Local county gazetteers (xianzhi 县志) are one of the most important sources for researchers of modern Chinese history. These documents provide evidence of historical processes of local socioeconomic structuring by recording conflicts at the micro level over a long temporal scale. Since the mid-1980s, more than two thousand county gazetteers have been published across China. With access to these data and their accompanying local evidence, scholars can delve into previously unexplored topics, such as analysing aggregated county gazetteer data to study political movements and organized violence in specific regions,Footnote 1 as well as make cross-contextual comparisons.Footnote 2 However, local gazetteers vary greatly in their quality and detail when it comes to accounts of particular political episodes. While it is widely acknowledged that the writing of contemporary history is affected by political and bureaucratic constraints,Footnote 3 there is a lack of research assessing the degree of completeness of coverage and issues of underreporting of facts surrounding political events in particular localities.

In this article, we offer a novel source for studying contemporary Chinese history and measuring data manipulation in local records: the internal-discussion drafts of county gazetteers (xianzhi pingyigao 县志评议稿). Like other official publications issued by the government, local gazetteers are evaluated by internal censors in order to determine which information can be shared or is considered appropriate to present to the public. Before being finalized, a working, internal-discussion version is circulated among local officials and designated experts. These drafts go through several rounds of review and are subject to internal discussion. Although internal-discussion records are not necessarily more honest, independent or impartial than the final published versions, editors have more latitude and are less constrained by censorship from superior Party and propaganda officials during the limited internal circulation stage when compiling materials on sensitive topics.

We were able to access the full sets of the internal-discussion gazetteers from four counties in Guangxi province. We then concentrated our case analysis on the Cultural Revolution, a decade of political turbulence that profoundly changed the entire political, economic and cultural landscape of contemporary China. Arguably the most extreme period in modern Chinese history, the Cultural Revolution involved internecine mass conflict and left deep scars on Chinese society.

Based on a comparative content analysis of Cultural Revolution records in officially published county gazetteers and the unpublished internal-discussion versions, this paper measures the degree of precision and completeness of coverage in local gazetteers. Our research finds that the issue of coverage of reported political events and conflict intensity has significantly plagued the quality of event data used to study political movements and collective violence in Communist China. Further, this study's findings demonstrate the potential for researching sensitive political events by examining their internal cultural and knowledge production. Comparing internal and published materials illuminates what state authorities have included, highlighted, omitted and distorted in the production of local histories during periods of political transition and historical memory reconstruction. While county gazetteers may have relative validity in less-censored areas, given the recent systematic scarcity of new materials and lack of access to Chinese Communist Party (CCP) archives, our textual comparison serves as a caution against the tendency to take all of the data and events reported in published county gazetteers or other open state publications at face value. It also provides insight into the internal review system of state-sponsored publications in contemporary China. Our findings underscore the need for historians and social scientists to critically examine the politics of historical knowledge and culture production under the party-state system and other autocracies. This can be done by closely examining documents from within the system, third-party evidence and oral history.

The Compilation of Local County Gazetteers

In the mid-1980s, the national government mandated the compilation and publication of local gazetteers for all cities and counties. The centre hoped to revive the tradition of local historical documentation that had begun in imperial times, presumably to construct a unified historical narrative and knowledge under state rule. While the central government's National Directorate for Local Gazetteers leads each provincial office, the local government at every level, from provincial to prefectural and county level, is responsible for the compilation of gazetteers at their respective level.Footnote 4 To coordinate and unify standards, the national directorate holds a national conference every five years to discuss and examine the new national plan for compiling local gazetteers. By the early years of this decade, almost all prefecture- and county-level jurisdictions published such annals as records of their local contemporary histories.

The major task of a local gazetteer is to collect and provide background data on the development of the locality since 1949, including statistics on its population, economy, educational system, government administration and other aspects of local history. In addition to the background data, each gazetteer has a “chronology of major events” (dashiji 大事记) at the beginning of each volume, which focuses primarily on events since 1949. These chronologies recount all notable events: political events, epidemics, health campaigns, industrial accidents, and so forth. Some local gazetteers also include a separate summary section devoted to recording the entire unfolding of political movements (for example, the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution) in detail, including how they were launched in locales, diffused across the county and eventually reached their climax. Sometimes, the summaries also provide statistics and information on the number of people persecuted, abnormal deaths and the proportion of Party members involved in the movement.

The writing and publication of local county gazetteers consists of several standardized steps.Footnote 5 First, the county government appoints an editorial committee headed by the county's Party secretary or mayor and usually designates a senior cadre from the cultural or propaganda department as editor-in-chief. To demonstrate political inclusiveness and follow the imperial tradition of respecting local gentry, or to enhance the credibility of gazetteers, editorial committees may invite non-bureaucratic specialists such as renowned local scholars or writers to serve as editors or advisers. After its formation, the committee then collects raw text materials from the county archives and other relevant departments (for example, the People's Political Consultative Conference). Each government department is required to collect and submit historical materials to the editorial committee. In addition to sources from government departments, materials drawn from the public including interviews and oral histories of key historical events are collected as supplementary material.

After finishing gathering in the raw text materials, the committee starts to write the first draft of the local gazetteer, usually beginning with an overview, a chronology of major events and a politics section. The completed first draft then goes through a first round of review, which is conducted by the direct superior authorities – the prefectural gazetteer office. After, it usually takes the editorial committee one to three years to refine and write the second draft. The completed first and second drafts are labelled as “internal-discussion versions” (pingyigao 评议稿) and have to undergo several rounds of review meetings. During these meetings, Party leaders, heads of the provincial gazetteer office, designated experts and retired senior cadres scrutinize the drafts and give their feedback for future revisions, especially on key political events and sensitive issues that occurred locally. Following the review meetings, the editorial committee revises again, finishes the draft for final review (songshengao 送审稿) and then submits it to the provincial gazetteer office for final approval. Only then is the finalized version of the county gazetteer ready for publication.

The Presentation and Censoring of Sensitive Topics

As “state archives” under the control of the party-state, there are many political constraints and extensive self-censorship behaviour involved in the editing process of county gazetteers.Footnote 6 The most authoritative and comprehensive guidelines for recording unfavourable political events were introduced in 1985, along with the well-known principle, “be rough, not detailed” (yicu buyixi 宜粗不宜细).Footnote 7 With regard to “not detailed,” the guidelines elaborate: “no individual names, no trivial details, no individual cases, no comprehensive statistical data and no investigation of individual responsibility.”Footnote 8 Another influential guiding principle from around the same time states that the presentation of “politically negative movements” and “political mistakes” of the party-state should be closely scrutinized and further discussed within the local cell of the Party organization before being published.Footnote 9

By following these two conservative guiding principles, a number of sensitive issues have been systematically avoided, particularly in politics, as many local gazetteers chose either to not report or else underreport casualties during political movements.Footnote 10 For example, Shuji Cao found that many local gazetteers systematically excluded and censored sensitive data such as the number of deaths during the Great Famine.Footnote 11 Some gazetteer editors admitted that they often worked very hard to “turn the historical facts until they [fitted] into the pattern of the 1981 ‘Resolution’.”Footnote 12 Two common strategies were followed in official publications. The first involved obscuring statistics by referring only to “large numbers” of deaths or victims, instead of providing specific numbers. The second strategy involved highlighting achievements instead of acknowledging man-made political mistakes during Mao-era political movements.Footnote 13

Despite the conservative tone of the 1985 guidelines, some gazetteers and functionaries still attempted to accurately report political errors and extreme violence in their local histories. In fact, some local gazetteers editors were intellectuals or retired cadres who had themselves been harshly persecuted or unfairly treated during those very political movements. For example, a senior editor in Guangxi stated that covering political movements using only rough details was “inappropriate,” as the practice conflicted with another significant guideline of “detailing the present and abbreviating the past” (xiangjin lüeyuan 详近略远).Footnote 14 The same editor then argued that without detailed records of recent political movements county gazetteers could not adequately document history or serve as stores of information for local cadres.

The broad latitude afforded to editors resulted in notable cross-regional variation in the reporting of political events in local gazetteers, rendering the coverage of the county gazetteers uneven and unreliable. These issues impact the reliability of event data used in studies of political movements and collective violence in two specific ways: selection bias and description bias.Footnote 15 While selection bias refers to whether all of the events that occurred in localities are properly covered, description bias concerns whether the events are reported without intentional distortion or editing. Most scholarly articles on collective action agree that these two biases are unavoidable. The question for researchers, then, is whether the data are worth analysing despite such flaws and whether the bias is small enough to mean that the data are still being properly processed.Footnote 16 Authoritarian regimes’ censorship of political events intensifies the selection and description biases that already exist widely in studies of collective action. Political pressure from superiors and review agencies is particularly instrumental when selecting and describing events originally curated by gazetteer editors.

Previous studies have examined the veracity of gazetteers using other methods. For example, Andrew Walder and Yang Su use the number of words devoted to particular political events to estimate local gazetteers’ degree of precision in covering the numbers of deaths and political victims. When studying collective violence during the Cultural Revolution, they found a positive correlation between the length of the accounts in the “Cultural Revolution” section of the gazetteers and the tendency to report deaths, injuries and victims of political persecution. However, when comparing the reported numbers of deaths and victims in county gazetteers with those from other authoritative sources published by the government immediately after 1978, they found that even provinces with the longest accounts tended to underreport the actual number of deaths and injuries by 33 to 50 per cent.Footnote 17 Martin Fromm compares local gazetteers with first-hand and oral-historical testimonials from literary and historical materials (wenshi ziliao 文史资料) and finds the coverage of sensitive political events in the published versions of local gazetteers to be “scant” and “vague.” Fromm provides a critical assessment of how the mobilization, production, circulation and publication of wenshi ziliao contributed to historical knowledge production and cultural identity building in the post-Mao era.Footnote 18

Despite efforts at reflection, many researchers still rely on the published versions of local gazetteers as primary sources for demographic, political and economic data, largely because of the difficulty accessing more credible and authoritative sources. However, there has been little research on the production and review process of county gazetteers as a historical source, and how this process is situated within its unique historical and cultural context.

Data and Method

Beginning in 2016, we started collecting the internal-discussion drafts of local county gazetteers through Kongfuzi jiushu wang 孔夫子旧书网 (Confucius old book website), the largest online trading platform for used books in China. It is extremely difficult to get full sets of these internal versions because, in most circumstances, only a single copy would have been leaked to the market, leaving the volumes incomplete. In many cases, the volumes on political events are missing, making the internal materials less valuable to our study. Typically, we had to wait ten months or so to get new internal material through the online platform. A contact, a second-hand book dealer based in Guangxi, helped us to understand and monitor the market. When any related materials appeared, the book dealer notified us and we bought them immediately.

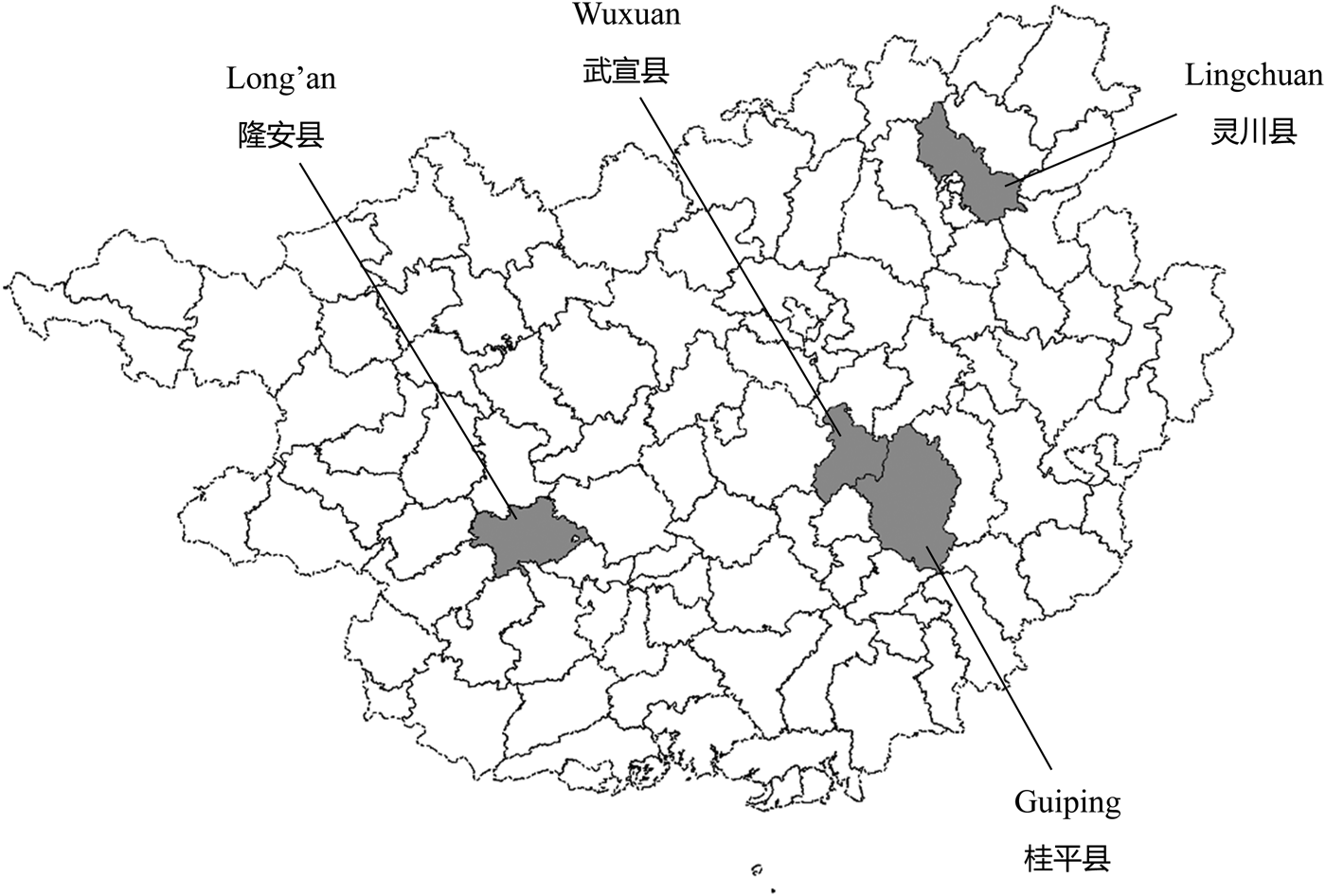

Through such efforts, we eventually collected four complete sets of internal-discussion versions of gazetteers for Guiping 桂平县, Wuxuan 武宣县, Lingchuan 灵川县 and Long'an 隆安县 counties in Guangxi province (see Figure 1). We focus our analysis on Guangxi province for three reasons. First, of all the areas that experienced terrible violence during the Cultural Revolution, Guangxi undoubtedly suffered the worst.Footnote 19 There is ample evidence of the mass killings and cannibalism that took place within Guangxi.Footnote 20 Second, following an internal investigation by the central authorities in the mid-1980s, local gazetteers in Guangxi province tended to provide more extensive accounts of political events in rural areas. We anticipate that as a result of these extensive top-down official investigations, Guangxi's internal archives would report higher magnitudes with greater reliability, in comparison to other provincial regions that did not undergo investigations of a similar scale and duration. Third, the cumulative scholarly work and smuggled secret archives concerning the Cultural Revolution in Guangxi provide opportunities to compare different types of internal materials. Such comparison not only allows for evaluating quality and reliability but also sheds light on the distinctive nature of local historical knowledge production through the gazetteer form and gazetteer office.

Figure 1. Location of the Four Counties in Guangxi Province

Each unpublished internal-discussion draft that we obtained is classified as “secret” and bears the imprint “for internal review” (neibu pinggao 内部评稿). Admittedly, these internal materials are still likely to include biases and speculative remarks. Nevertheless, given that their internal reference status means that they are not available for public view and can only be circulated among Party bureaucrats above a certain rank, they can arguably be treated as more reliable sources of information compared to most openly published documents.Footnote 21 The relative authority and reliability of unpublished internal drafts make them important sources where information is otherwise scant, especially to evaluate the validity and precision of publicly accessible documents. The value of the comparative study of internal archives and open publications has already been proven by post-1991 Soviet studies on political repressionFootnote 22 and economic planning.Footnote 23

We compared the collected internal-discussion draft gazetteers with the published editions. It should be noticed that drafts submitted for internal discussion should not be treated simply as incomplete versions of the final gazetteers; instead, they are key resources for accessing more accurate records of sensitive political events and explaining variation between districts. More broadly, investigations of the internal reviews and content revisions of gazetteers help to uncover processes of local history writing and reveal how local intellectual and cultural elites viewed the highly controversial political events, of which many of them were key witnesses and victims.

Assessing the Authenticity and Credibility of Gazetteer Writing

We conducted a close comparison of text samples extracted from two versions – the internal-discussion drafts and the final, published editions – of local gazetteers from the same county. Our analysis began by identifying the specific types of revisions made to content in the arenas of politics, culture and economy. We identified four main types of revisions that were made to the draft versions before publication: 1) revisions to statistics; 2) revisions to political events; 3) revisions to narrative perspective; and 4) revisions to less sensitive sections.

Revisions to statistics

The first category refers to the deletion or obfuscation of statistics enumerating fatalities and casualties during political events and movements, including the use of vague text descriptions instead of exact numbers. Previous studies have noted the existence of censorship on controversial and sensitive statistics, mostly related to the underreporting of deaths and casualties. With more trustworthy internal-discussion versions now available, our content analysis provides direct evidence of censorship and revisions by highlighting key differences between the two versions.

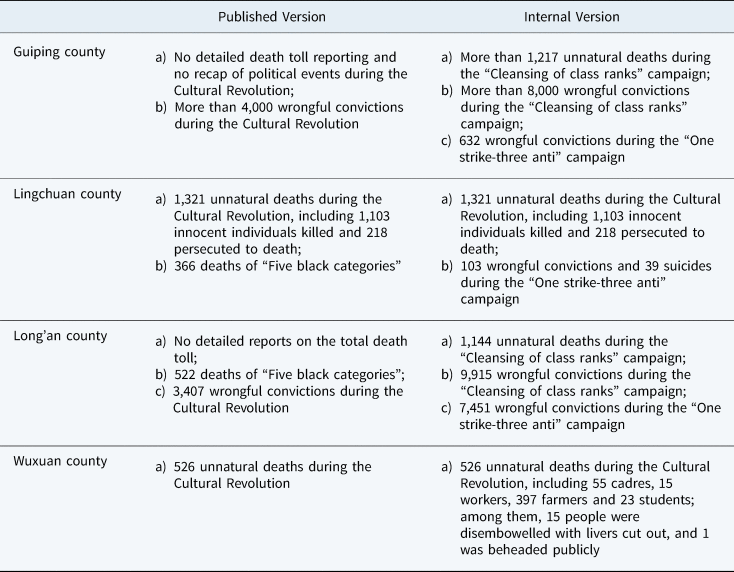

Table 1 demonstrates that the figures presented in the published versions were substantially revised, with detailed statistical reports of repressive violence during several important political events having been intentionally deleted or obscured to cover up the cruelty and tragedy of those struggles. Of the four counties, only Lingchuan reported the same number of fatalities in both versions; its internal-review version, however, contains more details on the local violence during political campaigns such as the “One strike-three anti” campaign (yida sanfan 一打三反). In Wuxuan county, the officially published version reports the same total number of deaths as the internal one, but it uses vague text descriptions instead of reporting the exact number of deaths in each social group.

Table 1. Comparing Published and Internal County Gazetteers' Statistics on the Cultural Revolution

Source: Reported statistics are cited from Guiping xianzhi 1991, 502; Lingchuan xianzhi 1997, 593; Long'an xianzhi 1993, 415; Wuxuan xianzhi 1993, 418; Guiping xianzhi pingyigao 1988, Vol. 7, 45–46; Lingchuan xianzhi pingyigao 1991, general catalogue, 41–42; Long'an xianzhi pingyigao 1988, Vol. 4, 114, 117; Wuxuan xianzhi pingyigao 1990, Vol. 6, 171.

Revisions to political events

The second category describes the truncation and deletion of sensitive passages about political events, including descriptions of factional struggles, the persecution of local intellectuals, the overthrow of local governments, military takeovers and local violence. Struggles for political power, power transitions and mass conflicts were also more susceptible to this type of revision.

In particular, we found that substantial efforts were made to censor information about three critical periods: 1) early 1967, when local rebels took power from the local government and paralysed the administration of local Party organizations; 2) late 1967, when military forces became deeply involved in the “Cleansing of class ranks” campaigns (qingli jieji duiwu 清理阶级队伍); and 3) early to mid-1968, when each locale established a revolutionary committee to re-establish order and control. The three events are widely considered to be key political junctures of the Cultural Revolution and to have triggered the most mass violence.Footnote 24

Compared to the internal draft of Wuxuan county's gazetteer, the published edition contains very little detail of the power seizure in which local militants were ordered to take over the local government and Party organs in 1967. Only the date of the revolutionary committee's founding remains. The published version also omits a description of the military's intervention in local politics. Likewise, the published version of Guiping county's gazetteer excludes the following passage regarding power seizures and the ensuing military intervention around 1967:

In January 1967, the Cultural Revolution movement reached its climax. The rebels seized the power of local Party and government agencies, as well as all enterprises and public institutions within the county. Incumbent leaders at all levels were forced to step down, resulting in the paralysis of government agencies. The county entered into a state of total anarchy.

In March, the People's Armed Forces Department of the People's Liberation Army in the county was ordered to establish the Headquarters for Organizing Revolution and Promoting Production. On 24 March 1968, with the approval of the Revolutionary Committee of Guangxi, the Guiping County Government Committee and the Party Committee were together abolished. The Guiping County Revolutionary Committee was then established to enforce unified leadership over the county's Party and government organizations.Footnote 25

Descriptions of factional conflicts and armed battles were either truncated or completely excised from the final published versions, since the violence between different rebel groups entailed the local state's loss of control and monopoly on violence. Coverage of violent activities, including factional struggles, the persecution of intellectuals and the repression of members of the losing faction, could alert readers to the violent consequences and turbulence of the Cultural Revolution. For example, Lingchuan county had the highest death toll and largest number of casualties of all the counties in Guangxi during the factional violent conflicts. When describing the intensely violent activities in its county middle school, the internal-discussion draft presented a more honest account of the fatalities and casualties and reported on the founding of Red Guard organizations within the county:

By September 1968, three middle schools established their own Red Guard organizations, which were divided into two major internal factions, one in favour of violent means (wudou 武斗) and another for civilized means (wendou 文斗). Their clash resulted in the death of 20 teachers and 22 students in these three middle schools.

Every school established the hierarchical organization of Red Little Soldiers (hongxiaobing 红小兵). By 1967, the number of Red Little Soldiers reached 20,583, and the number of instructors in the organization reached 1,057 (including 236 from outside schools). The Red Little Soldiers … were encouraged by authorities then to be anti-institution heroes (fanchaoliu yingxiong 反潮流英雄) who should frequently criticize their teachers’ teaching philosophy and personal identity.Footnote 26

These two passages were cut from the published version, however, and replaced with a single remark: “[D]uring the Cultural Revolution, the order of education was disrupted … [T]he county established the Red Little Soldier organization to replace the Young Pioneer Organization.”Footnote 27

Organized violence by the state in political campaigns is another extremely sensitive topic for the local gazetteer office to navigate. In the 1980s, even the central government still held an ambivalent view of these episodes in PRC history. An official evaluation of the Cultural Revolution referred to such events in only two sentences: the first praised the military takeover for ending the chaos, while the second characterized it vaguely as having “produced some negative consequences.”Footnote 28 Since no specific example or further explanation was offered in official documents, the best strategy for local gazetteer writers was probably to avoid writing much about controversial issues such as the repressive and brutal violence of the “Cleansing of class ranks” campaigns. For example, an entire chapter summarizing various political campaigns was deleted from the published version of the Guiping county gazetteer and the events covered in that chapter were instead mentioned in other places such as the chronology of major events.

Revisions to political content mostly focus on political power and violent factional struggles and the mass persecution carried out in local areas. The published versions also shun direct descriptions of factions involved in violent struggles, as well as the influence of provincial leadership conflicts on local rebel organizations (the pro-leadership “lianzhi faction” versus anti-leadership “4.22 faction”). In other words, revisions removed crucial information regarding the horizontal and hierarchical linkages of political movement organizations in the Cultural Revolution.

Revisions to narrative perspective

The third category refers to the manipulation and deflection of narrative perspectives on sensitive events and targets of blame. The published gazetteers present an understated picture of the degree of destruction caused by political movements in the Mao era. In addition, negative comments or criticisms targeting the Cultural Revolution as a whole (i.e. not only restricted to political content) tend to be omitted from the published versions. For example, the internal-discussion draft version of Lingchuan county's gazetteer states that “without the ten-year catastrophe wrought by the Cultural Revolution, the fiscal deposits of the county would far exceed the current number.”Footnote 29 This comment is entirely absent in the published edition.

In contrast, the published gazetteers highlight achievements in adversity and uphold a collective image of responsible local cadres who fulfilled their duties and resisted the erroneous administration of incumbent authorities. Rather than discrediting the entire movement, as some internal-discussion drafts had done, published versions place the blame on Lin Biao 林彪 and the Gang of Four for all of the country's faults, disruptions and damage. For instance, Lingchuan's internal-discussion draft blames the entire Cultural Revolution for the breakdown in school management, regular teaching, examinations and the quality of teachers, as well as the destruction of textbooks.Footnote 30 The published edition, however, places the blame on the local counter-revolutionary clique, which, allegedly following Lin Biao, rejected “the guideline and policies” for running schools that had been instituted since the founding of the PRC. Lin is also censured for instigating the Red Guard movement, although he reportedly played a less active role after its very early stages.Footnote 31

The published version of Guiping county's gazetteer also highlights another practice: the complete removal of passages related to the recruitment of Party members during the Cultural Revolution. According to the internal-discussion draft:

After the founding of the People's Republic of China, especially during the Cultural Revolution, the solicitation of Party members was disturbed by the extreme leftist ideology, which overemphasized social class and “pure” family backgrounds. Most members joining the Party were poor peasants or had a peasant family background. People from wealthier families or with slightly problematic personal histories were very likely to be refused Party membership. Only Party members raised in “poor peasant” families were considered politically reliable, but in fact their literacy and professional knowledge were generally insufficient. After the Cultural Revolution, following the instructions of the higher Party authorities, our county corrected the cursory policy used to recruit Party members and family background was no longer treated as the single most important factor for Party member eligibility.Footnote 32

Political screening during Party recruitment was deemed a persistent feature essential for the survival of the communist regime.Footnote 33 In the post-1978 reform era, although political loyalty was still a prerequisite, expertise and knowledge related to modernization and the market economy gained greater weight in the application process to join the Party. In the early 1980s, authorities openly denounced that clientelism during the Cultural Revolution had resulted from the political culture of loyally obeying one's immediate superior authorities.Footnote 34 This could explain why county gazetteers published in the mid- and late-1980s refer to Party recruitment policy during the Cultural Revolution as a “mistake.”

Openly reflecting on embarrassing histories could, however, diminish Party members’ loyalty to the regime or trigger disputes over official assessments of the Cultural Revolution – especially among those Party members who had been discriminated against because of their family class backgrounds. In contrast to Guiping county's excision, the published version of Long'an county's gazetteer retained an original passage from the draft version criticizing Party recruitment during the Cultural Revolution, blaming “some individuals from the ‘Rebel Faction,’ with clique mentality, or who favoured vandalism” for “causing the ‘impurity’ of the Party organization.”Footnote 35 Even though the published version aimed to convey the same message as the internal-discussion draft version, it still attempted to temper the tone. For example, “boluan fanzheng 拨乱反正” (correcting disorder and restoring normality) was modified to the softer and more moderate “zhengdun 整顿” (consolidation of the political order).

Revisions to less sensitive sections

Censorship strategies are more diversified and topic-specific when dealing with the less sensitive cultural sections. As with the politics sections, critical assessments of the entire Cultural Revolution and content related to political movements, especially targeting intellectuals, have been removed from the final published versions. Passages portraying the damage to various cultural areas, such as book collections, public health promotion, recreational activities, the film industry, archive management and the publishing industry, have either been truncated or removed entirely. However, education is an important exception: all four counties surprisingly present harsher criticisms in the published versions, completely denouncing the educational reforms of the Cultural Revolution.

This tendency is especially apparent in Guiping's published gazetteer, which presents detailed descriptions of the regular education system being devastated during the Cultural Revolution. It is also notable that the published version of this chapter is much longer than the original review draft. The published version blames incumbent authorities for inciting students to criticize school leaders and their teachers during the Cultural Revolution and for forcing them to perform revolutionary rituals:

In June 1966, classes were suspended for the Cultural Revolution. Primary school students were mobilized to criticize school leaders and teachers, and the Red Little Soldier organization was established to organize students stepping out into society; to break with the “four olds” [old ideas, old cultures, old habits, and old customs]; embrace the “four news” [new thoughts, new cultures, new habits, new customs]; and clean up all kinds of evil people resembling “ghosts, evils, and snakes.” After classes resumed, students were asked to follow the current political trend closely; spend a lot of time criticizing fiercely; learn from workers, peasants and military soldiers; study the spirit of the Dazhai campaign; and memorize Chairman Mao's quotations and his three classic articles.Footnote 36

Descriptions of the interruption to and chaos within education during the Cultural Revolution are extensive in the other three counties’ gazetteers as well, with the final versions usually exceeding the original length of the internal review drafts. For example, the published version of Long'an county's gazetteer includes a new passage describing how fanatical the rituals and political loyalty show had become, thus making an implicit criticism of Mao's personality cult:

From May to July 1970 … [m]ass meetings of “recalling, thinking, and checking” were launched widely across the county: first, participants had to recall the sufferings of the working class in the old society, think of the kindness of Chairman Mao, and check whether their loyalty to the regime was firm enough; second, they had to recall the history of the struggle between the two lines within the Communist Party, think of Chairman Mao's great deeds, check whether their revolutionary determination to follow Chairman Mao was abiding; third, they had to recall their own life experiences, think of their experiences doing things that complied with Chairman Mao's instructions, check whether they were loyal to Chairman Mao and Mao Zedong Thought.Footnote 37

Guiping county's final version even adds a paragraph to highlight the failures of educational reforms during the Cultural Revolution:

When the college entrance examination was restored in 1977, only 99 out of 8,013 liberal arts high school students in the county passed mathematics subjects, 98.8 per cent of them failed the exam. That year, the number of graduates admitted to colleges and technical secondary schools in Guiping ranked last in Guangxi. In the mathematics exam of the 1978 college entrance examination, 22.4 per cent of sciences high school students from our county scored 0; 66.7 per cent of liberal students scored 0 … Many middle and high school graduates were unprepared for work, given the limited education they had received. From 1979 to 1986, more than 6,000 cadres and workers of public units had to participate in catch-up literacy classes.Footnote 38

To sum up, the published versions contain extended and detailed passages on topics such as the indoctrination of extreme leftist ideology, abolishing the examination system, the introduction of physical labour into the curriculum, the mismanagement of schools by revolutionary committees, and the indiscriminate expansion of every type of school across rural areas, which had been deemed as “too aggressive” and resulted in severe teacher shortages. This editorial tendency can be attributed to the Party's rehabilitation of cultural elites in the late 1970s and the subsequent loosening of the total control over cultural affairs. The relaxation of speech and thought control to the level of the early 1950s allowed gazetteer writers to re-examine the devastation of cultural and educational activities that occurred in earlier political movements.Footnote 39

In the economy section, censorship strategies are also topic specific. While the internal-discussion drafts clearly criticize the political turbulence and a revolutionary mindset for causing unnecessary economic damage, the published versions only vaguely mention the faults of the Cultural Revolution rather than actually naming specific policies or economic ideas. In terms of economic statistics, the published versions not only omit data showing economic downturns or declines in industrial production but also manipulate statistical years to intentionally generate data indicating economic growth. Some contain new data or detail based on the review drafts, but these insertions only appear in the least politically sensitive economic topics, such as forestry management and the agricultural credit union.

Similar to the sections on politics and culture, censorship of economic subjects mainly concerns the period after military intervention in 1967. Highlighting hard-won economic achievements amid political restiveness, statistics that imply economic growth, especially in the areas of grain production and infrastructure improvements, are presented in the published versions. For example, the internal-discussion draft of Lingchuan's gazetteer reports on the economic setbacks and development during the Cultural Revolution in a mixed and impassioned manner:

After the initiation of the Cultural Revolution, economic developments in the county were interrupted, and the situation took a sharp turn. Lingchuan, like other places in China, experienced great turmoil … In 1967, under the influence of the “January Storm” of Shanghai's power seizure, the Party and government organs were seized at various levels, the economic management departments were forced to stop their activities, the effectively functioning system was abolished, anarchy was rampant and military weapons were distributed to wage a “full civil war.” As a result, in 1967 and 1968, the total output value of industry and agriculture fell sharply, fiscal revenue dropped acutely, market commodity supplies were tight, cultural and educational undertakings were devastated, and the economic order was on the verge of collapse.

The total industrial output value in 1967 was 18.7 per cent lower than in 1966, and in 1968 it was 29.9 per cent lower than in 1967; the total grain output was 7.5 per cent and 12.2 per cent lower than in 1966 and 1967 respectively. After 1969, owing to the combined effect of various factors, the social and political situation became relatively stable … However, during two political movements, “Criticize Lin Biao and Confucius” and the “General war against capitalism and revisionism,” the previous efforts at economic readjustment were regarded as right-wing leaning, and self-retained land and sideline family businesses were regarded as the “tail of capitalism.” The result brought serious consequences to economic development again, leading to economic fluctuations. The county's total industrial output value dropped by 5.6 per cent in 1975 compared to 1974, and in 1976 it dropped by 1.8 per cent compared to 1975.Footnote 40

The published version, in contrast, removes the preceding detailed passage on economic disasters from 1966 to 1976 and replaces it with a generally positive tone:

From 1966 to 1978, state investment in industrial construction increased … In the 20 years since 1958, owing to the leftist ideological guidance, the unilateral obedience of “grain as the key link” (yiliang weigang 以粮为纲) and “steel as the key link” (yigang weigang 以钢为纲) had caused the national economy to fluctuate and develop slowly. In 1978, the total industrial output value increased by 17 times compared with 1951. The average annual growth rate was 11 per cent.Footnote 41

The two versions also differ strongly in their stances towards the “Learning from Dazhai in agriculture” movement (nongye xue dazhai 农业学大寨). The most frequent edit evident in the published version is the deletion of any account recording the intensive or inhumane facets of the movement. Comparing the two versions of Lingchuan's gazetteer also provides more evidence of a divided attitude regarding the Dazhai movement. The published version first enumerates all of the infrastructure projects completed during the campaign and then attributes the increase in effective irrigation areas from 1966 to 1976 to these achievements.Footnote 42 The internal-discussion draft, in contrast, unambiguously condemns the dreadful environmental damage inflicted from the “lopsided” and impulsive infrastructure construction.Footnote 43

Gazetteer editors also downplayed the destruction of the campaigns by reversing negative appraisals. For example, an internal-discussion draft notes that, in 1968, the county government of Wuxuan sent inspection crews to each rural work team to see if any family sidelines existed, in which case villagers owning private property would be severely punished. It stressed that even the scattered fruit trees and trees beside villagers’ residences were regarded as bourgeois legal rights.Footnote 44 In contrast, the published version replaces this allegation with an account stating that excessive collectivism was moderated in each commune in Wuxuan beginning in the first half of 1971. It proceeds saying that only about a year later, all villager complaints under the jurisdiction had been resolved and discontented villagers had been pacified.Footnote 45

Discussion and Conclusion

This article has used internal-discussion versions of gazetteers as a novel source for studying Chinese political movements and local history under the communist regime after 1949. Although previous historical and social science studies have extensively used statistics and texts from published versions of the gazetteers, very few have delved into the process of material collection, gazetteer writing, the internal review process and censorship of the historical data.

Based on an analysis of a full-volume review of discussion drafts from four counties, we found a serious coverage issue and evidence of underreporting of political events in the published editions. Even less sensitive events like land occupation were likely to be omitted in the final versions. All passages related to the power struggles within grassroots party-state organizations were either shortened, rhetorically concealed or deleted altogether. The published versions also greatly downplayed the ideological and political connections between perpetrators (i.e. the local government, rebels from the winning faction and military forces) and policies in different periods of the Cultural Revolution. In contrast, our text analysis shows that insertions of new material and detail in the published versions were rare and tended to occur only in the case of chapters covering educational activities after 1949.

Moreover, we contend that referring to internal-discussion drafts assuages the problem of data availability and authenticity. Their restricted access – they are intended for internal circulation only among gazetteer editors, reviewers and Party officials above a certain ranking – offers the compilers greater latitude and freedom to report on sensitive political topics that could damage the public image and compromise the authority of local Party organizations and officials. Cross-text differences reveal the parts of local history that subnational governments have managed to repress or indeed emphasize. This helps to reconstruct a local collective memory of and response to the extreme social and political turmoil of the late Mao era.

In sum, this paper makes two key academic contributions. First, it advances the study of social movements where accessible data are currently limited. Using internal state archives and conducting a comparative content analysis allows us to examine the reliability of openly accessible materials and assess any potential reasons for discrepancies. Scholars of contentious politics and social movements in other authoritarian countries are likely to encounter similar problems of data access. Even when researchers have connections inside governments, the collection and use of state archives are subject to severe censorship and restrictions by state officials. In response, we have identified the existence of county gazetteer internal-discussion drafts from state archives and have obtained them from second-hand book dealers through an online customer-to-customer platform. Although these platforms also frequently face state pressure, many book dealers have the experience and creativity to circumvent censorship and state surveillance.

The discovery of internal review drafts to some extent also contributes to ongoing debates over “sinological garbology.”Footnote 46 We obtained these sources through archive dealers, which is a channel well-used by previous “garbology” historians. However, these materials are not at all trivial and can answer essential historiographical questions pondered by almost all China historians – that is, how to judge the credibility and validity of local gazetteers in the communist era. Also, these leaked state archives offer valuable insights for social scientists interested in understanding how knowledge and political authority are generated, monitored and disseminated through local history writings and bureaucratic structures.

The paper's second contribution is to promote the appropriate use of county gazetteers in contemporary Chinese studies. Given the increasing restrictions on access to data in public-sponsored libraries and archives within China, local gazetteers will continue to be indispensable sources for historians and social scientists who are interested in local political events as well as social and economic conditions under the communist regime. Although this paper calls into question the authenticity and credibility of published gazetteers, we do not deny their relative usefulness; instead, we encourage the use of published versions of gazetteers, albeit with some reservation and caution. In particular, scholars should consider whether the material being used might have encountered external manipulation or self-censorship while being compiled. We demonstrate that these publications tend to be less censored in the area of economic statistics and major events that occurred in the education field during the Mao era. However, even that content in the published versions provides in-depth and sometimes ample evidence of social changes, public finance, education reforms and even violence in schools, among other issues, at the county level.

Despite being the first study to use internal review drafts to examine the authenticity and credibility of gazetteers as well as to detail the review process, there are two main limitations to this study that could be resolved in future research. First, our sample only contains internal review drafts from four counties in Guangxi province. Additional samples from other provinces are needed in order to test the national representativeness of these documents. Second, additional qualitative evidence would be useful to supplement or challenge the findings of the cross-text comparison, as the self-censorship of gazetteer editors may not be directly reflected in the textual evidence.

Overall, the gazetteer format in Communist China represents the multiple traditions and characteristics of Chinese historical writing. These include its inherited imperial legacy, local gentry participation, bureaucratic interventions in historical writing, Party history, professionalization experiments, localized resource integration and the innovative practices of local offices. We thus encourage more scholarly efforts on examining the historiography and intellectual history of local gazetteer writing after 1978 through both archives and oral histories.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude for the invaluable feedback provided by two anonymous referees. We also thank Andrew Walder, Susan Whiting, Yuyu Yang, Lena Henningsen, Dayton Lekner and Madeleine Dong for their feedback on the earlier version of this paper. Additionally, we would like to extend our appreciation to Hao Chen, Yushi Chen, Yuzhe Sui and Wenjie Weng for their insightful suggestions on this paper. Any errors are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Competing interests

None.

Fei YAN is currently an associate professor of sociology at Tsinghua University and a joint fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study and the Harvard-Yenching Institute at Harvard University. He earned his PhD in sociology from the University of Oxford and completed a postdoctoral fellowship at Stanford University. His research interests include political sociology, historical sociology and Chinese societies. His work has appeared in Social Science Research, The Sociological Review, Social Movement Studies, The China Quarterly, Journal of Contemporary China, Modern China and China Information.

Tongtian XIAO is a PhD student in political science at the University of Washington with a focus on political economy and comparative politics. He is also interested in studying the history of Communist China using a multi-method approach.