Introduction

CHD refers to a wide range of cardiac disorders present at birth. The medical treatment for most of the children suffering from these conditions includes surgery, either corrective or palliative, within their first years of life. Reference Vervoort, Zheleva, Jenkins and Dearani1 If this is delivered in time, the prognosis is relatively good, and 85% of children may reach adulthood. Reference Bhat and Sahn2 However, in many parts of the world, access to healthcare continues to be a problem for this patient population. Reference Vervoort, Zheleva, Jenkins and Dearani1

Access to healthcare is a key building block of healthcare systems, which includes availability of facilities, resources and professionals, but also other aspects related to contact with the health system and the use of services, such as the delivery of information, financing and referral procedures. An adequate healthcare system that provides access to the population is crucial for achieving universal healthcare coverage, Reference Mills3 which is a goal endorsed by many governments and international organisations such as the United Nations; 4 however, it is not available to all who need it. Furthermore, it is argued that access to healthcare is essential to protect human rights, as governments are obliged to “adopt appropriate legal, budgetary, and other measures to ensure that individuals’ human rights are fully realized”. 5 Ensuring proper access to healthcare requires not only the provision of sufficient healthcare by governments but also the participation of national stakeholders in the policy-making process, including civil society and non-governmental organisations. 6

CHD affects children from all social groups in countries around the world, Reference Moller, Taubert, Allen, Clark and Lauer7–Reference Mulder9 and even though the incidence of CHD is relatively low—approximately 1% of newborn children Reference Moller, Taubert, Allen, Clark and Lauer7 —it cannot be considered an orphan disease. 10 Consequently, it does not benefit from the policies designed to improve healthcare for diseases grouped in this category. There are a number of non-government organisations, scientific societies, and academic institutions providing support and advocacy, mostly in high-income countries but also in low- and middle-income countries. Nevertheless, they frequently tend to work without proper coordination, Reference Vervoort, Zheleva, Jenkins and Dearani1 leading to less social visibility.

Patients suffering from CHD frequently face significant barriers to accessing healthcare, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Reference Salgado, Lamy, Nina, Melo, Lamy Filho and Nina11–Reference Sabatino, Dennis and Sandoval-Trujillo15 This means that care is not always provided, leading to more than 260,000 deaths each year worldwide, concentrated mostly in low- and middle-income countries. Reference Zimmerman, Smith and Sable16 Access to treatment for patients with CHD is of particular interest because there are features that make the treatment of these diseases different from other conditions. As is the case of common paediatric cancers, CHD requires intensive use of healthcare resources, and many parents are not able to afford these costs when health insurance coverage is not available. Reference vervoort, Vinck, Kishore Tiwari and Tapaua14,Reference Kowalsky, Newburger, Rand and Castañeda17 Furthermore, it is often the case that the provision of services is restricted to a limited number of facilities, Reference Salciccioli, Oluyomi, Lupo, Ermis and Lopez18 decreasing availability. Additionally, the CHD diagnosis is often difficult and many low- and middle-income countries do not have the resources or policies to carry it out and the referral process is not always well organised.

There is evidence of the barriers to access to treatment for children with CHD from high-income countries, which has been summarised in systematic and scoping reviews. In these studies, socio-economic and geographic issues Reference Davey, Sinha, Lee, Gauthier and Flores19 and non-reimbursement of some treatments Reference Dold, Hass and Apitz20 have been identified as barriers to access. A scoping review on a different population, namely children suffering from cancer in low- and middle-income countries, showed that factors such as misconception, stigma, and hierarchical relationships between parents and healthcare providers played a significant role in making communication and healthcare provision more difficult. Reference Graetz, Garza, Rodrigguez-Galindo and Mack21 These factors may also thwart access to healthcare for children with CHD in low- and middle-income countries.

Synthesising and analysing the available evidence are needed to provide a deeper understanding of this problem. This information is vital to identify key barriers that explain the lack of access to healthcare for these children. This can help design and implement information-based policies to increase the provision of care for these children, and in this way reduce preventable deaths in this population. Consequently, this systematic literature review aims to systematically analyse the existing information on the key barriers to access to treatment for children with CHD, summarising the main reported findings and identifying factors that make access more difficult. Additionally, it is possible to identify potential knowledge gaps that may lead to further scientific research. Increasing the knowledge on this issue is a priority because CHD is a leading preventable cause of disability, and even death, for many children in low- and middle-income countries, Reference Vervoort, Zheleva, Jenkins and Dearani1 and informed and efficient healthcare policies could help to increase access and improve healthcare outcomes for these children in these countries.

Materials and methods

This review uses the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA; see checklist in Annex 1). A protocol was developed and registered in PROSPERO (ID number 470589).

The main outcome we focused upon in this study was access to healthcare for a specific population, namely children suffering from CHD. The context was low- and middle-income countries, defined by the World Bank as those countries having a gross national income per capita lower than US$13,205 22 (see Annex 2).

The PICOTS framework was used to define relevant inclusion and exclusion criteria, which included: (1) articles focused on children with CHD; (2) describing the process of healthcare access or concrete barriers to it; (3) published after 2000; (4) in low- and middle-income countries; (5) qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods studies; and (6) in English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese. Articles that did not meet the previously mentioned criteria were excluded. Annex 3 provides more information on the selection criteria.

The following databases were consulted for relevant academic literature: PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (WoS). Additionally, the reference lists of relevant articles were scanned to find studies not identified by the initial search.

Based on the main objective of this study, the following key concepts were identified: healthcare access, healthcare barriers, CHDs, paediatric patients and low- and middle-income countries. These concepts were used with different syntaxes, according to each database’s nomenclature, leading to different search strings for each database, which are available in Annex 4. References found were exported to EndNote and duplicates were removed using an internal algorithm and checked manually.

The selection of articles was done in three steps. First, titles and abstracts were screened to identify studies that met the inclusion criteria. A second researcher verified the selection of a sample of articles. All discrepancies were discussed by both researchers and a consensus was reached on the inclusion of each article. Agreement was reported appropriately. Then, full texts were screened to select articles that investigated access to healthcare for this population. Finally, the reference lists of the selected publications were reviewed using the same inclusion criteria. The relevance of the literature sources was judged according to the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The analysis used Lavesque’s framework for identifying facilitators and barriers to patient-centred healthcare access, Reference Levesque, Harris and Russell23 which includes six steps for effective provision, and five healthcare features and five patients’ skills that enhance or impede access. Based on this framework, an extraction matrix was developed in Microsoft Excel (v. 16.78.3). A summary of the main findings of each publication was included in the extraction matrix. One author (RL) charted the data, and this file was reviewed by another author (WS), discussing discrepancies. Information was then organised into tables and analysed using qualitative thematic analysis, using categories from Lavesque’s framework. Reference Levesque, Harris and Russell23

The quality of the scientific publications was assessed by means of standardised evaluation checklists based on the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) quality appraisal tool checklists for qualitative 24 and quantitative 25 studies, paying particular attention to validity and reliability, i.e., where the source came from and whether it had been peer-reviewed.

Results

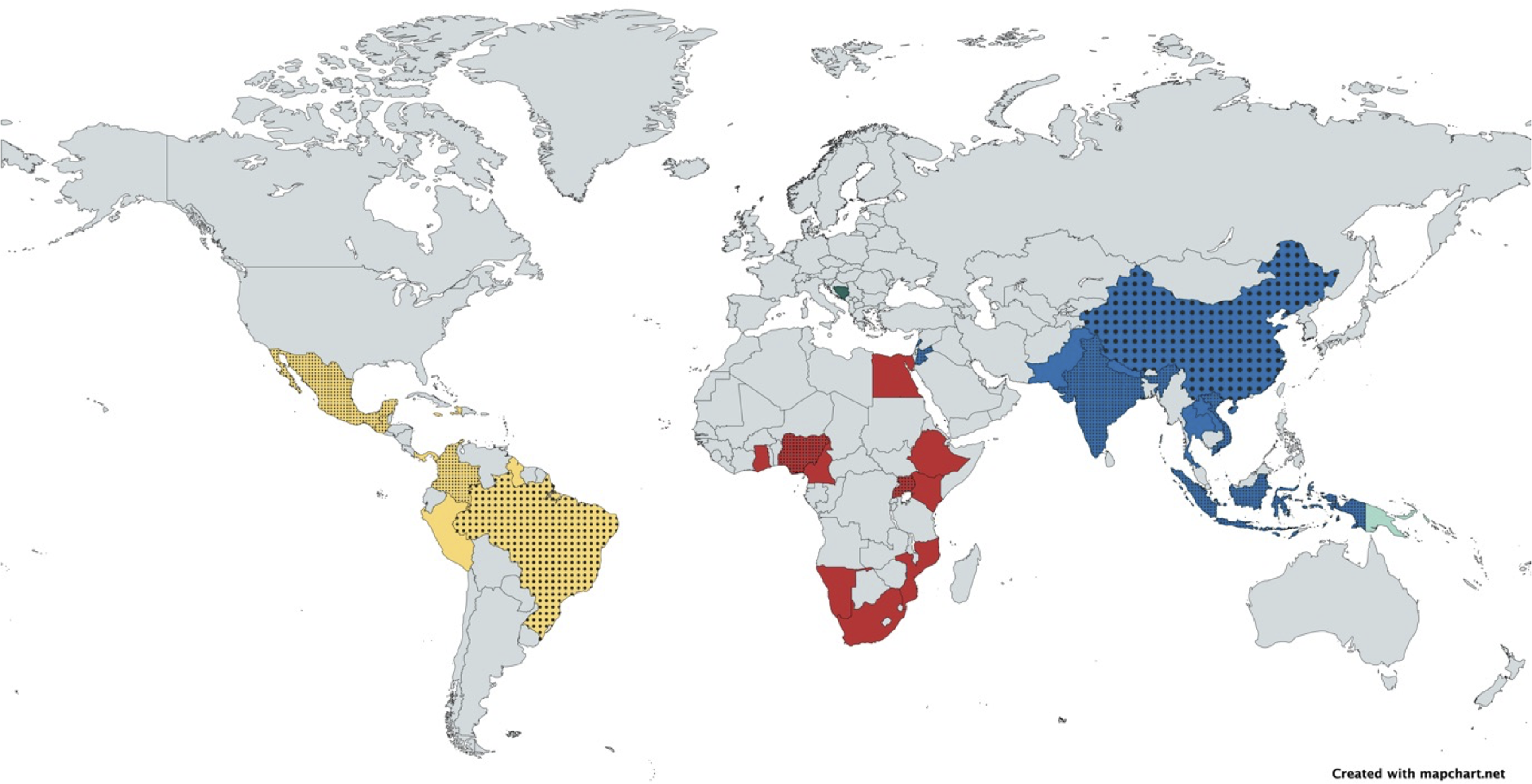

The literature search was conducted in October 2023 and yielded a total of 1,578 articles (1206 in PubMed, 167 in Scopus, and 205 in Web of Science). After eliminating duplications, a final list of 1,448 articles was screened by one author (RL), and a sample of articles was independently reviewed by another author (WS), according to the aforementioned stages. The agreement between them was 95.5% (kappa coefficient 0.7575; a sample of 35% of identified articles) for the title screening and 88.5% (kappa coefficient 0.7636; a sample of 30% of selected articles) for the abstract screening. The final selection of articles is depicted in Figure 1. Table 1 provides a summary of the 57 selected articles. Figure 2 shows countries where articles were selected from. See Annex 5 for publication details.

Figure 1. Flow diagram showing the identification and selection process of articles.

Figure 2. World map showing the countries from which articles were selected. If more than 1 article was selected, the country is dotted.

Table 1. Description of selected articles

Studies have different sample sizes depending, among others, on the context and the approach, qualitative or quantitative. In addition to traditional clinical studies, we identified some reports describing the experience of a single centre or non-government organisation in a narrative way, while others used existing databases and estimates according to projections. The number of participants in articles included in this review ranged from 10 to 15,066. In terms of quality, quantitative studies obtained an average score of 7.9 points (out of 12), whereas qualitative studies scored 5.7 (out of 10). However, not all studies could be assessed, given the different methodologies used.

To analyse the content of the publications further, we used Levesque’s model, which distinguishes different types of access barriers for both the health system and patients, acting at different levels of the clinical encounter. Given that the barriers of the system and of the patients are closely related and in practice are the expression of the same phenomenon on one side or the other, it was decided to analyse the barriers in pairs. In this way, the stages of the medical care delivery process that present barriers are better illustrated (Table 2).

Table 2. Barriers according to different stages of the healthcare provision

The selected articles revealed barriers in all stages of the medical care delivery process, with barriers being most reported in the availability/ability to reach stage, with 44 articles (78.6%), followed by appropriateness/ability to engage and affordability/ability to pay, mentioned in 43 articles (76.8%) each, then approachability/ability to perceive, with 38 articles (67.9%), and finally acceptability/ability to seek, which were reported in 21 articles (37.5%). A geographical analysis of the stages in which the barriers were described provides interesting results, which are depicted in Annex 6.

In the first phase of the healthcare delivery process, which relates to approachability and the ability to perceive, the articles showed that there are several factors that make access a difficult task. In many contexts, a significant proportion of children are born at home, so they receive little or no neonatal medical care. Reference Choi, Shin and Heo13,Reference Kiran, Nath and Maheshwari26–Reference Saxena28 Furthermore, families do not know what symptoms could be explained by CHD, so they do not perceive the need for healthcare. Reference Salgado, Lamy, Nina, Melo, Lamy Filho and Nina11,Reference Choi, Shin and Heo13,Reference Phuc, Tin and Cam Giang29–Reference Bansal, Patel and Lacossade33 At the same time, health professionals themselves often do not have the necessary skills and resources for the screening of these diseases. Reference Kiran, Nath and Maheshwari26,Reference Rashid, Qureshi, Hyder and Sadiq27,Reference Saxena34–Reference Murni, Wibowo and Arafuri37 If despite these factors, the diagnosis is assumed, the referral process to a tertiary level facility is complex. Reference Mills3,Reference Kowalsky, Newburger, Rand and Castañeda17,Reference Ezzat, Saeedi and Saleh30,Reference Bansal, Patel and Lacossade33,Reference Saxena34,Reference Al-Ammouri and Ayoub38–Reference Ibbotson, Luitel and Adhikari44 All these factors delay the diagnosis, often limiting the therapeutic options available. Reference Tefuarani, Hawker, Vince, Sleigh and Williams45–Reference Edwin, Entsua-Mensah and Sereboe48

The second stage of the care delivery process was related to acceptability and the ability to seek. These were the least reported barriers in the selected articles. Among the cultural factors that could become barriers to access are gender biases, Reference Kiran, Nath and Maheshwari26,Reference Saxena28,Reference Ramakrishnan, Khera and Jain49 the advice of traditional healers, Reference Phuc, Tin and Cam Giang29,Reference Bansal, Patel and Lacossade33,Reference Saxena34,Reference Ibbotson, Luitel and Adhikari44 distrust of Western medicine, Reference Salgado, Lamy, Nina, Melo, Lamy Filho and Nina11,Reference Choi, Shin and Heo13 long waiting lists, Reference Maheshwari, Animasahun and Njokanma50 and communication issues. Reference Salgado, Lamy, Nina, Melo, Lamy Filho and Nina11,Reference Saxena28,Reference Olarte-Sierra, Suarez and Rubio31–Reference Bansal, Patel and Lacossade33,Reference Isaac, Nagesh and Bell36,Reference Ibbotson, Luitel and Adhikari44,Reference Jenkins, Castaneda and Cherian51,Reference Staveski, Parveen, Madathil, Kools and Franck52 The latter factors contribute to increased anxiety and distress for families when dealing with healthcare institutions. Reference Ezzat, Saeedi and Saleh30,Reference Xianf, Su and Liu53

Barriers related to availability and the ability to reach were the most common issues in the selected articles. The availability of care can be broken down into material and human resources, Reference Phuc, Tin and Cam Giang29,Reference Saxena34,Reference Aliku, Lubega and Namuyonga40,Reference Altamirano-Diaz, Norozi, Seabrook and Welisch41,Reference Tefuarani, Hawker, Vince, Sleigh and Williams45–Reference Edwin, Entsua-Mensah and Sereboe48,Reference Maheshwari, Animasahun and Njokanma50,Reference Kumar and Shrivastava54–Reference Castro, Zuniga, Higuera, Carrion Donderis, Gomez and Motta66 but some articles point to more specific aspects, such as the possibility of receiving training in the care for these children, Reference Hwang, Sisavanh and Billamay35,Reference Isaac, Nagesh and Bell36,Reference Kumar and Shrivastava54,Reference Bastero, Staveski and Zheleva67 the procedures for acquiring consumables, Reference Aliku, Lubega and Namuyonga40 and the availability of medications. Reference Orubu, Robert, Samuel and Megbule68 Regarding the ability to reach healthcare facilities, the most mentioned barrier was the distance to the centre where the surgery can be performed, Reference Choi, Shin and Heo13,Reference Kowalsky, Newburger, Rand and Castañeda17,Reference Olarte-Sierra, Suarez and Rubio31,Reference Bansal, Patel and Lacossade33,Reference Saxena34,Reference Shidhika, Hugo-Hamman and Lawrenson43,Reference Ibbotson, Luitel and Adhikari44,Reference Awori, Ogendo, Gitome, Ong’uti and Obonyo47,Reference Aliku, Lubega, Lwabi, Oketcho, Omagino and Mwambu56,Reference Khongphatthanayothin, Layangool, Sittiwangkul, Pongprot, Lertsapcharoen and Mokarapong69–Reference Mattos, Hazin and Regis71 along with the costs of travel, which will be discussed later. This is why a number of authors advocate the establishment of more paediatric cardiac surgery centres. Reference Saxena34,Reference Maheshwari, Animasahun and Njokanma50,Reference Aliku, Lubega, Lwabi, Oketcho, Omagino and Mwambu56,Reference Ekure, Sadoh and Bode-Thomas61

In terms of affordability and the ability to pay, the barriers detected in the selected articles recognise that these treatments have a high cost, Reference Kiran, Nath and Maheshwari26,Reference Aliku, Lubega and Namuyonga40,Reference Animasahun, Johnson and Ogunkunle57,Reference Ekure, Sadoh and Bode-Thomas61,Reference Orubu, Robert, Samuel and Megbule68 although this would be lower in some low- and middle-income countries. Reference Maheshwari, Animasahun and Njokanma50,Reference Kim, Seshadrinathan, Jenkins and Murala65 The intensive use of resources that these pathologies imply constitutes a barrier in itself, particularly for low-income families. Reference Rashid, Qureshi, Hyder and Sadiq27,Reference Murni, Wibowo and Arafuri37,Reference Awori, Ogendo, Gitome, Ong’uti and Obonyo47–Reference Ramakrishnan, Khera and Jain49,Reference Xianf, Su and Liu53,Reference Raj, Paul and Sudhakar60,Reference Castro, Zuniga, Higuera, Carrion Donderis, Gomez and Motta66,Reference Sadoh, Nwaneri and Owobu70,Reference Okonta and Tobin-West72–Reference Zhang, Geng and Shao74 Furthermore, governments in low- and middle-income countries do not always have the resources to deal with them, so treatment must often be paid for by the families themselves, Reference Bansal, Patel and Lacossade33,Reference Hwang, Sisavanh and Billamay35 or is done in private centres. Reference Saxena34,Reference Aliku, Lubega and Namuyonga40,Reference Aliku, Lubega, Lwabi, Oketcho, Omagino and Mwambu56 It is noteworthy that people in many of these contexts lack appropriate health insurance, Reference Choi, Shin and Heo13,Reference Kowalsky, Newburger, Rand and Castañeda17,Reference Kiran, Nath and Maheshwari26,Reference Saxena28,Reference Ezzat, Saeedi and Saleh30,Reference Al-Ammouri and Ayoub38,Reference Altamirano-Diaz, Norozi, Seabrook and Welisch41,Reference Palacios-Macedo, Merz and Cabrera42,Reference Kumar and Shrivastava54,Reference Macumbi55,Reference Animasahun, Johnson and Ogunkunle57,Reference Raj, Paul and Sudhakar60,Reference Okonta and Tobin-West72,Reference Zhang, Geng and Shao74–Reference Al-Ammouri, Daher and Tutunji76 which does not happen in all countries. Reference Phuc, Tin and Cam Giang29 These facts would make financial matters a difficult barrier to overcome for many families. Furthermore, one of the aspects that is often not considered in the treatment of chronic diseases, is indirect costs, such as travel costs and loss of revenue, Reference Choi, Shin and Heo13,Reference Olarte-Sierra, Suarez and Rubio31,Reference Saxena34,Reference Ibbotson, Luitel and Adhikari44,Reference Maheshwari, Animasahun and Njokanma50 which is partially mitigated in some contexts. Reference Vivan, Comitis, Naidu, Hunter and Lawrenson32

As already mentioned, many children are born outside the hospital, so they are not evaluated by professional personnel immediately postpartum, limiting diagnostic options, but even if they are treated, the lack of awareness of health professionals makes the diagnosis a challenge for families. Reference Saxena34,Reference Altamirano-Diaz, Norozi, Seabrook and Welisch41,Reference Tefuarani, Hawker, Vince, Sleigh and Williams45,Reference Awori, Ogendo, Gitome, Ong’uti and Obonyo47,Reference Edwin, Entsua-Mensah and Sereboe48,Reference Murni, Wirawan, Patmasari, Sativa, Arafuri and Nugroho Noormanto64 Problems related to the quality of care are the lack of trained workforce, as commented in availability, and the lack of clinical records that allow evaluation of local protocols and resources. Reference Jenkins, Castaneda and Cherian51,Reference Aliku, Lubega, Lwabi, Oketcho, Omagino and Mwambu56,Reference Nguyen, Jacobs and Dearani58,Reference Sandoval, Kreutzer and Jatene77 In terms of quality of care, one author proposes that resources should be allocated “to support regional centers of excellence” Reference Kumar and Shrivastava54,Reference Nguyen, Jacobs and Dearani58 (p. 5). Another factor associated with the quality of care is poor communication between health professionals Reference Phuc, Tin and Cam Giang29 and poor working conditions. Reference Kim, Seshadrinathan, Jenkins and Murala65,Reference Mattos, Hazin and Regis71 Communication is an important issue because the difficulties that families experience in understanding the situation have already been discussed, which is one of the factors that has been proposed as an explanation for the lack of follow-up, Reference Al-Ammouri and Ayoub38,Reference Shidhika, Hugo-Hamman and Lawrenson43,Reference Awori, Ogendo, Gitome, Ong’uti and Obonyo47,Reference Kumar and Shrivastava54,Reference Sadoh, Nwaneri and Owobu70,Reference Leon-Wyss, Veshti and Veras75 an expression of the ability to engage. However, numerous experiences show that it is possible to engage families by means of tailored programmes. Reference Ezzat, Saeedi and Saleh30,Reference Olarte-Sierra, Suarez and Rubio31,Reference Bansal, Patel and Lacossade33,Reference Ibbotson, Luitel and Adhikari44,Reference Staveski, Parveen, Madathil, Kools and Franck52,Reference Bastero, Staveski and Zheleva67

Discussion

This review analysed the evidence on the key barriers to access to treatment for children with CHD. The results show the wide range of obstacles that children suffering from CHD and their families face during their care journey to receive appropriate healthcare in low- and middle-income countries. Making the diagnosis is the first major issue, both due to lack of knowledge and cultural misconceptions of parents and lack of awareness from the health professionals’ side. If CHD is suspected, access to healthcare and higher-level referral systems are often complex, and in some cases, there are simply no institutions/health professionals capable of providing the necessary care. Another major problem is financing, since these conditions usually require intensive use of resources and, in many countries, health insurance has set limits, exclusions, or caps on the extent of the coverage of these costs. Moreover, the indirect costs of treatment are not covered. Finally, in cases where all these barriers have been successfully overcome, the quality of care may not be assured due to a lack of training programmes for health professionals, clinical records, or other administrative reasons.

It is interesting to note that the distribution of these barriers shows differences depending on the geographical location of the countries. According to the articles included in this systematic review, in Asia, the barriers most frequently reported are mostly related to affordability/ability to pay and appropriateness/ability to engage. In Africa, it is mostly the availability/ability to reach and affordability/ability to pay, whereas in the Americas, appropriateness/ability to engage and approachability/ability to perceive account for more reported barriers. These differences could be linked to the level of development of paediatric cardiovascular surgery programmes in each continent, although the differences between countries within a continent are frequently as large as those between continents. In Latin America, for example, there are programmes that have been operational for several decades, while in Africa, many of the few centres have been developed relatively recently. However, these results should be interpreted with caution, given that the realities of the different countries in each continent can be very different. The health systems and resources available in Morocco are not similar to those of Mozambique (the former has centres that carry out surgical interventions for these children daily, while the latter depends on medical missions with health professionals from abroad), although both countries are in Africa. Unfortunately, it is not possible to perform a country-by-country analysis, since in most cases only one report is available for each context. For only two countries more evidence was available: India with 9 articles and Nigeria with 6. It is also important to highlight that the lesser expression of barriers is not necessarily linked to the non-existence of the problem but to underreporting. In Africa, not many barriers linked to the quality of healthcare are reported, but this could be because, in many African countries, the priority continues to be the availability of such care. In the same vein, barriers linked to acceptability/ability to seek were the least reported on all continents, but this is probably because such topics have not been explored in the academic studies included in this review and not because health systems are widely accepted in all contexts.

The following recommendations to reduce barriers to access to healthcare for this population can be drawn from our review findings:

-

Strengthening the capacities of healthcare staff to diagnose these conditions is crucial because although there are simple screening protocols that require few resources, many professionals do not have the knowledge about these procedures.

-

More resources for the treatment of these children should be provided, including indirect costs.

-

Designing a sustainable strategy is essential and long-term financing strategies for this care must be considered, whether through health insurance, public spending, or some type of long-term public-private partnership.

-

Having more paediatric cardiac surgery centres in underserved areas may seem to solve the problem of geographical availability; however, it could actually decrease the quality of care by diminishing the number of surgeries performed at each centre. The solution seems to be more along the lines of organising regional centres of excellence, capable of effectively resolving the pathologies of a given catchment area.

-

In order to give these patients access to these centres, comprehensive and efficient transfer systems should be put in place to ensure the necessary conditions for the transfer of patients and their families.

-

Additionally, advocacy groups could use this information, increasing coordination, and tailoring the message to specific audiences with data based on the most important issues of each region.

These results echo those reported in other similar studies. In a systematic review of CHDs with articles mainly from North America, Davey et al Reference Davey, Sinha, Lee, Gauthier and Flores19 reported that the social determinants of health (i.e. poverty/low socio-economic status, among others) were significantly associated with a lower probability of prenatal diagnosis and less use of healthcare resources, which was operationalised in a similar way to the ability to engage. Among the causal mechanisms proposed to explain this association would be transportation difficulties and lack of health insurance. In a scoping review focusing on a similar population, paediatric patients from low- and middle-income countries, but a different condition, paediatric cancer, Graetz et al Reference Graetz, Garza, Rodrigguez-Galindo and Mack21 reported that communication barriers identified during the provision of healthcare services included misconceptions, stigma, and power relationships between parents and providers. Although in our findings, a number of communication problems between parents and health professionals are shown (which could be related to the ability to engage), findings in this dimension would probably fall into the acceptability/ability to seek category, for which we have less information. This is consistent with the research methodologies described in both systematic reviews because Greatz included 85% qualitative articles, while in our sample only 12.3% of the studies used such methodology. Reference Graetz, Garza, Rodrigguez-Galindo and Mack21

Recently, Cheng et al. published a systematic review of barriers to accessing congenital heart surgery in low- and middle-income countries. Reference Cheng, Heo, Joos, Vervoort and Joharifard79 The fact that there were two systematic reviews shows the high relevance of the topic and the different methodologies used for the search and analysis of results, as well as the different inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selection of articles, make these works complementary in nature. Despite the differences, both systematic reviews point to similar phenomena as possible causes of difficult access to healthcare for this population. In their systematic review, the barriers are temporally classified as pre-, peri-, and post-operative. However, as recognised in the article, many barriers interact with each other, so classification may be problematic. Using a structured approach, such as the categories proposed by Levesque, was useful in overcoming this problem in our case.

One of the main strengths of this systematic review is that it uses a validated framework, such as Levesque’s, to analyse the barriers found in the included articles. In this way, it would not only be possible to compare the results with other contexts in which a similar approach is used, but it is also possible to identify dimensions in which there is less information available, such as acceptability, suggesting future areas for research.

Among the limitations inherent to this type of article, selection bias was managed by cross-checking two authors. Despite the high concordance between them, which speaks of good inclusion and exclusion criteria, some remaining biases cannot be ruled out. Due to the research team’s experience conducting these types of studies, a medical librarian was not consulted, which could have led to a suboptimal search strategy. Publication biases must also be acknowledged. There may be studies that identify barriers but were not published in scientific journals indexed in the search engines used in this systematic review. Remarkably, even if the search criteria included articles in different languages, the vast majority of the selected studies are in English, which could be an expression of this issue. In this same vein, it is possible that there are barriers that have not yet been explored in medical research because researchers are not aware of them. This could be the case of barriers linked to acceptability, which were relatively underreported and might be a relevant knowledge gap to be filled. This study examines barriers to accessing health care for populations in low- and middle-income countries and the research team is made up of academics from high-income country, however, they have vast experience in similar contexts. Finally, the quality of the included studies was not optimal, limiting the validity of these findings.

In conclusion, there are several barriers for children affected by CHD to access healthcare, among which the following stand out: diagnosis, referral systems, lack of qualified institutions/health professionals, financing, inappropriate health insurance, and quality of care. There is no silver bullet to solve the problems, but the solution depends on the health system and the local context. More information is needed to propose solutions tailored to each context, as well as to analyse the effect of potential barriers linked to acceptability.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951124036485.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

None.