In this final section of the Supplement, we will present two articles generated from the annual George Daicoff Lecture Series organized by All Children’s Hospital and The Congenital Heart Institute of Florida, as well as two closely related articles discussing “Mentorship, learning curves, and balance” and “Analysis of outcomes for congenital cardiac disease”.

George Daicoff truly represents one of the founding fathers of our profession. George attended college and medical school at Indiana University, receiving his Bachelor's Degree in 1953, and his Medical Degree in 1956. He then trained at the University of Chicago, where he completed General Surgical training in 1961, and Thoracic Surgical training in 1963. He was an Assistant Professor at the University of Chicago from 1963 to 1967, and during this time, in 1966, he did a Cardiac Surgical Fellowship at the Mayo Clinic with John Kirklin. In 1967, George move to Florida, and was Associate Professor of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery from 1967 to 1970 and Professor of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery from 1970 to 1977, at the University of Florida. George then moved to Saint Petersburg, Florida, where he founded and developed the paediatric cardiac surgical programme at All Children’s Hospital. The Congenital Heart Institute of Florida exists today because of the founding efforts of George Daicoff.

George was also one of the founders of the Congenital Heart Surgeons Society.Reference Jacobs, Ungerleider and Tchervenkov1 The Congenital Heart Surgeons Society was formed in 1972 on the suggestion of Eoin Aberdeen, then at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, to include surgeons of compatible character with a special interest in paediatric cardiac surgery. It was to be a small group of surgeons, patterned after the European Cardiac Surgeon’s Club, with an initial maximum membership set at 16. The initial letter of invitation was sent by Eoin Aberdeen to Phil Ashmore, Doug Behrendt, Aldo Castaneda, George Daicoff, Anthony Dobell, Henry Edmunds, John W. Kirklin, James Malm, Dwight McGoon, Robert Replogle, Albert Starr, and George Trusler. These surgeons were to meet to relate their pioneering operative experiences with complex congenital cardiac defects in a friendly and uninhibited atmosphere. Of those invited, 10 surgeons attended the first meeting, which took place on September 7, 1973, at the Sonesta Beach Hotel, near Miami. The name of this club was discussed, and George Daicoff suggested “Small Heart Club”, while Eoin Aberdeen suggested “Pediatric Cardiovascular Surgery Club”. The group, however, opted for “Congenital Heart Surgeons’ Society”.

George has authored 50 peer reviewed publication during the period of 47 years from 1958 through 2005. His interests include fishing, boating, and his family. In 1996, while I was a Senior Registrar at Great Ormond Street, George sent an e-mail to me about the possibility of my joining the programme in Saint Petersburg. When I later met with Jim Quintessenza to discuss this possibility, Jim told me how young surgeons “stand on the shoulders” of their teachers and mentors. Jim stated that his professional career was established “standing on the shoulders” of George Daicoff (Fig. 1) and offered me a similar opportunity for mentorship with himself. I can state in all honesty that I am “standing on the shoulders” of Jim Quintessenza, who is “standing on the shoulders” of George Daicoff (Figs 2 and 3).

Figure 1 George Daicoff and Jim Quintessenza at the Inaugural Meeting of The World Society for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery in Washington DC, United States of America, Thursday and Friday, May 3 and 4, 2007. Photo taken on Thursday, May 3, 2007.

Figure 2 George Daicoff, Jim Quintessenza, and Jeff Jacobs watching the confetti released from the ceiling at the All Children’s Hospital Happy Heart Party for patients with congenitally malformed hearts. Photo taken Friday, February 13, 2004.

Figure 3 The surgical team of The Congenital Heart Institute of Florida at the time of the Seventh Annual International Symposium on Congenital Heart Disease with Echocardiographic, Anatomic, Surgical, and Pathologic Correlation, sponsored by All Children’s Hospital and The Congenital Heart Institute of Florida, Friday, February 16, 2007 – Tuesday, February 20, 2005. Shown from left to right are Jessica Jacobs, Jeff Jacobs, Harald Lindberg, Jim Quintessenza, and Paul Chai. Photo taken Friday, February 16, 2007.

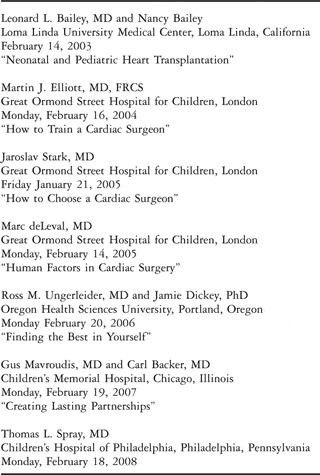

In 2003, in order to honour George Daicoff, the Lecture Series in his name was established by the Congenital Heart Institute of Florida and All Children’s Hospital. Table 1 lists the lectures presented in this Lecture Series since its inception in 2003. In this Supplement, we will present summaries of the two most recent of these lectures. In 2006, Ross Ungerleider and his wife Jamie Dickey, presented a motivational lecture titled “Finding the Best in Yourself”. In 2007, Gus Mavroudis and Carl Backer, professional partners for the past 18 years, presented an equally motivational talk titled “Creating Lasting Partnerships”.

Table 1 The George R. Daicoff Lecture Series.

From their 2006 Daicoff Lecture, Ross and Jamie have created a summary manuscript titled “Managing the Demands of Professional Life” that provides insight into the challenge of achieving both professional success and personal happiness. They discuss the challenges associated with achieving balance in life and its importance for all relationships, professional and personal. Five important concepts are presented:

• Mindfulness

• Intentionality

• Mindsight

• Forgiveness through shared meaning

• Stress awareness and management

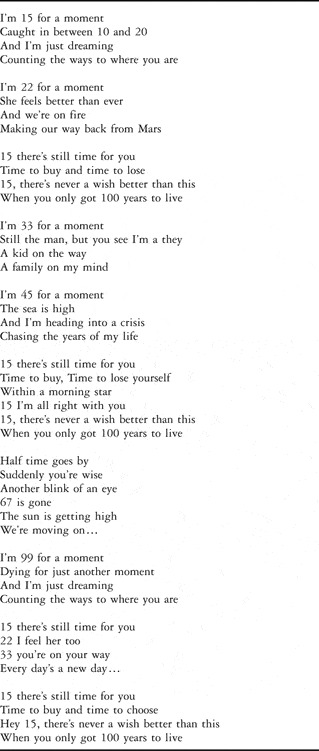

Table 2 shows the haunting words in the song “100 Years” by the musical group Five for Fighting. After the 2006 Daicoff lecture, I am frightened every time I hear this song. It certainly causes me to take a moment and think! The decision to publish this 2006 Daicoff Lecture focusing on personal relationships one year late was intentional, because we felt it would complement the publication of the 2007 Daicoff Lecture that focuses on professional relationships.

Table 2 Five For Fighting – 100 Years lyrics.

From their 2007 Daicoff lecture, Gus and Carl have created a summary manuscript titled “The Influence of Plato, Aristotle, and the Ancient Polis on a Congenital Heart Surgery Program: The Virtuous Partnership”. Jim Quintessenza and I have now been partners for 9 years. When we decided to invite Gus and Carl to speak at the 2007 Daicoff lecture, Jim and I discussed how many paediatric cardiac surgical partnerships were currently in existence in the United States of America that lasted longer than our 9 years. We came up with four: Gus Mavroudis and Carl Backer, Tom Spray and Bill Gaynor, Frank Hanley and Mohan Reddy, and John Mayer and Pedro del Nido. Long lasting professional partnerships are rare and special. Gus and Carl provide insight into this phenomenon.

After the two articles generated from the 2006 and 2007 Daicoff Lectures, we close out the Supplement with two articles discussing mentorship, learning curves, balance, and the analysis of outcomes. In the first article, we will analyze several professional and personnel challenges that health care professional must face. We will define the challenge, illustrate the challenge with some generalized examples, further illustrate the challenge with some personal, and in some cases very personal, examples, and finally, propose solutions to address these challenges.

The task of establishing an appropriate balance between professional and personal life can be extremely challenging. This balance is unlikely to be achieved unless effort is focused into this area. Ross Ungerleider has emphasized the importance of developing appropriate tools to create balance in life. One such tool is the act of writing the word “YES” on one side of a sheet of paper, and writing the word “NO” on the other side of this sheet of paper. When asked to take on an additional professional responsibility, such as sitting on a new committee, presenting a lecture, or writing a manuscript, two possible answers exist: “YES” or “NO”. A “Yes” answer to the new additional professional responsibility is a “No” answer to the personal life and family. A “No” answer to the new additional professional responsibility is a “Yes” answer to the personal life and family. It is not possible always to say “no” to professional responsibilities and commitments, and “yes” to family responsibilities and commitments, without risking career stagnation or unemployment. It is also not possible always to say “yes” to the professional responsibilities and commitments, and “no” to family responsibilities and commitments, without risking unhappiness and growing old alone. The proper balance is a very individualized decision and does not occur accidentally – conscious effort is required!

The “Yes/No medallion” is based on much of the work of Virginia Satir.Reference Satir, Banmen, Gerber and Gomori2 This medallion is one of seven tools that Ross and Jamie refer to these as internal resources,3 but Satir originally termed “self esteem tools.” In an e-mail to me, Ross has summarized the additional six tools:

• A courage stick to remind all of us to stand up for ourselves, even when doing so is scary and may create problems; it is often needed to fully utilize the yes/no medallion.

• A wisdom box to remind all of us that we have internalized a lot of wisdom from our own life’s experiences, which we need to remember to tap into, rather than always just taking advice from others. This tool is especially useful when there are very difficult problems because we will often know best what to do.

• A wishing wand to help us connect with our wishes for ourselves. It is important to know what we wish for so that we can be intentional. Ross likes to remind people that this is a wishing wand and not a magic wand. Just because we wish for something doesn’t mean that we will get it, or that we should get it. But, it is important to know what we want so that we can try to attain it.

• A golden key, which is our key to open doors for possibilities. We often need a courage stick to use this key. It is taking the risk to try new things that may lead to our wishes.

• A detective hat to remind us that we are smart and if we stop and think, we can figure things out.

• A heart to remind us to have compassion for ourselves, and others, as we struggle with life’s challenges.

Finally, in the closing article of the Supplement, Gil Wernovsky, Martin Elliot, and I ask the question: “Analysis of outcomes for congenital cardiac disease: can we do better?” Between 1998 and 2007 inclusive, the databases of The European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery and The Society of Thoracic Surgeons have been used to analyze outcomes of over 100,000 patients undergoing surgical treatment for congenital cardiac disease. Our review discusses the historical aspects, current state of the art, and potential future advances in the areas of nomenclature and databases for the analysis of outcomes of treatments for patients with congenitally malformed hearts. We should eventually create a multi-institutional database for congenital cardiac disease that spans geographic, subspecialty, and temporal boundaries. Analysis of outcomes must move beyond mortality, and encompass longer term follow-up, including cardiac and non cardiac morbidities, and importantly, those morbidities impacting health related quality of life. Methodologies must be implemented in our databases to allow uniform, protocol driven, meaningful long term follow-up. Information allowing for the identification of individual patients needs to be included in multi-institutional databases in order to achieve meaningful long term follow-up. Regulations designed to protect patient privacy, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act in the United States of America, must be respected. We must solve the legal, technical, financial, and ethical issues using methodology that respects patient privacy and these regulations. Methods of the analysis of outcomes of the treatment of patients with congenitally malformed hearts continue to evolve, with continued advances in the areas of nomenclature, database, stratification of case complexity, verification of data, subspecialty collaboration, and the development of standardised protocols for life-long follow-up.

In this final section of the Supplement, therefore, we pay tribute to one of the founding fathers of our profession, George Daicoff. We review several related topics that all fall under the general heading of professionalism. For those charged with the task of caring for patients with congenitally malformed hearts, professional success and happiness require an understanding and appreciation of the topics of professional relationships, personal relationships, mentorship, learning curves, balance, and the analysis of outcomes of treatments for our patients.