The core of the cross-Taiwan Strait rivalry since 1949 is the two sides’ ultimate political relations, known as the “one China” issue. Before the 1970s, China and Taiwan had threatened and used force against each other in this dispute. In the 1970s, as detailed in this special section, a critical wave of developments catalyzed by US President Richard Nixon's 1972 visit to China resulted in a vague international framework on the “one China” question that helped subdue cross-Strait military tensions.Footnote 1 Nonetheless, China has never renounced force to solve the dispute and has stepped up military pressure on Taiwan again in recent years. As Taiwan and its security partners gear up to resist China's coercion and sustain the island's autonomy, the “one China” issue has kept the Taiwan Strait a flashpoint in East Asia.

Cross-Strait hostility might manifest politically and militarily in forms similar to the past; however, its nature and dynamics have changed significantly. Since Tsai Ing-wen 蔡英文 took Taiwan's presidential office in 2016, cross-Strait relations have plummeted into a deep freeze. The apparent reason is Tsai's unwillingness to use the so-called “1992 Consensus” to describe the two sides’ relationship.Footnote 2 In 1999, China similarly suspended political contact and mounted military pressure on the island when Taiwan's then president, Lee Teng-hui 李登輝, described cross-Strait relations as “a special state-to-state relationship.”

Such seemingly trivial disputes over the wording that describes cross-Strait relations were also witnessed in attempts at reconciliation and proved to be a fundamental barrier to improved relations. In 2001, Taiwan's then president, Chen Shui-bian 陳水扁, proposed a possible “future one China,” but Beijing rejected this overture. Between 2008 and 2016, when Taiwan's then president, Ma Ying-jeou 馬英九, subscribed to the “one China, different interpretations” formulation of cross-Strait relations, China and Taiwan enjoyed a rapprochement. Still, Beijing was uncomfortable with Ma's emphasis on the “different interpretations” and, as a result, allowed Taiwan little more international space, which eventually led to the détente's collapse.

The formulations used to describe cross-Strait relations have ostensibly become the focus of China and Taiwan's dispute. The various proposed frameworks – the 1992 Consensus, “special state-to-state relationship,” “future one China” and “one China, different interpretations,” to name a few – seem to be petty arguments over words that, nonetheless, lead to continuing stalemates. Why can China and Taiwan not set aside their quibbling over the semantics of how Taiwan's status relative to China is described? Why can Taipei not commit to the 1992 Consensus, or even “one China,” especially if this will likely ease strained cross-Strait relations and not change the facts on the ground that Taiwan has de facto independence? Similarly, why can Beijing not accept a “future one China” or recognize that Taipei possesses sovereignty as it does, considering, for example, that the two Germanies during the Cold War adopted this solution and ultimately arrived at unification?

This paper argues that the quibbling goes beyond its seeming triviality and reveals the fundamentally transformed nature of the cross-Strait “one China” dispute. In what follows, the paper first points out that the extant explanations leave a precise understanding of the conflict's essence wanting and argues that the nature of the “one China” dispute has transformed from indivisible sovereignty to a “commitment problem.” In a nutshell, China and Taiwan worry that concessions will strengthen their rival's cause and weaken their own future bargaining leverage on the “one China” dispute. Beijing thus hesitates to budge on the formulations of cross-Strait relations because it worries that any concessions on its “one-China principle” would enhance Taiwan's statehood internationally and enable the island to push forward with de jure independence. Similarly, Taipei worries that any perceived concessions on the question of “one China” would enhance China's sovereignty claim over the island and allow Beijing to push for unification coercively with fewer concerns about international backlash. Such dynamics manifest a quintessential commitment problem in international politics. The paper then traces the commitment problem's perils to Beijing's and Taipei's respective domestic politics, followed by two case studies to illustrate the better explanatory power of the commitment problem argument when compared to its alternatives. Finally, the paper concludes with policy suggestions for managing this precarious dyadic relationship of a transformed nature.

The Changed Nature of the Cross-Strait “One China” Dispute

China's official documents invariably ascribe a historical nature to its fixation on Taiwan's status. For example, in “The Taiwan Question and Reunification of China” white paper issued in 1993, Beijing called the “one China” issue a question “left over from history.”Footnote 3 The cross-Strait dispute is described as a relic of the Cold War and the remains of the unfinished Chinese Civil War. However, the ideological competition that characterized the Cold War has long become anachronistic. Moreover, Taiwan has relinquished its effective sovereignty claim over the Chinese mainland since 1991, putting the civil war cause to rest. Nonetheless, these historical changes have not removed the “one China” issue from the Taiwan Strait or the international system. Therefore, a purely historical interpretation is insufficient to understand the lasting presence of the cross-Strait “one China” dispute.

As Liff and Lin and Chen detail in this special section, the “one China” issue emerged in world politics after the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT) government took exile to Taiwan in 1949.Footnote 4 Despite belonging to different camps during the Cold War, both sides of the Taiwan Strait were under authoritarian rule. Things changed in the late 1980s when Taiwan gradually democratized, and the new generations born on the island lost all connections with the Chinese mainland. The majority of Taiwanese now loathe the prospect of losing their way of life were Taiwan to be folded into the authoritarian mainland China. In fact, as Shelley Rigger points out, many Taiwanese citizens “see little benefit in giving up what they have to become part of any Chinese state headquartered on the mainland – even a non-Communist one.”Footnote 5 Thus, many commentators have argued that Taiwan's changing identity, which has become increasingly incompatible with a Chinese identity centred on mainland China, is now the essence of the cross-Strait “one China” issue.Footnote 6

Beijing has periodically accused Taipei, especially during pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) administrations, of pursuing “de-sinicization.” China's responses to measures claimed to deny Taiwan's ethnic, cultural and historical bonds with China often heightened cross-Strait tension and highlighted the role of identity in the dispute. However, while diverging identities matter, they are not the source of rivalry without being politicized in the first place. As Rigger contends, a “pro-Taiwan” identity does not necessarily equal an “anti-China” identity.Footnote 7 For instance, studies have found that not all advocates of a unique Taiwanese identity have supported restrictive economic measures against China.Footnote 8 Were divergent identities to lead to rivalry reflexively, this group of people should be particularly wary of the island's economic dependence on China, which is not shy about using economic integration to promote identification with the mainland. Therefore, a clear theoretical understanding of how such divergent identities persist and exacerbate the cross-Strait “one China” dispute and hinder reconciliation is still lacking.

Moreover, identity-led arguments often confuse a “Taiwanese identity” with “Taiwanese nationalism.” Research has found that, despite a distinctive Taiwanese identity that has become dominant on the island, a large part of Taiwanese society is pragmatically open to both independence and unification with some conditions.Footnote 9 Thus the core of the “one China” dispute does not rest on identities per se but rather on the political conditions acceptable to both the people in Taiwan and the ruling group in China.

Unable to compromise with acceptable political conditions, Beijing has threatened force should Taiwan move towards de jure independence and declared it will never renounce the use of force to achieve unification. The “one China” issue thus poses an existential threat to Taiwan. However, viewing the “one China” dispute as a security issue confuses consequences with causes. Taiwan and China's inability to find a compromise on “one China” leads to mainland China's continuing security threat to the island. The security threat may be the most tangible manifestation of the conflict. Still, it is not the source of the “one China” dispute. This argument is not to belittle China's security threat to Taiwan. Nor does it slight the importance of Taiwan's defence preparation and the US's deterrent capabilities in dissuading Beijing from resorting to force to solve the “one China” dispute. A secured Taiwan might also be more willing to go to the negotiating table with China. Nonetheless, maintaining military balance does not equate to finding an acceptable settlement.

Relatedly, a geostrategic explanation contends that Taiwan's geographic location, which could impede China's free access to the open ocean, explains Beijing's fixation on Taiwan's status.Footnote 10 However, as Alan Wachman summarizes, this is premised on the line of reasoning that the island is “in hostile hands.”Footnote 11 The geo-strategic explanation thus highlights the consequences more than the causes of the “one China” issue because cross-Strait reconciliation could mitigate Beijing's concern regarding the island being used as a staging area for hostile forces. Furthermore, recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign entity also does not rule out China's use of the island to access the open ocean. An alliance is one way, but not the only way, in which it can occur.

As mentioned already, the cross-Taiwan Strait “one China” rivalry began in 1949. Back then, both regimes across the Strait – the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan and the People's Republic of China (PRC) on mainland China – claimed that Taiwan was part of “China's” territory, and, therefore, that the two sides of the Strait belonged to the same sovereign state. They disagreed upon who held the sovereignty of “China” and legitimately represented the whole of “China” in the international system. In other words, the rivalry began as an issue of indivisible (or competing) sovereignty.

Taiwan's democratization starting in the late 1980s ushered in fundamental changes to the core of the dispute. The democratic procedure empowered the island's indigenous independence movement. It made the voice of Taiwan independence a legitimate political force to be reckoned with. Meanwhile, in 1991, Taipei conceded the PRC's rule over mainland China and put the ROC's competition with the PRC to represent the whole of “China” to rest. At that point, Taipei had lost the capabilities for such a quest. More importantly, it no longer had an interest in such an endeavour. Instead, to protect the island's citizens' political interests in the world in the face of the PRC's growing international prominence, the ROC tried to carve out an international status that was not contingent on jurisdiction over mainland China.

However, Taiwan's renunciation to compete with the mainland to represent “China” did not resolve the “one China” issue. Instead, these political changes gave Beijing worries about Taipei's commitment to remaining part of “China.” As Chen documents in this special section, Beijing took Taipei's decoupling from the international competition over “China's” representation as a ploy to undermine its sovereignty claim over Taiwan.Footnote 12 As a result, Beijing responded with increasingly stringent enforcement of its “one-China principle” in international affairs, feeding into Taiwan's resentment and frequent challenges to Beijing's “one China” shackles in the international community.

In brief, though the “one China” issue remains the sour point of cross-Strait relations, its nature has moved away from overlapping sovereignty claims. The changed nature has brought in new dynamics to the conflict.

The Cross-Strait Commitment Problem

To understand the transformed nature of the current cross-Strait “one China” issue, one must first clarify each side's preferences in the conflict. China's most preferred outcome in the “one China” dispute remains to make Taiwan part of the PRC, which essentially means Taiwan will forgo its international personality, that is, transferring the authority to conduct international diplomacy entirely to Beijing's central government.Footnote 13 Before 1979, China pursued unification by force. Since then, Beijing has shifted its strategy to peaceful unification, with a proclaimed formula of “one country, two systems.” However, despite the preference for a peaceful solution, China has never renounced force to achieve unification. In its 2005 Anti-secession Law (Fan fenlie guojia fa 反分裂国家法), Beijing has laid out several non-specific conditions that will trigger its use of force against Taiwan, including when Beijing perceives the possibility of peaceful unification has disappeared.Footnote 14

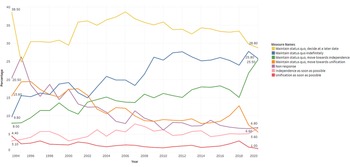

Taiwan's preferences in the “one China” dispute, like the international practises of “one China” documented in the rest of this special section,Footnote 15 have evolved over time. Notably, since the early 1990s, opinion polls conducted by the Election Study Center (ESC) of Taiwan's National Chengchi University have continuously shown that supporters of immediate unification have been few in Taiwan, and the number had declined to around one per cent of Taiwanese citizens in December 2020 (Figure 1). The majority have supported the “status quo” instead. However, they differ on the preferred terminal political status of the island.Footnote 16

Figure 1. Taiwan Citizens’ Preferred Terminal Political Status of the Island

Sources: ESC 2020.

Breaking down the status quo supporters in the ESC polls, one will find that supporters of “maintaining the status quo indefinitely” and “maintaining the status quo and moving towards independence” have steadily increased from one-fifth of the population in 1994 to almost one-half in 2020. Another one-third of the population has wanted to maintain the status quo and decide on Taiwan's political relations with China later.

Here, one can consider another gauge of Taiwan's preferences on the “one China” issue. According to Duke University's 2019 Taiwan National Security Survey (TNSS), 62 per cent of respondents supported Taiwan's independence if declaring independence would not court China's invasion. Meanwhile, the same survey showed that even if mainland China's political, economic and social conditions were similar to Taiwan's, 67 per cent still did not support unification.Footnote 17 Thus, one can infer from the TNSS outcomes that a significant portion of those who support the status quo now and prefer to defer the decision on Taiwan's status would not opt for unification even if the cross-Strait institutional difference were minimal. In sum, from the above survey data, one can deduce that the ideal outcome for most Taiwanese in the “one China” dispute is to maintain and strengthen Taiwan's autonomy and international personality, with or without an affiliation with China.

China and Taiwan, therefore, have contrasting preferences on the “one China” issue. The opposite preferences and China's threat of force to solve the difference make the rivalry one with a high expectation of conflict. Nevertheless, the diametrical preferences do not mean a reconciliation is not preferable – quite the opposite. The history of cross-Strait relations is fraught with tensions that risk stumbling into armed clashes and wreaking havoc on both sides. Reconciliation is thus an attractive option as long as neither side is risk-seeking.

A cross-Strait compromise is also possible because the above ESC opinion polls in Taiwan have continuously shown that the majority of the population are pragmatic supporters of the status quo. In comparison, the support for immediate independence has been low. Such survey outcomes indicate that the Taiwanese are willing to compromise on formal independence so long as they can continue enjoying de facto autonomy.

A compromise is also acceptable to China. Beijing indeed prefers to end Taiwan's separation from the mainland. However, as Rigger argues, Beijing's current bottom line remains to keep Taiwan connected to China to preserve the possibility of unification someday.Footnote 18 Besides, stable cross-Strait relations ensure that China can reap the benefits from Taiwanese technology and a more benign regional environment to continue growing its national strength. The fruition of the latest cross-Strait détente between 2008 and 2016 testifies that reconciliation is preferable and possible.

The puzzle is that cross-Strait rapprochements have been rare and short-lived. The literature has pointed to mistrust as the key hurdle to improved relations. For Taiwan, the danger in a rapprochement is that Taipei might assume China is prepared to accept some version of the status quo over the long haul while Beijing's objective remains to end Taiwan's de facto independence on Beijing's terms. China might then exploit the power asymmetry (presumably exacerbated by a rapprochement) and intimidate Taiwan into accepting “an offer it can't refuse” once Beijing exhausts its patience.Footnote 19 As for China, it worries that Taipei will exploit the wider international space resulting from a rapprochement to pursue formal independence.Footnote 20

The research here illuminates the core of this mistrust. High conflict expectations incentivize both rivals to be concerned with their future bargaining positions. As a result, when China and Taiwan contemplate rapprochement, they worry about any concessions’ distributional consequences for their future standing in the dispute.Footnote 21 In essence, what impedes the two from initiating and sustaining a détente are concerns about the commitment problem in international politics.Footnote 22

Under anarchy, a state cannot credibly commit itself not to exploit the greater bargaining leverage it will gain after its rival makes unilateral concessions. To borrow Herman Kahn's words, both China and Taiwan fear that trusting their rival and placing it in a position to make gains from one's concessions can awaken the rival's greediness and make them vulnerable to the rival's future defection.Footnote 23 Scott Kastner and Chad Rector have pointed out how the difficulty in making credible future commitments might hinder a negotiation over unification.Footnote 24 However, when China and Taiwan see no possibility of solving their “one China” disagreement in the near term and only try to mothball their rivalry, the commitment problem still looms large.

Given that neither China nor Taiwan is ready to give up its claims in the “one China” dispute, a rapprochement merely suspends their confrontation to buy time and prospects for reconciliation. Both sides have proclaimed that their preferred mechanism for finding an eventual solution is “negotiation in parity.”Footnote 25 However, reflecting their respective bottom lines discussed earlier, China and Taiwan emphasize different parts of this mechanism. Taiwan wants to see parity before entering negotiation to ensure its autonomy is recognized. In contrast, China wants to negotiate the arrangements for parity to ensure Taiwan will operate within the confines of Beijing's “one-China principle.” Both are hesitant to make one-sided concessions to the other side's preference because at stake are their causes’ international validity and the two governments’ domestic legitimacy.

Specifically, Taiwan worries its concessions on “one China,” if even semantically, will promote the international recognition of Beijing's sovereignty claim over the island. International recognition of China's sovereignty over Taiwan will reduce Beijing's political costs in taking coercive actions to subdue the island. It also helps China circumvent the taboo against conquest by making the dispute ostensibly a PRC's internal affair.Footnote 26 These conditions will give Beijing a stronger position to impose its ideal solution to the “one China” dispute while weakening Taiwan's capabilities to resist. Recent developments in Hong Kong, where Beijing has experimented with its “one country, two systems” formula, epitomize Taiwan's worries. Following the protracted pro-democracy demonstrations in 2019, Beijing wilfully imposed the National Security Law on the territory to crack down on all dissent despite promising Hong Kong considerable political autonomy when Britain handed over the territory in 1997.Footnote 27 Facing pushbacks led by major democracies, Beijing claimed the measures were within the purview of its internal affairs and gained support from another larger group of countries, blunting the international fallout.Footnote 28 As Alan Romberg indicates, critical to Beijing regarding the “one China” issue is not realizing actual reunification but establishing sovereignty over Taiwan because, under its sovereignty, reunification is something to be handled as an “internal” matter, “on a timetable and via methods to be determined by them alone.”Footnote 29

For that same reason, China worries its concessions on “one China” will strengthen Taiwan's status as an independent state in the international community. Increased international recognition of Taiwan's statehood will make it more costly for China to take coercive actions to deprive Taiwan's autonomy. Member of the European Parliament Raphael Glucksmann's statement that “the more you have interaction between the international community and Taiwan, the less dangerous the situation would be in the Strait” reflects this logic squarely.Footnote 30 Even if the two eventually negotiate unification, international recognition of Taiwan's statehood will enhance the island's bargaining position vis-à-vis China.Footnote 31 Therefore, even for Ma Ying-jeou, who favoured eventual union with the mainland and oversaw a cross-Strait rapprochement in his two-term presidency, Taiwan's international participation that increased other countries’ stakes on the island's autonomy was crucial.Footnote 32

It is noteworthy that, as a deeply involved third party, for decades Washington's priorities on ensuring cross-Strait stability (or a peaceful resolution) but not necessarily the status quo have seen US rhetoric and attitudes towards Taiwan's international status that are varied and sometimes inconsistent, often contingent on the climate of Sino-US relations.Footnote 33 The ambiguity has fuelled suspicions on both sides of the Strait – improved Sino-US relations often make Taipei worry about Washington's assurances on supporting its autonomy while the opposite trends make Beijing suspicious about US intentions on this issue – and has not helped with the commitment problem.

In sum, concessions in rapprochements can greatly legitimize the rival's cause internationally and reduce its costs of taking forceful actions to pursue its preferred solution to the “one China” issue. Thus China and Taiwan worry that, after their concessions give the rival advantage in international standing, the rival will not resist its self-interest in using the improved position to return to confrontation, drive a hard bargain, and force a disadvantageous resolution that they have to accept. This quintessential commitment problem is what now persists and exacerbates the cross-Strait “one China” stalemate.

The Cross-Strait Commitment Problem and Domestic Political Costs

For Beijing and Taipei, the fundamental costs of overlooking the commitment problem come from their domestic politics. Since Deng Xiaoping's reform and opening up, the CCP has abandoned communism in all but name. In place of ideology, the Party has relied on its performance in achieving economic and nationalist goals for its legitimacy. The CCP claims to be the party that led China to win the “War of Resistance against Japan,” redressed the “century of humiliation,” and successfully reunited the country.Footnote 34 Through propaganda and patriotic education, the Party has indoctrinated the Chinese people with its image as the only and best safeguard of national unity and the vanguard of returning China to greatness to legitimize its rule. Thus, the “one China” issue and Taiwan's political status, which for Beijing symbolize China's sovereignty and territorial integrity, are intrinsically linked to the CCP's nationalist credentials and regime security.Footnote 35 As Rigger concludes, by “emphasizing unification so strongly and making the ‘rectification’ of this ‘vestige of humiliation’ a primary goal of national development, PRC leaders have turned the Taiwan issue into a yardstick by which their own performance is measured.”Footnote 36

Moreover, the party-state no longer monopolizes nationalist politics in the country. Popular nationalists in China do not merely support the nationalist claims propagated by the party-state. They also issue their claims and thus challenge the party-state's policies and legitimacy.Footnote 37 Even though the CCP maintains tight control over society, suppressing popular nationalist challenges could be costly, especially when these challenges are framed around the nationalist causes inculcated by the party-state.Footnote 38 As a result, the party-state often needs to accommodate popular nationalist demands and demonstrate that it defends China's national unity and honour to win domestic audiences’ support and solidify regime legitimacy.Footnote 39 The US's accidental bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in a NATO mission in 1999 exemplifies such a nationalist challenge. The bombing led to widespread bottom-up protests that the Party was hesitant to suppress. Unable to control popular anger, the CCP was forced to appease the resulting nationalist demands while pleading with protestors for calm.Footnote 40

Though Susan Shirk points out how nationalist anger over a Taiwan crisis might bring down the CCP regime has rarely been specified, the pervasive belief that losing Taiwan will lead to apocalyptic popular outrage and prevent the regime's survival has created its own political reality, at least amid the Party leadership.Footnote 41 As a result, “more than once, the fear of making one-sided concessions has caused the PRC to miss opportunities to improve relations with Taipei.”Footnote 42 Even on the rare occasions of initially successful détente, Beijing straitjacketed its concessions on Taiwan's international space to prevent any domino effects that might bring down Beijing's claim that the “one China” dispute is purely a PRC internal issue, in fear of promoting Taiwan's separate statehood and precipitating a Taiwan crisis. Unfortunately, the results were often too-little-and-too-late compromises that made Taiwanese people wary of losing ground and instigated Taiwan's fear of the commitment problem. Mistrust thus re-emerged and brought down the rapprochement.

One critical item of evidence exhibiting China's concerns about the commitment problem is Beijing's dual messages to Taiwan versus the international community. In response to domestic developments in Taiwan that unfolded in the 1990s and the changing nature of the “one China” issue, the PRC subtly adjusted the definition of its “one-China principle” in the early 2000s. The critical element of these adjustments was Beijing's restraint from asserting to Taipei that the PRC was the only legitimate government of China.Footnote 43 The revised version in 2000 stated that “there is only one China in the world; both the mainland and Taiwan belong to this one China, and China's sovereignty and territory cannot be divided.”Footnote 44 The altered definition implies that, at least in its rhetoric directed towards Taiwan, the PRC has stopped explicitly equating the “one China” to itself and left potential room for the two sides of the Strait to negotiate and create a “China” of which both are comfortable being part.Footnote 45

However, towards the international community, the PRC's messages have continued to be forceful and loud in expressing that it is the only legitimate government representing “China” and that Taiwan is a province of the PRC. The uncompromising messaging has continued to be seen in the PRC's statements and behaviour in almost all international venues, especially in the PRC's treaties establishing diplomatic relations with third-party countries and on Taiwan's involvement in international organizations.Footnote 46

The dual messaging has been driven by Beijing's worries that Taipei would exploit a laxer designation of “China” internationally. Chinese leaders fret that Taipei would abuse the vagueness in “one China” to assert that the island is another “China” independent from the mainland or altogether rescind its commitment to remain connected to “China,” however defined.Footnote 47 It is noteworthy that Beijing insists on dual messaging despite that its rhetoric directed towards Taiwan still negates Taipei's claim of sovereignty.Footnote 48 Therefore, Beijing's strenuous efforts to use dual expression accentuate how much China worries about the commitment problem. Beijing uses the dual messages to avoid the situation in the international community where it might find no way to put the Taiwan independence genie back in the bottle. However, for Taiwan, the dual messages exacerbate the island's misgivings about China's promises.

In Taiwan, the democratic system holds leaders accountable for the citizens’ desire to maintain and enhance their autonomy while pacifying China's demand for unification. Most people in Taiwan would prefer establishing an international personality separate from mainland China if that could be achieved peacefully. However, the bottom line for the majority is to maintain the status quo as a self-governing democracy.Footnote 49 Political parties and ruling administrations seen as caving in to China's demand and compromising Taiwan's autonomy will be punished by Taiwan's voters and lose power. For example, in the 2016 presidential and legislative elections, the KMT presidential candidate, Hung Hsiu-chu 洪秀柱, made a strategic mistake in her campaign theme, which gave voters the perception that the party's cross-Strait policy was moving away from maintaining the island's autonomy and towards unification. Consequently, voters delivered the KMT an electoral debacle that cost the party both the control of the presidential office and the legislature.Footnote 50

To improve cross-Strait relations, China insists that Taiwan at least needs to pay lip service to unification and “one China.” However, as explained earlier, Taiwan worries that “even lip services can have international political consequences – it will enhance China's case and make it even harder for Taiwan to live freely.”Footnote 51 Like China, Taiwan's concerns about the commitment problem have driven the island to engage in dual messaging.

In the 1990s, the ruling KMT regime's rhetoric towards mainland China preached a political framework that saw two “political entities” exist under “one China.” However, towards the international community, Taiwan emphasized that the two sides of the Taiwan Strait were two “sovereign states” while avoiding mentioning “one China” altogether. Taipei worried that Beijing's differentiated narratives towards Taiwan versus the international community intended to create a rhetorical trap for the island.Footnote 52 By continuing to equate the PRC to China internationally, Beijing's dual narratives would make Taiwan's commitment to “one China” look like the island had acknowledged being part of the PRC in the international system. From Beijing's perspective, Taiwan's abandonment of the claim to represent the whole of China while dodging any reference to “one China” simply lent credence to its worries that Taiwan was pursuing separation from the mainland.Footnote 53

The commitment problem and dual messaging did not abate even during periods of rapprochement. Between 2008 and 2016, the KMT and the CCP used the 1992 Consensus to circumvent the “one China” issue and initiated a détente. However, the Chinese side still resented that, regarding the 1992 Consensus, the KMT emphasized that each side had its respective interpretation of “one China,” instead of that both sides belonged to “one China.”Footnote 54

The DPP governments – the Chen Shui-bian administration in the early 2000s and the current Tsai Ing-wen administration – adopted strategies similar to the KMT's. Towards the PRC, Chen talked about a “future one China” through incremental political integration, while Tsai used the ROC constitution, which still claims mainland China as its territory, to appease the PRC's demand on committing to keep Taiwan connected with China. However, towards the international community, the DPP governments emphasized Taiwan as an independent country while avoiding terms however remotely related to the “one China” concept altogether, often including the island's official name, the Republic of China.Footnote 55 The rhetorical trap and the commitment problem that worried the KMT also concerned the DPP, if not more. For example, regarding Beijing's new definition of “one China” in 2000, Chen Shui-bian bluntly pointed to China's dual messages and feared that by accepting “one China” at the outset, Taiwan would have conceded its sovereignty before the negotiation ever began.Footnote 56

What has exacerbated the commitment problem between the DPP and the CCP is the DPP's political base of pro-independence constituencies and the party's track record of advocating Taiwan's independence. From Beijing's perspective, the DPP is thus a party with political and historical baggage.Footnote 57 As a result, when DPP took the presidential office and offered overtures compromising their previous pro-independence stands and hinting at concessions on the “one China” concept, Beijing's reaction was only suspicion. China's Taiwan policy circle interpreted such moves as simply political expediency to buy time for consolidating power and expected the DPP administrations to return to their pursuit of Taiwan independence once they secured their regime legitimacy.Footnote 58 The thinking reflected classic worries of the commitment problem.

Evidence from Taiwan's Two Administrations

The Chen Shui-bian administration: a missed opportunity

The first DPP administration came to power in Taiwan in 2000. The then president, Chen Shui-bian, tried to offer an olive branch to Beijing by showing flexibility on the DPP's stance on Taiwan's independence. However, despite Chen's overtures in his inaugural speech in May 2000, which distanced himself from pursuing de jure independence, and again in his New Year's Eve speech in that year, which proposed that Taiwan and mainland China work on future political integration, Beijing did not reciprocate Chen's goodwill and insisted that Chen commit to “one China” verbally. Amid the impasse, on 21 July 2002, when Chen assumed the DPP's chairmanship, China persuaded Nauru, one of Taiwan's remaining 28 diplomatic allies at the time, to switch diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing. One Taiwanese official told the Wall Street Journal, “they [i.e. China] responded to our goodwill with a slap in the face.”Footnote 59 The incident put an end to Chen's rapprochement attempts. During his remaining tenure, cross-Strait relations were marked by frequent hair-trigger tensions.

In his inaugural speech in May 2000, Chen Shui-bian offered overtures to Beijing through his pledge of “five nos.” Chen proclaimed that as long as China did not show an intention to use military force against Taiwan, he would not declare independence, would not change the national title, would not revise the ROC constitution to describe the cross-Strait relations as a “state-to-state” relationship, would not hold a referendum on the question of independence or unification, and would not abolish the Guidelines for National Unification and the National Unification Council that symbolized Taiwan's commitment to unification. He also stated that based on democracy and parity, the two sides could jointly deal with the question of a “future one China.”Footnote 60 Furthermore, on 31 December 2000, Chen stated in his New Year's Eve speech that “one China” had never been an issue under the ROC constitution and proposed that the two sides start with economic and cultural integration to establish trust and a new framework for political integration.Footnote 61

For Chen Shui-bian, his pledge of “five nos” and talk of a “future one China” were significant concessions to Beijing, exposing him to criticism and pushback from the DPP's base.Footnote 62 However, “five nos” and a “future one China” were hardly enough for Beijing. A Taiwanese interlocutor told this author that “China suspected the DPP on Taiwan independence; China has no trust on the DPP [because] the DPP didn't give up independence.”Footnote 63 Beijing thus wanted Chen to accept “one China” straightforwardly, or at least accept mainland China's interpretation of the 1992 Consensus that, in the Hong Kong meeting in 1992, both Taiwan and the mainland had committed to the “one-China principle” verbally, even if not in writing.

From Beijing's perspective, despite Chen's reconciliatory gestures, the DPP showed no sign of surrendering its claimed goal of Taiwan independence. The party's Taiwan independence platform remained intact. Therefore, Beijing could not identify any reasons to believe that the DPP would refrain from creeping towards Taiwan independence after Chen's initial about-turn won China's concessions and enhanced the regime's internal and external legitimacy – a quintessential commitment problem. Quite the contrary, Beijing knew that the DPP's core constituencies were composed predominantly of sinophobic supporters of Taiwan independence. China's policy circle simply regarded the new DPP regime's conciliatory attempts as a tactical gambit to help the DPP consolidate its newly gained power in Taiwan.Footnote 64 From Beijing's perspective, the DPP was, in essence, still pursuing Taiwan's separation from the mainland. Any concessions to the DPP regime would only enable it to return to the Taiwan independence cause later with a stronger position. Such developments squarely went against the CCP's interests.

For Chen Shui-bian, his administration could not accept “one China” or even the 1992 Consensus. When receiving an Asia Foundation delegation in June 2000, Chen explained that Taiwan's understanding of the 1992 Consensus was as a consensus that the two sides could reach no agreement on the meaning of “one China.” However, mainland China rejected this interpretation and insisted on its own. Beijing's “one-China principle” claimed that the ROC was a part of the PRC and, therefore, the “one China” was the PRC. In other words, Chen could not accept the 1992 Consensus because Beijing's international propaganda would make it look like Taiwan had verbally committed to “one China,” and this “China” was the PRC.Footnote 65 He asserted that Taiwan's people would not accept such a position. Chen might be willing to risk deviating from the party's base. However, he could not risk alienating the majority of Taiwan's voters.

Therefore, ostensibly, what caused the two sides to miss this opportunity for rapprochement was the quibbling over Chen's verbal commitment to “one China” and the 1992 Consensus. However, in essence, the rapprochement was impeded by both sides’ apprehension of the commitment problem. Taipei worried that Beijing would not hold up its end of the bargain and treat Taiwan as an equal once the island conceded. Chen thus wanted negotiations in parity to discuss a “future one China.” In contrast, Beijing worried that Taipei would renege on its commitment to “one China” once the mainland agreed it was an issue for negotiation. Beijing thus insisted that accepting “one China” was a precondition for any discussion. The real obstacles were each side's concerns about how the international community would perceive its case through its actions. Therefore, though one of Chen Shui-bian's conciliatory gestures was to push for resuming direct postal, business and transport links (the so-called “three links”) with China that had been severed since 1949, he insisted that Beijing could not proclaim the “three links” to be internal affairs within a country. On the China side, after both joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, Beijing announced that it welcomed Taiwan's participation in the WTO as “an independent custom area of China.” The bone of contention was thus the international standing of one's case.

In contrast, the evidence did not support the argument that the rapprochement failed to materialize because of China's security threat to Taiwan. Even before Chen's inauguration, Beijing had acknowledged that it had perceived Chen's conciliatory intention. In April 2000, the deputy director of China's Taiwan Affairs Office (TAO) stated bluntly that Taiwan's new leader had delivered peace, harmony and goodwill messages in many conciliatory talks. Similarly, despite Beijing's criticism of Chen's inaugural speech and questions on Chen's sincerity, a former Mainland Affairs Council (MAC) official under Chen acknowledged that Beijing's approach had eased significantly.Footnote 66 More importantly, both China and Taiwan successfully joined the WTO in 2001, indicating that cross-Strait relations were quite stable. Nor did evidence support an identity-led explanation. The DPP's opinion poll after Chen's inauguration in 2000 found that the share of unification supporters in the society was at 35.1 per cent, almost equal to that of independence supporters at 36.1 per cent. In 2001, after Chen's proposal of political integration, supporters of unification outnumbered supporters of independence at 42.2 to 35.1 per cent.Footnote 67 Nonetheless, such amiable identification with mainland China did not remove the cross-Strait stalemate.

The Ma Ying-jeou administration: an aborted rapprochement

Chinese scholar Jinshan Zhang summarizes the “one China” framework in terms of three components: sovereignty, territory and regime. The DPP disagrees with the CCP on all three. It argues that Taiwan is a sovereign country limited to Taiwan, the Pescadores, Quemoy and Matsu. It aspires to be a regime representing an independent Taiwan.Footnote 68 The KMT traditionally agrees with the CCP on sovereignty and territory. The overlaps provide a better starting point for the two parties’ cooperation. When the KMT returned to power in 2008, the Ma Ying-jeou administration used the ROC constitution and the 1992 Consensus to construct a common ground with the CCP on sovereignty and territory while circumventing the regime issue. Cross-Strait rapprochement materialized and advanced at a breathtaking pace during Ma's first term. Within four years, China and Taiwan signed 16 cooperative agreements. However, regarding the 1992 Consensus, the Ma administration emphasized the two sides’ different interpretations of “one China” and insisted that, for Taiwan, this “one China” meant the ROC. The interpretation highlighted the cross-Strait division on the regime question and Taiwan's international personality. It touched upon the core of the commitment problem on the “one China” issue. Eventually, the CCP's wariness that recognizing separate regimes in the “one China” framework might lead to “two Chinas” in the world resulted in the abrupt end of the rapprochement.

As one of Ma's top national security advisers stated, a critical attribute to Ma's electoral victory in 2008 was his promise to deliver international dignity that the people of Taiwan desired.Footnote 69 The Ma administration's proposal linked cross-Strait relations with Taiwan's international space. It argued that cross-Strait economic cooperation and political rapprochement would open the door to trade agreements with other countries and more international participation. Taiwanese citizens were willing to give this argument a try. For example, a MAC poll in April 2009 found that 60.3 per cent of Taiwanese respondents agreed that signing an Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA) with China would help Taiwan reach free trade agreements (FTAs) with third-party countries.Footnote 70 In July 2010, this share increased to 62.6 per cent.Footnote 71 Other progress, such as Taiwan's participation in the World Health Assembly (WHA) in May 2009, also seemed to validate the strategy.

However, Beijing's worries about the uncertain repercussions of the Ma administration's assertion of another regime drove it to put straitjackets on Taiwan's international participation. Taiwan's attendance at the WHA was based on an annual invitation that China could easily turn on and off. Down the list, Taipei's participation in the International Civil Aviation Organization and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change struggled to get China's blessing because Beijing feared that “allowing Taiwan more international space will foster a de facto separation of the two states and could complicate long-term unification efforts.”Footnote 72 Beijing also discouraged third-party countries from negotiating FTAs with the island.Footnote 73 As a result, by the end of 2013, Taiwan only added FTAs with New Zealand and Singapore that together accounted for less than 7 per cent of the island's total trade. A December 2013 MAC poll showed that only 51.6 per cent of Taiwanese agreed that signing trade agreements with the mainland would facilitate similar agreements with other countries.Footnote 74 The argument that integration with the mainland was a gateway to integrating with the world began to lose its lustre.

Meanwhile, China seemed eager to push for political negotiation when Taiwan had not seen parity in the international arena. In the 2013 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping told Ma's envoy that the cross-Strait political divide could not be passed on from generation to generation.Footnote 75 On the same occasion, Taiwan's and mainland China's top officials in charge of cross-Strait affairs, the chiefs of Taiwan's MAC and China's TAO, made their historic first meeting. The MAC minister's first ever visit to mainland China followed in February 2014. For many Taiwanese, the opportunities for expanding Taiwan's international breathing space through cross-Strait rapprochement seemed minimal, while the threat of being folded into the PRC seemed to become maximal. The Ma administration's win-win argument looked more like Taiwan's one-sided concessions when China did not hold up its end of the bargain. Those who fretted about hasty political negotiations with China joined forces with other groups dissatisfied with the Ma administration for other reasons to instigate the Sunflower Movement in March 2014 to oppose a cross-Strait trade-in-services agreement.Footnote 76 The Sunflower Movement sounded the death knell for the cross-Strait rapprochement.

As Su Chi 蘇起 contends, China's apprehension about an independent Taiwan drove Beijing to oppose the Ma administration's expression of ROC in the international community and impeded improved cross-Strait relations.Footnote 77 The commitment problem that both sides faced thus explained the abrupt termination of the cross-Strait rapprochement. In contrast, China's and Taiwan's already divergent identities did not hamper the rapprochement's initiation in 2008. Neither did they emerge only in 2014 to bring down the détente. Nor did the security threat argument explain the ebb and flow of the “one China” stalemate since the Taiwan Strait security environment remained stable during Ma's presidency.

Conclusion

Fifty years after Nixon's 1972 China visit, Taiwan's democratization has transformed the nature and dynamics of the cross-Strait “one China” issue into a commitment problem in international politics. Understanding the issue's nature helps clarify ways to maintain cross-Strait stability and explore possible solutions.

Somewhat counter-intuitively, bolstering a vibrant democracy in Taiwan, where diverse interests have transparent channels to impact cross-Strait policies, can prevent extreme policy choices and help maintain stability in the Taiwan Strait. Moreover, Taiwan's effective democracy can incentivize Beijing to offer more generous terms to ensure a cross-Strait “one China” bargain is vetted through Taiwan's political process and makes it more difficult for Taipei to renege on its end of the deal, helping alleviate Beijing's concerns of the commitment problem.Footnote 78

The apparent reason that the “one China” issue has kept the Taiwan Strait a flashpoint is Beijing's unwillingness to forgo military options so long as Taipei does not relinquish its option of Taiwan independence. China claims it cannot renounce force because, otherwise, peaceful unification will become impossible. The commitment problem dynamics help explain Beijing's rationale since renouncing force will deprive Beijing of its primary leverage to hold Taipei to its commitment. However, a similar calculation applies to Taipei as well. Taipei cannot renounce the possibility of formally declaring Taiwan an independent state because, in doing so, it will lose all leverage to deter China, in the sense that it can force China to engage in risky and costly large-scale military operations on a timetable not chosen by Beijing. In other words, asking China to renounce the use of force and Taiwan to renounce independence is akin to asking them to disarm and lose their means of last resort to protect themselves from the other side's defection. As a result, if both rivals consider their respective requests as critical preconditions to solve the “one China” issue, they should be prepared to accept some international guarantee to alleviate the severe commitment problem both will face in the reconciliation process.

Acknowledgements

This research was generously supported by the Office of Naval Research (ONR), US Department of Defense under Minerva Program grant number N00014-19-1-2474. All analysis, interpretations, mistakes and oversights are solely the responsibility of the author. The author wishes to thank Scott L. Kastner for detailed feedback on earlier versions of the paper and Noah Crafts and Tyler Quillen for helpful research assistance.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical note

Dalton LIN is an assistant professor in the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs at Georgia Institute of Technology. Before joining Georgia Tech, he was a research associate with the Princeton–Harvard China and the World Program. His recent works include “The Political Economy of China's ‘Belt and Road Initiative’” in China's Political Economy under Xi Jinping: Domestic and Global Dimensions (World Scientific Publishing, 2021) and “China's Soft Power Over Taiwan,” co-authored with Yun-han Chu, in Soft Power with Chinese Characteristics (Routledge, 2019).