet each. The issue was not if the funds existed to print duodecimos, because it is clear they did, but rather how the funds would be distributed to achieve the printers’ desired formatting goals across various projects.

The more compelling answer is that the Cherokee printers were deliberately emulating Anglophone scale conventions in their formatting of Poor Sarah. Duodecimo was the Anglophone book trade's most common format for religious tracts and other sorts of pamphlets in the earlier part of the nineteenth century. By contrast, publications in 24mo—the format of most of the other Cherokee-language texts—were typically considered miniature by the trade and were more associated with children's literature.Footnote 77 By formatting the Cherokee-language Poor Sarah in duodecimo, then, the printers were bringing their tract into scalar alignment with the format of not only the ATS prototype, but also with most other English-language tracts and pamphlets printed in the United States. What I wish to emphasize here is that when Candy and Wheeler were imposing the types on the press in preparation to print Poor Sarah, they broke from the shop's usual patterns. They did so in a way that was consistent with the expectations of English-reading audiences but that departed from most of its other smaller tracts designed for their Cherokee readers.

The printers similarly imitated the ATS prototype in the elements of typography and layout. Moving from the top to the bottom of the page, starting at the subtitle, the printers used a morphologically similar italicized typeface, down to the swashes on the tails of the strokes (Figure 5). As for the illustration, the printers took the block sent from New York and positioned it in the same location. They too inserted a pull-quote caption right below it (Figure 6). The printers even took special care to set the imprint information, at the end of the title page, in a triangular formation (Figure 7), another feature of the ATS house style (which was itself a citation of the shape of colophons in medieval and early modern printed texts and manuscript codices, intended by the ATS to invoke the prestige of those older textual traditions).

Fig. 5. Close-up of typography on the subtitle of the ATS edition, at the top, compared to the New Echotan edition, below. Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society and the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK.

Fig. 6. Close-up on the pull-quote captions of the ATS edition, on top, and the New Echotan edition, below, which reads ᏀᏍᎩ ᏅᏓᎦᎵᏍᏙᏗᏍᎬ ᎤᏂᏣᏛ ᏗᏂᏲᎵ ᎬᏩᎨᏳᎯᏳ ᏂᎦᎵᏍᏗᏍᎬᎩ (trans., There were many children that came to love her.) Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society and the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK.

Fig. 7. Cropped close-up on the sets of triangular imprint information on both the ATS and the New Echotan editions. Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society and the Newberry Library, Chicago, IL.

Only one modification purposively distinguished their tract from its prototype. Someone in New Echota customized the woodblock by nicking three dots into the block's surface, which printed as three white absences radiating upwards to the left of Sarah's head (Figure 8). The decoration is visible in all the Cherokee copies I have examined, and in none of the ATS copies, suggesting that the modification was done in New Echota. The pattern is not something that would have occurred in ordinary circumstances of wear and tear. Beyond this delicate decoration, which, one could speculate, may have operated as a sort of signature mark, all the resemblances indicate that Boudinot and the printers had the ATS prototype positioned in front of them and emulated it closely as they prepared their edition. The next question becomes how readers and owners of the printed product would have responded to these forms of close visual imitation.

Fig. 8. Close-up, at right, showing the modification to the woodblock on the Cherokee edition, which printed as the three absences radiating upwards from the left of Sarah's head. At left, the ATS illustration before the modification was made. Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society and the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK.

Distribution and Reception

The Cherokee-language tracts that came off the New Echota press circulated to two audiences: first, to white people outside Cherokee Nation (who I will call “beholders” and not readers, since they were not reading the text), especially missionaries and their friends; and second, to Cherokee readers within the Cherokee community. Given their formatting choices, how might the printers of Poor Sarah have expected each audience to respond? To address the question of the white beholders first, my argument is that the printers intended that when white beholders looked at the tract, it would feel familiar, and moreover that it would be legible as a tract on the model of the millions of tracts that the ATS had been circulating at the time. Poor Sarah would thereby serve as incontrovertible material evidence of Cherokee Christian civilization. The format of the tract says: this is what a tract looks like; ergo, we, Cherokees, are just like you.

The political potency of the tract's format hinged on how formats operated as forms of public knowledge. For the format to work, it required a beholder to recognize its characteristics and distinctiveness. As McGill has remarked, today one can detect from a distance of twenty feet if a book is an encyclopedia or a novel or a comic book. As she puts it, “You know these books’ likely genres by their size and shape, by publishing conventions that you've learned to associate with these texts’ roles in culture.”Footnote 78 Nineteenth-century white Protestants were likewise habituated to the meanings of various formats in their media environments, as in, for instance, the practice of displaying a family Bible in a parlor. That practice presumed a general cultural recognition of the formatting elements correlated with family bibles, such as being large, thick, heavy, leatherbound, and so on.Footnote 79 Likewise, the format of Poor Sarah would have been recognizable as an ATS-style tract to people familiar with tracts.

Format's power to encourage certain patterns of recognition is a subtle sort of power. It is not a particularly “hard” technique, so to speak, especially compared to other, more overt ways of changing minds and compelling behaviors. It is not like throwing someone in jail or passing a law. However, format possesses some special qualities that made it useful to Cherokees in the context of settler colonialism and Indian Removal. For one thing, it is speedy. Just as beholders familiar with family bibles could identify one such Bible instantly, those familiar with Anglophone-style pamphlets would have quickly perceived Poor Sarah as a member of that class of objects. For another thing, it did its work before the beholder had a chance to think about it. That is to say, the object would have hit white beholders on a precognitive or tacit level with the obvious fact of Cherokee Christian civilization and acculturation to US Protestant norms. It is not that white beholders necessarily reasoned their ways to that conscious proposition; the point is rather that, given the ways that whites were habituated to certain ways of viewing texts at the time, to behold the tract at all, the printers devised, was to accept its political message that supposed the equality of whites and Cherokee Christians. The printers’ technique in Poor Sarah may be understood as an application of Boudinot's stated theory seven years prior in Address to the Whites (1826), where he claimed that the truth of Indigenous civilization “needs not the display of language” and “needs not the power of argument.”Footnote 80 Poor Sarah did not require these discursive tools to have an impact, for its artifactual qualities attested to Cherokee civilization before anyone even turned its pages. The speed and subtlety of media format made it useful as a political tool, at a moment when the stakes could not have been higher for Cherokee Nation.

At the same time, Christian tracts also reached a Cherokee audience. The Moravian records speak to the specific distribution routes of the 3,000 copies of Poor Sarah in particular. First, the Moravian missions in Cherokee Nation received several copies, which they distributed among their members. A few months after publication, Clauder testified to how “the little tract Poor Sarah is frequently read by the Cherokees and hopefully with blessings.”Footnote 81 He also described reading aloud from it during services.Footnote 82 In addition, fully one-third of the edition was sent west to Arkansas territory. According to Clauder, Worcester had apparently “asked for 1,000 copies to send to Arkansas, and I gave them to him.”Footnote 83 This passing comment indicates that already in spring 1833, Worcester had resolved that the tracts would do more good in Indian Territory than in Cherokee Nation, which he must have believed would soon cease to exist in the east (in line with the thinking of Boudinot and other Treaty Party members). One thousand tracts would not only supply the population of so-called Old Settler Cherokees who were already leaving for the west, but also could be kept for the Cherokees who, Worcester presumed, would be migrating there over the next decade.

Beyond the allocations to the Moravians and to the Arkansas settlers via Worcester, the remaining copies of the edition would have been sent along more established Cherokee Nation tract distribution channels. Textual evidence reveals several modes of distribution before removal. One common occurrence was missionaries passing out material to Cherokee readers for free. Clauder, for instance, happily described a Moravian church service when he found many “willing takers” of the texts.Footnote 84 It is likely that the other missionaries in the Nation representing the other denominations also procured tracts from New Echota for this purpose and distributed them similarly. In one letter from the corpus of ABCFM manuscripts, the Board's secretary David Greene suggested, with some reluctance, that the New Echotan printers probably ought to be magnanimous and share copies, without charge, with Cherokee Nation's Methodist and Baptist missionaries (even though their denominations were in competition with the ABCFM), who could then share them with a wider circle of Cherokee readers.Footnote 85

At other times, the initiative to procure tracts came first from communities of Cherokee readers who appealed to missionaries for their assistance. This dynamic may be glimpsed in a letter to Boudinot from the pastor Isaac Proctor, reprinted in the April 1828 edition of the Phoenix, describing how the members of his ABCFM mission at Carmel urged him to write on their behalf: “They are very anxious to have some parts of scripture in Cherokee, or any Cherokee tracts. I understood, the other day, that you were about to get the Gospel of Matthew printed. Do let me know by next mail how soon we can obtain it. Many copies are wanted in this place, and I have been requested to write for them.”Footnote 86 In response, Boudinot observed that “similar applications with equal earnestness have been made from other parts of the Nation, and we are sorry not to be in a condition to meet the demands of our press.”Footnote 87 He pledged to do better: “Exertions, will, however, be made to supply our demands.”Footnote 88 Without presuming that the reading tastes of Proctor's congregants were representative of Cherokees generally, this episode shows that there was desire for Cherokee-language Christian tracts from the New Echota shop, to the extent that some readers appealed to missionaries for help in their acquisition.

Another way that readers received Cherokee-language tracts was through Cherokee Nation's tract and book societies, which were dedicated to distributing them both through sale and for free. These included the Methodist Tract Society of Cherokee Nation (founded in 1828), the ABCFM's Brainerd Cherokee Book Society (in 1829), and the Baptist-affiliated Valley Towns Tract Society (also in 1829).Footnote 89 Evidence for these societies may be found, again, in the pages of the Phoenix, where each of the above three announced their formation and reprinted their charters. It appears that these societies were administered on a similar model as the evangelical benevolent societies in the United States. The constitution of the Brainerd Cherokee Book Society, for instance, indicates that one could become a member through a donation of any amount and that those funds would be used to purchase “Religious Books or Tracts in the Cherokee language for sale or gratuitous distribution”—that is, for resale to interested readers, or as charity to needy community members.Footnote 90 The idea was that the donations would subsidize tracts and books for those who could not pay. Additionally, any member who gave a donation would receive back half the value in publications for his or her own uses.Footnote 91 Since Poor Sarah received ATS funding, it is likely that this title was always given away for free, as per the ATS's stipulations described above, even if distributed through these book societies.

In one documented instance, a book society hired a Cherokee man to engage in itinerant tract distribution. Details may be found in the missive by Proctor, mentioned above, who described the work of two societies organized at the ABCFM missions at Carmel and Hightower (neither of which announced themselves in the Phoenix, indicating that there may have been even more societies that did not leave paper trails): “The Cherokee members of this church, and those of the church at Hightower, have formed societies to hire a Cherokee brother to go as their missionary into those dark towns north of us, to carry bibles, tracts, and hymnbooks. We therefore want to know when we can obtain all these, and what will be the prices.”Footnote 92 On his journeys, perhaps the itinerant sold the tracts; or, in the case of subsidized tracts like Poor Sarah, or if the societies had already paid New Echota for the tracts as Proctor suggested, he may have dispensed tracts to the denizens of these towns for free, as charity, on the model of benevolent tract distribution associated with the American Tract Society and similar organizations.Footnote 93 While it is impossible to know how recipients experienced this Cherokee missionary in their midst without more evidence, it is plausible that many would have accepted his gifts even if they had little interest in, or were hostile to, the Christian religion, simply because he carried printed material in their language. In the “dark towns”—presumably so-called because they were far away from churches and had a high proportion of residents unaffiliated with a mission—publications would have been a novelty and perhaps desirable for that fact alone. The above evidence, though fragmentary, demonstrates that Christian tracts like Poor Sarah would have been read by Cherokees, including those who were affiliated with churches and those who were not.

The Moravians also left behind records that document how Cherokee people read and engaged with tracts. Practices of reading included reading tracts alone; singing from printed hymnals; reading tracts aloud in church services; and copying manuscript versions of borrowed printed texts for personal use.Footnote 94 While the sources do not discuss extensively how Cherokees experienced these texts, there are scattered examples. The mission member Christian David Watee kept Cherokee tracts on a chair near his bed and testified that “I spend most of my time with them and receive much comfort from them.”Footnote 95 Another young man named Archibald, not yet a member of a mission, became so absorbed in the Cherokee-language Gospel of Matthew that he continued to read it “while he was walking and standing,” and, with the book still open in his hand, he promised to return to the mission the following Sunday.Footnote 96

Readers of Cherokee-language tracts like Archibald and Christian David, who had spent time at a mission, would have also had access to English-language tracts including ATS tracts and thus would have been familiar with their formats. Some had probably seen or read the ATS's Poor Sarah before they ever encountered the 1833 New Echotan edition. According to ATS records, between 1829 and 1833, the publisher had donated approximately 4,100 tracts to Cherokee Nation, mediated through missionaries including the Moravians, the ABCFM, and the Baptists.Footnote 97 Presumably, ATS tracts were distributed in the same ways that Cherokee tracts were distributed, as discussed above, that is, through missionaries and possibly through the tract and book societies. Though the ATS records do not specify which titles were sent, Poor Sarah was certainly among them because Boudinot had selected it among the lot of ATS titles available to him.

This larger context of Cherokee readership of ATS tracts shows that in producing their own edition of Poor Sarah, Boudinot and the printers were wagering on a recognition of its format not only among white beholders but also among Cherokee readers. Cherokee readers would have been aware that the Cherokee Poor Sarah was not only exceptional among the 24mo imprints that more typically came off New Echota's press, but also exceptional for its studied imitation of the ATS version.

My sense is that Boudinot and the printers were asking something different from these Cherokee readers than they were from their white audience. Above, I argued that for white beholders, Poor Sarah conveyed its message of Cherokee acculturation precognitively, in an instant. By contrast, for Cherokee readers who had more recently encountered Anglo-Protestant tracts, particularly ATS tracts including Poor Sarah, the ATS's house-style format would have been still somewhat foreign and more prone to grab attention. For these readers, then, the Cherokee Poor Sarah would have been liable to spur conscious reflection on the similarities between it and its ATS prototype and others like it. In other words, Boudinot and the printers were asking their Cherokee readership to imagine and conduct themselves as if they were the sort of people who read Anglophone-style materials. The format says, please be—act like and feel like—an acculturated Protestant subject. Short of that, at least play the part for now.Footnote 98 While Poor Sarah taught whites to understand that Cherokees were already like them, it prompted Cherokees to simulate the feelings and practices of white Christians.

VI. The Second Edition of Poor Sarah (1843)

If Boudinot's 1833 Poor Sarah was formatted to display acculturation to white Protestant norms, more and less explicitly for Cherokee readers and white beholders, what was the goal of the second edition in 1843, printed in Park Hill? That edition presents a thoroughly revised format in terms of dimensions, layout, and typography (Figure 1 and 9).

Fig. 9. The copy of Poor Sarah, in its original stab-stitched binding and white paper wrappers, laid by John Ross in the cornerstone of Cherokee Female Seminary in 1847. Librarians opened the contents of the cornerstone in 1989. 7.5 x 12.4 cm. Courtesy, Northeastern State University Archives, Tahlequah, OK. Photograph by Blain McLain.

The process of answering the question begins with a recognition of the drastic changes in the Cherokees’ political and geographic circumstances after removal. By the time of the publication of the second edition, Cherokees had lost their ancestral lands and the majority had endured a violent forced migration over 1838 and 1839 along the Trail of Tears to Indian Territory (in present-day Oklahoma). In this time of upheaval, Cherokees renegotiated their relationship to Christianity. In his Cherokees and Christianity, William McLoughlin argues that Presbyterian and Congregationalist missionaries associated with the ABCFM lost standing in the Cherokee community given their ultimately disappointing roles in the fight against removal (more on which below), and on account of their relationships to Treaty Party members such as Boudinot. McLoughlin traces how, in this milieu, western Cherokees developed what he termed a “new syncretic religion” that merged Christianity with precontact practices including the Green Corn dance, ball plays, and traditional medicine.Footnote 99 He points to how Cherokees in the 1840s embraced in higher numbers the Baptist and Methodist denominations, which in Cherokee Nation tended toward acceptance of religious adaptation more than did the ABCFM and the Moravians, as well as the development in the 1850s of the Keetoowah Society, a Cherokee civic and religious association that supported religious hybridization.Footnote 100

With these changes in mind, my argument in this section is that the printers in the western Cherokee Nation's print shop—now under the stronger direction of John Candy, and without Elias Boudinot's involvement—altered Poor Sarah to do different work. No longer did the tract communicate its Christian civilization to a white audience in a way that such an audience was primed to recognize. In fact, the tract no longer specially appealed to white observers at all, as Boudinot had done deliberately. Nor did the Park Hill printers care to nudge their Cherokee readers to see themselves as acculturated reading subjects, at least not in the extreme sense pushed by Boudinot pre-removal. Instead, the Park Hill printers were creating a new tract tailored to the changing needs of Cherokee readers, who were reshaping Christianity in ways that did not foreground acculturation—particularly acculturation to elite Anglo-Protestant norms embodied in institutions like the ATS and the ABCFM. It is beyond question, as many scholars have explored, that Cherokees continued to use acculturation as a strategy in the years following removal and through the nineteenth century.Footnote 101 My point is that owing to the painful truth that acculturation had not succeeded as a strategy to stay on the land, no longer did the printers pursue religious acculturation aggressively through format. Instead, they crafted the materiality of their publications to turn toward the development of Indigenized Christian forms to serve the Cherokee community.

Removal and the Reestablishment of Printing in Indian Territory

Some brief history of the impact of removal on printing, the printers’ roles in removal, and the reestablishment of the press in the west will help contextualize an analysis of the second edition. The threat of removal was looming large around the time that Boudinot was finishing up his translation of Poor Sarah in December of 1832. Though Cherokee Nation had technically won its case Worcester v. Georgia (1832)—which compelled Georgia to recognize Cherokee sovereignty—the newly reelected Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the ruling. Cherokee leaders and their missionary partners, most of all Worcester, initially fought to compel Chief Justice John Marshall to provide for its implementation. However, hopes for that outcome were extinguished by January 1833, when, citing threats of Georgia's secession and civil war, the missionaries decided to give it up. At that point, Georgia released Worcester from prison, and he returned to the print shop.Footnote 102 In the wake of this defeat, the Nation fell on even harder times as the US withheld treaty-brokered annuities through 1833. In 1834, printing came to a stop in the absence of those funds. The possibility of restarting was lost when soldiers of the Georgia Guard illegally rushed the print shop and “forcibly seized the press, types, books, papers, and other materials pertaining to a printing office,” as John Ross recounted later.Footnote 103 The military assault on the press and types may be taken as a form of recognition of the political power of Cherokee printing.

The point of no return came in late December 1835. Boudinot and other members of what was known as the Treaty Party, prominently Major Ridge and his son John Ridge, met with representatives of the US government and signed the removal treaty, called the Treaty of New Echota. They felt that they had no other option. The Trail of Tears that followed, over 1838 and 1839, caused the deaths of up to half of the eastern Cherokee population.Footnote 104 To many Cherokees, especially those associated with the opposing Ross (or National) Party, the action of Boudinot and other Treaty Party members constituted a betrayal. Today, the interpretation of these events remains divisive and subject to ongoing revision among scholars and Cherokee citizens.Footnote 105