“Lord, is this the time when you will restore the kingdom to Israel?”

—Acts 1:6Prophecies are for the distressed.

Three separate stories from China's ethnic frontiers in Southeast Asia reveal a common pattern in the unexpected, spirited growth of Christianity in the region. All three began at the dawn of the twentieth century. In each of these cases, despite the apparent expansion of Western power and missions in the area, conversion to Christianity was evidently not a grudging surrender to a conquering foreign faith—the “most humiliating” of all forms of cultural defeat, as Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. maintainsFootnote 1—but an exuberant, communal rush toward fulfillment of indigenous, pre-Christian prophecies. The historical agency of the hill peoples, often overlooked or dismissed, was never in question.

I. The Birth of Ahmao, Lahu, Wa, and Lisu Christian Communities

The first of these stories is from western Guizhou province. In 1903, J. R. Adam of the China Inland Mission in the town of Anshun ran into some Ahmao hunters dressed in “strange garments [. . .] carrying cross-bows and arrows.” Known to the Han Chinese as Dahuamiao, or the Great Flowery Miao, a subgroup of the Miao (Hmong), they were the poorest, landless “raw Miao,” who lived on hunting and gathering in the wild mountains. Adam won them over with his friendliness and hospitality and, according to Chinese sources, later helped them recover a wild boar that had been forcibly taken away by the locals, leveraging the official protection he enjoyed under the Treaty of Tianjin (1858). Words spread among the long-oppressed Ahmao, and an old man proclaimed that the “Klang-meng”—the “Miao King”—had been found in Anshun.Footnote 2

From Anshun the gospel was brought to Weining prefecture, the heartland of the Ahmao, deeper into the mountains of western Guizhou, where 40,000 of them were reportedly living. Because of its relative proximity to Zhaotong in Yunnan province, Adam referred the Miao inquirers to a fellow missionary, Samuel Pollard of the British Bible Christian Mission, then stationed there.Footnote 3

Pollard had arrived in Yunnan in 1888 and, like Adam, had seen his work languish among the Han dwellers in the valley, but it sprang to life in 1904 with the coming of the Ahmao—first in tens and twenties, then in sixties or seventies. “At last, on one special occasion, a thousand of these mountain men came in one day! When they came, the snow was on the ground, and terrible had been the cold on the hills they crossed over.. . . Once we counted six hundred people staying the night with us.”Footnote 4

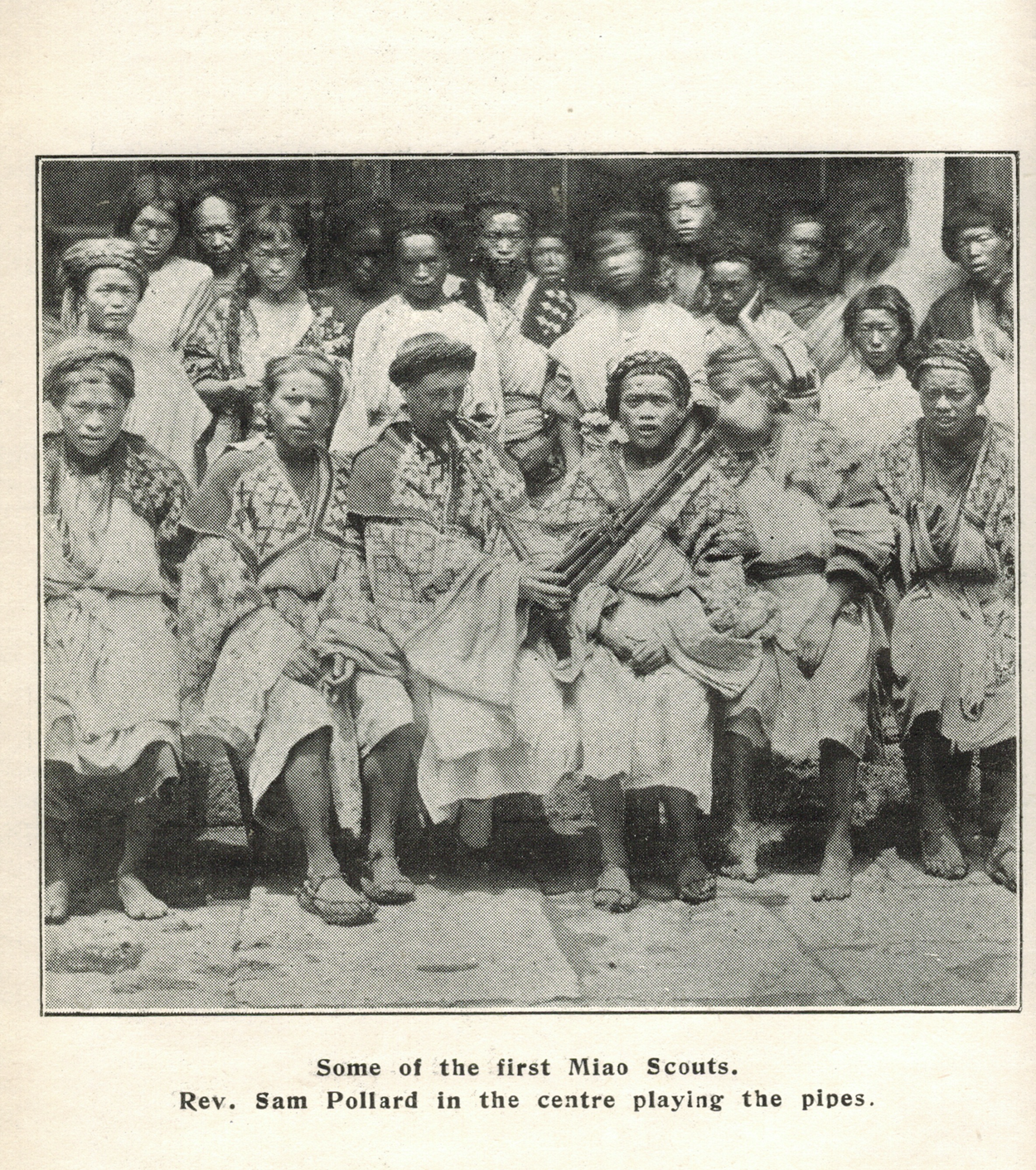

They came—“their faces brightened up,” Pollard noted—for a reason he only dimly understood at the time.Footnote 5 “When we first turned to the faith, we did not understand the teachings of Christianity,” wrote Wang Mingji, whose family was among the earliest Ahmao converts that Pollard made in 1904–1905. “We heard that Heaven had given us a Miao King in Anshun; we also believed that Pastor Pollard of Zhaotong was able to deliver the Miao people from tyranny into freedom”Footnote 6 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Samuel Pollard playing the lusheng pipes brought by the Miao inquirers, c. 1904. The instrument was used in the annual “Feast of Flowers” festival featuring dances that reenacted the Miao's ancient exodus from North China. Source: Sam Pollard, The Story of the Miao (London: Henry Hooks, 1919).

An important means of that foretold deliverance—apart from the missionaries’ extension of their treaty protections to the converts—was the development of the Miao writing system. The migratory Miao people historically had no written language, which contributed to their state of marginalization and exploitation. The Miao legend told of the calamitous loss of their books to the Yangtze River in ancient times when their ancestors, driven out of the North China plains by the Yellow Emperor, crossed the great river.Footnote 7 Within months of the coming of the Ahmao in 1904, Pollard, working with local Christians, began developing the first Miao script. Based in part on the Pitman shorthand, it derived linguistic symbols from Miao batik and embroidery designs, and became known as the Pollard script.Footnote 8 The invention of the script led to the translation of the Bible and fulfilled the Miao prophecy of the recovery of the book: Pollard had retrieved the ancient Miao books that the great river had swept away.Footnote 9 He must be the savior-king. Many Ahmao Christians “persisted in addressing the missionary himself as God,” Pollard noted, referring to himself in third person.Footnote 10

The second story began at almost exactly the same time, some 500 kilometers south of Zhaotong, in the Burmese town of Kengtung. American Baptist missionary William Marcus Young had arrived in Kengtung, capital of a small Shan state, in 1901 and had seen “few if any results for his enthusiastic and persistent labor,”Footnote 11 preaching in the bazaar in that Buddhist stronghold with more than forty monasteries filled with placid monks.Footnote 12 But in 1903, he was surprised by a rapturous response from a hill people outside Kengtung called the Lahu, known to the missionaries as the “Muhso,” whose ancestors, the Qiang, had migrated there from the edge of the Tibetan plateau, more than a thousand precipitous kilometers to the north.Footnote 13 Most of the Lahu inhabited the rugged mountains on the Chinese side of the border about 100 kilometers north of Kengtung.

It was just weeks after a Lahu uprising across the Chinese border was put down and its leaders fled into Burma. Some 30,000 had joined the uprising, the latest of more than twenty Lahu rebellions since the eighteenth century.Footnote 14 The Lahu who came to Young recalled prophetic dreams that had gripped the “entire tribe” following the death of their spiritual leader called A Sha Fu Cu a few years earlier. “They dreamed that the true God was coming soon” to cast into hell those who were given to drinking, gambling, and opium. “Many who have heard the preaching of the Gospel regard it as the fulfilment of their dreams,” Young reported.Footnote 15 A Sha Fu Cu allegedly had also foretold that their promised savior would be a white foreigner riding a white horse.Footnote 16 “Burn the beeswax candles and joss-sticks, that the day might soon come when the Lahu people will receive their enlightenment from God,” the Lahu holy man reportedly said in his death bed.Footnote 17 Anthropologist Anthony Walker explains that in Lahu, whiteness connotes purity and can be applied to “any charismatic religious leader of whatever race or ethnicity.”Footnote 18

Hundreds came to be baptized in 1904. “Muhso leaders, or prophets, came to us saying they had been searching for the true God for years,” Young wrote in his annual report to the Baptist Foreign Mission Society. The Christian teachings he was expounding did not sound foreign. The Lahu tradition had also spoken of the creation, the flood, and the coming of a savior. “They also have traditions concerning the lost book which they say the foreigner will bring to them .. . . When the leaders decided that this was the fulfilment [of their tradition], the people everywhere were ready to receive the gospel at once.”Footnote 19 In the next two years, thousands more descended on Kengtung for baptism.Footnote 20 A joint commission of Presbyterian and Baptist missionaries in the area reported that, to many Lahu, “Mr. Young was Jesus and [they] referred to him by that name.”Footnote 21

As for “the lost book”—the Lahu had had no writing system for their Tibeto-Burman language—the prophecy of its recovery began to be fulfilled in 1906, when Young's fellow Baptist missionary H. H. Tilbe arrived in Kengtung and, within nine months, devised the first Lahu writing system, which was used to produce Bible verses, hymns, and a catechism.Footnote 22 In 1907, Young made his first evangelistic trip into China, where he and a colleague baptized more than 1,500 Lahu and Wa people. In 1920, the Baptists would open their first mission in the mountain village of Banna (Nuofu) in the then border county of Lancang, as the center of the Lahu Christian movement shifted to China.Footnote 23 In less than two decades, membership of the Lahu church in Lancang would grow to more than 30,000.Footnote 24

As William Young began his work among the Lahu, he was also fulfilling the oracles of another minority group in the region—the Wa, who were widely feared for their hunting of heads to be offered to the spirits for good harvest.Footnote 25 An Astroasiatic people of the Mon-Khmer language family, whose hamlets are often found at 5,000 feet or more above sea level, the Wa had moved up from the south in pre-historic times and settled in the Awa Mountain area straddling the Chinese-Burmese border. Chinese dynastic records dating back to the Tang period (618–907) mentioned that the Wa lived in the deep mountains, used arrows tipped with poison for hunting, and were indifferent to new technology or material comforts of the valley civilization, such as shoes or horse saddles.Footnote 26 The Wa had come under Lahu influence in the nineteenth century and had joined them in the rebellion of 1903.Footnote 27 Their prophecy came from a religious leader known as Pu Kyan Long, who had led a reform movement to abandon headhunting. His followers were known as the “gaixin Wa,” or “Wa of the Changed Hearts.”Footnote 28 He was near the end of his life when he learned of the “White Book” and the “White Law” of God brought by William Young. “The time has now come . . . a teacher of the religion of God has arrived,” he allegedly told his disciples.Footnote 29 In 1904, Young reported that, among the Wa, thousands were “anxious for us to bring them the gospel . . . As a token of their sincerity they sent a small pony down as a present.”Footnote 30 It was a white pony.Footnote 31

As we shall find out, in a parallel to the Lahu story, mass conversions also broke out among the Wa after their encounter with William Young. By the 1930s, the second generation of the Young family missionaries had translated the New Testament and many hymns into Wa.Footnote 32 By 1956, despite open hostility from the new Communist government, Christians in the Cangyuan Wa Autonomous County near the Burmese border totaled some 15,000 and accounted for more than one third of the Wa population in that region.Footnote 33

The third case is the Christian movement among another hill people, the Lisu, also along China's border with Burma. James O. Fraser of the China Inland Mission arrived in the town of Tengyue (now Tengchong) in southwestern Yunnan in 1909 and, for five years, carried on evangelism among the local Han Chinese, who were generally hospitable but impervious to his exhortations.Footnote 34 In moments of despondency, Fraser had contemplated suicide.Footnote 35 Then the Lisu descended on him from the high mountains.

Like the Lahu, to whom they are linguistically related, the Lisu were descendants of the Qiang people who began migrating south from the Tibetan Plateau in the early fourth century BCE under pressure from an aggressive Qin state.Footnote 36 They shared the Lahu story of the Great Flood that inundated the earth. Only a brother and a sister who hid in a floating gourd survived the deluge. Helped by signs from Heaven, the two overcame incest taboos and married each other, thereby becoming progenitors of humanity—peoples of the gourd.Footnote 37 The Lisu and the Lahu became distinct ethnic groups by the ninth century.Footnote 38

Most Lisu settled in scattered hamlets on precipitous slopes along the upper Salween River 5,000 feet or more above sea level.Footnote 39 They clung to a subsistence existence of slash-and-burn agriculture on narrow red-soil plots wrested from rocks and pristine forests, living as serfs and guardsmen of headmen from the powerful Naxi ethnic group. Theirs was a precarious ecosystem of torrential monsoon rains, landslides, and earthquakes, as well as typhoid, malaria, and the like. For sicknesses and other misfortunes, the shamans would order livestock to be killed off and offered as sacrifice to the spirits.Footnote 40 It was an infallible, magic wand of poverty.

The Lisu's hardships were compounded by the storied loss of their book, which earned them the scorn of the Han Chinese as a people without writing. They remembered a distant past when the Mother-God gave words to the forefather of the Lisu, which he wrote down on a piece of deerskin and laid out in the sun to dry. A careless lad, he became occupied with other things while a dog came and ate up the deerskin. But the ancestors prophesied a time when a white Lisu king would come from a far country, and “he will bring books in the Lisu language.”Footnote 41

Fraser stepped into that legend. With the help of a young Karen evangelist from Burma, he developed a Romanized Lisu script in 1914, using the English alphabet and additional symbols made from inverted letters, and elements of Burmese orthographic practice.Footnote 42 Before long, he had Mark's gospel and a catechism produced in Lisu and printed by the American Baptist Mission Press in Rangoon.Footnote 43 A new convert showed a photograph of Fraser in Lisu dress to the villagers: “Look, here's your king at last! He's white and he's making books.”Footnote 44 Lisu evangelists also made much of the similarity between the sound of “Jesu” and that of “Lisu.” “Jesu of the Lisu—was He not their Coming One.”Footnote 45 Fraser's fellow CIM missionary Isobel Kuhn noted that his “white-man appearance so monopolized interest that no one remembers his message.”Footnote 46 Where Fraser went, almost the whole village would come, “crowding the room to suffocation round the fire,” he reported. “The work was practically begun and has been almost wholly carried on by the Lisu themselves.”Footnote 47

What these cases had in common was that, in each of them, there was an expectant ethnic group whose enchanted response took the missionary by surprise. His words suddenly gained resonance, and the foreign religion became the foretold means of deliverance for the disheartened people, transforming them into an exultant community of the saved. It was the moment when ancient oracles were being fulfilled.

As I will attempt to show, the peripheral peoples under discussion who inhabit China's ethnic frontiers in Southeast Asia were pursuing their own destinies in their modern encounter with Christianity, guided by prophecies of redemption handed down from the past. Those prophecies had arisen in the course of their resistance against the Han-dominated Confucian empire, which pursued its grandeur at the expense of the upland minorities. Time and again, those oracles had ignited revolutionary chiliasm, each time extinguished in a blood bath. The hill peoples’ embrace of Christianity successfully channeled their desperate prophecies—“what mysticism had poured, while hot” into their soulsFootnote 48—toward a reformist messianism, which crystalized into palpable transformations of their society. Ostensibly a break with many of the ethnic traditions, Christian conversion ironically also fortified indigenous identities and generated fresh resiliency for their own material and cultural survival.

II. Waiting for Deliverance on the Margins of the Chinese Empire

Historically, the hill peoples on the ethnic frontiers lived in the shadow of the Han Chinese empire, which had no need for prophecies. It had imperial rituals of sacrifice to Heaven, the myths of the sage-kings of the past, and claims of the Mandate of Heaven—or, in modern times, sanitized party history and Marxist theories of immutable laws of historical progress—to legitimize the political order. What came close to prophecy was the “Li Yun” (Conveyance of Rituals) chapter in Li Ji, or The Book of Rites, attributed to Confucius but written hundreds of years later during the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE). It painted a utopian, egalitarian society of the “Great Harmony” (datong)—set in the past, not in the future—in which “the world was shared by all,” and the widowed, orphaned, the diseased, and the disabled were cared for.Footnote 49 It was only during the unprecedented civilizational crisis toward the end of the Qing dynasty that Kang Youwei sought to turn the “Great Harmony” into a vision of the Chinese future. Even that did not amount to a prophecy. As Herman Gunkel pointed out, prophetic utterances typically proceeded from the prophet's mysterious experience of oneness with God and with divine purposes in history, and the most ancient form of prophecy was “the oracle against a foreign and hostile land.”Footnote 50

Ethnic minorities on the margins of the Chinese empire had a long tradition of prophetic utterances of deliverance from hostile forces—the intrusion of an ethnocentric and high-handed imperial state into their land, and the often crushing burden of taxation and servitude that accompanied it. However, textual accounts of their salvationist oracles are spotty: they typically had no writing system to maintain records, and no equivalents of the Daoist oracle Scripture on Great Peace (Taiping jing), for instance, which inspired the Yellow Turban rebellion of the second century CE. Dynastic records, produced by Confucian elites trained in the imperial examination system, often contained extensive details on the material life and rebellions in the frontier regions but spilled little ink on the imaginary world the hill peoples inhabited. The result was the scarcity of official references to prophetic utterances. Yet the persistent recurrence of the latter, as well as their centrality in minority peoples’ uprisings, can still be glimpsed from available historical sources.

Starting from the Western Han dynasty, the imperial policy toward the peripheral peoples—the yidi, or “barbarians”—was one of jimi, or “bridle and tether.” Its goal was indirect control through ethnic leaders, which was deemed sufficient to pacify them and forestall rebellions.Footnote 51 In subsequent dynasties, notably the Tang, jimi continued as the practical means of asserting imperial domination over far-flung regions, while the state sought their increasing integration into the Chinese empire. The Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) began the practice of formally installing hereditary ethnic headmen called tusi in minority areas, complete with enfeoffment letters and official seals, to manage local affairs under detailed mandates for the fulfillment of tax and tribute obligations.Footnote 52 After the overthrow of the Mongols, the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) began military colonization (juntun) of the southwestern region, which also opened it to a rush of migrants from other parts of China, with over a million Han people settling in Yunnan in early Ming, assimilating minority members or forcing them to retreat into the mountains.Footnote 53 In 1413, the imperial court moved to abolish the tusi in some areas in Guizhou and replaced them with directly appointed officials in what became known as gaitu guiliu.

The intrusion of the Chinese state also intensified in terms of attempted cultural assimilation. The instructions that the founding emperor of Ming gave to the tribute-bearing chieftains of the “southern barbarians” was to send all their sons to imperial academies “to be taught the Way of the Ruler and the Minister” as well as proper Confucian codes of conduct so that they could “transform their local customs to become Chinese.”Footnote 54 In many cases, the conversion of tusi-administered areas into counties and prefectures led to increased tax burden, seizure of valley farmland by the Han migrants, and souring ethnic relations.Footnote 55

The result was predictable: between 1416 and 1426, more than eighty rebellions broke out in minority areas in Guizhou in “disobedience to taxation.”Footnote 56 The policy of gaitu guiliu vastly expanded after 1726 when Ortai, governor-general of Yunnan and Guizhou, memorialized the Qing court to dispatch the imperial army to remove the tusi in the mountainous region, tame its inhabitants, seize their land, and secure waterways to extract natural resources and promote trade.Footnote 57 It steered the Chinese state firmly into a collision course with minority peoples, setting off repeated uprisings, which often featured glorious prophecies of deliverance.

III. The Miao King

Among ethnic minorities of Southwestern China, the Miao enjoys a dubious prominence in imperial records of insurrection. (The term “Miao” has largely been avoided in scholarly works in the English language since the 1970s, but it is the standard term found in Chinese sources and will be retained here primarily for that reason.Footnote 58) Qing scholar Yan Ruyi devoted twenty-two volumes to a compendium of information on the Miao entitled Reference for Defense against the Miao, completed in 1799 and printed in 1820.Footnote 59 An important reason was that the Miao, with a population of perhaps some two million, was the largest ethnic minority—and probably the most restive—in the southwest.Footnote 60

The Miao story is generally traced back to Chiyou, the reputed Miao ancestor and leader of a powerful tribal alliance, who allegedly lost the Battle of Zhuolu (southwest of Beijing) to the Yellow Emperor around 3,000 BCE.Footnote 61 Driven out of the North China plain, the Miao embarked on their southward migration across the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers, which eventually took them into some of the most treacherous terrains of Southwestern China and beyond.Footnote 62

The precariousness of the Miao existence took on new urgency following the implementation of gaitu guiliu in the early fifteenth century, whereby the tusi, the local headmen, were replaced with Han Chinese magistrates. The more than eighty ethnic uprisings in Guizhou between 1416 and 1426 broke out in a predominantly Miao area.Footnote 63 For them, subjugation and exploitation by the Chinese state repeatedly sparked fiery visions of liberation under a messianic “Miao King” who would free them from all taxes.Footnote 64 Word of the appearance of the “Miao King”—often proclaimed in a state of trance—almost always played a critical role in Miao uprisings in history.Footnote 65 During the Ming period, some of the Miao rebellions featured the worship of Maitreya, the Buddha of the future, a sign of White Lotus influence.Footnote 66 In 1735, tens of thousands of Miao villagers in southeastern Guizhou, hearing that “the Miao King has come,” rose up against ruinous taxes, corvée labor, and land grab by the Han Chinese. In the end, “no fewer than 300,000” Miao were killed or died from starvation under siege.Footnote 67 In 1740, another uprising broke out in the Hunan-Guangxi border region. The rebels claimed that Li Tianbao, a Miao rebel leader captured and executed in the mid-fifteenth century, had returned and that there would be “great peace all under heaven.”Footnote 68 Beliefs in the return of a messianic Miao king surfaced again in the 1795 and 1855–1872 rebellions. The latter mobilized more than a million people across five provinces in the southwest in an eighteen-year struggle to break free of the Han rule.Footnote 69

After each failed uprising, the Miao were further dispersed. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a series of mass migrations southward took many of them out of China into Vietnam and Burma in particular.Footnote 70 It was in that state of prolonged, quiet desperation that the expectant Ahmao encountered the missionaries. For them, ancient prophecies were finally being fulfilled. As Pollard reported, “the rumour went abroad that Jesus was coming again very soon. . . . Some of the old wizards, and some of the singing women tried the role of prophet, and several dates were announced for the appearance of Christ.. . . They had known the bitterness and degradation of heathenism for so long, that we cannot wonder at their hopes for a short cut to the Millennium, when all wrongs would be righted and everybody have a chance.”Footnote 71 Those “female prophets” arose among the new converts as early as 1907 and gathered large followings with their promise of “boundless bliss” when the Savior returns.Footnote 72

IV. The Savior for the Lahu and the Wa

The Lahu who came to the Baptist mission in Kengtung in 1904 were apparently unaware of the parallel people movement around Pollard 500 kilometers north. They had been on their own grievous journey, begun more than two millennia before, down the eastern edges of the Tibetan plateau. By the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), they had left their grassy homeland and moved into the central part of Yunnan.Footnote 73 During the Han dynasty, Yunnan became a prefecture, but the policy of the Wu Emperor (156–87 BCE) toward minority peoples was to “govern in accordance with their own customs; collect no taxes.”Footnote 74 That tactful restraint with indirect rule continued under the Tang dynasty. Eventually, the local Han people began to demand taxes, and conflicts erupted. According to the Lahu oral tradition, their fierce warriors lost their strongholds in the valley after Lahu women were tricked into trading the staghorn triggers in the men's crossbows for the bamboo mouth harps brought by the Han traders.Footnote 75

The Lahu retreat into the mountains was further precipitated by the Mongol conquest of the 1250s, which drove them south from the Midu area in central Yunnan into Simao, Mojiang, and Lincang, where they came under the dominance of the ethnic Dai nobility, serving as serfs or tenant farmers.Footnote 76 At between 3,000 and 6,500 feet above sea level, they lived on hunting, gathering, and slash-and-burn, shifting cultivation, growing buckwheat, yam, and corn where they could.Footnote 77 Yet, their bards sang songs of their lost homeland, where a great salt lake (Qinghai Lake) was the bathing pond for the sun and the moon. They sang of a future cosmic renewal, when the “White Child” of G'ui sha, the supreme Lahu deity and the creator of heaven and earth, would come, granaries and livestock pens would be filled, hunger would forever disappear, and youth would be restored. There would be moral regeneration as well, and justice would finally prevail.Footnote 78

Gaitu guiliu, the imposition of direct imperial administration, reached southwestern Yunnan in 1725. Prefectural officials as well as a garrison were posted, and land tax was assessed.Footnote 79 The imperial state also imposed a tea monopoly, which halved its procurement price and the income of local growers. Many Lahu as well as Dai households were reduced to “selling their children to pay for the grain tax.” Within three years, a Lahu uprising broke out and hundreds perished when it was crushed. Another wave of Lahu migration followed. Some fled across the border into Southeast Asia; others retreated deeper into the mountains to dwell in caves and live by hunting, “free from both taxes and corvée labor.”Footnote 80

The next two centuries witnessed some twenty unsuccessful Lahu uprisings against official exploitation and oppression.Footnote 81 The upheavals opened the Lahu to the influence of Buddhist salvationism, first introduced during the 1730s —in its Theravada form—by a Dai (known in Burma as the Shan) monk, who was believed to be able to “dissolve hardships.”Footnote 82 The more lasting Buddhist influence—of the Mahayana tradition—was brought to the Lahu in the late eighteenth century by Yang Deyuan, a Han Chinese monk of anti-Qing persuasions and a healer versed in Chinese medicine. Yang preached a messianic message of deliverance from this-worldly suffering, and successfully laid the groundwork for a theocracy that melded Mahayana Buddhism with the indigenous Lahu chieftain system. Revered as the Buddha-G'ui sha—a Buddhist reincarnation of G'ui shaFootnote 83—he promised to return to this world after death, which would “herald a utopia for the Lahu people.”Footnote 84

After Yang died, the Buddhist theocracy continued under a disciple, the monk Tongjin, who gave his blessings to the 1799 Lahu rebellion, expanding its ranks to over 50,000. Even though the revolt was put down and Tongjin was eventually put to death in 1812 by slicing—which resulted in the destruction of the theocracy—glorious visions of a future deliverance persisted, as did more armed rebellions.Footnote 85 Meanwhile, A Sha Fu Cu had emerged in the late nineteenth century as the new spiritual leader, a “living Buddha.” In the Lahu oral tradition, A Sha Fu Cu constantly wept “because of the sufferings of the common people,” and promised to protect them for all eternity.Footnote 86 His campaign for moral reform and Buddhist piety reached beyond the Lahu region of west-central Lancang deep into the Wa settlements in Ximeng near the Burmese border.Footnote 87

Among the Wa, Mahayana Buddhist influence, which began in the 1850s,Footnote 88 continued under A Sha Fu Cu and, after him, the Wa prophet Pu Kyan Long, who worked to dissuade the Wa from headhunting.Footnote 89 Like A Sha Fu Cu, he had millenarian visions of God sending the “White Book” and “White Law” to the Wa people, and in 1904 dispatched emissaries to William Young in Kengtung, bearing the gift of a white pony.Footnote 90 Other Lahu prophets also arose during this period, making “extravagant and fantastic claims of power and [defying] government authority.” Those claims were often “coupled with promises of a new order,” noted Harold Young, son of William Young. “They sing the traditional songs . . . [and perform] some mysterious things such as blowing on water and pouring it on the sick to develop a cure. . . or by dancing on the limb of a high tree with both hands on a musical [gourd] pipe.” Proclaiming that a new era has dawned, “they tell people that they no longer need to obey mere human rulers.”Footnote 91 Those prophecies of a final earthly salvation “prepared the people in a most amazing way for the coming of the Christian Gospel,” Harold Young wrote.Footnote 92

V. The Coming of the Lisu King

Like the Lahu, the Lisu forebears were driven from the valley into the deep mountains as the imperial state extended its rule into the western frontiers, a process accelerated by the Mongol conquest. This continued during the Ming dynasty, with the dispatch of imperial garrison and the influx of Han laborers and merchants into Yunnan.Footnote 93 A fifteenth-century local chronicle reported that the Lisu “dwell in the mountain forests, maintain no agriculture, and often go hunting with bows and poisoned arrows. . . . They pay their annual dues to the officials [local headmen] only with game hides.”Footnote 94 Sixteenth-century records from the Lijiang prefecture show that, by then, many Lisu had become serfs and guardsmen of Naxi headmen, serving as their foot soldier when conflicts erupted with the Tibetans.Footnote 95

With the introduction of gaitu guiliu in western Yunnan in the early eighteenth century, imperial officialdom was superimposed on top of the administration of local headmen, who continued to demand corvée labor and to extract annual dues of cash, goldthread roots (used in Chinese medicine), game hides, and livestock from the Lisu.Footnote 96 Repeated Lisu uprisings followed, three of them—in 1801, 1821, and 1894, respectively—in the Lijiang area. In each case, millenarian beliefs, at times inspired by a “god king,” played a central role.Footnote 97 The calamitous end to the uprisings uprooted Lisu communities, sending them fleeing “in the direction of the setting sun” into the upper Salween River valley, which eventually became the Lisu heartland, or trekking on further west over the Gaoligong Mountains into Burma. Others followed the Salween and the Lancang Rivers and migrated south into the Canyuan and Menglian areas of southwestern Yunnan and beyond, and eventually found themselves in Thailand and Laos.Footnote 98

Despite repeated suppressions, anticipations of the coming of the Lisu King endured. In 1902, some 1,500 Flowery Lisu in the town of Diantan, Tengyue, near the Burmese border, followed a “Lisu King” with bows and poisoned arrows in a bid to take back their lost land. They held out for three months.Footnote 99 To those from the Lisu mountain hamlets, who encountered James O. Fraser in Tengyue around 1910, Christian teachings rekindled the flame of ancient oracles. “One thing especially appealed to them,” Fraser reported in 1913. “Whilst there I told them of the second coming of our Lord and the blessedness of His millennial reign, bringing peace, prosperity, and happiness to all mankind. This is splendid!—they think. They will get fine crops of buckwheat when that time comes. . . . It seemed as if God has been preparing their hearts.”Footnote 100 Indeed, the Lisu remembered what their forefathers had promised: “some day our Lisu king would come.” He would be white, and he would “bring us Lisu books.”Footnote 101 Fraser's coming had long been foretold.

VI. Transforming Prophecies: The Deliverance of the Enslaved

Surprising even the most starry-eyed of the missionaries, the Ahmao, the Lahu, the Wa, and the Lisu saw the coming of Christianity as the fulfillment of their age-old prophecies of deliverance. Missionaries’ treaty rights, which they often claimed for their converts as well, titled the balance of power away from Chinese magistrates and powerful local headmen who had long lorded it over the peripheral peoples. While foreign missionaries and local church leaders were occasionally targeted for violence when they intervened on behalf of the oppressed, they appeared nonetheless as Moses-like figures leading the people in an exodus from inhuman treatments, and in many cases from their own onerous traditions as well. In their search for earthly redemption, many minority communities made the fateful choice of surrendering their poetry of messianic uprisings for the prose of Christian reforms.

In the border regions of Yunnan and Guizhou, Samuel Pollard emerged as a Miao deliverer-king. “It is a shame that [the Miao] should be so oppressed and persecuted. They are as slaves, like the Israelites in Egypt under Pharaoh,” he observed in 1904.Footnote 102 He paid visits to the castles of Nosu tumu, landlords and masters of Ahmao serfs and tenant farmers, over cases of mistreatments, and bargained for lowered rent, or to convert rent payments—traditionally collected in distilled spirits or opium—into cash;Footnote 103 he also secured from local authorities a proclamation of official protection of Westerners—which he was allowed to edit, changing “Westerners” into “Christians.”Footnote 104 Those who joined the church were no longer “so easily oppressed and they will not so readily accept corvée,” Pollard wrote in a diary in 1904.Footnote 105 One Nosu headman who converted “released all his slaves and burnt the papers that bound them to him.”Footnote 106 In 1905, Pollard obtained from An Rongzhi—a Nosu tumu and lord of sixty Ahmao villages—a gift of ten acres of land at Shimenkan, the Stone Gateway, which became the cradle of Ahmao Christianity.Footnote 107

As Christian communities began to form, they renewed the social cohesion that had been weakened after failed uprisings and subsequent dispersion. In Lancang, a local official in a Lahu area observed in the 1930s that Christian churches were replacing former Buddhist temples as new centers of authority.Footnote 108 “How much better off the Miao are now than they previously were,” a Nosu landlord in Western Guizhou pointed out. “No one dare molest them now as they formerly did; they are able to keep their cattle and horses; the people of the neighbourhood think twice before they interfere with the Miao now they have joined the Church.”Footnote 109 In the Lisu village of Liwudi in the upper Salween River valley, a traveling mapa (evangelist) faced down a Han debt collector who had threatened violence against the villagers, and the latter concluded that “the Han Chinese dare not offend the mapa. When we follow the mapa in the new faith, the Han Chinese will not dare to bully us again.”Footnote 110

To the missionaries, a peculiar form of oppression that the minority upland peoples endured was internal. As James O. Fraser wrote in 1913, the Lisu “are one and all held in bondage through the fear of evil spirits. Even though in abject poverty, they will offer pigs, fowls and other things to appease these spirits,” so that they would not “bite,” or cause sickness.Footnote 111 He reported that in the village of Tancha, Tengyue, “demon-priests were forced to propitiate ‘the great spirit’ from time to time by getting volunteers to walk up a ladder of sharpened sword blades,” which they did “naked, and in a state of trance.” They explained that “they wish they knew how to get rid of the burden; but they must do it, whether they want to or not.” Footnote 112

Such a debilitating fear of evil spirits was in fact widespread among the hill peoples on China's ethnic frontiers in Southeast Asia, where the threat of malaria, typhoid, and dysentery was constant, along with other deadly diseases. It was a distant land from Mark Twain's dreamy Hawai'i, where a pre-Christian indigenous population went “fishing for pastime and lolling in the shade through eternal Summer, and eating of the bounty that nobody labored to provide but Nature,” blissfully ignorant of the Devil and hellfire.Footnote 113 As Yan Ruyi pointed out in his 1820 compendium on the Miao, they “would attribute any sickness to the work of the evil spirits and would ask the shaman to offer prayers, brewing wine and killing livestock” as sacrifice, which would be mixed with cat's blood. “All the Miao fear the evil spirits more than they do the laws of the land,” he wrote.Footnote 114 Sacrifices of this kind cost up to 100 taels of silver each time. “Those who are too poor to afford it would sell their properties or pawn their clothes.”Footnote 115

Appeasement of the evil spirits through lavish animal sacrifice unsurprisingly exacerbated poverty and starvation.Footnote 116 A Ximeng Wa settlement of 407 households and 1,487 inhabitants scattered in seven hamlets—which experienced chronic food shortages—“slaughtered 874 cows for major religious purposes” in a span of two years, an average of two cows per household. If converted into grain, one such offering could have fed every mouth in the settlement for seventy-four days, according to an official investigation.Footnote 117

For the Wa, the practice of headhunting was likewise rooted in fear. Living in the cold, wild Awa mountains on the Burmese border, their crops failed with frightening frequency and required emphatic appeals to the spirits. Or the seeds would not germinate and starvation would follow.Footnote 118 During the months-long headhunting season, which began in March, heads were procured to be offered as sacrifice. The Wa believed that “if at least one is not procured annually for each village, disaster is expected to follow.” A head with long hairs was a prized trophy—“hairs of head long, ears of corn likewise.”Footnote 119 The hunted head was brought back to the village and “hung up on a high bamboo frame, while directly below . . . a large pile of loose earth is placed. Then the drippings from the head are carefully mixed with the loose earth, and each family in the village or group of villages is given a handful of this earth to scatter over his fields to ensure a good crop.”Footnote 120 The ritual recalls human sacrifice made by the Pawnees that James George Frazer documented in The Golden Bough, in which blood was squeezed from the dismembered flesh upon the newly sown grains of corn to ensure plentiful crops.Footnote 121 The Wa headhunting often provoked self-perpetuating cycles of revenge among different villages, which could last for more than 200 years.Footnote 122 It is not surprising that the Wa prophet Pu Kyan Long at the turn of the twentieth century had sought to make “gaixin Wa,” the Wa of changed hearts, and envisioned a future when the violent chaos of the Wa life would end.

As the Christian movement spread among minority communities, animal sacrifice to the spirits gave way to modern medicine; churches often doubled as local health clinics, and vaccinations for the children, the application of iodine to prevent infections, along with medicine for common ailments such as malaria and dysentery replaced the offering of oxen, pigs, and grains.Footnote 123 In 1919, the Ahmao church in Shimenkan added its first leprosy asylum to the mission dispensary.Footnote 124 Better nutrition was achieved when missionaries introduced new vegetables—peas, beans, cauliflower, cabbage, spinach, onion, gourd, tomatoes, and the like—to supplement the monotonous diet of corn and buckwheat. Christian communities also started the cultivation of new fruits such as grapes, pineapples, plums, and figs, as well as juicier varieties of oranges (sometimes with cuttings sent from Florida and California).Footnote 125

In all known minority Protestant communities, the church also waged war on alcohol, opium, and unregulated sex. Among the Lisu, the dispiriting cycle of care-free drinking and hunger had been documented at least since the 1700s, when they were known to “use much of their harvest [of buckwheat and corn] to brew liquor. They drink on for days and nights, until it runs out after a few days. When the grains are all gone, they take up cross-bows and poisoned arrows and go hunting.”Footnote 126 In the upper Salween River valley, it was estimated that more than 12 percent of the area's meagre grain harvest in the early twentieth century was used for liquor, and many villages had to endure food shortages for four months out of each year.Footnote 127 In one Wa village of 214 households, 68,720 jin (75,600 pounds) of grains were used for making alcohol in the span of one year, an average of 75 pounds per person, the equivalent of more than two months of provisions.Footnote 128 The church's war on liquor as well as opium was swift and unforgiving. The Ahmao church banned whiskey from the very beginning.Footnote 129 The Lisu church modified the “Ten Commandments,” directing divine wrath against drinking, gambling, and opium-smoking along with brawling and traditional dancing and singing.Footnote 130

In the early days, missionaries were scandalized by the prevalence of haphazard sex among the hill peoples, such as the Miao su zhaifang, or “sleeping in the hamlet house,” which villages maintained to allow their young women to attract men from other clans, who would marry into the women's families.Footnote 131 The Miao were also known for their huachang, the “Feast of Flowers,” an annual festival featuring the “lusheng dance”—with fertility rhythms and dramatic reenactments of the Miao's historic migratory treks as well as sacrifices to the ancestral spirits.Footnote 132 Pollard called it “a tribal celebration of dancing, feasting, drunkenness and much immorality.”Footnote 133

The church's solution to the problem of questionable rituals of courtship was to either ban or Christianize them. In Shimenkan, Pollard inaugurated a Christian festival on the day of the “Feast of Flowers” to “compete with the heathen hua-chang.”Footnote 134 Across Lisu communities, hymn-singing competitions were held at church festivals to replace the flesh-tingling yodels, which young men and women used to keep up on mountain trails as they slipped through the shadows at dusk.Footnote 135

Reform of marriage customs also followed. Among the Ahmao, for instance, not only had traditional marriage tended to be fragile—destabilized by huachang, su zhaifang, and a laissez-faire practical philosophy of sexFootnote 136—weddings had always incurred an outsized financial burden, as the bride's family would demand cattle (or sheep or pigs) in payment. The poor, as Pollard found out, would “take a wife ‘on account’ and pay up the cow later when they have one.” In response, the Ahmao church made all Christian families sign an agreement to marry among themselves and to “give up the selling of daughters,” limiting gifts to a bride's parents to “one pair of fowls, one bag of oatmeal and one leg of meat.” Minimum age was set for marriage—eighteen for the bride and twenty for the bridegroom.Footnote 137 The church also waged war against inbreeding, which had been widespread among some hill peoples and was often correlated with mental retardation.Footnote 138

VII. The Return of the Books: The Vernacular Bible and the Renewal of Ethnic Identity

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the Christian movement, one that fulfilled the timeless prophecy shared by all the minority peoples under discussion, was the return of the “lost” book. Not only did the Miao and the Lisu inherit tales of the calamitous loss of their books, so did the Lahu, and many other ethnic minorities that peopled the austere Southeast Asian massif (the Zomia)—including the Jingpo (Kachin), the Karen, the Akha (Hani), and the Qiang.Footnote 139 In the Lahu story, the Great Progenitor long ago taught writing to the humans. He wrote the words on a piece of paper for the Han Chinese, and on the pattra palm leaves for the Dai. The Lahu ancestor received the writing on a rice cake. Each was told to take the writing back to his people. On his way home, the Lahu ancestor grew hungry and ate the cake, and their language was lost.Footnote 140 The absence of the written script reduced these peripheral groups to tying knots or carving wood for record-keeping and contracts.Footnote 141 Anthropologist Nicholas Tapp has argued that what brought the hill peoples to Christianity was “above all the desire for literacy.”Footnote 142 For them, the written word embodied both political and magical power.Footnote 143

In the emergence of the writing systems for the hill peoples, the initiative invariably started with pioneering missionaries eager to translate the Bible into indigenous tongues. The broader phenomenon of the vernacular translation of the Bible in modern mission fields can be traced back to the work of William Carey soon after he arrived in Calcutta in 1793.Footnote 144 In the early nineteenth century, Protestant missionary work among native Americans also involved the creation of written alphabets, which produced literary rates as high as 50 percent among some groups.Footnote 145 In every documented case in the China-Southeast Asia borderlands, the creation of the missionary script was made possible by the able and often eager assistance provided by local converts. Behind the CIM missionaries’ production of the Lisu writing system and of the Lisu Bible, for instance, was the linguistic gifts of both Karen and Lisu evangelists.Footnote 146 The same was true in the creation of the Romanized Lahu and Wa scripts and the making of their Bible.Footnote 147 Working among the Ahmao, Samuel Pollard drew extensively on local help in the design of what became known as the “Pollard script” (or the “old Miao script,” as the Ahmao call it).Footnote 148 Vernacular translations of the Bible, initially containing one or two of the gospels, began to appear in the late 1900s; the Ahmao New Testament was printed in 1917. By the 1930s, the Lisu, the Lahu, and the Wa New Testament had also been published.Footnote 149 Hymnals and primers printed in the new scripts during the same period joined the Bible as sacred texts that came to define the Christian communities.Footnote 150

In the long run, the creation of the vernacular script and the translation of the Bible transformed the hill peoples far beyond the missionary goal of Christianization. More than anything else, the vernacular Bible helped standardize and preserve the indigenous language, which had often been fractured into regional dialects in the process of migration and dispersion and diluted with loan words from the valley civilization. It gave its people a renewed sense of common identity, set against the civilizing, nation-building project of the Chinese state, which made various attempts to eliminate both their language and their traditional dress.Footnote 151 During the 1930s, a committee charged by the Nationalist government with the drafting of frontier policies in Guizhou was particularly alarmed by the potentials of the Pollard script to undermine the state's project of assimilation. “Whoever wishes to eradicate an ethnic group has to eradicate its language first,” its report noted. “Likewise, whoever wishes to preserve an ethnic group has to preserve its language.” It added that Pollard had “wantonly created the Miao script.” If allowed to spread, “then the scattered Miao people would unite with the help of the written script, and stand tall and apart in their own culture.”Footnote 152

In effect, the report intuited what Benedict Anderson would postulate half a century later—that “sacral cultures . . . were imaginable largely through the medium of a sacred language and written script.”Footnote 153 The missionary script, created in the service of Bible translation, helped the Miao and other hill peoples recover the sacredness of their own cultures. It was only natural that their shared communities, now bound by the printed scripts, would bear, to borrow Anderson's words, “none but the most fortuitous relationship to existing political boundaries.”Footnote 154 During the 1930s, in both Lahu and Wa areas, Han Chinese officials were dismayed that minority converts, by then already sporting the printed gospels, hymns, and Christian primers in their own scripts, “thought in their ignorance that, by joining the church, they could rid themselves of governance by our country, and often refused to pay their dues in grains and their taxes.”Footnote 155

The rhythm of congregational life of the Christians, never before maintained among the peripheral peoples, amplified the unifying effect of the new writing system and the vernacular Bible. Christian schools, usually attached to the churches or set up inside them, sprang up in mountain villages and became centers of communal life. Literacy and formal education—at times complete with modern sports such as soccer, track and field, archery, horseracing, and swimming pools, and supplemented with vocational training—transformed mountain villages. Churches also introduced improved crops, handicrafts, and new textile machinery, opened clinics, and in some areas started agricultural cooperatives and provided credit through savings and loans.Footnote 156

At the Stone Gateway, the church-run elementary school pioneered Ahmao-Han bilingual education during the 1910s.Footnote 157 During the Republican period (1912–1949), thousands of Ahmao students graduated from church schools; more than thirty obtained college degrees, and two received doctorates.Footnote 158 Later studies showed that the new vernacular scripts generated literacy on a massive scale. During a four-month period, the introduction of the Romanized script eliminated over 70 percent of illiteracy in a Hani population in Yunnan—another peripheral people the missionaries reached in the early twentieth century.Footnote 159 Among the Lahu, as Anthony Walker observes, the creation of the Romanized script and mass education enabled the emergence of a “religious and secular intelligentsia that would lead them into the modern world.”Footnote 160 Across the border region, educated Christians accounted for a disproportionately large percentage of the local elites,Footnote 161 part of a broader phenomenon throughout China at the beginning of the Republican era.Footnote 162

In Yunnan and Guizhou, churches in the minorities region grew at a pace unrivaled in any other part of China during the first half of the twentieth century. By the early 1950s, an estimated total of more than 100,000 were found in Ahmao (and some Nosu) churches, most of them in western Guizhou.Footnote 163 Within Yunnan province, Protestantism gained a total following of more than 120,000 among peripheral peoples less than a half century after Christian work began among them.Footnote 164

VIII. Reflections on Mass Conversions on China's Ethnic Frontiers in Southeast Asia

Through most of the modern period, millions of hill peoples in the border regions of Southeast Asia remained largely invisible—except to missionaries and anthropologists, in that order. James Scott argues in The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland South-East Asia (2009) that they were runaways from state-making projects in the valley and were “barbarians by design.” Their migration to the margins of empires, their swidden agriculture, religious heterodoxy, and even their “nonliterate, oral cultures”—their illiteracy—were political choices as they “resisted the salvation religions of lowland peoples.”Footnote 165 However, their Christian conversion reveals a less dramatic choice in the twentieth century, one that points to considerable historical continuity in their dreams of earthly deliverance.

Anthropologists have sometimes reproved missionary work among the upland peoples as a “civilizing project,” which took advantage of their susceptibility. “The peripheral peoples provided more fertile ground than the Han,” Stevan Harrell writes, “on which to sow the seeds of the Gospel and modern life.”Footnote 166 Missionaries themselves were in fact the first to discover this. James O. Fraser explained in 1934 that “these aboriginal races, in South-West China at least, have been the veins of ore from which most of our metal has been extracted.”Footnote 167 The missionary project of transformation was in competition with that of the central state, which, as Benedict Anderson points out, was ever fearful of “‘sub’-nationalisms within their borders—nationalisms which, naturally, dream of shedding this subness one happy day.”Footnote 168 But the Christian movement offered the hill peoples an opportunity to choose. In the long run, unlike the state's coercive project of assimilation and ideological transformation, the missionary work—despite its war on local shamanism, the inherited (and often inebriated) rhythms of life, and even on traditional songs and dances—ironically also helped preserve their identities. Christian beliefs often became fused with indigenous memories and dreams to become an “outright ethnic marker.”Footnote 169 Anthropologist Yoichi Nishimoto observes that, among the Lahu, conversion also reshaped their historical memory into a linear “Christian Lahu mythology” with a “leitmotif,” foretelling a future in which “the Lahu may be able to regain the Lahu country and a Lahu king.”Footnote 170

This was made possible especially with the invention of the missionary script. Linguist David Bradley points out that, while “a distressingly high proportion of the world's languages”—including those on China's ethnic frontiers—have been threatened with extinction, vernacular writing systems developed in Bible translation have introduced a new “resilience.” And even as much of the traditional oral literature—long in the custody of shamans and kept alive in indigenous rituals and dances—has been lost in the Christian movement, its distinctive genres often survived “within new Christian material.”Footnote 171

In that process of Christianization, the poetry of tribal life—a fearful, forlorn, and often desperate kind of poetry pulsating with hunger, desires, diseases, violence, and messianic proclamations—gave way to the prose of Protestant teachings and reforms, such as modern medicine, a ban on drinking and opium, and domestication of sex, as well as written scripts to make books, and schools in which children shed their illiteracy.

Western missions among the peripheral peoples were of course the “detonator”—to borrow Andrew Walls's metaphor—of the Christian movement in the border region.Footnote 172 However, initiatives undertaken by indigenous inquirers and converts from the very beginning—Ahmao, Lahu, Wa, and Lisu—are in clear evidence.Footnote 173 They were the ones seeking fulfillment of the prophecy of their forefathers, and they considered it providential that the missionaries burst upon the prophetic scene in the depth of their historical crisis, following the repeated, disastrous collapse of their millenarian movements.

Among Christianized hill peoples, embers of the messianic fire were never extinguished. Throughout the rest of the twentieth century, new flames of redemptive prophecy would be kindled time and again in moments of desperation.Footnote 174 In 1945, four decades into the Christian movement, another Lahu prophet arose in the China-Burma border region, claiming that he had been sent by G'sui sha to deliver the people. Another rebellion was in the making, amid the throes of revolution in China and the independence movement sweeping across British Burma. A missionary's report at the time leaves us with this image of the Lahu holy man for whom the business of prophecy remained unfinished: “He performed a very difficult Lahu folk dance up on a high limb of a tree while holding and blowing the Lahu gourd pipe [naw-] with both hands. He claimed he could move mountains.”Footnote 175

That was another ascent to the perilous height of prophetic poetry. For hundreds of years, or longer, the hill peoples on China's ethnic frontiers in Southeast Asia had repeatedly erupted into such poetry when life became unbearable. During the twentieth century, Christian conversion and reforms fulfilled the ancient prophecies for hundreds of thousands of them, transforming their precarious poetry into viable prose, but it has not removed their ability to burst again into poetry when time calls for it.

Acknowledgements

Several individuals have provided kind assistance since 2014 as I conducted research for this paper. They include Professor Liu Dingyin of the Yunnan Academy of Social Sciences, Ahmao linguist and historian Tao Shaohu, Lisu pastors Jesse (Feng Rongxin) and Yu Yongguang of Nujiang, Rev. Jiang Zhulin, Dr. Philip Young, missionary to the Lahu, Dr. Zhu Jili of the Yunnan Academy of Social Sciences, Ahmao scholar Pan Xuewen, and Luo Zhou, Chinese Studies Librarian of Duke University. Professor Yoichi Nishimoto read and commented on a draft of this paper. My gratitude goes to all of them.