Introduction

Microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism (MOPD) syndrome type 2 is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterised by a mutation in the PCNT gene (21q22.3), Reference Willems, Geneviève and Borck1 with approximately 150 cases reported worldwide. Reference Bober and Jackson2 It represents one of the most common forms of primordial dwarfism with microcephaly. Reference Majewski, Ranke, Schinzel and Opitz3 Commonly associated conditions include bone dysplasia often linked to scoliosis, dental anomalies, insulin resistance leading to diabetes, chronic kidney diseases, cardiac malformations, and overall vascular disease. Reference Bober and Jackson2 Cases of cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and coronary disease are described. Reference Bober and Jackson2,Reference Hall, Flora, Scott, Pauli and Tanaka4 The prognosis of this disease is strongly associated with cerebrovascular complications.

This article presents the case of a 17-year-old girl diagnosed with MOPD type II, who suffered an inferior myocardial infarction. Informed consent for publishing patient information and images was obtained from the patient’s parents.

Case report

A 17-year-old female patient diagnosed with MOPD II syndrome was referred to our paediatric cardiology department for chest pain. Weighing 20 kg and measuring 86 cm in height, her physical characteristics were typical of the disease. Notable features included extreme microcephaly and facial dysmorphia (Figure 1), with a rounded face, short and stocky neck, retrognathia, dysplastic ear lobes, a broad and elevated nasal root, and a wide philtrum. Her surgical history included coxa vara surgery, craniosynostosis surgery, and the placement of transtympanic ventilators. She was on metformin for insulin-dependent diabetes related to her condition. She also had systemic hypertension but was not on antihypertensive therapy at admission. Cognitively, she attended a medical-social institute.

Figure 1 Facial dysmorphia in our patient with Microcephalic Osteodysplastic Primordial Dwarfism type II, frontal ( a ) and side profil photography ( b ).

She had experienced chest pain for over a month, occurring during exertion, resolving spontaneously, and of moderate intensity. An intense episode prompted an emergency consultation. The pain was described as retrosternal, oppressive, radiating to the left arm, and associated with dyspnoea. Initial laboratory tests showed elevated troponin at 318 ng/L and an inflammatory response with a C-reactive protein of 17 mg/L. The electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed ST-segment depression in the inferior territory and ST-segment mirror elevation in precordial leads V1 to V3. Chest X-ray was unremarkable with a normal-sized heart. Echocardiography showed hypokinetic inferior and inferoseptal walls, but overall cardiac function was preserved with a normal ejection fraction. The left ventricle displayed moderate concentric hypertrophy. A previous echocardiography showed a slightly hypertrophic left ventricle without other abnormalities.

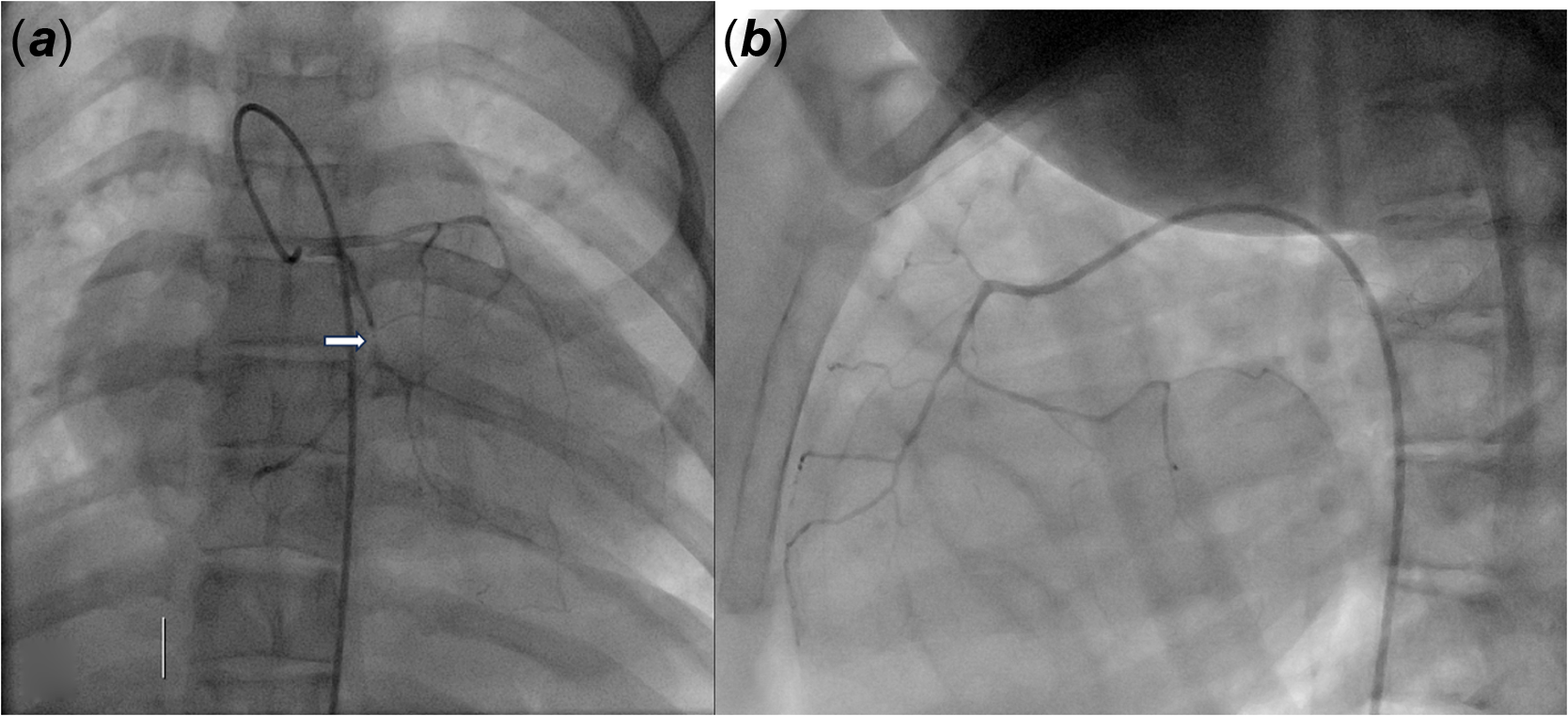

A coronary CT scan revealed subendocardial hypodensity suggestive of ischaemic injury sequelae in the inferolateral territory. Follow-up laboratory tests showed a troponin increase, reaching a maximum of 7600 ng/L within 12 hours of the initial measurement. Diagnostic coronary angiography revealed tri-branch lesions and highlighted a diminutive left and right coronary network with almost complete stenoses or occlusions staggered along the circumflex artery (Figure 2). There was no indication for interventional treatment due to diffuse atheromatous lesions. Medical management was exclusively initiated, including dual antiplatelet therapy, management of cardiovascular risk factors such as dyslipidemia, and cardioprotective treatment.

Figure 2 Conorary angiography (using a four French catheter) revealing tri-branch lesions. ( a ) Contrast injection in left coronary trunk: tiny left coronary network with almost complete occlusions staggered on the circumflex artery over 2,6 mm (arrow). ( b ) Contrast injection in the right coronary: tiny right coronary network.

Discussion

The primary cardiac malformations observed in MPOD II syndrome include persistent patent foramen ovale and atrial or ventricular septal anomalies, affecting approximately 25% of patients. Reference Duker, Kinderman and Jordan5 Neurovascular complications are frequently documented, with recent reports including a case of moyamoya syndrome. Reference Eslava, Garcia-Puig and Corripio6 Duker et al. Reference Duker7 reported on a cohort of 47 MPOD type 2 patients: eight of whom were diagnosed with myocardial infarction in adulthood, with a median age of 24 years (ranging from 17 to 33 years). Some individuals experienced multiple coronary events. A separate case report highlighted a brother and sister with the syndrome who suffered a myocardial infarction in adolescence. Reference Chung, Kim and Kang8 Despite the infrequency of coronary syndrome at this age, regular ECG monitoring is advisable. Vascular monitoring, particularly blood pressure monitoring at the cardiac and renal levels, is recommended due to potential complications associated with MOPDII syndrome, with particular attention to the risk of myocardial infarction approaching adulthood. Reference Eslava, Garcia-Puig and Corripio6 The literature data underscores the necessity for active surveillance of coronary diseases from adolescence onward, given that these patients share the same risk factors as the general population with coronary issues. Implementing primary prevention strategies for cardiovascular disease could mitigate the occurrence of these coronary events. Recognising this complication in the disease allows for prompt intervention at the onset of initial clinical signs.

Conclusion

This case underscores the need for specific monitoring and prompt management of chest pain in patients with MOPD II syndrome. The patient was diagnosed with myocardial infarction and received medical treatment. Primary prevention should be considered in this high-risk population for coronary artery disease.