Cardiac catheterisation in congenital heart disease is a developing field encompassing the foetus to the adult congenital patient. Since publication of our original training guidelines in 2010, the pendulum has swung further from diagnostic catheterisation towards increasingly complex interventional procedures.Reference Witsenburg, Qureshi, Carminati, Gewillig, Brzezinska-Rajszys and Szatmari 1 To recognise this progression, we have significantly revised and expanded our guidance for structured training in this area.Reference Duke and Qureshi 2

Furthermore, in several European nations, paediatric cardiology and, in particular, interventional cardiology are not recognised as specialty; therefore, guiding principles may be very useful.

Traditionally, cardiac catheterisation has been the definitive diagnostic investigation of choice following echocardiography in complex cases; however, in most units this is being steadily superseded by non-invasive cross-sectional imaging techniques as well as three-dimensional echocardiography.Reference Helbing, Mertens and Sieverding 3 , Reference Mertens, Helbing and Sieverding 4 In the last 10–15 years, a wide range of new equipments and procedures have been introduced in the clinical arena. The major advances have come with the development of hybrid techniques involving surgical and interventional skills.Reference Galantowicz, Cheatham and Phillips 5

This document is a revision and update of the previously published recommendations and summarises the requirements for training in diagnostic and interventional cardiac catheterisation. It does not include recommendations for invasive electrophysiology. All of the recommendations in this document must be considered in the context of local, national, and international regulations, and clinical governance structures, and are not intended to override these.

Programme structure

Programme director and faculty

There should be a designated director, or lead interventionist, in each cardiac catheterisation laboratory dedicated to training in diagnostic and therapeutic congenital catheterisation. The programme director should be a paediatric cardiologist with recognised experience in interventional congenital cardiac catheterisation, responsible for directing the procedures undertaken in the laboratory and should manage other interventional paediatric cardiologists. The faculty should be responsible for regular review of performance through clinical audit and comparison of the laboratory results with international data. They should also supervise and support quality-improvement initiatives. The programme director, as well as other faculty involved in cardiac catheterisation, should keep up to date with the latest technology and state-of-the-art diagnostic and interventional techniques. They should be responsible for the review and introduction of new techniques, radiation safety, and the clinical administration of the laboratory.

The medical faculty working in the paediatric cardiac catheterisation laboratory should be trained and experienced in techniques used in paediatric cardiology and in the care of infants and children. The non-medical staff working in the cardiac catheterisation laboratory, such as nurses, cardiac physiologists, and radiographers, should also be trained accordingly. Catheterisation of adults with congenital heart disease should be performed by teams trained in the investigation and treatment of congenital heart disease in all age groups.Reference Singh, Horlick, Osten and Benson 6 The training provided in the unit and therefore the accredited skill set acquired by the trainee should be determined by the mix of paediatric and adult congenital cases handled by the institution.

Facilities and equipment

A training institution should have a catheterisation laboratory equipped in accordance with the recommendations of the Association for European Paediatric Cardiology.Reference Brzezinska-Rajszys, Carminati and Qureshi 7 – Reference Jacobs, Babb, Hirshfeld and DR 9 Because of technological improvements, some modifications and updates should be taken into consideration, and these are noted below.

Setting and facilities

Training in diagnostic and interventional catheterisation in congenital heart disease should occur in an institution with paediatric cardiology inpatient and outpatient facilities, paediatric intensive care, paediatric anesthesiology, and a paediatric cardiac surgical programme. The cardiac catheterisation laboratory should be available 24 hours a day for emergency procedures. It should be located near the cardiac operating rooms. The presence of an adult congenital cardiology and cardiac surgical programme in the institution will bring an added value to the training programme. The training programme must have regular teaching sessions in which diagnostic data and therapeutic outcomes are presented and discussed. There should be a regular morbidity and mortality meeting, with active contribution of the trainees, and participation of the cardiology staff, cardiac surgeons, intensivists, and anaesthetists.Reference Abu-Zidan and Premadasa 10 The institution should have strong links to or be part of an academic or university facility.

The catheterisation laboratory should have adequate space to enable conversion into an emergency surgical theatre. A sterile environment should be maintained in the catheterisation room, comparable to that expected in the operating room. Ideally, there should be an induction room for anaesthesia, and adequate space for the control room, storage facilities, and space dedicated to reviewing and reporting examinations.

Hybrid procedures are increasingly being used in congenital heart disease, and hybrid suites are of exceptional value in a training programme. Although the use of portable equipment in a large operating room, which is able to accommodate the necessary staff and equipment, is an alternative approach, it is still not ideal.Reference Bonatti, Vassiliades and Nifong 11 Recommendations regarding imaging quality and processing should be implemented in the operating room with special attention paid to radiation exposure and protection in this setting.

Other imaging techniques, such as transthoracic and transoesophageal echo, should be available within the catheterisation laboratory. Computerised tomography and magnetic resonance imaging should be available within the institution to allow for a comprehensive approach to case planning and management of congenital heart disease.

Equipment

The minimum fluoroscopic requirements are single plane, flat panel digital systems, but ideally there should be biplane digital systems and rotational angiography. The equipment must generate high-resolution digital images and provide online instantaneous replay of angiograms. It should enable measurements of cardiac and vascular structures, as well as “road-mapping” for interventions. High-quality imaging must be ensured by regular servicing and upgrading of the system.Reference Brzezinska-Rajszys, Carminati and Qureshi 7

There must be standard protocols concerning measurement of radiation exposure and to ensure maximum protection against radiation for patients and staff. The “As Low As Reasonably Achievable” principle for radiation usage should be applied. Measurement and recording of fluoroscopy times and total radiation dose should be carried out routinely.Reference Justino 12

The laboratory must have high-quality monitoring and recording equipment for continuous electrocardiography, non-invasive and invasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry, capnometry, and temperature. There should be adequate facilities and equipment for anaesthesia. Equipment for resuscitation should be available within the catheterisation room and checked regularly.

It is essential to have echocardiographic equipment available, with transthoracic and transoesophageal probes for use in different age groups. This should be available for elective use and for emergencies. Availability of equipment for intravascular ultrasound and intracardiac echocardiography is highly recommended.

A large inventory of equipment specific for paediatric and adult patients with congenital heart disease should be available in the catheterisation laboratory, including sheaths, guide-wires, catheters, balloons, devices, and stents. Equipment for use in the event of complications such as pericardiocentesis kits, snares, baskets, and forceps should be available, as well as an appropriate range of covered stents, in case of vessel dissection or rupture. The precise inventory should be determined by the patient population and case mix, and be under the clinical administration of the lead interventionist.

Training programme curriculum

Prerequisite training for interventional congenital cardiology

As a prerequisite to training in interventional congenital catheterisation, the trainee should have the knowledge of and experience in paediatric cardiology, general paediatrics, and acute subspecialties including neonatology.

Early experience and training in interventional catheterisation may take place in parallel with core training in paediatric and congenital cardiology; indeed, such exposure should form an important part of the core training curriculum. Understanding the concepts involved in catheterisation, indications, interpretation of data, and the overall place of interventional catheterisation in patient management is key to becoming a congenital cardiologist. Expansion of this knowledge to include acquisition of basic technical skills of catheter manipulation and device use will be appropriate for some but not all trainees, depending on their career direction. A substantial portion of the early catheterisation experience should focus on the accurate acquisition and interpretation of haemodynamic data.

The expanding applications of interventional catheterisation in adult congenital cardiology necessitate a working knowledge of this area, and should feature in core training. Outpatient and inpatient adult congenital heart disease experience should be evidenced in the trainee’s portfolio.

Any programme that purports to train paediatric interventionists must ensure assessment of the three domains of knowledge, skills, and attitudes.Reference Dedy, Bonrath, Zevin and Grantcharov 13 – Reference Dunn and Musolino 15 The candidate’s knowledge of interventional techniques, the evidence base, and the theoretical concepts in interventional practice; their practical skills to allow the safe actualisation of these techniques; and their ethical and moral attitudes towards concepts such as informed consent, research, and fair distribution of resources should be constantly developed. Assessment of these three domains may require very different methods. It is important to recognise that, with some trainees, their greatest challenge may not lie in the practical skills required to perform an interventional procedure, but with their attitude towards communication and leadership – key features of an effective interventional clinician.Reference Dedy, Bonrath, Zevin and Grantcharov 13 , Reference Wang, Schembri and Hall 16

The training programme can be structured in three levels: basic (Level 1), intermediate (Level 2), and advanced (Level 3). The trainee’s educational supervisor or departmental mentor must set overall learning objectives for the trainee in each part of their training (Levels 1, 2, and 3). Apart from this, more focused, short-term learning objectives must be appropriately assessed through the variety of summative and formative structures detailed in the text.Reference Cotta, Costa and Mendonça 17 – Reference Bindal, Goodyear, Bindal and Wall 19

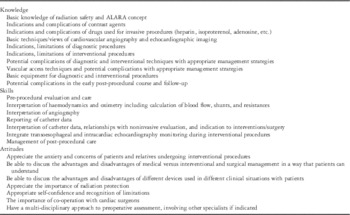

Before moving on to higher levels of interventional training (Levels 2 and 3), the trainee must have achieved the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to allow them to practice as a paediatric congenital cardiologist. These are outlined in Table 1 along with suggested methods for assessment.

Table 1 Basic training level.

ALARA=as low as reasonably achievable

Basic level

The basic level is recommended for all paediatric cardiology trainees. The goal of such training is to provide basic knowledge of haemodynamics, angiography, radiation safety, indications, risks, and benefits of interventional procedures in children and adult congenital patients.

Such core training should involve each trainee in a minimum of 50 diagnostic and interventional cardiac catheterisations. In addition, the trainee should be involved in some emergency procedures – at least five balloon septostomies and two pericardiocentesis.

Intermediate level

Training to an intermediate level will equip a paediatric cardiologist with the skills to perform diagnostic cardiac catheterisation independently and a limited range of simpler interventional procedures such as balloon pulmonary and aortic valvoplasty in older children and occlusion of uncomplicated patent arterial ducts (Table 2). Many interventional procedures have a diagnostic component as well, and the trainees should be competent in collecting and interpreting the diagnostic components in the context of the intervention being performed. The trainee should also perform ~100 interventional procedures in neonates, children, and adults, of which 50 should be as a first operator, under direct supervision. These interventional procedures should display a variety of skills and techniques across the relevant age range for the individual trainee and the training institution.

Table 2 Intermediate training level.

Advanced level

Training at the advanced level will enable a paediatric cardiologist to perform majority of the interventional procedures, requiring a high level of skill. This level can only be obtained following completion of the normal paediatric cardiology training and basic and intermediate-level catheterisation competencies. This will require continuous exposure to a wide variety of disease types and interventions for several years (Table 3). The advanced-level training should preferably be undertaken during at least 12 months of a dedicated catheterisation training programme in a high-volume teaching institution, as described above.

Table 3 Advanced training level.

By the end of this programme, the trainee should be able to independently perform the procedures listed in Table 2 (intermediate level) and under supervision procedures listed in Table 3, such as angioplasty and stenting of aortic coarctation (and recoarctation) and branch pulmonary arteries, a variety of embolisation procedures and retrieval of devices or foreign bodies. More complex procedure listed in Table 3 will need to be performed in collaboration with an expert.

The trainee should perform ~150 interventional procedures in neonates, children, and adults, of which 75 should be as first operator. Furthermore, advanced trainees need to be certified as competent by their trainers on the basis of ongoing performance of complex procedures. The level and scope of training should be clearly communicated between the trainee and the trainer during and at the completion of their training programme.

Training conduct and assessment

Conduct of training

Before any involvement in the catheterisation laboratory, the trainee should acquire the basic knowledge reported in Table 1. All trainees must attend a regular cardiologic/surgical conference, in which the indications for diagnostic and interventional catheterisation are discussed in context with history, physical examination, and non-invasive findings. Moreover, the risks, benefits, advantages, and disadvantages of interventional versus surgical procedures should be discussed in each case.

The trainee should participate in the activity of the catheterisation laboratory as follows:

Pre-procedural evaluation

The trainee is expected to assess appropriateness and to plan the strategy of the procedure by reviewing the patients’ medical record, obtaining history, and physical examination. The trainee should review all of the patients’ relevant imaging including previous catheterisation data. Blood and other laboratory examinations should be conducted and reviewed as per local protocols. The trainee’s preliminary case plan and the strategy should then be discussed with the consultant interventionist before the procedure.

The trainee should attend the interview to obtain informed consent from the patient or their parents. At the advanced level of training, she/he should obtain the informed consent for most procedures.

Performance of the procedure

The trainee must begin in mostly an observational role, initially gaining an understanding of the basic operation of physiological recorders used in haemodynamic assessment as well as the principles of fluoroscopy and angiography.

Thereafter, they should be progressively integrated into the laboratory team and environment, becoming familiar with patient postioning, equipment preparation and setting up the aseptic scrub table. Direct involvement in the procedure itself should be progressive, guided by competence and stage in training.

Post-procedural evaluation

The trainee must be involved in the critical review of case strategy, collation, and discussion of haemodynamics and angiographic data, and care of the patient after the procedure. Monitoring for post-procedural complications and discharge planning should be coordinated by the trainee in and discussed with the consultant interventionist. There should be an opportunity for regular informal debriefing with the trainer assuming a mentorship role.

Assessment

Rigorous formative and summative assessment should form part of the training programme. Apart from maintaining standards, assessment adds to the teaching and learning experience of the trainee and the trainer.Reference Wang, Schembri and Hall 16 Objective evidence of the acquisition of appropriate knowledge, skills, and attitudes must be available for a trainee to justify their completion of each of the three training levels.Reference Manthey and Fitch 14

Comprehensive, enhanced logbook

The logbook should remain a central piece of evidence of training; however, it should be more than just a list of the procedures performed. An example of a structured procedure log is shown in Table 4. The logbook should provide evidence of development through the phases of interventional training and should include:

Table 4 Example of a section of a trainees structured case diary.

This includes useful details for both the trainer and the trainee and should highlight which cases have been selected for thoughtful reflection by the trainee

(a) A list of cases performed with relevant details: This allows critical discussion between the trainee and the trainer and will help to identify the strengths and weaknesses in their progress. Linking some interesting cases to reflective summaries shows evidence of deeper thinking beyond the technical skills required in the catheterisation laboratory.Reference Cotta, Costa and Mendonça 17

(b) Reflective summaries: The trainee should be encouraged to actively reflect on their learning experiences by discussing difficult cases, complaints, and complications with their trainer and recording these in their logbook. These reflections are normally short paragraphs that conclude with an action plan or key learning point.Reference Dunn and Musolino 15

(c) Multi Source Feedback: Apart from informal feedback from other staff and clinicians regarding the trainee’s progress, a formal record of the wider team’s perception of the trainee can provide useful evidence of problems and illustrate areas that require development. Along with reflective summaries, Multi Source Feedbacks are useful ways of assessing the attitudes domain. They usually take the form of anonymised structured questionnaires, which can be distributed throughout the team, collected, and collated before feeding back the results to the trainee.Reference Egbe and Baker 18

(d) Direct Observation of Practical Skills: All trainees will, of course, be under the direct scrutiny of their trainers during cases in the catheterisation laboratory and this will provide ongoing assessment and improvement of the trainee’s skills. An overview of the efficacy of this teaching can be usefully documented with regular Direct Observation of Practical Skills assessments (Fig 1). These structured observations allow a longitudinal view of the trainee’s progress as time passes. They also allow for criteria referenced evidence of competency in key procedures for levels 1, 2, and 3.Reference Bindal, Goodyear, Bindal and Wall 19

Figure 1 Direct observation of practical skills form for use to assess procedural planning and skills in the congenital cardiac catheterisation laboratory.

(e) Personal Development Plan and notes of regular meetings with the trainer: At an early stage in training, the trainer and the trainee should be encouraged to develop a Personal Development Plan for the trainee. This should include short-term and medium-term goals and take into account the trainees extracurricular, personal, and family goals. The Personal Development Plan should be reviewed at regular meetings during the training. Furthermore, there should be a yearly review or appraisal meeting between the trainer and trainee, which may be used to generate a summary report for the local statutory and academic training body.

(f) Certificates from courses and conferences attended: Documentation of assessment can add value to the trainee’s learning experience as well as providing objective evidence of achievement for the trainee. In the case of a failing trainee, it can be used as evidence of failure to progress and to identify specific areas of weakness that may be useful when planning remedial training. Documentation of criterion-referenced assessments provided by the logbooks and Direct Observation of Practical Skills assessments may provide essential evidence for statutory and academic bodies, or for an interview panel of a trainee’s readiness to practice independently as an interventional consultant.

Conclusions

Training in interventional paediatric cardiology is complex and time-consuming. Consistency, passion, hard study, and long working hours are needed to reach an advanced level of knowledge and skill. The dedication and commitment of the trainer is paramount as is the academic infrastructure where the training takes place. Every trainee who passes through our departments must be given ample opportunity and resources to maximise their ability as an interventional cardiologist. Whereas variation between units and countries in the delivery of interventional training strengthens and revitalises our specialty, adherence to core educational principles is an essential component in ensuring high-quality, safe operators who can continue to drive our exciting specialty forward.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Shakeel Qureshi and Dr Grazyna Brezinska-Rajszys for critically reviewing the manuscript.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.