In 2014, while sitting in a busy Starbucks in the Shanghai suburbs, a human resources director at an internet technology firm complained to the author: “It is hard to win lawsuits against workers. The courts mostly side with employees.”Footnote 1 Similarly, a manager at an electronics factory in Wuxi related how her firm had hired a lawyer to analyse the outcomes of local employment disputes and that the lawyer had found that enterprises were increasingly on the losing side. As a result, the manager explained, her company was “becoming more careful, trying not to give workers an excuse.”Footnote 2 But a labour lawyer interviewed in Shenzhen painted a sharply contrasting picture: “The state is standing together with capital.” Beginning in 2010 onwards, he said, “police started hassling workers” who went on strike in the city, and by 2014 “over 100 workers were detained by police and 1,000 were fired by their employers with the support of courts.”Footnote 3 The leader of a labour non-governmental organization (NGO) described the situation in yet more dramatic terms: “The government is rougher now than before. It used to be newsworthy if the police used dogs on workers. When I put up a picture of a police dog biting a worker, lots of people shared it. If you didn't show a picture, no one would believe you. Now, using … dogs is not unusual. People feel it is like when the Japanese invaded.”Footnote 4 Thus, according to one narrative, the Chinese state is going out of its way to accommodate workers, placing businesses on the defensive, while according to another narrative, labour is coming under violent assault.

This article argues that both accounts contain elements of truth. Worker resistance is driving the state towards both increased repression and increased responsiveness. Existing scholarship has tended to focus on one or the other of these government reactions or, in more synthetic accounts, to treat the two as substitutes for each other. Yet, coercion and concessions come as a package. Having repeatedly emphasized that the will of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is supreme, the government cannot credibly wash its hands of complaints and defer to the judicial system or other institutions. Authorities must throw themselves fully into any conflict that has the potential to spread, ensuring workers get a sympathetic hearing while at the same time coming down hard on organizers to prevent mobilization from escalating. The country's lack of a real labour movement only deepens this trend. Without large representative organizations that can aggregate and prioritize worker demands, the state has even less of a sense than it might have otherwise of what will work to restore order. The default, then, is to try everything.

The article documents this contradictory dynamic in broad, quantitative terms. Specifically, using an original dataset of strikes, protests and riots as well as government budgetary and judicial statistics from 2003 to 2012, I show that positive correlations exist at the provincial level between increased worker unrest on the one hand, and both spending on the paramilitary police (repression) and numbers of pro-worker and split decisions in mediation, arbitration and court cases (responsiveness) on the other. These correlations hold even when I control for economic development, worker demographics and the power of the official trade union and NGOs. However, I find some evidence of reverse causality at work with regard to responsiveness: more worker wins, in turn, seem to encourage unrest. Finally, looking forward, I briefly address changes in governance under President Xi Jinping 习近平, suggesting that although repression and responsiveness both continue to be deployed by authorities, the balance of the state's response seems to have shifted decisively towards the former. The article's conclusion explores the implications of these findings. It argues that by spurring increased repressive and responsive capacity – and in recent years, especially repressive capacity – grassroots contention may be further empowering China's authoritarian leviathan but in a manner that is unlikely to be sustainable over the long term.

Repression and Responsiveness

Repression and responsiveness are typically examined separately. With regard to repression, scholars have long argued that there is a “law of coercive responsiveness”: put simply, states deploy repression when faced with threats to the status quo.Footnote 5 But not all dissent is perceived as equally threatening. Certain groups and tactics are viewed as constituting a greater danger than others, and police have accordingly been found to react differently to different sorts of protests.Footnote 6 Cross-national studies have tended to assume that repression is the default for authoritarian regimes.Footnote 7 However, researchers have documented a wide range of reactions to popular mobilization in the authoritarian Chinese context, from “relational repression,” meaning the targeting of friends and families of activists,Footnote 8 to active facilitation of demonstrations, as during patriotic anti-Japanese or anti-American protests.Footnote 9 Scholars have also examined how the Chinese public security apparatus has evolved over time, growing in influence and sophistication.Footnote 10 An unintentional danger with this work is that readers may come away with an exaggerated perception of the state's ability to control contention.

Studies of responsiveness, meanwhile, have tended to focus on the success versus failure of social movements to bring about particular government policies. For the most part, this research has focused on liberal democracies.Footnote 11 But scholars are increasingly examining the various institutions that authoritarian regimes possess for co-opting critics through shows of responsiveness, from controlled elections to rubber stamp legislatures.Footnote 12 In China studies, attention has focused on how the National People's Congress, village elections, the petitioning system, courts and arbitration panels, and informal practices like “protest bargaining” can serve as pressure release valves and means of collecting opinions and resolving grievances.Footnote 13 This has given rise to a plethora of new phrases to describe the country's governance: “contentious authoritarianism,” “responsive authoritarianism,” “authoritarian deliberation” and “consultative Leninism,” to name just a few. Here, the danger is different: readers come away with an overly accommodating view of the state.Footnote 14

Some studies have, finally, attempted a synthesis of these two lines of analysis. However, they have generally approached repression and responsiveness, phrased in different ways, as substitutes. Thus, for Ronald Wintrobe, the options are cracking down versus buying off dissenters.Footnote 15 Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, meanwhile, argue that the choices available to autocrats facing upheaval are democratization, policy change or coercion.Footnote 16 Charles Tilly offers three alternatives again – facilitation, toleration and repression – but although he leaves open the possibility that all might occur simultaneously, he does not explore this possibility further.Footnote 17 Having established stark decision trees like these, researchers have then proceeded to examine how the decision to muzzle dissent can drive activism in a more violent direction or how concessions might encourage further protest and the eventual overthrow of a government, etc.Footnote 18 In China studies, scholars have argued that by rewarding activism that, while disruptive, stays within certain boundaries (“troublemaking”) and punishing activism that crosses those boundaries, Chinese authorities train protesters to limit themselves to an unspoken zone of “safe” claim-making and gather valuable information on popular grievances at the same time.Footnote 19 Yet, a government can also show concern for contentious claim makers and crack down on them simultaneously. It is this seemingly contradictory approach that I explore in this article, along with the possible long-term implications of the approach for China's political development.

Research on Chinese Labour Activism

Scholars increasingly view Chinese workers as empowered and bringing about change. This represents a switch from earlier research. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, studies portrayed labour as being under the spell of the state's new market ideology and divided by the state's reliance on foreign direct investment.Footnote 20 Divisions were found also between migrant workers in the south-east and state-owned enterprise (SOE) employees in the north-east and interior and, within the group of migrants, between different gendered native-place networks.Footnote 21 Workers’ claims, in turn, were seen as essentially defensive: the maintenance of a tattered “socialist social contract” (SOE workers), the implementation of the most minimal standards found in the country's labour laws (migrant workers), and the provision of the social support needed to simply survive (SOE workers again).Footnote 22 However, as labour shortages grew on the coast and strikes and protests mounted, scholars began to highlight the emergence of experienced strike leaders, innovative tactics associated with fledgling labour NGOs, and offensive claims for better wages (unconnected to legal minimums) and for shop floor representation.Footnote 23 This empowerment thesis has not been without its critics.Footnote 24 But research has nonetheless begun to shift from the causes of industrial contention (or the lack thereof) to its consequences. Scholars have argued, for example, that workplace unrest is responsible for various regional experiments, embarked upon by the party-controlled All-China Federation of Trade Unions (Zhonghua quanguo zonggonghui 中华全国总工会, hereafter ACFTU), including the provision of legal services to migrants, direct elections for enterprise-level union leaders and practices that approximate to collective bargaining.Footnote 25 It has also been posited that labour protests were a driving force behind the passage of China's 2008 Labour Contract Law and other protective workplace legislation of the past decade.Footnote 26 Finally, researchers have made compelling claims that China's expansions of social insurance and job skills training in the late 1990s and early 2000s were reactions to that era's massive wave of state-sector activism.Footnote 27 This article adds a quantitative approach to what has until now been a largely qualitative field. More importantly, it attempts to avoid adopting either an overly optimistic or pessimistic perspective and instead shows how worker mobilization is drawing a state reaction that includes both empowering and stifling elements in an uneasy blend.

Argument

The argument made here is that repeated instances of worker resistance generate both increased government repression and responsiveness. This dual reaction springs in part from precisely the sorts of institutions that have been at the centre of studies of authoritarian responsiveness. Countries like China continually emphasize that courts and labour arbitration panels must follow the ruling party's lead.Footnote 28 This is a source of vulnerability as well as a strength. As others have argued, quasi-independent bodies can serve as pressure release valves and co-opt potential regime opponents. But, as a result of their repeated demands for loyalty, authorities cannot credibly “pass the buck” for resolving disputes to those same organizations, and much of the force of grassroots conflict is inevitably absorbed straight into the body of the state. Consequently, officials must intervene directly in conflicts and give a win to people with grievances. And then another win. And then another. However, there is danger for authorities, as social movements scholars have noted, that an “opportunity spiral” will form in which resistance generates responsiveness that in turn encourages further resistance, without end.Footnote 29 So, the government must simultaneously signal through coercion that there is an outer limit to what it will tolerate. For example, a group of protesters will be given what they want, but protest ringleaders will be detained once the situation quietens down. Or a whole mass of people will be attacked, but concessions will quietly be made at some later point. The fact that a country like China can successfully prevent the formation of fully fledged social movements means that it does not have to negotiate with any representative organizations; it also means that there is no one to aggregate and prioritize demands. The government therefore has a particularly poor sense of what will suffice to restore order. This, in turn, only deepens the state's dual – repressive and responsive – approach. For workers, this amounts to two steps forward, one step back.

Methodology

Documenting this dynamic is not straightforward. The appropriate timeframe for any analysis is short, as it is unrealistic to assume that today's worker–state interactions are similar to those of the early reform era, let alone the Mao era. Disaggregating China into its subnational units makes identifying relationships easier because it allows us to increase the number of “observations.”Footnote 30 In this article, my chosen level of analysis is provinces (and directly administered cities and autonomous regions). There are two reasons for this choice. First, with China's “soft centralization” of the late 1990s, more power has become concentrated in provinces.Footnote 31 Second, and equally importantly, more government data are consistently available for provinces than for other units such as counties or prefectures. My selected time period, meanwhile, is the decade between 2003 and 2012, i.e. the full administration term of leaders Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 and Wen Jiabao 温家宝, to keep the elite politics as constant as possible. Finally, my method is time series analysis. Compared with case studies, this approach has obvious shortcomings: it deals with important factors in a rough manner; it ignores the intricate interplay of social forces in China's workplaces (or at best, tries to control it away); and it only yields information on average relationships between variables, flattening time and place even as it takes advantage of them, while failing to document the precise mechanisms connecting protest and policy. However, the approach has the advantage of providing a bird's eye view of how the country is changing, a perspective that can be fleshed out with further qualitative research. Some dynamics, I believe, only become clear when we squint. In the following section, I explain how I measure my principle variables and controls. I then continue to provide more details on my statistical models before describing my results.

Measuring Worker Resistance

Measuring worker resistance in China is difficult because the country does not release official strike statistics. In the place of such figures, I have assembled a geo-referenced dataset of 1,471 strikes, protests and riots by Chinese workers (all are described as “strikes” hereafter) between 2003 and 2012. The incidents are mostly drawn from a close reading of state media, foreign reporting, dissident websites, online bulletin boards and, to a lesser extent, social media. A research assistant has double-checked the completeness of the dataset using a fixed set of search terms and sites. The Hong Kong-based advocacy group China Labour Bulletin (CLB) runs a similar strike mapping project, drawing on the same sorts of materials but using more social media, as well as interviews with Chinese workers conducted by the group's leader, Han Dongfang 韩东方, on his Radio Free Asia programme.Footnote 32 Although CLB has documented an impressive number of incidents, its collection only covers the years 2011 to the present. I have checked my dataset against the CLB dataset for the two overlapping years, adding any incidents captured by the CLB that I missed. My data are furthermore publicly available online and visitors to my website can upload reports on conflicts.Footnote 33 I have received information on half a dozen incidents in this way.

Representativeness of the Dataset

Despite these efforts at completeness, my dataset likely only represents a small fraction of the total worker unrest occurring. For a period, the Chinese government sporadically released figures regarding the annual number of “mass incidents” it experienced. Such incidents increased from 9,000 in 1994 to 87,000 in 2005, the last year the figures were publicly reported (a leak put the number at 127,000 in 2008).Footnote 34 These government counts were not broken down by protest type, but scholars have estimated that roughly one-third related to employment disputes (the next biggest category was land disputes).Footnote 35 This would mean that tens of thousands of workplace conflicts occur each year in China, and a single incident in my dataset therefore stands in for hundreds of incidents not recorded. As a non-random sample, the dataset might, of course, be subject to several biases. Relatively open state media, livelier internet users and a greater proximity to foreign observers could lead some regions of China to generate a disproportionate number of reports. However, although the dataset's incidents are concentrated on the coast, it nonetheless captures conflicts across a remarkable swathe of the country. This can be seen in Figure 1, which is a screenshot of the map on my website, with reports grouped by region. There might also be biases across time in the reporting of unrest, owing to censorship or shifting news cycles. But the timing of the incidents in my collection is largely as one would expect, both within years and between years: more incidents every year in December, before Spring Festival, as migrant workers prepare to return home for the holidays and desperately try to recoup wage arrears, and fewer incidents during and immediately after Spring Festival; fewer before the 2008 financial crisis, then a spike during the crisis, followed by a steady climb from 2010 onwards. Moreover, incidents are correlated fairly tightly (0.61) temporally and spatially with formally adjudicated employment dispute numbers. Although institutional worker activism and extra-institutional worker activism clearly have their own dynamics, they frequently overlap in China, with protesters taking their cases to court and litigators using protests to bolster their position. Workers also frequently “use the street as a courtroom” by drawing judicial authorities into negotiations with management at the site of confrontations.Footnote 36 Figure 2 charts incident numbers from my dataset alongside adjudicated employment dispute numbers year to year. Note that both lines generally trend upwards. However, they diverge after the 2008 financial crisis, suggesting that legal and extra-legal routes have increasingly become substitutes rather than complements for each other, with extra-legal routes winning out. Put differently, it seems that workplace conflicts are sharpening, despite the government's best efforts. This echoes other reporting.Footnote 37 In sum, the dataset is not perfect, but until the government begins releasing its own strike statistics following international best practices in data collection, my collection is likely to be the most reliable one of its kind, at least for the time period it covers. It has geographic breadth and largely matches other counts of contention, and where it diverges from those counts, it does so in a convincing and revealing manner.

Figure 1: Worker Strikes, Protests and Riots across China, 2003–2012

Figure 2: Worker Strikes, Protests and Riots versus Formally Adjudicated Employment Disputes in China, 2003–2012

Measuring Repression

Repression is at least as difficult to document as resistance. Christian Davenport and Sheena Chestnut Greitens both argue convincingly that repression should be understood to include a wide range of actions including non-state violence, surveillance and even negative media portrayals of particular groups.Footnote 38 In the context of Chinese labour relations, these have all come into play at various points. Leading organizers have been physically attacked. For example, Huang Qingnan 黄庆南 was nearly killed in 2007, although his assailants seem to have been thugs hired by angry employers, not the government.Footnote 39 Activists are regularly invited to “drink tea” with the police.Footnote 40 Industrial zones are packed with security cameras.Footnote 41 And if we include negative media coverage, as Davenport posits we should, then state newspapers’ regular condemnations of workers for using “extreme” measures can also be seen as coercive, intimidating would-be protesters. However, a simple measure of repression and one that lends itself to consistent documentation is police spending. The China Statistical Yearbook reports annual outlays for public security by province.Footnote 42 Unfortunately, this includes an overly broad swathe of the budget, covering such items as “expenditure for public security agency, procuratorial agency and court of justice” (through 2006) and more vaguely “expenditure for public security” (2007 onwards).Footnote 43 A better measure is spending on the paramilitary People's Armed Police (PAP hereafter), in particular. This force was established in the 1980s but received new powers following the Tiananmen Square massacre.Footnote 44 Control of the PAP has shifted back and forth over time but currently lies with the CCP Central Committee and the Central Military Commission.Footnote 45 Regardless of who is in charge of the PAP, however, the force is more decidedly “political” than the general police, charged as it is with the quelling of rebellions, riots, organized crime and terrorism.Footnote 46 The central government reportedly dispatched extra PAP to Guangdong following a 2010 Honda strike, for example.Footnote 47 These police are not routinely called out to tamp down protests, and there are limits on local officials’ ability to deploy them (they were not actually used against the Honda workers).Footnote 48 But, their concentration in particular regions represents a strong show of state concern over those places – and a greater capacity for repression there, whether that capacity is used or not. Regrettably, data that separate out PAP spending by individual province are only available through the year 2009 (via the local fiscal statistical yearbooksFootnote 49), shortening our analysis. Figure 3 tracks total regional and central spending on the force from 2003 to 2012 (unlike provincial breakdowns, these aggregate figures are available up to the present). Note that both the central and regional lines are rising steadily. However, central spending received a bump around 2008–2009, when China hosted the Beijing Olympics and the government confronted uprisings in Tibet and Xinjiang. This fits with arguments that the country's repressive apparatus has become more centralized.Footnote 50 It also suggests that this process started earlier than usually thought, under Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao, not Xi Jinping. If PAP expenditures do not perfectly measure repression, they provide a believable and illuminating measure of state stability maintenance priorities.

Figure 3: Spending on the People's Armed Police (1 million yuan)

Measuring Responsiveness

State responsiveness can also take many forms. As I have noted, some of these forms, such as new labour laws, trade union reforms and extending social insurance, have been the subject of other academic studies. However, I focus here on the most direct, common way for authorities to meet workers halfway: via rulings in formally adjudicated employment disputes. The government's release of aggregate employment dispute figures has already been mentioned, but the data extend beyond these totals. Detailed provincial breakdowns of the number of disputes decided in a pro-worker, split or pro-business manner are also made public. Pro-worker decisions here mean rulings that are fully in favour of workers. Split decisions, which come closer to realizing the Communist Party's preference for harmonious “win-win” (shuangyin 双赢) solutions, refer to rulings that hand partial victories to employers and employees alike. In practice, splitting frequently entails compromising on workers’ rights – for example, awarding employees only a portion of the compensation they are legally owed for an occupational injury – but not compromising on companies’ prerogatives. Still, even such decisions are an improvement over rejecting labour's demands outright, which happens when the government is particularly concerned about retaining investment, such as immediately following the 2008 financial crisis in some places.Footnote 51 Figure 4 shows that while decisions of all types have risen – after all, the total number of disputes has risen – pro-worker and split decisions have far outstripped pro-business decisions. Interestingly, split decisions have also overtaken pro-worker decisions at an aggregate, national level. This likely reflects an anxiousness to “harmoniously” balance interests. However, as I will show, all else being equal, places with high labour unrest do not follow this pattern and instead rule fully for workers.

Figure 4: Outcomes of Formally Adjudicated Employment Disputes in China, 2003–2012

Controls Used

A number of factors could conceivably both spur or dampen resistance and shape state reactions to it. For example, a booming economy might at once yield both more strikes and more state responsiveness without there being a causal relationship between the two. It is a truism in industrial relations theory that workers are more willing to engage in work stoppages when they have other job options, i.e. when local economic conditions are good.Footnote 52 Growth also generally means more tax revenues and therefore a greater ability on the part of authorities to satisfy workers – or pay for security forces to suppress them. Thus, William Hurst has shown how during China's SOE restructuring of the late 1990s and early 2000s, well-off local governments did a better job of compensating and retraining laid-off and angry employees.Footnote 53 One can further imagine that wealthy areas might be less concerned about offending businesses by siding with workers, as such places can always attract other investment. To control for all this, I include in my analysis the natural log of provincial gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.

The presence or absence of particular groups of workers might also confound my analysis. Studies have highlighted the militancy of migrant workers and SOE workers, in particular.Footnote 54 It seems likely that authorities will also react differently to protests from these groups: migrants are less embedded in local political structures than locals and therefore possibly are less of a concern for officials,Footnote 55 while SOE workers have a strong “moral economy” claim to official attention.Footnote 56 Yuhua Wang has already demonstrated that there is a correlation between downturns in SOE employment and upticks in police expenditures.Footnote 57 There might also be less reporting on conflicts involving the state sector, biasing my measurement of unrest. For these reasons, I control for the percentage of a province's residents with household registration somewhere other than where they live or work and the percentage employed in SOEs.

In addition, certain institutions could affect resistance and responsiveness at once. Chinese labour NGOs have expanded their above-ground activities in recent years from legal training for workers to more risky engagement in collective action.Footnote 58 Their presence in a region could conceivably both spur more worker activism and make the state respond less sympathetically (more repressively) to unrest. I therefore include a control for the number of NGOs in a given province in a given year, using a list of groups and their founding dates provided by the CLB.Footnote 59 The ACFTU is often a non-entity in the country's industrial relations, but at its most active it mediates between capital and labour, standing fully with neither side (but always with the government).Footnote 60 As such, it might both factor into workers’ decisions about whether to strikeFootnote 61 and affect how strike demands are handled by employers and officials. I thus furthermore control for the number of enterprises with wage-only collective contracts in a given province in a given year.Footnote 62

Less easily categorized potential confounders also exist. For example, there may be variation across regions and across time with regards to the abuses suffered by workers, and this variation might in turn affect variation in both the strength of the cases that are formally adjudicated (and therefore workers’ win rate) and the number of strikes, protests and riots that occur. There is no perfect solution for this issue. However, to partially deal with it, I include a control for the percentage of cases featuring the single type of claim with the most intra-provincial variation, namely remuneration (wage arrears, etc.). More populous provinces, meanwhile, will likely have more strikes, spend more on the police, and experience more disputes of all types, so I control for the natural log of provincial population. Finally, urban areas may have higher crime, more sophisticated judiciaries and other characteristics that would affect my results. I therefore include in my analysis the percentage of a province's population living in urban areas.Footnote 63

Models

In the next section, I show how resistance, repression and responsiveness, as captured by the measures explained above, tend to move together. With full controls, my models take the following form:

where i is the province and t is the year, ΔY t is the year-to-year change (first difference) in either provincial PAP spending or the number of disputes in a given province that have a particular outcome; α 0 is the intercept; β 0 is the coefficient of the year-to-year change in my main independent variable, strikes; β 1 is the coefficient of a vector containing all my controls; and εit is the error term. I use the change in my dependent variables and my main independent variable because Augmented Dickey-Fuller and Phillips-Perron unit root tests show evidence of non-stationarity in my time series, meaning that they have secular trends that might lead us to imagine causal relationships between them where there are none (this should not surprising: as already demonstrated, strikes, police spending and dispute decisions of all types are steadily rising). First-differencing furthermore makes year fixed effects unnecessary.

Results

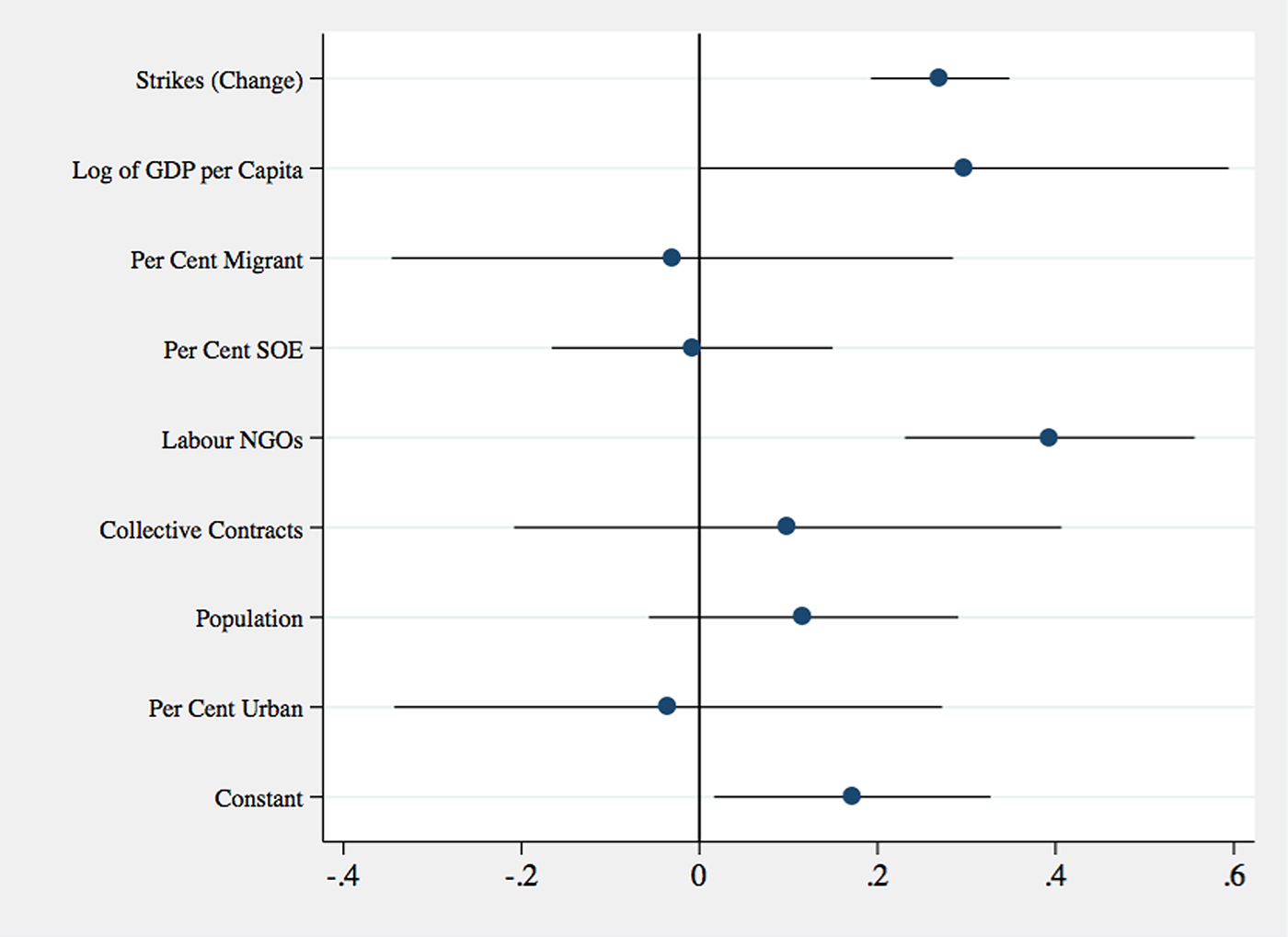

The results are clear. Worker resistance is associated with both greater repression and greater state responsiveness towards workers, as theorized. With regard to spending on the PAP, Figure 5 plots the standardized coefficient of strikes and of each of my controls, along with their 95 per cent confidence intervals. Variables with their coefficients to the right of the zero line in the figure have a positive correlation; those to the left, a negative correlation. Confidence intervals that cross the zero line are insignificant (i.e. they are not significantly different from zero). Strikes show a positive, significant correlation with police spending. Specifically, an increase of one strike in my China Strikes dataset is correlated with an increase of 4.8 million yuan in funding going to the PAP (p < 0.001). In a similar manner, Figure 6 plots the standardized coefficients of my various independent variables with regard to pro-worker, pro-business and split outcomes in employment disputes. Strikes are demonstrated to have a significant, positive correlation with both pro-worker and split decisions, but are not significantly correlated with pro-business decisions. Despite the aggregate, national trend towards split decisions, the coefficient for pro-worker decisions is also highest. Specifically, an increase of one strike in my dataset is associated with an increase of 130 disputes decided in a pro-worker manner and 66.2 decided in a split manner (p < 0.01). Of course, my strike dataset is, again, only a sample, and a single strike among the full “population” of strikes in China likely has much less impact.

Figure 5: Strikes and People's Armed Police Spending, 2003–2009

Figure 6: Strikes and Formally Adjudicated Dispute Outcomes, 2003–2012

There are interesting ancillary findings, too. With regard to repression, besides strikes only one other variable is significant: an increase of a single labour NGO in a province is correlated with an increase of 10.7 million yuan in PAP spending (p < 0.001). This shows the government's extreme anxiety over these groups. Regarding dispute outcomes, a higher percentage of migrant workers in a province is correlated with fewer pro-business and split decisions and has a negative but insignificant correlation with pro-worker decisions. This suggests a dampening effect of migrant density on employment litigation more generally, when other factors are controlled for, in line with studies by Mary Gallagher and others suggesting that although migrants are catching up, locals are still somewhat more knowledgeable about the law (especially when low-educated migrants and low-educated locals are compared).Footnote 64 Meanwhile, higher GDP per capita is associated with more split decisions but has no significant correlation with pro-worker decisions. Perhaps wealthy provinces can afford to try to please everyone. Strangely, NGOs show the same association. This may be because they can only achieve compromises through mediation in many cases, as shown by Aaron Halegua.Footnote 65 Finally, a larger percentage of urban residents is correlated with both more pro-worker and split decisions. The percentage of cases featuring remuneration claims has no significant relationship with dispute outcomes. Neither do state-owned enterprise employment, union contracts or population. Strikes stand out in the degree to which they predict both increased repression and responsiveness.

Reverse Causality

The results above need to be checked for reverse causality, meaning the possibility either that PAP spending or more pro-worker or split decisions actually encourage greater unrest instead of the other way around, or that there is a two-way relationship between state and worker actions, generating an endless loop of cause and effect. It might seem that greater investment in paramilitary forces would, if anything, deter protests. Certainly, few of the incidents in my dataset appear to be directly driven by grievances related to policing (40 incidents, or under 3 per cent). However, some theories of state coercion suggest that it gradually pushes activism in a more radical direction.Footnote 66 At any rate, one can certainly imagine that employees might be buoyed by positive outcomes in formally adjudicated disputes. Workers could interpret these decisions as evidence of state support – what social movements scholars call an opening in the “political opportunity structure”Footnote 67 – and therefore take to the streets in yet higher numbers.

The best way around this and other identification issues is to use an Arellano-Bond estimator. This is designed for situations where there are a small number of time periods and a large number of individuals (here, individuals are provinces); where there are right-hand-side variables that may not be strictly exogenous (in this case, strikes); and where differencing may have introduced autocorrelation (an additional problem). The model includes a lagged dependent variable (PAP spending or dispute decisions at time t-1) to address autocorrelation, and it deals with endogeneity by instrumenting strikes with past levels of strikes (two lags back).Footnote 68 It can thus give much greater confidence in my findings, while highlighting important nuances.

When I run Arellano-Bond regressions, I get almost exactly the same results for PAP spending as I did with the simpler model (p < 0.05). In other words, paramilitary spending does not appear to significantly increase the level of unrest as some would expect – or decrease it, for that matter (although coercion may change the form that the activism takes, for example push it in a more violent direction, something which cannot be tested with my data). However, when I use the estimator with the different formally adjudicated dispute outcomes, things change. Specifically, strikes are no longer significantly correlated with pro-worker decisions or split decisions, but they become both significantly and negatively correlated with pro-business decisions (p < 0.01). In other words, there seems to be strong reverse causality at work with regard to any dispute outcome that gives something to workers. Political opportunity signals matter. But worker mobilization is nonetheless driving down straight-out employer wins, in line with my theory.

Further Robustness Checks

There are two more issues to resolve. The first is that some residual regional bias in reporting incidents might be skewing things. To check for this, I re-run the regression with provincial fixed effects included, and the results are the same. In addition, I use the total number of formally adjudicated employment disputes in the place of strikes. As I have noted, many strikes spill directly into the courts and vice versa, and the two variables are fairly tightly correlated (if less so in recent years). The result: more disputes are, of course, significantly correlated with more of all of the possible dispute outcomes, but the coefficients for pro-worker and split decisions (0.3 and 0.37, respectively) are much higher than for pro-business decisions (0.08). However, there is no significant relationship between disputes and PAP spending, although the correlation is in the same direction. Despite the fact that this runs contrary to my previous findings, it should not be surprising. Workers taking cases through the legal route instead of to the streets lessens the pressure on the public security apparatus. The second, related issue is that a few influential observations could be driving the results. However, if I drop the small number of observations with more than 50 strikes per province / year, my results remain the same (p < 0.05). In other words, this is not just a story of a few hotspots.

Changes under Xi Jinping

One final matter is worth addressing: how things have or have not changed under the current Xi Jinping government. As noted, the data used in my statistical analysis only cover the Hu–Wen era. However, the CLB strike map, which I have checked my data against for the years we overlap, shows a persistent increase in unrest through the year 2017. As Figure 2 showed, the growth in strikes, protests and riots overtook that of formally adjudicated employment disputes already in 2008. This trend seems to be continuing. But, formally adjudicated disputes are also on the rise again, surpassing their level in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis. Again, there are no provincial-level PAP figures publicly available after 2009. More general public security spending figures continue to climb, but at least for the early years of this administration, the correlation between these figures and unrest becomes insignificant at the provincial level, likely as a result of the centralization of security under Xi.Footnote 69 Nonetheless, there is anecdotal evidence that repression has intensified considerably in hotspots of contention. In December 2015, for instance, several leading labour NGO leaders in the vicinity of Guangzhou were detained. One, Zeng Feiyang 曾飞洋, was vilified in the media and, after nine months in jail, was given a three-year suspended sentence; another, Meng Han 孟晗, was given a 21-month sentence.Footnote 70 Researchers for the New York-based China Labor Watch were also detained for the first time in China in 2016, stemming, it seemed, from investigations conducted in Jiangxi and Guangdong. In 2018, the government arrested scores of striking workers at the Jasic electronics factory in Shenzhen, along with their student supporters. Then, in January 2019, more labour NGO leaders were detained, also in Shenzhen. At a national level, both pro-worker and split decisions continue to far outstrip pro-business decisions. Without updated strike data of my own, it is difficult to tell whether straight-out employee wins still tend to concentrate in high unrest areas. Nonetheless, anecdotally, the government appears to persist in making other sorts of conciliatory gestures to workers, albeit not dramatic ones. No protective legislation on the scale of the 2008 Labour Contract Law has been passed, but a 2015 document on “Constructing harmonious labour relations” jointly released by the State Council and CCP Central Committee bolstered several existing trade union reforms.Footnote 71 Tellingly, the government has slowed a planned round of SOE layoffs in the steel and coal sectors following activism by miners in Heilongjiang in 2016.Footnote 72 And new, restrictive national rules on the taxi sector and ride-hailing apps seem to be a direct response to cabbie protests.Footnote 73 Resistance is continuing to yield both repression and responsiveness. However, of the two government reactions, repression seems to very much be taking the lead.

Conclusion

My article has shown that increases in strikes, protests and riots are correlated at the provincial level with more spending on the People's Armed Police and more pro-worker and split decisions in mediation, arbitration and court. However, rulings in favour of workers in turn spur more workers to take to the streets. Changes under Xi indicate that although China's dual approach to control carries over from leader to leader, the precise balance between repression and responsiveness may alter. Perhaps cognizant of the feedback effect already noted, conciliatory gestures by the state, while still evident, seem to have cooled in recent years, while harsher crackdowns have been launched against activists.

These findings have several immediate implications for researchers. First and most basically, authoritarian states clearly do not necessarily face a binary choice over how to react to unrest. They can proceed along two tracks at once: repressive and responsive. Second and relatedly, the picture for worker-activists is more complicated than either the more optimistic or more pessimistic recent interpretations of researchers might lead us to believe. Third, the fact that positive rulings inspire even more unrest bolsters social movement scholars’ work on “opportunity spirals” and suggests that there is a cost for authorities of greater responsiveness.Footnote 74 Fourth, the lack of any demonstrated feedback effect with regard to police spending suggests there is no immediate cost to repression (it does not spur a higher level of resistance), but then again, repression is not found to offer clear benefits either (it does not reduce resistance). This complicates existing research on policing and radicalization.Footnote 75 But these are just the most immediate takeaways.

In an indirect manner, the article also contributes to our understanding of state capacity building. In his study of South-East Asian authoritarian regimes in the post-war era, Dan Slater argues that social movements can build the state just as surely as wars can.Footnote 76 Specifically, he shows that urban insurgencies that activated ethnic cleavages spurred nervous elites to rally into “protection pacts” around some of those regimes and thereby aided the consolidation of state power (in part via enhanced revenue extraction from the same elites). Worker activism in China is still too fragmented to have this sort of result. Moreover, Chinese elites are arguably not coherent enough to function as a clear base of support for anyone. And ethnicity is not an important factor in urban China (although it is on the periphery). Nonetheless, we can imagine that increased use of and investment in the government's tools of coercion and conciliation might result in increased facility with these tools over the long term. Already, there is evidence that police in China are being deployed in an increasingly sophisticated manner, although the upgrade has been gradual and halting.Footnote 77 Courts, meanwhile, are becoming more and more professionalized, at least with regard to some areas of law.Footnote 78 This article suggests it is not just business pressures that are driving this professionalization. State-capacity building is a generic feature of modernity, but labour activism may be speeding it up in China – and in recent years, especially in the area of repression – with the unintended effect of strengthening the Chinese authoritarian leviathan.

Yet, there is reason to believe this strengthening will prove unsustainable in the long term. Repressive and responsive capacity are only two forms of the many forms of state capacity that are important, after all. In their classic study, Gabriel Almond and Bingham Powell list the others: extractive capacity (Slater's focus), distributive capacity (the state's ability to redirect the gains of economic development), and symbolic capacity (the ability to build buy-in for the state's mission).Footnote 79 By devoting such tremendous resources to threatening and bribing protesters, the Chinese government may be putting off developing these other critical dimensions of its power. In fact, increased repressive and responsive capacity might actively undercut progress in several areas. For example, a state that constantly makes new social commitments but cracks down on people when they try to realize those commitments will have difficulty symbolically.Footnote 80 With Xi Jinping in charge, as noted, repression is apparently being emphasized over responsiveness. This may seem a cautious style of governance, but there are trade-offs. Money spent on police is money not spent on other priorities, like social programmes that redistribute wealth and deal with popular grievances at a more fundamental level. Xi's approach may thus carry significant long-term risk. For activists and authorities alike, the dynamics documented in this article present both new opportunities and challenges. Even as they make gains, activists are presently experiencing severe challenges; authorities could experience much greater challenges in the future.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant from the National Science Foundation (Award Number #1421941), a Hu Shih Memorial Award and Lee Teng-hui Fellowship in World Affairs from Cornell University's East Asia Program, travel grants from Cornell's ILR School and the Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies, and a China Public Policy Postdoctoral Fellowship from Harvard University's Ash Center. I am especially grateful for feedback on previous drafts from Marc Blecher, Steffen Blings, Valerie Bunce, Greg Distelhorst, Peter Enns, Eli Friedman, Yao Li, Andrew Mertha, Sara Newland, Freya Putt, Sidney Tarrow, William Hurst, Chengpang Lee, Junpeng Li, Emmanuel Teitelbaum and Jeremy Wallace, as well as my two reviewers. Rebecca Zhang provided invaluable assistance with data collection. Any mistakes are my own.

Biographical note

Manfred ELFSTROM is a postdoctoral scholar and teaching fellow at the University of Southern California's School of International Relations. His research interests include labour, social movements and authoritarianism.