Four men, in their thirties and forties, are wearing fancy dress. They pose for a group photograph, arms around each other's shoulders. The costumes, streamers, and party hats in the background suggest a celebration and, indeed, this photograph was taken at the East Berlin bar “Burgfrieden” at a Fasching, or carnival, party at the end of the 1960s (Figure 1).Footnote 1 Burgfrieden was one of the few bars where gay men could meet openly. Heino Hilger (far right), a makeup artist at the Berlin Ensemble theater, and his friends were regulars at the bar's carnival festivities. On the left is Horst Kaiser, also known as “Kaiserin,” a pharmacist, and next to Hilger is Wolfgang Lippert, or “Lippi,” who also worked at the Berliner Ensemble in the wardrobe department.Footnote 2 These three friends—and their unknown companion—were part of a gay male subculture that had developed during a period of illegality. Although arrests for homosexuality occurred only rarely in 1960s East Germany, the threat of prosecution still loomed and the subject was almost entirely taboo in the socialist public sphere. This photograph—and the others in Hilger's collection, now held in the Schwules Museum in Berlin—was taken at a time when this subculture was on the cusp of change: the government decriminalized sex between men in 1968, paving the way for significant changes in the East German gay and lesbian communities in the the 1970s and 1980s, particularly in the capital, Berlin.Footnote 3

Fig. 1. Schwules Museum, Berlin, Bestand Heino Hilger, Nr. 5, 1b.

This article takes Hilger's collection as a starting point for investigating the “queer figure” in East German photography and its relationship with the broader visual culture in East Germany and beyond.Footnote 4 “Queerness” in this context refers to the ways in which certain photographs, films, and paintings subverted and played with traditional markers of gender and sexual identity. As David Halperin has argued, “‘Queer’ acquires its meaning from its oppositional relation to the norm. Queer is by definition whatever is at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant.”Footnote 5 This article, then, is concerned not so much with homosexuality per se, but rather with the ways in which East Germans, both gay and straight, used queerness to undermine and critique existing norms of gender and sexuality.

The lack of an open public sphere in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) meant that that sort of challenge to the norm was not only potent but also particularly difficult. As several studies have shown, East German family policy and public depictions of gender were marked by a rigid heteronormativity.Footnote 6 Despite rising levels of female participation in paid employment, motherhood remained a central aspect of the representation of women's lives. New imagines of masculinity began to appear in the 1970s and 1980s, but they coexisted with the durable image of the muscular male worker. The images discussed in this article show how critique of the heterosexual norm, which originated in the semiprivate spheres of gay sociability, began to influence wider discourses about gender.

This article addresses two main questions. First, it examines the ways in which “queerness” may have been created though photography, and what it might have meant to those who appeared in, owned, and looked at the photographs. Did photography allow people to challenge gender norms? These images are significant not just as a record of the disruption of conventional binaries, but also for their performative dimension. The staging and taking of these photographs was as important to their protagonists as the events were that they portray.

The second question the article addresses is how the queer figure changed during a period when definitions and self-definitions of homosexuality were in flux. The domestic context in which gay men and lesbians shaped their identity changed significantly in the wake of the 1968 decriminalization and during the partial cultural relaxation under Erich Honecker after he assumed power in 1971. Queer cultures in the later GDR also responded to rapid international shifts in gay and lesbian self-understanding. Becoming and being queer were one way of engaging with different meanings of homosexuality, notably the tensions within the gay community between “queens” and straight-acting homosexuals. The debates sparked by such images were not confined to a gay niche. Queer oppositionality became politicized and publicized throughout the 1970s and 1980s as the queer figure began to appear in gay men's political practices, in painting and photography, in mainstream publications, and in film. As (male) homosexuality gained in visibility and public interest in the years up to 1989, elements of the subcultural photographic style in Hilger's collection found their way into the wider public sphere. The adventures of the queer figure, and reactions to it, raise questions not just about how private photography was used within subcultures, but also about how visual discourses migrate from the private sphere into mainstream visual culture.

Constructing Queer Identities through Photography

Long before the queer figure went mainstream, it could be found in collections such as Hilger's, in photographs taken in private flats and sticky, crowded bars. The exact nature of Hilger's collection is difficult to gauge. The black and white images are carefully composed, aesthetically accomplished, and taken in low light levels. Were they taken by a professional, or by an enthusiastic amateur? Their seeming spontaneity is an important part of their appeal. Yet, we need to bear in mind that this impression of spontaneity was in part a creation of the photographer. (Indeed, the color photographs in Hilger's collection, which are more straightforwardly “snapshots,” feel more awkwardly posed.) Nevertheless, while it is difficult to reconstruct the exact circumstances of their production, it is certainly possible to say something about what these photographs do—and what they may have done. On the simplest level, these photographs are a record of events. Fasching celebrations were among the high points on the gay male calendar. The photographs not only provided a memento of these red letter days, but also recorded the effort that had gone into the participants’ costumes and makeup, as well as into the decoration of the venue.

Such celebrations, and photos of them, also showcased Hilger's professional skills as a makeup artist and the ways in which he used these skills—usually acquired in the high cultural world of the Berliner Ensemble, one of the GDR's flagship theaters—in a much different subcultural space. A second set of photographs were taken in color in Lippert's flat. Figure 2 shows a group that includes Hilger (front, second from right), Fritz Schulz (“Fritzi”), a nurse, and Klaus Schmidt (“Nagelschmidti”), who worked in a hardware store. Men appear at various stages of transformation, revealing the alchemy of fancy dress and stage makeup: the queer figure in the process of creation. A magical transformation of this sort is often signaled by movement from black-and-white to color (one thinks of the movie Wizard of Oz, or of black-and-white photographs taken behind the scenes at a fashion show). Yet, in these photographs, color signals the overlit both “before” and “during” the process of transformation—black and white is the glamorous “after.”Footnote 7

Fig. 2. (Color online) Schwules Museum, Berlin, Bestand Heino Hilger, Nr. 5, 7b.

These photos not only recorded the gay subculture of East Berlin, but also helped to constitute it.Footnote 8 Taking group photographs and circulating them were part of the building of communities away from the mass organizations and official loyalties of the socialist state. The photo in Figure 1 makes clear that the act of photography itself contributed to the formation of the group. Besides the shoulder-to-shoulder solidarity and physical proximity of the four men at the center of the image, it is striking how other people are also brought into the picture—for example, the spectator on the right-hand side, standing behind the group yet also participating in the moment. Hilger, meanwhile, is making eye contact with somebody to his left, simultaneously including them in the complicity of the group, but also possibly distancing himself somewhat from the “performance” of being photographed. The gaze of the three other members of the group takes in the viewer of the photograph as well. Indeed, the semicircle in which they are standing encompasses the spectator, bringing the eye to the center of the picture.

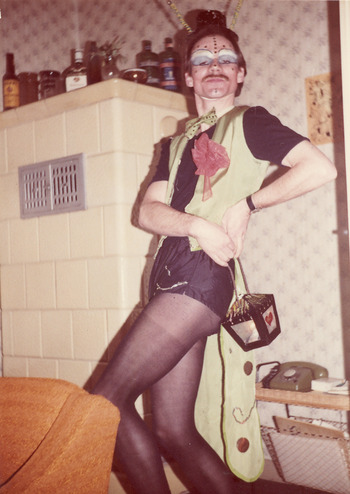

One can also see such photographs as part of the way in which individual identities—in this case, queer ones—were constituted. Another of Hilger's shots shows a man known as “Glühwürmchen” (little glow worm) getting ready for a Fasching party in Lippert's flat at the end of the 1960s (Figure 3). It offers a glimpse of how identities were created, not just by the application of makeup and the donning of a Sally Bowles-style outfit, but also by a stiff drink and the trying out of some poses in front of the camera. It is not difficult to imagine the encouraging shouts and catcalls from the rest of the party. Taking a photograph provided an opportunity to rehearse poses and pouts, to try on a different identity, and to transform one's workaday self into “Glühwürumchen” before stepping in front of the public stage. The transgressive quality of the photograph gave one permission to act outrageously, and once the evening was over, a photograph was evidence of one's queer self—proof that it had existed and would do so again.Footnote 9

Fig. 3. (Color online) Schwules Museum, Berlin, Bestand Heino Hilger, Nr. 5, 6b.

Such photographs can be seen as a record of emotional events: friendship, fun, desire, and love.Footnote 10 As Catherine Zuromskis has pointed out, popular photography and its subgenres—snapshots, portraits, photo albums—revolve around the representation of the family. But she also draws our attention to “the affective power of family photography in the construction of alternative communities and cultures”—the way in which the production and circulation of photographs offer the chance to represent and shape other types of intimacy.Footnote 11 Erika Hanna has shown how Dorothy Stokes used photo albums to capture her life as a bohemian single woman in 1920s and 1930s Ireland, at the center of a group of female friends who happily performed for the camera in a whole range of “unladylike” ways—in swimsuits, for example, and with cigarettes in their fingers. Stokes and her friends replaced the usual photographic conventions of children, weddings, and family holidays with all-female outings, silliness, and fun.Footnote 12

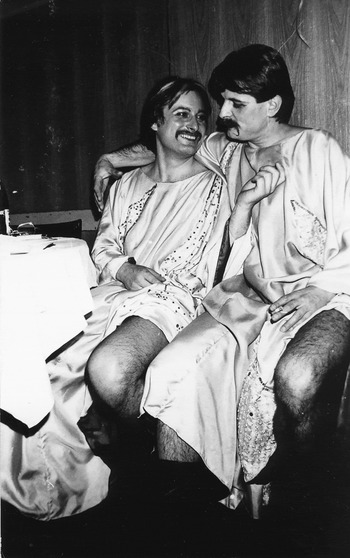

Photographs taken by Rita Thomas, known as “Tommy,” in another all-female milieu—this time in 1960s East Berlin just a mile or two from Burgfrieden—offer another example of the queer self in formation. Tommy was a dog salon owner who lived in Berlin-Friedrichshain. Her photographs show a handsome, independent woman in jeans, leather jacket, and quiff. The props in Tommy's photographs—her clothes, her motorbike, and even her prize-winning poodles—underline her self-sufficiency and unconventional lifestyle. Yet, in a subversion of the traditional couple's portrait, Tommy also posed for a studio portrait with her long-term partner and dogs (Figure 4). There is surely something queer about the way in which this photograph follows so closely the conventions of mainstream portrait photography. But its intention was arguably not satirical. Rather, it cemented a long-term relationship between two women in a society where such partnerships were completely invisible. At the same time that it subverts the traditional heterosexual portrait, this photograph may also be suggesting a more conventional view of lesbian partnerships. The photo in Figure 5, picturing a male couple in a club, the Lichtenberger Krug, in the early 1970s, captures a similar sense of intimacy between the pair. Their shared gaze, their mutual caress, the mirrored body language of their outside hands and exposed left legs: all of this creates a sense of a private moment of happiness away from the hullaballoo of the party.

Fig. 4. Schwules Museum, Berlin, Bestand Deutsche Demokratische Republik, Nr. 32, 3b.

Fig. 5. Schwules Museum, Berlin, Bestand Heino Hilger, Nr. 5, 2b.

It is tempting to see these photographs as a unique artifact from an exotic and now extinct subculture. Yet, to focus on the singularity of these images would be to overlook the ways in which they were linked to wider traditions and visual discourses, both German and non-German. Fasching is, of course, part of a long-standing tradition of carnival in Germany. Jeremy deWaal's research on Cologne shows the elasticity of the meanings of carnival.Footnote 13 Its traditions were repeatedly “reinvented”: in the medieval period it was a time of diabolic excess before Lent, but, by the nineteenth century, it had been refigured as a more wholesome battle against the forces of boredom and negativity. In the postwar period, following Nazi attempts to control carnival, Colognians reinvented it once more as a symbol of the city's tolerance and capacity for inclusion. The Fasching photographs found in numerous German photograph albums give a sense of the place of carnival in the lives of ordinary Germans. Often such photographs not only recorded the costumes, decoration, and fun, but—like carnival itself—also had a transgressive quality involving cross dressing, alcohol, or rowdy behavior. This was particularly evident in the context of the conventional family album, where they sat alongside more sedate pictures of weddings, christenings, holidays, and family gatherings.Footnote 14

A second tradition within which such photographs lie is the long-standing practice of balls and fancy dress common in gay communities elsewhere in the world. The similarities with the postwar Danish photo albums discussed by Susanne Regener are striking, in fact.Footnote 15 In the 1950s and 1960s, gay communities in both communist and capitalist societies had few opportunities to express their sexuality publicly. Dressing up, even if only for an evening with friends, harked back to the large balls and other special events that marked the gay calendar from the early twentieth century onwards, in Germany and beyond.Footnote 16 Matt Houlbrook describes the Chelsea Arts Ball and Lady Malcolm's Servants’ Ball—both held in the Royal Albert Hall in interwar London—as a transformation of “massed bodies into an unmistakable manifestation of queer urban culture.”Footnote 17 Drag and fancy dress not only stress difference, but also crucially challenge normative constructions of gender. For those who, in everyday life, may have been preoccupied with concealing their sexual identity, the ball or fancy dress party was a moment of release where invisibility became licensed visibility.

In the two decades between the legalization of homosexuality and the collapse of communism, the queer figure would find its way out of private collections and into wider East German visual culture. The two sets of photographs in Hilger's collection show the movement from a private space (Lippert's apartment) to a more public one (Burgfrieden). It is important that they were being taken at a key moment of change in the history of East German gay men, i.e., at a time when it was becoming possible for them to become more visible in public. As soon as decriminalization had lifted the threat of arrest, groups of (mostly younger) gay men began to organize events outside the traditional ghetto of gay bars such as Burgfrieden. For example, the yearly Fasching balls in the Lichtenberger Krug were a new development, a collaboration between the manager of the state-owned canteen and several gay men. Ursula Sillge remembered the compère at the Lichtenberger Krug making jokes about Honecker and barbed wire. The scene was clearly becoming bolder and also more political.Footnote 18

Queer Activism and Aesthetics

The 1970s and 1980s were also a time of increasing discussion of homosexuality in the public sphere, not least via the West German media.Footnote 19 As Jennifer Evans has shown, an international trend toward relaxation of the laws criminalizing male same-sex sexual contact meant that this was also a period in which queer figures began to become more visible in the West European and American media, too.Footnote 20 Unlike gay consumers in the West, East Germans did not have “multiple and often competing visions of queer beauty [to draw from in] their day-to-day lives.”Footnote 21 But fragments of western gay culture did make their way across the German-German border, and, as we shall see, mixed with already-existing traditions in the gay community. This resulted in a significant shift in the way in which gay men were portrayed: as the figure of the gay man became more common in visual culture, there was a growing emphasis on and interest in the representation of the kind of “queerness” and otherness that can be seen in Hilger's collection.

This was, in part, a result of deliberate political action. During the 1970s, the Berlin-based gay and lesbian group Homosexuelle Interessengemeinschaft Berlin (HIB) pursued a policy of radical gay visibility.Footnote 22 Its members were inspired by the rousing cry of Rosa von Praunheim's film Nicht der Homosexuelle ist pervers, sondern die Situation in der er lebt, (It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives) shown on West German television in the early 1970s.Footnote 23 In response to von Praunheim's slogan, “out of the toilets, onto the streets!” (Raus aus den Toilette, rein in die Straßen!) they organized outdoor seminars, impromptu participation in May Day parades, tours of the city, and hijackings of public talks. Underpinning this strategy was a conviction that gay men and lesbians should not have to hide themselves away or make themselves unobtrusive in order to be accepted by society. They shared in this common ground with the gay liberation activists of Western Europe and the United States, who also took steps to bring a more outrageous and exaggerated version of homosexuality into the public sphere.

For the HIB, photography and film were an integral part of this performative activism. Not only did the members of the HIB dress and behave in a way that was calculated to draw attention, but they were also sure to capture the moment for posterity, as well as for future consciousness-raising. In a state where the government aspired to complete control of the public sphere, their attempts at self-representation were both radical and risky. But one can again see how important photography was as a means of constituting a social and political identity. Figure 6 captures a scene from one of the HIB's regular outings, which aimed to create a feeling of gay community and “family.” The group is pictured in front of a bus, which has either just arrived or is just about to depart. This “portrait with public transport” is a motif often found in East German photograph albums, and was a common means of creating a narrative about a trip or journey. Perhaps because of the potential banality of such an image, people often struck a silly or comic pose; after all, it was hard to take oneself too seriously when standing in front of a state-owned bus.

Fig. 6. Homosexuelle Interessengemeinschaft Berlin outing. Source: Peter Rausch private collection.

Such clowning takes on a specifically and self-consciously queer dimension in this photo. While most of the people in the group are distracted or unaware that the moment for photography has arrived, the trio on the left is fully engaged with the camera. The tallest of the three gazes into the lens with exaggerated languor. The smaller standing figure closes his eyes—whether in mock ecstasy or against the glare of the sun, it is impossible to say. While these two alone would have made a touching couple, the crouching figure introduces both overt sexuality and absurdity. Like so much of the HIB's work, this photograph constituted an act of both community-building (a moment of fun and humor) and a provocation, challenging not only the heterosexual, monogamous norms of GDR society, but also the aspirations to public invisibility of an older generation of gay men.

Humor and commentary on changing sexual norms were also central to the HIB's cabaret performances. Makeup, props, and costumes were an important part of these events, picking up on older gay male traditions of drag and dressing-up. Indeed, such performances often took place as part of Fasching celebrations. One sketch for a Fasching cabaret in 1976 featured the Bitterlichs, a seemingly typical East German family of four, watching television. Everything seems conventional at first glance: father tinkering with some handicraft or other, mother sewing, daughter painting her nails. Yet, one soon notices that the son is wearing perfume, the father goes to makeup class, the daughter has been propositioned by her female math teacher, and the mother smokes cigars, watches sports, and has designs on her neighbor, Frau Kunert: “Thank goodness our family's still normal!,” Frau Bitterlich concludes.Footnote 24 This sketch's “queering” of the East German family both mocked traditional gender roles and drew attention to their instability.

The HIB's activities fizzled out towards the end of the 1970s under a heavy blanket of state obstruction. But the queer figure as an object of political discussion would live on, thanks to a younger generation of activists working under the mantle of the Protestant Church in the 1980s. Confronting what they saw as the gay community's prejudice against Tunten (queens), Ingo Kölsch and Heinrich Vogel, members of the group Gays in the Church, led performances and workshops on “Our Inner Queen” and “I'm a Queen—What are You?”Footnote 25 Their act played upon the contrast between their personal styles: Kölsch acted as the archetypal Tunte, with dyed red hair and customized clothes, while Vogel played a straight-acting blues fan who favored jeans and a parka.

Koelsch and Trummer were using queerness to raise important questions about divisions within the gay and activist scenes. It was also a good way of drawing attention to the limits of official tolerance. The government allowed a number of publications on homosexuality to appear by the 1980s, but these tended to valorize the straight-acting, monogamous gay man, while reserving their venom for the effeminate, promiscuous Tunte. As Reiner Werner put it in a book on homosexuality that appeared in East Germany in 1987: “They [Tunten] sit in cafes and smoke nonchalantly … They dance when walking and walk when dancing … Constant huffiness, petty tantrums, and childish excitement about banalities characterize their relationships.” The state's tentative steps to address homosexuality rested on unchanged assumptions about gender roles and sexual morality. Footnote 26 Placing queerness at the heart of things, as in the activism of Kölsch and Vogel, was thus a deliberate provocation.

The Fasching costumes seen in photographs from the early 1970s still draw on familiar archetypes: a Roman toga, a clown costume, a cabaret singer. But by the 1980s, queerness had moved away from “dressing-up” into stranger, increasingly countercultural territory that blurred and unsettled fixed gender categories rather than reversing them. Looking back, Kölsch drew a clear distinction between his identity as a young gay man and that of previous generations: “I wanted to be a sort of middle-being (Zwischenwesen). I was more of a punk … For me it was not about Fasching, dressing up, but sort of [being] between the sexes. But I didn't want to be a perfect copy of a woman.”Footnote 27 This creation of a gender-subversive identity was tied up with Kölsch's interest in fashion and do-it-yourself (DIY) style: his clothes were often second-hand finds that he customized and accessorized in order to make them look strange and unique. For Kölsch, queer style was not something that was only brought out for special occasions such as Fasching: it formed the basis of his everyday style. Rather than being performed two or three times a year within the gay social scene, queerness was beginning to permeate daily life and the heteronormative spaces of the GDR.

This younger generation was also creating and using new spaces, and within a decade, “queer urban culture” had transformed itself.Footnote 28 For men of Kölsch's and Vogel's age, the Burgfrieden bar was neither welcoming nor appealing. Instead, a disco in a canteen on Buschallee in Weissensee became an important site for the 1980s gay scene: “In the Buschallee [disco] you used to see more of that sort of thing, like this guy Michael whom we knew, who came out of the punk scene—no longer this ‘I look like a woman,’ but really heavy black makeup and then these colorful strands of wool, or long dreadlocks, and that sort of thing.” There was a strong sense of a mixing of different traditions and styles: the German celebrations of carnival, gay balls, and the alternative scene of the 1980s, with its DIY aesthetic and cultural appropriations. Like Kölsch, Vogel went on to underline the creativity and self-expression of 1980s queer style, contrasting it with the off-the-rack fashion of today: “People did it in private, cramped spaces, not by flicking through some magazines.”Footnote 29

Exposing the Queer Aesthetic

As queer figures came out of bars such as Burgfrieden and experimented with different elements of subcultural style, the queer aesthetic began to be adopted or appropriated by artists and photographers working within the 1980s alternative art scene. This marked an important development: these images were being created by artists and photographers who were not themselves gay, and who had, at most, experienced gay subcultures as observers. Rather than primarily constituting gay identities or subcultures, or making a political point about the inclusion of gay men and lesbians, these images used queer iconography to comment on broader issues in late state socialism.

As part of a series of work on androgyny and the body, Halle photographer Eva Mahn staged photographs of seemingly gay models wearing heavy makeup.Footnote 30 In Figure 7, the couple meets the viewer's gaze in a way that is challenging but also somewhat poignant. Their pale makeup, heavy eyebrows, and black-and-white clothes recall a Pierrot, while the smooth chest front and center of the image underscores the impression of androgyny. The photograph creates a sense of wounded defiance and dignity, of a resolution to stand together against the slings and arrows of the world. In fact, the figures in the photograph were not a couple or even gay.Footnote 31 Mahn—herself heterosexual—explained: “I found them so beautiful that I thought, if we put makeup on them, it's quite believable.”Footnote 32 This photograph alludes to the documentary tradition and to the sort of private photographs discussed earlier, but its staging owes much more to Mahn's artistic imagination than to any gay reality. For Mahn's purposes, the “authenticity” of the couple was not an issue—in fact, because much of her work explored the constructed nature of gender and sexuality, the practice of “sexual drag” may even have enhanced the appeal of these subjects. What mattered to Mahn was the beauty of her subjects, the artificiality of makeup, and the challenge to the preconceptions and prejudices of the viewer.

Fig. 7. “Rocco and Raik,” from Eva Mahn, Nichts ist mehr wie es war (Bilder 1982–1989) (Heidelberg: Braus, 1992).

Just as Mahn's photography alluded to Halle's alternative milieu, Clemens Gröszer, in his 1986 painting Café Liolet, also tried to evoke Berlin's subcultural styles and spaces (Figure 8). According to Gröszer, Café Liolet “was a legendary café in Prenzlauer Berg. I never went there myself, but painted it with my models just as I imagined it. By the mid-1980s at the latest, I consciously looked outside, tried to work against the narrowness of society, tried to free myself from it. Glimmer, glamour and triviality: I use them to ignite my art.”Footnote 33 The (imagined) color and exoticism of a lesbian café attracted this artist as an antidote to the restricted universe of the GDR, even to the point of being “outside” it and transcending it. The fact that, by the mid-1980s, a gay café could have become “legendary”—even if only within alternative circles—suggests that gay culture was resonating outside of its former confines.

Fig. 8. (Color online) Clemens Gröszer, Café Liolet, 1986. Kunstmuseum Dieselkraftwerk Cottbuss © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn.

In the painting itself, the rich red walls and tropical vegetation inside the café contrast with the looming grey building outside. Although the figure on the right is generally taken to be a woman, the size of her/his ears in particular introduces a shadow of doubt. The contrast between chalky white skin and prominent pink ears draws the eye, focusing our attention on the constructed nature of these figures’ styles and identities. Both subjects have a slightly extraterrestrial feel, with their almond eyes, glassy stares, and pointed hands. Gröszer presents queerness to us as a glamorous “other” to the tedious grey normality of East German life.

The artificiality of his queer figures is part of their appeal and part of a broader exploration within 1980s art and photography of the socialist subject as constructed and unstable. Such images constituted, in part, a critique of socialist realism's claimed authenticity, with its attempt to represent the “natural and good” order of things. Mahn was looking beyond the façade of mainstream ideas about gender, work, and parenthood. For her, as for many others, the body was a key site of identity formation and contestation. Yet, such works did not wholly reject the documentary impulse: they also sought to provide another perspective on socialism, and to shed light on marginalized and invisible social groups. And, as T.O. Immisch has shown, it was in part the official aspiration that socialist realism should include “broadness and variety” that created space for such representations.Footnote 34

It is not difficult to see why queerness appealed to alternative artists: it involved both a marginalized social group (with a pleasingly subcultural aesthetic), as well as performative subjects who were visibly in the process of constructing the self. Yet, as we have seen, both Mahn and Gröszer's queer figures were, in large part, imaginary constructions of the artistic process—with little attempt to draw on any “queer reality.” It is also striking that both images use the conventions of the couple's portrait (Gröszer's paid homage, no doubt, to the café portraits of Otto Dix), rather than posing the figures alone or in a larger group.

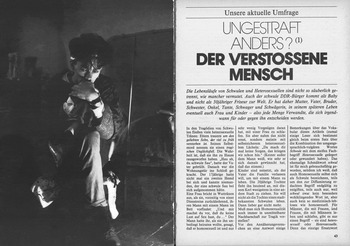

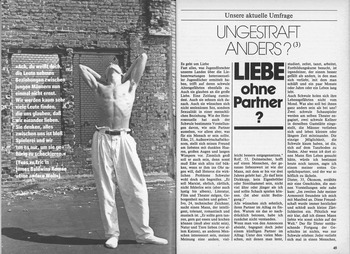

At the end of the 1980s, two cultural events in particular brought the queer subculture into the mainstream media while weaving together these activist and aesthetic strands.Footnote 35 The first was a series of three articles that appeared in 1989 in the monthly Das Magazin, which had a circulation of over 500,000. The series was significant not only because of the size of the magazine's readership, but also for its openness about the extent of homophobia in East German society. The articles moved away from the usual rhetoric that portrayed gay men as “normal,” wanting nothing more than to fit into existing structures and established roles as workers and good GDR citizens. These articles emphasized instead that to be gay was to be different—and put the onus on society to accept this. Das Magazin had always liked to see itself as a risqué publication, and acknowledging the fact that the emerging public narratives of gay life were oversimplistic offered an opportunity to break journalistic ground.Footnote 36

The way in which Das Magazin used photography to illustrate this series of three articles was extremely telling. The first article featured a photograph by Andreas Fux (Figure 9): an anguished figure sits alone in a run-down apartment, illuminated by what appears to be a television screen. This young man, who wears a headband and a bracelet, is dressed in a recognizably “alternative” style. He appears isolated, lost in thought and despair—an impression reinforced by the headline “Der verstossene Mensch (The Outcast).” The lead illustration of the second article, a photograph taken by Kurt Buchwald, foregrounds two blurry figures on a deserted, wet, dark, and wintry street (Figure 10).Footnote 37 Their features and clothing are out of focus, but at least one appears alternative—with bleached (or naturally very light) hair and a light scarf. In combination with the headline “Die versteckte Erotik (The Hidden Erotic),” the photo evokes a nighttime liaison. The illustration of the final article—another photo by Andreas Fux—also alludes to urban East German subcultures, showing a young man posing topless in front of a derelict, bricked-up building (Figure 11). As in Gröszer's painting, Fux draws a parallel between queerness and the subcultural spaces being created on the margins of GDR life. All three photographs create a feeling of tension and anticipation, a message that accorded well with the series’ depiction of a gay community awaiting a sea change in public opinion.

Fig. 9. Das Magazin, 1/1989, 42–43. Photo: Andreas Fux.

Fig. 10. Das Magazin 2/1989, 24–25. Photo: Kurt Buchwald.

Fig. 11. Das Magazin 5/1989, 44–45. Photo: Andreas Fux.

This sort of depiction of the gay body, with its clear allusions to sexual encounters and longings, marked a departure from earlier visualizations of gay men. The health magazine Deine Gesundheit (Your Health) had made homosexuality its cover story in 1978.Footnote 38 Daring and groundbreaking in its own way—this was the first time that homosexuality had been the cover story of an East German publication—the cover, which adapted the famous engraving by Albrecht Dürer of Adam and Eve to portray two men, nevertheless contained and neutralized the carnal side of sexuality in the same way as the classical nude it adapted. Das Magazin, by contrast, deliberately drew its readers’ attention to the sexual desires and frustrations of gay men.

The photographs in Das Magazin were interesting not just in their composition, but also for the choice of photographers. Fux and Buchwald were part of a much larger community of photographers: some professional, some keeping themselves afloat with other paid work, all training a critical gaze on the late GDR. Gender and the body were a common theme in their work, from the nudes of Gundula Schulze and Tina Bara to the fragmented bodies of Thomas Florschütz and Sven Marquardt's homoerotic punks. As with the work of Mahn and Gröszer, these artists drew attention to the constructed nature of sexuality and the body, and to the shortcomings of the rigid categories offered by official ideology. Using such photographs to illustrate the series made explicit the political challenge of homosexuality. For gay men to live full and happy lives, they suggested, tolerance and privacy would not suffice: what was needed was a fundamental rethinking of societal attitudes toward sex and the body.

Hot on the heels of this series in Das Magazin, the 1989 DEFA (Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft) film Coming Out also used queer figures as a foil for the conventional and officially expected life-course under state socialism. The film's main protagonist, Philipp, is the very model of the “straight-acting homosexual.” A teacher in a heterosexual relationship, but with homosexual encounters in his past, he struggles between straight respectability and gay outsiderdom. The film dramatizes this dilemma in a scene set and filmed in Burgfrieden during a Fasching celebration. Twenty years later, we find ourselves back in the world of Hilger's photographs. The camera lingers with Philipp outside on the dark street, looking longingly at the lighted and colorful window—before being abruptly tumbled through the silver door curtain into the bar. The charivari of carnival leads Philipp into a world of friendly physical contact, both platonic and sexual. Inside the bar, the artificiality of the men's costumes and makeup is juxtaposed with the authenticity of emotion they display toward Philipp and each other: fun, friendliness, generosity (Philipp is offered cigarettes and drinks), and empathy (the waiter tells him he “need not be scared”). Philipp's eyes are drawn to the outrageous and sexual nature of the carnival costumes—cross dressing, heavy makeup, exposed buttocks. Yet, the camera lingers on the visible affection and connection between the couples on the dancefloor. In an echoing of Figure 3, the viewer sees not just gay desire but intimacy as well.

Coming Out uses the queerness of Burgfrieden—and Fasching—as an example of the “otherness” and exoticism of gay life, which both repels and fascinates Philipp. Once seated at the bar, he is served by a barmaid in drag, played by Charlotte von Mahlsdorf—a well-known transvestite and, in many ways, the original East German queer figure. Mahlsdorf tells Philipp the story of trying on her first dress at the age of 15, a story that was later recounted in her post-Wende autobiography.Footnote 39 In Mahlsdorf's account, she stood in front of the mirror admiring herself when her aunt suddenly came into the room and commented, “you should have been a girl, and I should have been a man.” The film underlines this confusion and fluidity of gender when an older man crosses the dancefloor, shouting “There are no women any more, and no guys…” (Es gibt keine Weiber mehr, keine Kerle…).

The film seems to suggest that true acceptance of homosexuality involves embracing one's inner queer. Philipp's attempts to suppress his sexuality have led only to unhappiness. Yet, the film does not offer redemption through makeup and drag. Ultimately, it is Philipp's conversation with a gay but straight-acting veteran of a concentration camp that provides the pivotal scene in the film. This older, suited figure explains that he was imprisoned by the Nazis for his sexuality and only survived the camp with the help of communist fellow prisoners. Only when his own sexuality is put in the conventional political context of antifascism, and shown to be compatible with a belief in socialism, is Philipp able to come to terms with his own otherness. At the end, the film circles back to the idea that being gay involves a fundamental queerness that is incompatible with the conventionality and small-mindedness of GDR life. As the credits roll, Phillip cycles up the hill leading from the center of the city to Prenzlauer Berg, back towards the queer figures of Burgfrieden.

Coming Out returns, then, to the uneasy tension between queer and straight (and their transformation from one into the other) that was at the heart of much 1970s and 1980s gay activism. Indeed, this tension is present in Hilger's photograph collection, too. In the powerful picture taken in Burgfrieden (Figure 12), the two costumed men on the left seem absorbed in events elsewhere in the bar. The man on the right glances nervily at the camera, however. He seems both part of the masquerade—sitting in comfortable proximity to his two companions—and slightly apart from it. As in Figure 1, there is an intricate interchange among subjects, photographer, viewer, and off-camera events. This interplay between normativity and otherness, and among experience, performance, and documentation, lies at the heart of the significance of the queer figure.

Fig. 12. Schwules Museum, Berlin, Bestand Heino Hilger, Nr. 5, 3b.

Conclusion

Over the course of twenty years, the queer figure moved from the relatively hidden and little-known spaces of the gay community to the big screen and a mass-circulation monthly of the East German state. One could argue that, in some ways, it did not move very far: culturally, philosophically and geographically, this figure remained in its metropolitan niche in Prenzlauer Berg. But that assessment would not be entirely accurate. Mahn, after all, was producing and exhibiting her work in Halle, a provincial city. The “queens” of Gays in the Church took their double act on tour outside the capital. Das Magazin was a coveted consumer item throughout the GDR. And Coming Out was slated for general release—even if the opening of the Berlin Wall on the night of its premiere on November 9, 1989, stole some of its thunder.

The public discussion of homosexuality in the late 1980s certainly broke new ground, but limitations remained: it continued, for example, to focus narrowly on men. The cry of “keine Weiber mehr” in Coming Out could be seen as a rallying call for the “end of gender”—or read as a statement by a self-sufficient male subculture (and a foreshadowing of Philipp's eventual repudiation of heterosexuality). Indeed, thoughout this discussion, most queer figures were recognizably male and, at the same time, used to comment on the issues and problems of gay men. There are a number of possible explanations for this. The invisibility of lesbians (captured in the title of Ursula Sillge's semi-autobiographical Un-Sichtbare Frauen (In-Visible Women) was not unique to the GDR, but a number of factors made it especially difficult to overcome there.Footnote 40 Gay spaces that predated legalization (e.g., bars such as Burgfrieden, cruising sites) tended to be solely or predominantly male. State control of space made it almost impossible to set up women-centered alternatives. The typical East German life-course meant that many women had had children before coming out as lesbian: their domestic responsibilities consequently limited available time for socializing and political activism. The gendered nature of East German visual culture, both official and alternative, should also not be forgotten. Women were central to the GDR's self-image as independent workers and citizens, but also as objects of male desire and as mothers. The repudiation of biological destiny inherent in the “queer figure” was, if anything, more transgressive in the context of women. Just as important, subcultural artists and photographers took a keen interest in the taboos surrounding women's bodies, but their work largely focused on confronting and challenging the heterosexual viewer.

From the late 1960s, images of the queer figure played a variety of roles. First, they disrupted persistent and enduring visual norms of gender and sexuality, offering alternatives to the limited models found in mainstream socialist visual culture. Second, they had an important social function: taking, circulating, and looking at photographs and film aided in the formation of personal and group identities, helping people to develop and cement their sense of themselves and their membership in different groups. Third, such images signaled an intent to politicize and educate, both within and outside the gay and lesbian community. In the HIB's photography, in cabaret theater and filmmaking, and in Kölsch's and Vogel's interventions of the 1980s, the queer figure was used to highlight some of the hypocrisies of not only East German society, but also of the gay community itself. Fourth, the queer figure's emergence in the wider public sphere in the 1980s was a visual marker of changes in East German society and its self-understanding. By taking marginal and vilified figures as their subjects, the editors of Das Magazin and Heiner Carow, the director of Coming Out, were drawing attention to a lack of tolerance and empathy in a way that would have been impossible ten years earlier. Finally, they offered heterosexuals a glimpse into the exotic queer world, a world that was often presented as an alternative to the dull realities of daily life. The “queer” figures constructed by artists were by no means authentic, and this kind of looking was not without voyeurism.

Yet, what unites all of these images is that they were, in their own ways, intended as active interventions in—and disruptions of—the reality of GDR life. Their intentions and effects range from community building and self-invention to social critique and artistic innovation. Queer figures nevertheless provide vivid evidence of the permeability of subcultures in the GDR. Not only did queer style and iconography find its way into alternative photography and art, but a shared interest in the performative also offered a means of critiquing the rigid essentialisms of “official” views on sex, gender, and other social questions. The “glimmer, glamour and triviality” of the queer figure—its very strangeness and otherness—offered a way of asking questions about difference in GDR society. Indeed, the play between difference and sameness is central to the photographs themselves. While they mount an unmistakable challenge to heteronormativity, they also draw on mainstream genres and practices—Fasching costumes, portraiture, and family photo albums. In this way, they assert a common emotional landscape of love and friendship, loneliness and longing. In the end, these are photographs about human connections—or their absence.