This paper explores the perception and politics of air pollution in Shanghai. We present a qualitative case study based on a literature review of relevant policies and research on civil society and air pollution, in dialogue with air quality indexes and field research data. We engage with the concept of China's authoritarian environmentalism and the political context of ecological civilization. Air pollution is a public health and environmental problem for cities around the world. As most studies on air pollution in cities focus on measuring and improving air quality and/or the links to human health from quantitative and epidemiological perspectives, we contribute with a focus on the political and social aspects of this ecological concern.

In China, six pollutants (sulphur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), particulate matter ten micrometres or less (PM10), fine particulate matter (PM2.5), ozone (O3) and carbon monoxide (CO)) are currently monitored and an overall air quality index is reported.Footnote 1 Many cities have documented improvements in air quality and have developed implementation plans for the national Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan (2013) and the Three-Year Action Plan for Winning the Blue Sky War (2018–2020) (Blue Sky Plan hereafter).Footnote 2 Prior to these plans, a variety of actions, such as the “relocation of polluting industries, switching to less polluting fuels, enforcement of zoning regulations, stricter emission standards for mobile and stationary sources, better city planning, and increased investments in city infrastructure construction,” were aimed at reducing air pollution.Footnote 3

The governance approach has been described by scholars as “authoritarian environmentalism”: the state develops and implements policies without much public input, and civil society organizations (CSOs) conform to the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) agenda.Footnote 4 This type of authoritarianism is related to a high-level policy discourse known as “ecological civilization” – the CCP's push for greening the economy and raising environmental awareness among civil society.Footnote 5 In this paper, we show how CSOs involved in air pollution in Shanghai operate between the multilevel governance framework of authoritarian environmentalism and the context of ecological civilization. Although civil society power remains weak, the importance of the media and CSOs is growing as they publish pollution data online, openly “name and shame” polluters and promote mobile applications for monitoring air quality.Footnote 6 Via “ecological civilization,” the CCP has created discursive space for civil society participation in environmental action. Our field research shows that CSOs either closely follow government direction, engage in non-confrontational activities such as educating the public about recycling, and/or (in the case of some international CSOs and individuals) actively avoid interaction with the government.

Most of the study's participants, who represent urban practitioners engaged in environmental policy, suggested that air pollution in Shanghai was not viewed as a problem. A close examination of our interview transcripts reveals that their arguments were framed with a local (scale), short-term (temporal) denial of the environmental problem and an international (scale), long-term (temporal) acceptance of the environmental problem as a trade-off for economic development. After demonstrating this frame, we discuss variations in the Air Quality Index (AQI), as represented in air quality mobile applications from three sources: a Chinese CSO, a private company and an international CSO. This example and frame highlight the central role of the connection between technology, data and pollution visibility in the perception of air pollution.

While we find authoritarian environmentalism to be an important explanatory concept in understanding the environmental governance of air pollution in Shanghai, our research demonstrates a need to gain a better understanding of the role of technology when the state has control over the monitoring, data, evidence and models that feed into AQIs, which may be used in everyday mobile phone applications that display real-time air quality. Our findings suggest that future authoritarian environmentalism research would benefit from focusing on ways in which technology is used to communicate about the environment.

This case raises questions about why air pollution is not perceived to be a public problem even when it has been documented by government sources to be above national (Chinese)Footnote 7 and international (World Health Organization) limits.Footnote 8 Why do different applications present different statuses of the AQI for the same time and day? If air pollution is either not viewed as a problem or is accepted and the different applications show different AQIs, we contend that the connecting piece of this puzzle is the ecological and technological nature of air pollution. Specifically, its ambiguity-via-(in)visibility allows for divergent political narratives to take shape. Exploring this invisibility is important to gain policy insight to better communicate and take action towards improving air quality, a pressing concern for cities around the world.

Methods

This research is based on a qualitative case study of air pollution governance in Shanghai. It is part of a Leverhulme-funded, five-year, interdisciplinary urban sustainability project in which mutual collaboration and contributions among six sub-themes explore different aspects of urban sustainability. Shanghai is one of the case study cities of this project.

To ensure reliability and validity, we draw from a variety of sources: interviews, observations, policy documents and literature. Our field research entailed two separate visits to Shanghai and Beijing, totalling five weeks, in autumn 2018. The field trip began with five meetings with academics to gain on-site advice and recommendations for potential contacts. During the main field research period, we conducted 19 semi-structured interviews with 29 participants who either (1) worked as policy consultants for the Shanghai municipal government, (2) worked with international organizations, or (3) represented local CSOs. We audio-recorded and transcribed 14 of the interviews; of those, 12 were conducted in English and two were conducted in Chinese with interpreters who were also participants. During the interviews, we asked about environmental governance, policymaking and sustainable development in Shanghai. In order to address the potential bias of the interpreters, we transcribed and translated the discussions that occurred in Chinese. In addition to these meetings, we visited the Shanghai Urban Planning Exhibition Hall, observed a high-level conference coordinated by Fudan University (the “International symposium on air pollution”) and attended four English-language public events in Shanghai including an eco-design fair and a CSO event on citizen science and environmental action. In terms of our research positionality, we have “outsider” roles, and we acknowledge the language barrier limitation in collecting and interpreting the data.Footnote 9

Our field research was exploratory and we relied on chain referrals and the snowball method once in the field.Footnote 10 This is partly owing to the difficulty of conducting social science research in China,Footnote 11 but it is also a suitable approach for gaining a better understanding of the connections between participants and their policy networks.Footnote 12 Given our outsider position and limited connections and in-situ support in China, gaining access to some groups of actors, especially government actors, was a predictable challenge.Footnote 13 We therefore set a flexible recruitment scope and started with academics and international organizations in Shanghai and Beijing and then sought to reach local actors. Upon return and during our data analysis phase, we discussed our findings with Chinese interlocutors based at our university. We reviewed all of our data to locate key framings and themes. We understand a “frame” to be “an interpretation scheme that structures the meaning of reality,” and a policy frame as “an organizing principle that transforms fragmentary or incidental information into a structured and meaningful policy problem, in which a solution is implicitly or explicitly enclosed.”Footnote 14

Following a similar approach to that used by Anna Ahlers and Yongdeng Shen, we focus on a localized authoritarian environmentalism and air quality.Footnote 15 The focus on civil society actors reflects a recent shift by the CCP to offer space for civil society environmental activism, which is seen as a complement to the government's capacity for delivering environmental protection measures at local levels.Footnote 16 We find the conceptual work on authoritarian environmentalism important to understand and analyse our findings, and especially to respond to Ahlers and Shen's call for understanding the nuances of authoritarian environmentalism in local-level policymaking. Our approach also focuses on public engagement with air pollution, which addresses a research gap identified by Xiaoyue Li and Brian Tilt.Footnote 17

Air Pollution Governance in China

This section comprises four parts: a background on national-level air pollution policies; a review of the relevant literature on the concept of authoritarian environmentalism in cases of air pollution; the approaches taken by CSOs in China; and recent findings on the perceptions of air pollution.

Air pollution policy

At the national level, the main policy covering environmental issues is the 13th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development of the People's Republic of China (2016–2020). The Environmental Protection Law of the People's Republic of China (EPL hereafter) was revised in 2014 to supersede the 1989 EPL.Footnote 18 Additionally, air quality management is specifically in accordance with the Blue Sky Plan.Footnote 19

The Blue Sky Plan aims at developing a regional governance strategy to address air pollution through controlling industry (for example, switching fuels), improving green construction and green space in cities, improving transport (for example, more public transport and “clean fuel” vehicles), transitioning to clean production and the circular economy, market mechanisms (for example, polluter-pays policies), and monitoring and enforcing the 2014 revised EPL.Footnote 20 Local governments need to follow national law and should seek to strengthen departmental coordination.

The 2014 revised EPL is the strictest environmental law in the history of the People's Republic and places responsibility on local governments.Footnote 21 Bo Zhang and Cong Cao, however, have reservations about the EPL: first, other (less strict) laws might take precedence; second, because the environment is governed by several agencies, the enforcement of this law might be “fragmented”; third, the law gives citizens access to information and the ability to participate, but does not allow them to take legal action as it “fails to acknowledge citizens’ basic right to an environment fit for life”; and fourth, there may be conflicts of interest where local environmental protection bureaus (EPBs) do not have much power.Footnote 22 EPBs are under “dual leadership” – both by the local government and Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE), where local governments directly oversee the management and budget of EPBs.Footnote 23 The MEE's functions are to “draft environmental laws, conduct environmental impact assessments, and monitor and enforce nationally set emissions standards.”Footnote 24

The Blue Sky Plan mandates that by 2020 all prefectural-level, or higher, cities in China must have reduced their 2015 PM2.5 levels by at least 18 per cent, the number of days with heavily polluted air (i.e. days with PM2.5 levels above 100 μg/m3) by at least 25 per cent, and their 2015 SO2 and NO2 levels by 15 per cent.Footnote 25 However, while some Chinese cities (including Shanghai) have met those reduction targets and could improve their annual average PM2.5 levels to meet the 35 μg/m3 World Health Organization interim standard, Hao Feng contends that more than 200 Chinese cities are still unable to meet that standard, even after reducing their 2015 PM2.5 levels by 18 per cent.Footnote 26

Authoritarian environmentalism as concept and ecological civilization as context

According to Miranda Schreurs, the governance of air pollution is not simply top-down: “local and provincial governments which are at odds with Beijing's plans may try to slow, reshape or block the implementation of the central government's pollution control and climate change goals. One of China's largest governance challenges is improving implementation of policies at the local level.”Footnote 27 Further, the centralization of environmental targets made at the national level may create challenges for local governments when addressing their specific needs, for example some cities have higher levels of particulate matter, rather than the more commonly regulated SO2.Footnote 28 Identifying a single source of air pollution can be difficult and this impacts what level of government takes action: “the incentives for shirking are greater for diffuse sources of pollution, such as air pollution, which are less easily attributed to individual sources and thus offer more cover for free-riding.”Footnote 29 Genia Kostka and Jonas Nahm explain that the visibility of environmental pollution such as air pollution may positively correlate with central government involvement.Footnote 30 A governance difficulty here is the difference between political and physical boundaries: “environmental management strategies that stop at cities’ administrative boundaries are no longer effective, as epitomized by the frequent regional smogs. Officials need to identify good ways to collaborate across city and regional boundaries.”Footnote 31

Ahlers and Shen's exploratory case study of two air pollution policy measures in Hangzhou offers an example of how authoritarian environmentalism applies to air pollution policy.Footnote 32 The first policy measure focused on car ownership and traffic control, where a licence plate quota system was introduced without consultation, an implementation process which Ahlers and Shen describe as “highly exclusive and centralized.”Footnote 33 The second measure relocated or shut down industry after locals formed a “self-help organization” and protested against industrial air pollution, which prompted the local government to create a forum for dialogue between citizens and industry. The local government used the protests and national policies as leverage against the industry as “complications arose because many polluting plants were state-owned enterprises affiliated with local government agencies.”Footnote 34

An ecological modernization approach is demonstrated in policy discourse and referred to by the CCP as “ecological civilization.” It views “nature” as a part of life and promises social justice for marginalized groups – yet is purposefully distinct from Western notions of sustainability and sustainable developmentFootnote 35 and attempts to re-orient society away from the previous economic growth at-all-costs priority.Footnote 36 Mette Hansen and Zhaohui Liu characterize ecological civilization as a top-down, state-driven future imaginary, which has evolved from previous notions of “socialist civilization” and “spiritual civilization” and, as such, ecological civilization focuses on technology and science to advance Chinese society.Footnote 37 For example, the final point in the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan is in line with an ecological civilization approach. It is also the only mention of citizens, with a goal to:

Widely mobilize social participation. Everybody is responsible for environmental protection. Actively carry out various forms of communication and education to spread the scientific knowledge of the prevention and control of air pollution … advocate more civilized, energy-efficient and greener consumption living styles, guide the public to start with themselves and start from simple actions. Cultivate the behaviour principle “fight together for the same air we breathe” in the whole society.Footnote 38

This could impact public participation: “due to ecological civilization's emphasis on the need to heighten environmental consciousness and improve the environmental behaviour of all its citizens, it has also in practice opened new doors – while keeping others closed – for environmental activism.”Footnote 39 This raises questions about how civil society can participate in air pollution policy within these tensions between authoritarianism and calls for an ecological civilization.

Civil society approaches

While “non-governmental organization” (NGO) is a prevailing term elsewhere and may be used informally in China to refer to CSOs, it is not a recognized term in the Chinese legal system. From the first regulatory document following the 1982 Constitution to all subsequent legal documents to regulate civil society, CSOs in China are officially referred to as “popular organizations.”Footnote 40 Recent updates in 2019 list three types of “legally registered” popular organizations: social associations (shehui tuanti 社会团体); social service organizations (shehui fuwu jigou 社会服务机构) (formerly called civil non-enterprise units); and foundations (jijinhui 基金会).Footnote 41 All three types are required to be non-profit organizations (NPOs). Besides these official categories, other types of NPOs in China include those that are registered and operate under host state organs in relevant fields, and those registered as businesses, small community-based organizations, religious organizations or rural cooperatives.Footnote 42

In addition to managing domestic social organizations, the Law of the People's Republic of China on Administration of Activities of Overseas Nongovernmental Organizations in the Mainland of China (ONGO Law hereafter) came into force on 1 January 2017. Besides strict requirements regarding registration, this new law also requires ONGOs to submit annual plans for their activities and annual reports of their previous activities, including “audited financial report, details of activities and personnel or organizational changes.”Footnote 43 Furthermore, Chapter V of the ONGO Law is specifically dedicated to the oversight and supervision by “public security organs, relevant departments and organizations in charge of operations” of registered ONGOs.

Despite progress in developing legislation to manage NGO-styled organizations’ activities, ambiguity poses challenges for civil society actors as they try to position themselves. CSOs need to address their organizational identity as it affects the requirements and procedures for registration and operation.Footnote 44 However, this is not a straightforward task because the legal system uses unique terms to classify organizations.Footnote 45 For instance, in the ONGO Law and the draft of the new “Regulation for the registration and management of social organizations,” all regulated organizations are called “social organizations” and are required to be totally non-profit. This regulation makes it challenging for organizations such as social enterprises or hybrid organizations (i.e. running both for-profit and non-profit businesses) that provide social services.

The influential power of CSOs in China is considered to be weak.Footnote 46 CSOs come under pressure to operate within the existing institutional framework and CCP agenda.Footnote 47 Researchers note that the media can be forced to halt reporting on an environmental campaign and that activists often work for the government.Footnote 48 Patrick Schroeder finds that CSOs lobbying national or local governments for climate change advocacy face resistance from industry and that this puts them under pressure to avoid confrontation and to use soft methods instead.Footnote 49 For example, Hansen and Liu report that residents of one rural village did not initially recognize that indoor air pollution could be a health issue.Footnote 50 When the villagers did eventually protest, they represented their motivations in rational and scientific ways, and used existing government channels to communicate rather than confront. The authors find this action to be in line with ecological civilization in that it is not disruptive to society and the individual's environmental awareness is raised.

The Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE) is an example of an environmental non-profit organization that seeks to share environmental pollution information with the public and to develop accountability and transparency.Footnote 51 IPE creates visuals to communicate and link pollution data to affected locations. The IPE's work has expanded as the government has established more clauses for “open information.” For example, if a company is penalized for pollution, this information must be publicly shared online within 20 days.Footnote 52 The IPE publishes this information along with audits and explanations. Multinational corporations with international supply chains have been able to use the IPE's databases to monitor their suppliers and partners in China – these supply chains have exerted the most influence among the environmental governance actors (compared to civil society and the government).Footnote 53

In terms of its role as a CSO, IPE uses the government's legal framework and, by doing so, the organization wins the trust of the public and government. The IPE now has 1.2 million records of environmental pollution, with projects such as the Blue Map Database, a Pollution Information and Transparency Index and evaluations of green supply chains.Footnote 54 It is involved with several citizen science projects that utilize technology and social media (for instance, WeChat).

Perceptions of air pollution

At present, there is conflicting evidence as to whether civil society in China accepts that air pollution is a problem. There is some evidence that civil society is concerned about the environment in general and air pollution specifically. For example, in a survey conducted for the “Climate change in the Chinese mind report,” most of the respondents acknowledged climate change and encouraged policies to address it, supported the UN's Paris Agreement and trusted government information on climate change, and 33 per cent of respondents were most worried about air pollution of all the environmental concerns.Footnote 55 Li and Tilt's research finds that residents in Tangshan 唐山 link health and environment closely.Footnote 56 Their interviewees ranked the following in order of priority: children's health, personal health, family harmony, children's education, environmental quality, and jobs and income. Citizens across Chinese cities purchase indoor air purifiers, use mobile applications to check the AQI in real-time and use face masks. Protests that connect environmental pollution and social injustice are seen as a possible threat to the CCP.Footnote 57

On the other hand, there is evidence of the public's acceptance of environmental problems: “what is most striking to observers of the West is the wide acceptance of pollution as an inevitable consequence of intensified agricultural and industrial development.”Footnote 58 As some note, environmental pollution may be accepted owing to an overall improvement in living standards.Footnote 59 This acceptance can also be related to improvements specifically in environmental conditions. Lee Seoungho, for example, finds: “Shanghai citizens generally acknowledge that the Shanghai government has made significant progress in environmental protection.”Footnote 60 Further, Ahlers and Shen claim that government data are not questioned by the public: “air quality measurements conducted (or contracted) by superior-level evaluators are now increasingly seen as hard facts in China – notwithstanding all the whitewashing of data and the opacity that may still prevail especially vis-à-vis the public.”Footnote 61 Similarly, Hansen and Liu report that it was only after the government and media began to discuss air pollution that villagers realized that it was a problem affecting them.Footnote 62 This links to the authoritarian context where the government (and its environmental evidence) is accepted.

Another factor in the perception of air pollution in an authoritarian context is the representation of the issue by the government. Ming Liu and Yiheng Zhang conducted a corpus-assisted discourse analysis on news articles that discuss air pollution from the government-supported China Daily (a tool for the Chinese government to communicate to the world about China) compared with Anglo-American newspapers (The Guardian, The New York Times and The Times), specifically examining the “constructions of scientific (un)certainty about the health risks.”Footnote 63 The authors claim that while all papers discuss air pollution and health, the articles in the Anglo-American newspapers claim more scientific certainty. For example, China Daily might use the term “heavy” to describe smog as a way to focus on the weather condition, whereas the Anglo-American newspapers use dramatic vocabulary such as “choking,” “toxic” and “killer”: the “keyword airpocalypse even highlights China's air pollution as an apocalyptic disaster, implying that nobody in China can escape from it.”Footnote 64 China Daily would raise uncertainty about health risk claims by stating that more research and data are needed “in the Chinese context.” This technique is reinforced with claims that the causes of air pollution are complicated and multifarious. Conversely, Anglo-American newspaper articles highlight the vulnerability of air pollution victims, point to “premature” deaths (implying that the deaths are not natural) and use “scare statistics” with large numbers. Liu and Zhang's research demonstrates the importance of perception and communication regarding environmental pollution.

There are several important themes in the literature on authoritarian environmentalism and civil society in China. In terms of policy, two opposing forces appear: one is the perception of the fast pace of change in relation to a one-party system and the other is the implementation gap owing to the fragmentation of policy at different scales.Footnote 65 In terms of civil society, the push for an ecological civilization promotes citizen involvement and awareness, yet CSO power remains weak and CSOs must follow government procedures. In terms of air pollution, documented and visible improvements give an illusion of a safe level; however, air pollution levels (that are now less visible) still do not comply with national regulations and exceed World Health Organization suggested limits. It is through this conceptual lens and political context that we present findings from our case study.

Perceptions of Air Pollution and Representations of AQI in Shanghai

In this section, we discuss the identity and approach of CSOs in Shanghai, present the frame that emerged from our interview analysis, and describe one example of how technology is used to communicate about air quality.

Case study background

Shanghai is an important case given its status in China as a global city with prefecture-level governance and a comprehensive sustainability plan. Administratively, Shanghai is categorized as a province. It is a mega-city with a population of around 24 million and holds a complex position in China: it is a global city, a port city, an industrial city and plays a strategic economic role for the country. Shanghai is located on China's eastern coast, along the East China Sea and at the mouth of Asia's longest river, the Yangtze. It forms part of the Yangtze River Delta mega-city region, which is home to a population of over 50 million. The city's coastal position in the Pacific Rim once made it a strategic place for national defence; today, this location allows for economic ties nationally and internationally. The main economic sectors include service, manufacturing and finance, and the main energy source is coal.

The direct causes of air pollution in Shanghai include transport emissions, industry emissions and energy consumption. These causes are linked to economic growth, industrialization and urbanization, which result in increased vehicle use and congestion in cities.Footnote 66 Regulations were introduced to retrofit coal-fire burners, and standards were raised for vehicle emissions. As a result, in the period from 2013 to 2015, PM10 and PM2.5 decreased.Footnote 67 As coal is burned for heating, air pollution levels are seasonal, spiking during the winter season.Footnote 68 With regard to the pollutant mix, Shanghai's policy focuses more on PM than NO2 or O3. Vulnerable groups in terms of health impacts tend to be the elderly, children, females and those with low education levels.Footnote 69

Challenges for CSOs

Our field research revealed that some CSOs share the common challenge of identifying themselves as an environmental NGO. Despite the initial motivation for environmental activism, they later found it more convenient to register as private businesses or social enterprises in the environmental field (for example, as an environmental consultancy, environmentally friendly product supplier or recycling business). One interviewee noted that: “the moment you say NGO … first of all, in China you're not allowed to register yourself as an NGO … even though we used to operate as one, we are still registered as a consulting company, so, yes, being an NGO is a little harsh term.”Footnote 70

Civil society in China is often perceived as lacking in autonomy owing to the authoritarian nature of its relationship with the governmental sector.Footnote 71 This is in part a consequence of legislation – for example, the requirement of sponsorship/approval by a state organ in the registration procedure for civil society organizations. A CSO respondent remarked that “it is very difficult unless you are part of a government organization, super difficult to organize … to register as a non-profit [organization] I don't think they ever say non-governmental, it is non-profit.”Footnote 72 When asked about collaboration with state actors, this respondent shared that the relationship is “very distant, it had nothing to do with them, it had nothing to do with what we're doing … we keep our heads down, if somebody says ‘oh no don't do that,’ we say ‘OK’.”Footnote 73 In this instance, our data show that it is not always the case that CSOs’ activities are directed by state actors. Some of our respondents were non-Chinese civil society actors and, as such, their organizations and activities, although still subject to government regulations, face less pressures from the government. Despite these difficulties, civil society continues to expand in China. Two interviewees explained that this is because “[the government is] more willing to seek help from NGOs and groups,”Footnote 74 and in this way, the NGOs can “achieve [their] goals by creating a financially independent healthy relationship with government.”Footnote 75

Air pollution framing

Regardless of the affiliation of our interviewees, their overall reaction to our focus on air pollution in Shanghai was “why? It's not a problem anymore.” While the period 2010–2015 saw increased government and public action on air pollution in China, as evidenced by surveys and new and stricter regulations, our field research revealed a contradiction in the way interviewees regarded the state of the environment in Shanghai. Even though evidence shows that citizens are concerned with air pollution in Shanghai and that pollution levels often surpass legal limits, we found a clear theme among respondents, who either denied or accepted that air pollution is a problem. This theme was often placed in a frame that is both a local (scale), short-term (temporal) denial of an environmental problem and an international (scale), long-term (temporal) acceptance of the environmental problem as a trade-off for economic development. For example, one interviewee explained:

The sky was black and the local people were not satisfied with the air quality in those days, but nowadays, we can see more and more blue sky days and I think the local people … are much more satisfied with air quality compared with five years ago.Footnote 76

The frame is locally temporal in that there have been improvements to air pollution in Shanghai and thus the condition or quality of the air is compared to recent experiences of smog. This improvement merges with technology:

Over the last year, air pollution has improved a lot, you don't find people talking about it as much as they used to talk about it before. I have friends who like outdoor activities, who run a lot so their first discussion would be ‘should we go out running today? Let me check the air quality,’ but nowadays, I don't hear that so much, if people want to go out, they just go.Footnote 77

This raises a question about trusting government data more than direct, personal experience and knowledge in the absence of visible pollution. This frame links the visibility of air pollution with the ease of daily technology use to provide local environmental knowledge. According to one interviewee:

[People] go by what is told to them, so if the app says that this is beyond the limit, people start to panic generally. If there is not an app that tells you that, because you cannot see it people don't react that much … people react a lot to social media, they react a lot to what they read on the news and on chat. If they hear about a problem or scandal with a particular medicine or some food product, then they get very worried.Footnote 78

Indeed, when we asked another interviewee about the apparent smog that day, the response was “let's check the app.” Thus, this problem-denial aspect of the frame is local in spatial scale and immediate in temporal scale owing to recent improvements and the now relatively invisible quality of air pollution.

The international aspect of the frame is from an economic development perspective that a “trade-off” between economic growth and environmental protection is inevitable. For example, one interviewee explained that China is undergoing a phase of development similar to that which occurred in today's high-income countries such as the UK and US during industrialization. Environmental pollution was rationalized as a necessary function of economic development, with a much longer temporal comparison than the local environmental aspect of this frame. This interviewee continued to explain how this is related to the displacement and measurement of air pollution: the polluting industries will continue to move around China and then move to other, lesser developed, countries.Footnote 79

In terms of the international development comparison, the issue of trust in data was also apparent:

Health evidence is important for decision making but … in China, most of the environmental management decisions … rely on international evidence much more than local evidence … our central government has a close connection to the WHO, and we just use WHO guidelines as our standard, so I think it is easy for [the government] to make decisions. In the future, when the local evidence accumulates … we could have more and more local evidence about air pollution health effects. I believe that in the future, our findings are going to have implications for decision making in environmental management … the decision makers actually don't really trust local scientists; they like the studies from the US and from Europe.Footnote 80

In relation to trust, this participant also discussed the transparency of data: “in Shanghai, every company's emissions are connected to the internet and everybody can see that,” in that way “environmental data in China are very open to the public … nowadays, in terms of environmental data sharing, China is in an even better position than the US.” With increasing trust in the government's data and their acknowledgement of its progress in tackling air pollution, CSOs might be more empathetic with the government's approaches and thus focus on non-confrontational activism:

The government knows that no one likes air pollution so … it is a responsibility, but it is also a challenge and a fear … so if it wants to keep people happy, it has to [deal with the pollution] … we focus a lot of our work just on positive communication, we don't focus on the negatives. I think like every government, the Chinese government has its own set of challenges.Footnote 81

However, that trust combined with the satisfaction with the air quality status also raises a concern about losing the momentum of pro-environmental movements in China:

The challenge is how we can maintain the momentum that all of the players in the society want to have clean air as soon as possible … How they can always, no matter for government, for NGOs like us, for public, think clean air is very important for us.Footnote 82

Variations in AQI

Technology, in the form of mobile phone applications that display the AQI for a particular location, allows people to engage with the problem of air pollution.Footnote 83 The AQI is based on data from monitoring stations and conveys information about “safe” levels of overall air quality through a coded system of numerical ranges and colours: green is good (AQI of 0–50); yellow is moderate (AQI 51–100); orange is unhealthy for vulnerable groups (AQI 101–150); red is unhealthy (AQI 151–200); purple is very unhealthy (AQI 201–300); and dark red is hazardous (AQI 300 and above).Footnote 84

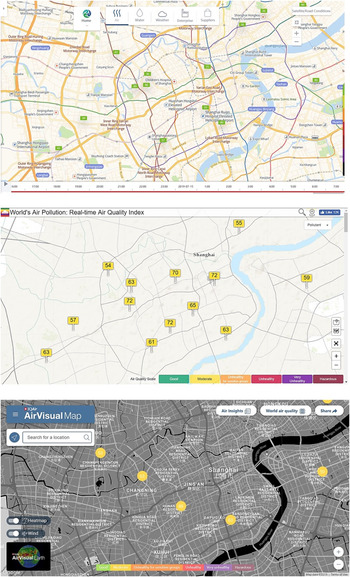

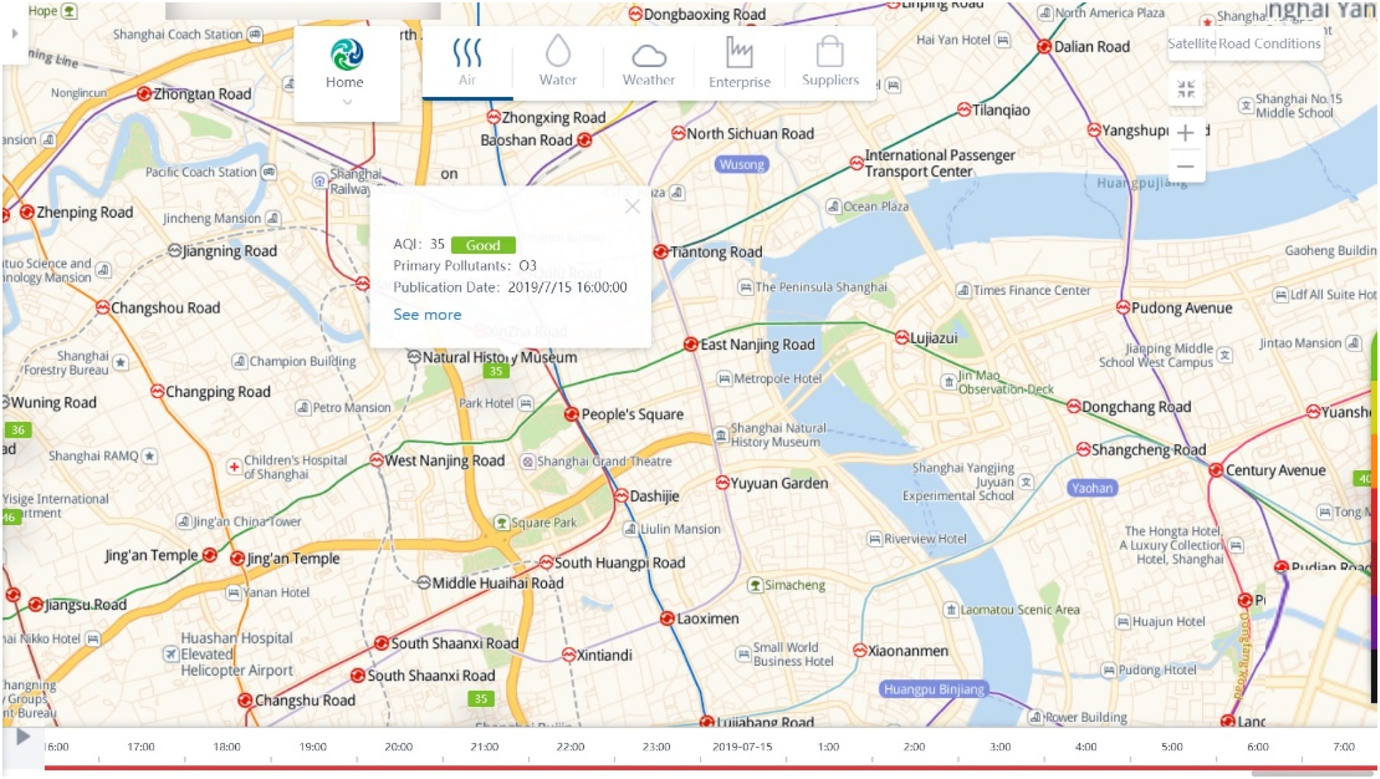

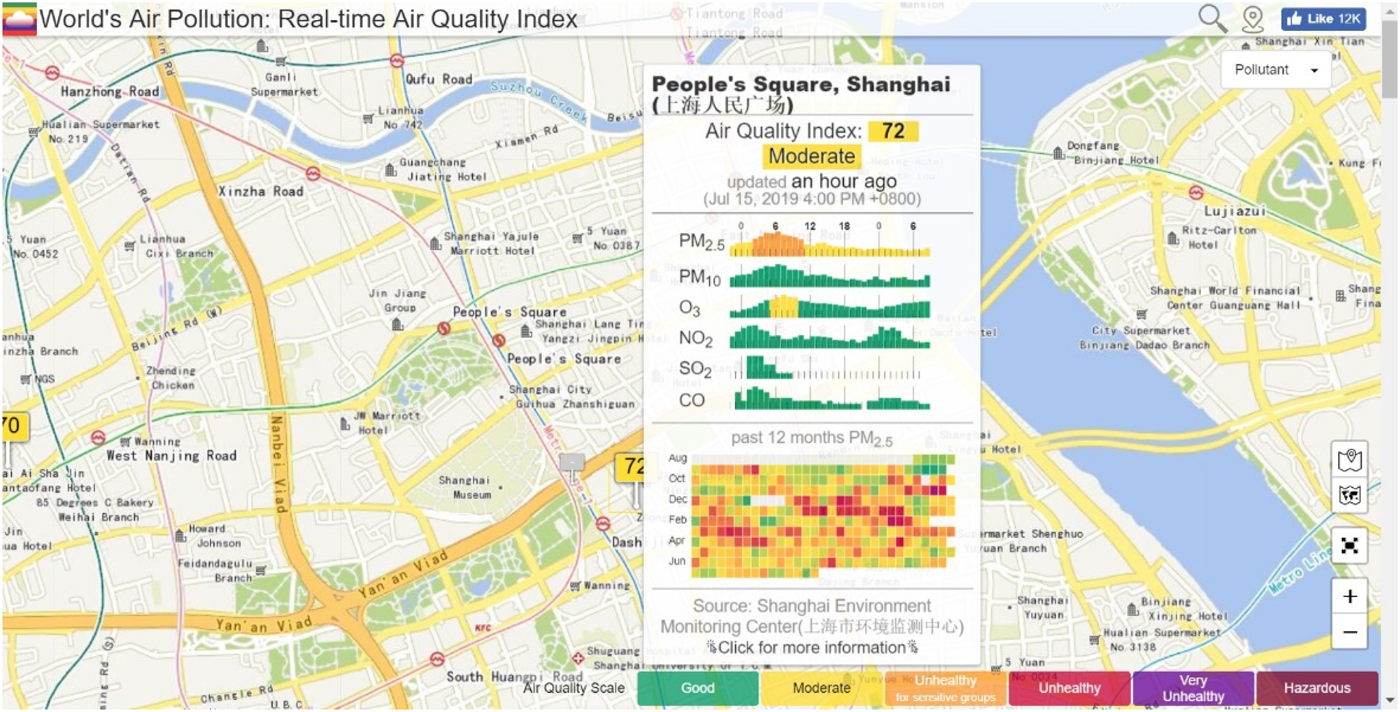

The three maps in Figure 1 (screenshots of AQIs in a central area of Shanghai published at the same time, 16:00 local time on 15 July 2019) are an example of the difference in communications about air pollution. The top map is produced by IPE and uses government data, which shows “good” air quality levels, colour-coded green. The middle map is produced by the World Air Quality Index (WAQI) Project, an international network that originated in Beijing, and shows “moderate” air quality levels in similar areas (but not always the same monitoring stations) to the IPE's map. The third map in Figure 1 is from AirVisual, which forms part of IQAir, a Swiss private company that specializes in air purifiers and air quality solutions. That map displays fewer monitoring stations but shows the highest AQI value (88) and “moderate” air quality levels.

Figure 1: A Comparison of Published Air Quality Monitoring Stations

Sources:

“Real-time maps – air quality monitoring in Shanghai.” IPE, 2019, http://wwwen.ipe.org.cn/AirMap_fxy/AirMap.html?q=1. Accessed 15 July 2019; “World's air pollution: real-time air quality index.” WAQI, 2019, https://waqi.info. Accessed 15 July 2019; “AirVisual Earth – real-time air quality map.” AirVisual, 2019, https://www.airvisual.com/earth?nav. Accessed 15 July 2019. (colour online)

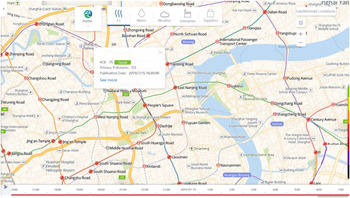

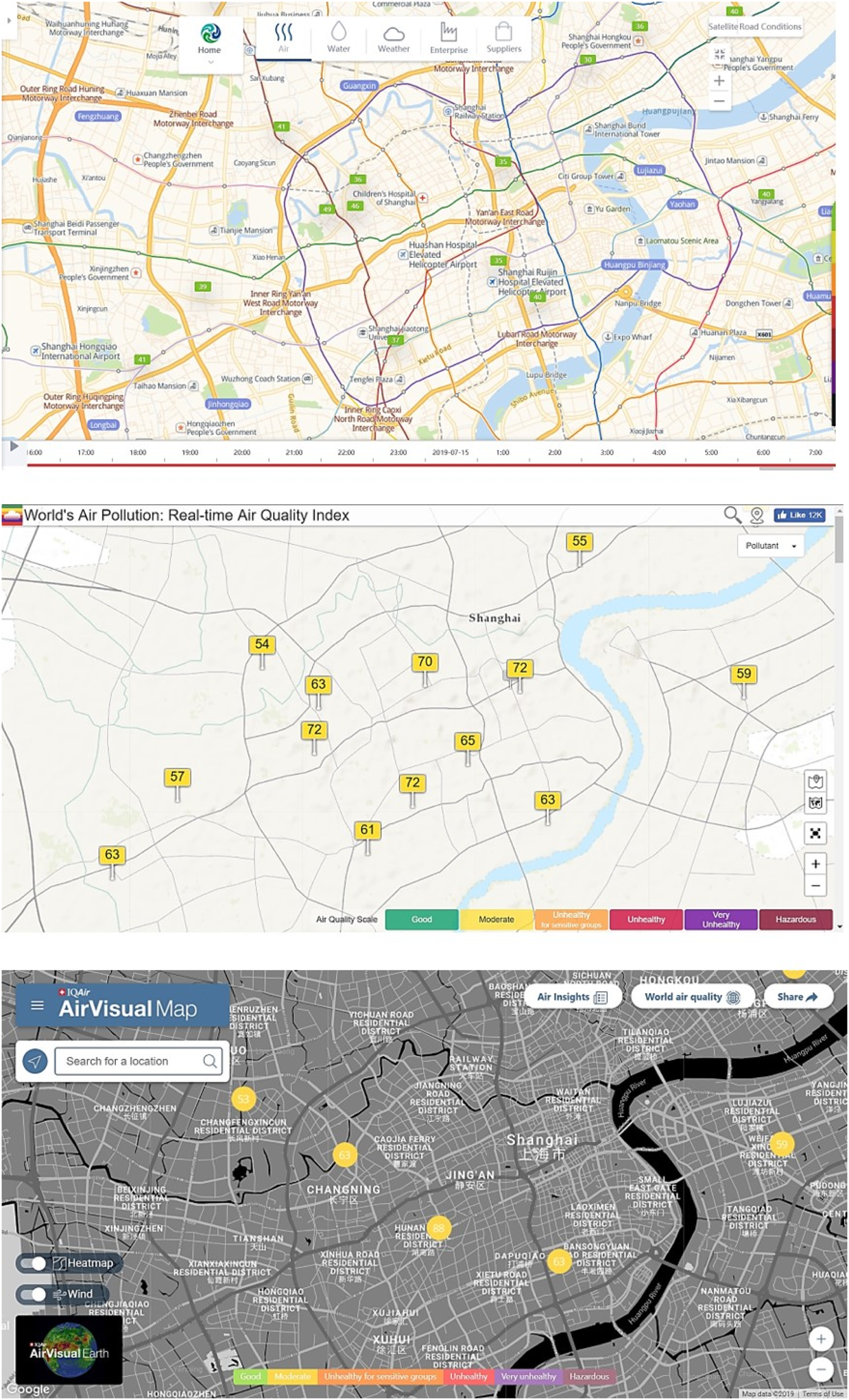

Figure 2 provides a closer look at the IPE's map on People's Square, a central area in Shanghai which is host to many daily activities, including physical exercise. The IPE's map does not show any monitoring station exclusively named People's Square, and the closest station is slightly towards the north-west. That station shows an overall good air quality index (35), with ozone as the primary pollutant. However, the WAQI's map in Figure 3 shows the air quality to be at a moderate level (72), with PM2.5 as the main pollutant. The data for the WAQI map were taken from a monitoring station located slightly south-east of the People's Square.

Figure 2: Air Quality Index Near People's Square Published by the IPE at 16:00, 15 July 2019

Source:

“Real-time maps – air quality monitoring in Shanghai.” IPE, 2019, http://wwwen.ipe.org.cn/AirMap_fxy/AirMap.html?q=1. Accessed 15 July 2019. (colour online)

Figure 3: Air Quality Index Near People's Square Published by the WAQI at 16:00, 15 July 2019

Source:

“World's air pollution: real-time air quality index.” WAQI, 2019, https://waqi.info. Accessed 15 July 2019. (colour online)

Given that both the IPE and WAQI maps claim to gather data from the government's monitoring stations, the differences could be owing to which stations are used. Furthermore, even when data are taken at the same time from the same monitoring stations, two maps may still show different values.

Our intention in highlighting the difference between these three figures is to raise questions about the technological representations and communication of air quality and to provide an example of the ambiguity that can arise, particularly with an environmental pollution that is sometimes relatively invisible. As the figures show, the different applications would provide different impressions if relied upon to determine if individual action were needed regarding air pollution that day. We are not claiming that data have been fabricated for these applications. There are a number of key factors that could influence air quality scores including the number of air quality monitoring stations and their physical placement. For example, one interviewee claimed that “part of what the central government inspections found is that in many cities, they would … put [the air pollution monitor] somewhere, you know, that was extra clear.”Footnote 85 The same interviewee expanded on what type of monitoring device can be used: “for the real-time monitoring of factories, like air and water emissions, they have a standard machine that they use … and it has to be that particular type or a similar model, so they cannot choose, and so I would assume that it is the same for governments as well, in that each of these [devices] would be a similar machine.”Footnote 86

When asked about using the government's data, one respondent from an international environmental NGO explained that the organization has “to use the data released by the government, so that the government couldn't question the basis of our analysis.”Footnote 87 This demonstrates the political aspect of authoritarian environmentalism in that CSOs feel pressure to follow government tools and technology. Another reason for this practice is the resource constraints of CSOs: monitoring air quality can be expensive, thus using government data is accessible, convenient and cost-effective.

Our findings then point to a gap in authoritarian environmentalism research, where there is a need to gain a better understanding of the role of technology within this governance context, and how it allows for communications and perceptions about the environment. The AQI examples raise concerns about trust and transparency. Further, given the growing practical interest in smart cities and the embeddedness of technology in China, they raise questions about how citizens and CSOs can use technology which has inputs and models derived from governmental sources and data. Thus, perspectives on technology as a communication tool for the CCP in the realm of environmental policy are important.

If the perception among urban sustainability practitioners is that air pollution is no longer a problem or that it is acceptable given economic growth, this perception could create significant challenges for addressing air pollution in Chinese cities in the future. The air pollution problem is now largely invisible (compared to recent visibility), yet unsafe for human health. AQI applications bring visibility to air pollution. The ambiguity created in this authoritarian context is then coupled with technology and invisibility.

A further point is that we found a lack of discussion about how ecological civilization as a CCP discourse functions in practice in combination with an authoritarian environmentalism policy approach. There is an apparent tension where participation is limited in authoritarian environmentalism, yet ecological civilization envisions more civil society participation and environmental awareness.

Conclusion

Our case study of air pollution governance in Shanghai revealed a strong theme in the discussions with our participants (urban practitioners engaged in environmental policy) about the perception of air quality in Shanghai. This was often placed in a frame that is both a local (scale), short-term (temporal) denial of an environmental problem and an international (scale), long-term (temporal) acceptance of the environmental problem as a trade-off for economic development. The improvements in air quality in recent years have translated into a perception that “air pollution is not a problem anymore.” Improvements have also been made in economic development and quality of life, which translates into a perception that air pollution is an acceptable trade-off.

AQI is a popular method to convey air quality using real-time data, environmental modelling and mapping. Citizens can use free mobile phone applications to check AQI levels. As we demonstrate, the inputs for these calculations can vary and thus the output (the index score) can vary. The context of authoritarian environmentalism and the invisible nature of air pollution then create space for those who develop AQI applications to choose the air pollution scenario and story they wish to tell. The ecological nature of contemporary air pollution in terms of the ability to physically see PM and NO2 plays a significant role in creating space for the politics of measurement and manipulation of data, creating uncertainty among the public and providing an opportunity to frame pollution as a public health or environmental policy problem. Political borders play a role in governing environmental concerns that often do not adhere to such borders. The mismatch between the administrative and ecological borders allows for politics around measuring and displacing environmental pollution.

Given the limitations of our exploratory case study in terms of language and access to data, there is a need for future research. More systematic analyses of the reporting of air pollution could use a human environment interaction approach to understand how such applications are understood and acted upon by individuals. Another area of interest would be a science and technology studies approach to further explore the role of technology in this type of authoritarian environmentalism: if technology is controlled by the government, how does technology enable citizen participation in a policy context of “ecological civilization”?

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Leverhulme Foundation under Grant No. RP 2013-SL-015.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical notes

Amanda WINTER is a postdoctoral researcher in the department of urban planning and environment's division of urban and regional studies at KTH. She is a human geographer whose interests lie in urban environmental policy and governance. Prior to joining KTH, she was a postdoctoral researcher on the “Sustaining urban habitats” project at the University of Nottingham. She completed her PhD at Central European University (Budapest), where she also taught in the “Open learning initiative for refugees” programme.

Nguyen Que Huong LE is a PhD candidate at the School of Sociology and Social Policy, University of Nottingham. Her PhD study is situated within the policy and governance theme of the Leverhulme Project “Sustaining urban habitats,” with a thesis investigating environmental governance in the context of sustainable development aspirations in Nottingham and Shanghai. Her research interests focus on human–nature interactions in various fields such as human geography, environmental sociology and sustainability governance.

Simon ROBERTS is associate professor of public and social policy at the University of Nottingham. He has designed and led numerous UK and international research projects including several national evaluations for UK government. He has worked extensively on European Commission projects including as the UK national expert on several EU networks on free movement of workers, and was a senior EU expert on the EU–China Social Security Reform Co-operation Project. He led the “Policy and governance” stream on the the Leverhulme Trust-funded study of urban sustainability, with empirical data from Nottingham and Shanghai.