Introduction

Social isolation among older adults is increasingly recognized as a major public health concern. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified this issue as a priority to be addressed in the context of an aging population and to promote healthy aging (World Health Organization, 2015). Like many other countries, Canada has recognized social isolation as a national priority, acknowledging the need for concerted action by government, organizations, and communities to address this issue (Employment and Social Development Canada, 2018).

Because of the disparity in how social isolation is defined and measured, estimated prevalence rates among older adults vary widely among scientific and government sources. According to Nicholson (Reference Nicholson2012), recent estimates of the prevalence of social isolation among community-dwelling older adults range from 10 to 43 per cent. In Canada, it is estimated that nearly one in eight (12%) persons 65 years of age or older report feeling socially isolated and nearly one in four (24%) have a low level of social participation (Gilmour & Ramage-Morin, Reference Gilmour and Ramage-Morin2020). The COVID-19 pandemic that began in March 2020 is likely to have a significant impact on the social isolation of older adults. Indeed, more older adults are living alone, they do not use new communication technologies as much as younger generations do, and many of the services they use have been suspended (Douglas, Katikireddi, Taulbut, McKee, & McCartney, Reference Douglas, Katikireddi, Taulbut, McKee and McCartney2020). For these reasons, older adults are likely to be heavily affected by the pandemic confinement measures implemented, such as stay-at-home orders and caregiver visit bans in long-term care facilities (Institut national de santé publique du Québec, 2020; Wu, Reference Wu2020).

The high prevalence rates of social isolation are particularly concerning in light of the large body of literature reporting its adverse effects on the physical, psychological, and cognitive health of older adults (Courtin & Knapp, Reference Courtin and Knapp2017; Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012). Social isolation among older adults has been shown to be associated with cardiovascular disease (Courtin & Knapp, Reference Courtin and Knapp2017), depression (Taylor, Taylor, Nguyen, & Chatters, Reference Taylor, Taylor, Nguyen and Chatters2018), anxiety (Domènech-Abella, Mundó, Haro, & Rubio-Valera, Reference Domènech-Abella, Mundó, Haro and Rubio-Valera2019), and cognitive decline (Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Huntley, Sommerlad, Ames, Ballard and Banerjee2020). In addition, social isolation has been shown to be linked to increased incidence of falls (Petersen, König, & Hajek, Reference Petersen, König and Hajek2020), greater risk of hospitalization (Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, George, Fillenbaum, Park, Burchett and Schmader2008), as well as higher risk of mortality (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris, & Stephenson, Reference Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris and Stephenson2015).

To date, the construct of social isolation has not been well-operationalized. Furthermore, it is frequently confused or used interchangeably with other constructs such as social networks, social support, social integration, social engagement, social participation, and loneliness (Courtin & Knapp, Reference Courtin and Knapp2017; Fakoya, McCorry, & Donnelly, Reference Fakoya, McCorry and Donnelly2020; Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2009).

For some authors, social isolation consists of an objective, unidimensional, and quantifiable concept that is defined as a lack or absence of social contacts with family members, friends, or the wider community (Valtorta & Hanratty, Reference Valtorta and Hanratty2012). In this view, social isolation can be measured with markers such as living conditions (alone or not), number of social ties, or number of social contacts (Courtin & Knapp, Reference Courtin and Knapp2017; Holt-Lunstad et al., Reference Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris and Stephenson2015). An increasing number of authors have adopted a more comprehensive definition of social isolation that includes both objective (e.g., size of social networks, number of social contacts) and subjective indicators (e.g., satisfaction with the social network, sense of belonging to the community, feelings of loneliness) (Gilmour & Ramage-Morin, Reference Gilmour and Ramage-Morin2020; Hawthorne, Reference Hawthorne2006). One of them is Nicholson (Reference Nicholson2009) who identifies five attributes of social isolation, namely: (1) small number of contacts, (2) lack of a sense of belonging, (3) unfulfilling relationships, (4) lack of engagement with others, and (5) low quality of network members. He specifies that number of contacts and engagement with others are objective components of social isolation among older adults, whereas sense of belonging, unfulfilling relationships, and quality of network members are subjective components.

In addition to the lack of consensus regarding the definition of social isolation, there remains a strong propensity to try to find ways to measure it quantitatively (even for the so-called subjective components), in addition to a tendency to view it as something negative for older adults, even pathological, that must be reduced or prevented (see, for example, Nicholson [Reference Nicholson2012]). There has been little research interest in exploring, in a qualitative way, how social isolation is defined and experienced by older people themselves (Cloutier-Fisher, Kobayashi, & Smith, Reference Cloutier-Fisher, Kobayashi and Smith2011).

Among the few qualitative studies on the subject, Cloutier-Fisher et al. (Reference Cloutier-Fisher, Kobayashi and Smith2011) conducted interviews with 28 older adults considered to be at risk of social isolation (based on the size of their social network). The study shows that whereas some older adults find themselves with a small social network as a result of unforeseen circumstances (e.g., the death of a spouse or sibling), others are so “because of a preference for having few social ties and simply enjoying more solitude” (p. 413). As a result, the authors suggest that social isolation can be voluntary and embedded in a lifelong preference to be alone and to engage in solitary activities. Similarly, in a qualitative study that investigated social isolation among 50 community-dwelling older adults with loss of functional autonomy, Couturier and Audy (Reference Couturier and Audy2016) concluded that social isolation was an “adaptive form of partially voluntary social disengagement” [free translation] (p. 138) among some older adults. In fact, many participants reported a desire to be alone or to be left alone, and stressed the importance of their choices about their level of engagement being respected (Couturier & Audy, Reference Couturier and Audy2016). These studies highlight important aspects of the phenomenon of social isolation among older adults; namely, the wants and needs of the older adults. However, these aspects have not yet been fully explored (Newall & Menec, Reference Newall and Menec2019) and are rarely considered when conceptualizing social isolation among older adults.

Finally, Weldrick and Grenier (Reference Weldrick and Grenier2018) critique the current ways of conceptualizing social isolation, highlighting that they tend to focus on the individual level (i.e., individual problem resulting from intrinsic causes) and neglect the social and cultural aspects that are likely to generate and perpetuate social isolation among older adults. In doing so, the authors argue that the links between social isolation and poverty, inequality, and exclusion (which are particularly likely to affect marginalized groups, such as people who have disabilities, who belong to the LGBTQ+ community, or who are from minority ethnic groups) are not well understood. Despite the important contribution of the previous studies, there is a need to deepen our understanding of the phenomenon of social isolation.

This study is the first phase of a large-scale research program that aims to reduce social isolation in older adults living in the Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood (Montreal, Quebec, Canada). To do this, the research program is intended to develop, in collaboration with older adults and their community, various initiatives to be implemented and tested in the neighbourhood to address the challenges of social isolation. This research program is conducted in the context of a Living Lab, as conceptualized by the European Network of Living Labs (2021), and uses co-construction research methods (Dolbec & Clément, Reference Dolbec, Clément, Karsenti and Savoie-Zajc2000).

Considering the gaps in the literature as well as the goals of the large research program, the objective of this study was to describe the social isolation of community-dwelling older adults living in the Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood from the perspective of older adults and representatives of community organizations and municipal services. More specifically, this study aimed to answer the following question: How do older adults and representatives of community organizations and municipal services perceive social isolation among community-dwelling older adults in the Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood?

Methods

This study was conducted using a descriptive qualitative research design (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000) in order to better understand the social isolation of community-dwelling older adults in an urban neighbourhood, from the perspective of the older adults and community stakeholders. This qualitative method is particularly useful for researchers who wish to elicit pragmatic information (e.g., who, what, where) about a phenomenon.

Data were collected through a series of focus groups. This is a preferred method of data collection for a descriptive qualitative study as it allows for a wide range of information and perspectives about events (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000). Furthermore, focus groups are appropriate for investigating complex behaviors and motivations (in this case, social isolation), especially because of the interactions that occur between participants (Morgan, Reference Morgan1996).

In the context of the research program, an operational committee was set up to enable collaborative work between research and community stakeholders. This committee was composed of two employees from community non-profit organizations, one employee from the health care system, three older adults living in the neighbourhood, the principal investigator of the research program (N.B.) and the research coordinator (R.D.L.). For this study, the committee worked on the identification and recruitment of participants for the focus groups. Members were also invited to comment on the interview guide prior to the focus groups.

This research project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee on Aging and Neuroimaging of the CIUSSS du Centre-Sud-de-l’Île-de-Montréal (CER VN 19-20-31), as well as by the Science and Health Research Ethics Committee of the Université de Montréal (CERSES-19-124-R).

Study Settings

The Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood is located in Montreal (Quebec, Canada). In 2016, there were 99,540 people living in the territory of this district (Paquin, Reference Paquin2018), whereas Montreal had a total population of 1,704,694. Côte-des-Neiges covers an area of 11.6 km2 and is home to four large hospitals (including one geriatric hospital), the Université de Montréal and its affiliated schools, more than 84 community organizations, two municipal libraries, and a Maison de la culture (cultural center) (Savoie, Reference Savoie2017). One notable characteristic of this district is that it represents an important entry point for immigration to Canada. In 2016, there were 58,200 immigrants in Côte-des-Neiges (60% of the population) (Paquin, Reference Paquin2018), making it the Montreal neighbourhood with the largest number of immigrants (Savoie, Reference Savoie2017). By that very fact, Côte-des-Neiges is also distinguished by its ethnocultural diversity. It is estimated that approximately 34 per cent of the population identifies itself as being of European origin, 31 per cent identifies itself as being of Asian origin, 12 per cent identifies itself as being of African origin, 5 per cent identifies itself as being of Caribbean origin, and 4 per cent identifies itself as being of Latin American origin (Savoie, Reference Savoie2017). In this neighbourhood, 30 per cent of people living in private households are considered to have a low income level and 79 per cent of households are composed of renters (compared with 15% and 39%, respectively, for the province of Quebec) (Paquin, Reference Paquin2018). Despite lower than average incomes, members of this neighbourhood are well educated, with 46 per cent of the population having a university degree and only 12 per cent of the population being without a high school diploma (compared with 24% and 20%, respectively, for the province of Quebec) (Paquin, Reference Paquin2018).

Regarding the older adult population, there were 13,630 people 65 years of age and older in Côte-des-Neiges in 2016, representing 14 per cent of its population (≥ 75: 7%; ≥ 85: 2%) (Paquin, Reference Paquin2018). These percentages are slightly below or equal to those for the province of Quebec (≥ 65: 18%; ≥ 75: 8%; ≥ 85: 2%) (Paquin, Reference Paquin2018). In Côte-des-Neiges, 38 per cent of people 65 years of age and older live alone (Lemieux, Markon, & Massé, Reference Lemieux, Markon and Massé2016), 28 per cent are considered to have a low income level (Paquin, Reference Paquin2018) and 41 per cent have one or more disabilities (Markon, Reference Markon2017).

Participants and Sampling

The focus groups were conducted with different categories of key stakeholders of the neighbourhood; namely, community-dwelling older adults, and employees of community organizations and municipal services. Consulting employees of community organizations and municipal services allowed us to gain their perspective on the structural and organizational issues of older adults’ social isolation, which was complementary to that of older adults. It also provided access to part of the reality of very isolated older adults who were difficult to recruit for the focus groups or older adults whom it was not possible to meet in this study (e.g., because of language or transportation issues). Some of the older adults we recruited for the focus groups and who were actively involved as volunteers in neighbourhood community organizations that offer services to isolated older adults (e.g., friendly visits) were also able to provide information about the reality of the people they serve. In this way, these volunteers could talk about both their own experience and that of isolated older adults in the neighbourhood.The exact number of focus groups to be conducted was not determined in advance. Because the project was conducted in a Living Lab context, the study protocol aimed to recruit members from each of the stakeholder categories deemed relevant to the issue of social isolation among older adults, in order to represent all perspectives. Accordingly, the final sample size was determined based on the representativeness of our sample (not data saturation) (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2020). The desired group size for each focus group was from three to six participants (Morgan, Reference Morgan1996).

A variety of targeted recruitment strategies were used, including snowball and quota sampling (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2020). The goal of these strategies was to obtain cases that were deemed to be information rich with respect to the topic under study (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000). Thus, the recruitment of older adults was initiated by the members of the operational committee, who acted as intermediaries for the recruitment in their respective settings (e.g., community center, residence for older adults). A promotional hand-out poster was created to support committee members in recruiting participants. Relevant individuals to be invited as representatives of community organizations and municipal services were identified by the members of the operational committee. These individuals were then approached by the research coordinator (R.D.L.) to invite them to participate in the study.

To participate in the study, older adults had to be 65 years of age or older and reside in the Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood. To be recruited as community or municipal representatives, the individuals had to work with older adults in the Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood. All participants had to be able to express themselves either in French or English. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the start of their participation in the study.

Data Collection

The focus groups took place between November 2019 and March 2020, just before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. Each group met on one occasion for approximately 2.5 hours, at the Research Centre of the Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Montréal or in any other location in the neighbourhood that was more convenient for the participants (e.g., a common room in a community center, an apartment of an older adult). The meetings were facilitated by a researcher with expertise in conducting focus groups (M.C.). An observer (R.D.L.) was present during the meetings to take notes and validate with the participants the main ideas that emerged from the discussions at the end of each meeting. The discussions were audio-recorded.

All participants were first invited to complete a demographic questionnaire in order to collect information such as their age, gender, level of education, and ethnocultural origin. A question about their connection to the Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood was also included (number of years they had lived and/or worked in the neighbourhood). The interview guide for this study was developed through an iterative process with the entire research program team. Two interview questions were specifically related to social isolation: In your opinion, is there a problem of social isolation among the older adults of Côte-des-Neiges? If so, what factors contribute to the social isolation of older adults in Côte-des-Neiges? Participants were invited to be specific and provide examples of situations that concerned them personally (for older adults) or that concerned other older adults they knew living in Côte-des-Neiges (for older adults and community stakeholders).

Finally, the project coordinator (R.D.L.) kept a log of analytic memoranda to record their questions, personal reflections, and events, as well as the team’s discussions and decisions. Analytic memoranda are useful for remembering events, as well as for linking different pieces of data together (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2020).

Data Analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed following the approach of Miles et al. (Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2020). First, the audio recordings from the focus groups were transcribed verbatim. Next, the first cycle of coding was conducted, attempting to identify the components of social isolation that emerged from the participants’ discourse. Deductive (or a priori) coding was initiated using a provisional list of master codes developed from the five broad categories of Nicholson’s (Reference Nicholson2009) definition of social isolation in older adults. As the coding proceeded, these provisional codes evolved and several additional codes emerged progressively from the data, leading to the creation of sub-codes (inductive coding). First, three focus groups were coded by R.D.L., and an initial validation of the coding list was performed with three co-authors (N.B., M.C., and J.F.). Following this step, the coding of the first three groups was revised by R.D.L., and the four remaining focus group transcripts were coded. A second validation of the coding list from all seven focus groups was performed with the same co-authors. This was followed by a final verification of the coding of all transcripts by R.D.L., resulting in a final coding list.

A second cycle of coding (pattern codes) was conducted, which allowed for the grouping of the codes into themes and subthemes by R.D.L. using matrices (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2020). This second cycle of coding was also validated with the same three co-authors (N.B., M.C., and J.F.). The themes, sub-themes and codes, as well as selected verbatim quotes, were translated from French to English after analysis by the R.D.L. The translation was validated by the co-authors.

QDA Miner software was used to perform the coding of verbatim (first cycle coding), while Word software was used to elaborate the coding list. The online whiteboard platform Miro was used to develop the matrices (second cycle coding).

Situating the Researchers in the Context of this Study

In accordance with Miles et al. (Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2020), we have adopted an approach under the pragmatic realist paradigm. Our research team is interdisciplinary (rehabilitation, gerontology, psychology, health promotion, recreation, and sociology) and composed entirely of women. The members of the research team represent a diversity of ethnocultural backgrounds, although the vast majority are not from a visible minority group. The two research members who conducted all of the focus groups were white women. Team discussions were held throughout the project to reduce the potential for bias related to these aspects on data collection and analysis.

Results

A total of seven focus groups were conducted: four groups with older adults, two groups with employees from community organizations, and one group with employees from the municipal services. Each group included between 3 and 8 participants, for a total sample size of 37 participants.

Description of the Participants

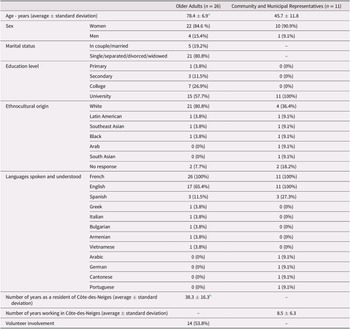

In the older adult sample (n = 26), participants’ age ranged from 67 to 92 years, with an average age of 78 years. The majority of older participants were women (85%) and 19 per cent were in a relationship. The number of years living in Côte-des-Neiges ranged from 5 to 77 years, with an average of 38 years. A little more than half of them were involved as volunteers, mainly in the Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood.

In the community and municipal representative sample (n = 11), participants’ age ranged from 30 to 64 years, with an average age of 46 years. All but one of the participants were women. They all worked in different organizations. The number of years they had been working in the Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood ranged from 1 to 20 years, with an average of 9 years. Two of them had also been residents of the neighbourhood for 2 and 5 years, respectively. See Table 1 for a more complete description of study participants.

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics (n = 37)

Note.

a Missing data for 1 participant

b Missing data for 2 participants

Social Isolation of Older Adults in Côte-des-Neiges

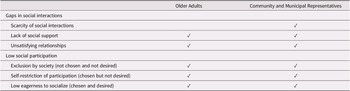

Two themes emerged from the participants’ discourse, namely Gaps in social interactions, and Low social participation. Each of these themes included three sub-themes, as shown in Table 2. These will be discussed in turn, within each of their respective themes. Both participant samples (older adults and representatives from community organizations and municipal services) had a similar perspective on what characterizes the social isolation of older adults in the Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood, with the exception of the scarcity of social interactions, which was mentioned only by community and municipal representatives.

Table 2. Overview of themes and sub-themes emerging from the study participants’ discourse

Nonetheless, older adults stated that social isolation is a difficult phenomenon to grasp considering that there are isolated older adults in the neighbourhood, but that many of them are not known or visible, notably because they do not go out. In addition, the identification of isolated older adults is sometime based solely on subjective observations rather than through an in-depth conversation with these so-called “isolated” individuals.

Well, at the Wilderton Mall, […] I would often see elderly people, with canes and then bent back, and… Having great difficulty walking, with a little shopping cart. Well, I’m sure these people are alone. […] I haven’t spoken to them. I don’t know them but… Yes, they seem lonely to me, from their attitude, and what they do, they are certainly people who are not surrounded. [translation from French] (Focus group #3 – Older adult #2)

Gaps in Social Interactions

In all but one of the focus groups, participants mentioned that social isolation of older adults in Côte-des-Neiges is characterized by gaps in social interactions. This refers to deficiencies in the older adult’s social interactions, both on an objective and subjective level. More specifically, three sub-themes emerged: Scarcity of social interactions, Lack of social support, and Unsatisfying relationships.

Scarcity of social interactions

This subtheme is defined as a person having a small number of social interactions, regardless of the type of relationship with others involved in those interactions (whether relatives, friends, or strangers) or the modality of those interactions (face-to-face or phone). This was reported in the three focus groups with representatives from community organizations and municipal services, in which participants mentioned that for some older adults, social interactions are scarce. As a result, for some of their clientele, the contacts that are made as part of their services (e.g., friendly visits, daily calls, booking tickets in person for an event) represent the only social contacts older adults have.

You can feel it sometimes at the counter, I think, or… even in relation to the public. The person who comes to talk to us, it’s their first social interaction of the week. Then it’s their only social interaction. [translation from French] (Focus group #5 – Community stakeholder #4)

Two community workers from the same focus group explained that this scarcity of social interactions may be exacerbated by the digital transition of many services (e.g., activity registration, check deposit). Before this transition, these activities represented opportunities for older adults to get out of their home and have social interactions.

Lack of social support

This sub-theme is defined as the absence of social relationships to meet the different needs of older adults, from basic (e.g., need to talk to someone) to more complex needs (e.g., need to feel useful), not to mention the more utilitarian needs (e.g., need to buy groceries). Participants in two focus groups of community organization representatives mentioned that, for some older adults, there is no one in their social network to talk to.

I can tell you that our clients are about 80 years old and over. […] It’s certain that yes, they are very isolated in a sense; they have no one to talk to all day… [translation from French] (Focus group #2 – Community stakeholder #4)

Three focus groups (two groups composed of older adults and one group composed of representatives of community organizations) raised the issue of the lack of people available to provide instrumental support to older adults, whether it be for household chores, grocery shopping, or access to health services.

I’m a single person, I have no family. And um, I had hip surgery in August 2017. I’ve been scrambling to get help and then to even have someone come out with me when I’m better […] So it’s being less alone in a case of “force majeure” [an exceptional event that cannot be dealt with]. And this is… I lived that. And this is… terrible. [translation from French] (Focus group #3 – Older adult #2)

In addition, the lack of someone to do meaningful activities with, either at home or in the community, was noted in two groups (one group of older adults and one group of representatives of community organizations). Some older adults discussed that this can happen even to someone who is very busy, has many social contacts during the week, and has family that they see on a regular basis. Therefore, there is a need to have people with whom to do activities and share experiences.

Sometimes you want to go to the theater, you’re alone. Well, you’re not going to go, you don’t feel like it, because you’re alone. Go see a play or a singer […] Or even go to a restaurant, sometimes you want to go to a restaurant. Going alone, is that boring enough? Well then, it’s activities like that that can be added. Sharing, well I don’t know, a show, a play… [translation from French] (Focus group #4 – Older adult #2)

Finally, two focus groups with community organization workers discussed how some older adults lack social interactions that promote a sense of contributing to society or being of value. A participant mentioned that this is particularly likely to happen when the person stops their usual productive activities, such as working, and caring for their spouse.

The usefulness aspect. I don’t know how to translate it, but it’s: “I’m good for something, I’m useful to someone. My absence will be noticed if I don’t do this or that.” […] To go towards the recognition of one’s own usefulness. When it is not there… When you feel that you have nothing more to learn, you have nothing more to give, you have nothing more to do… And if, on top of that, you live alone, then it’s isolation with a capital “I”. [translation from French] (Focus group #2 - Community stakeholder #2)

Unsatisfying relationships

This sub-theme is related to the older adults’ feeling that the social relationships being experienced are not fully satisfying, coupled with a desire for them to continue the relationships in other forms or at a higher intensity.

Several older adults in the same focus group raised the point that there can be a superficiality in their peer relationships that are created later in life (e.g., with neighbours, with other older adults who are met through organized activities). One participant explained that some of their relationships with peers, while pleasant and cordial, are “extremely superficial” when it would sometimes be desirable to develop some of these relationships on a deeper level, that of friendship.

I take the example of outings like we can do with the Senior Center. It’s nice. […] I talk to everyone a little bit, but as soon as we get off the bus, voom, voom, voom, that’s it, it’s over… It’s all very superficial, you can’t expect anything from that. You can expect the outing, and that’s all. [translation from French] (Focus group #4 – Older adult #1)

One participant also expressed dissatisfaction with contacts with friends being made by phone rather than in person. Contacts may have always been this way, especially when friends live far away. On the other hand, it may be something new, caused by one’s own aging, combined with the aging of friends, which results in everyone going out less often.

I think that what there is, to see it with friends who are in the district too, we can stay 3-4-5 months without seeing each other. We talk to each other a little bit, and then well, that’s it, that’s the end of it. [translation from French] (Focus group #4 – Older adult #1)

Finally, a community worker and an older adult involved as a volunteer both reported that some older adults are dissatisfied with the social relationships that have been created in the context of a community organization’s support service. These participants explained that they had experienced situations in which older adults to whom they provided services through a community organization wanted more from the relationship than what was possible in this context.

Then, they want me to go to their house just to talk or, like, you know, call them… You know, one lady in particular is frustrated with me because I don’t call her or come to her house often enough. [translation from French] (Focus group #7 – Community stakeholder #1)

Low Social Participation

In all focus groups, it emerged that the social isolation of older adults in the neighbourhood is marked by low social participation; that is, little or no participation in activities that provide opportunities for social interaction. Following the analysis of the participants’ discourse, low social participation of older adults was divided into three sub-themes; Exclusion by society, Self-restriction of participation, and Low eagerness to socialize. Furthermore, it appeared that low social participation of an older adult could be defined according to two attributes: (1) whether or not this low social participation was chosen by the person and (2) whether or not this low social participation was desired by the person. The three sub-themes of low social participation can therefore be illustrated in a matrix (Figure 1), based on these two attributes.

Figure 1. Matrix of low social participation related to social isolation of older adults from the participants’ perspective

Exclusion by society (not chosen and not desired)

In the upper left quadrant, the sub-theme Exclusion by society relates to the fact that the older adult’s social participation is hindered due to structural factors specific to their environment (including their neighbourhood), such as the cost associated with participation in some activities being too high for them, the lack of transportation to get to the activities or the lack of respite services for older adults who are caregivers. In this case, low social participation is not the result of the older adult’s choice, nor is it desired.

There’s also a barrier for people to get around. There are not enough respite services available for people who are caregivers in the older community, and that, everywhere, to free them up, to have someone stay with their loved one and then to be able to move around and go to activities. [translation from French] (Focus group #7 – Community stakeholder #2)

Being forced to stop participating in a social activity because the activity was discontinued was also mentioned in three of the focus groups with older adults. The cessation of the activity may be the result of a lack of human resources to facilitate the activity or a lack of funding. For some older adults, having to stop participating in these activities was “painful”, as they were meaningful activities for them.

Outings every week, five days a week. There were plays at the library. There were dinner parties… all kinds of things. It was great. He did that for 20 years and then they cut the grants, so he retired. […] There’s no more funding. It takes a grant for that. But it was great. […] because, first of all, it gets us out of here. It gets us dressed, cleaned up, out, meeting people. […] Imagine going to another city and seeing a play. That makes a change, you know. We’re isolated all the time. [translation from French] (Focus group #6 – Older adult #2)

Participants from two focus groups (one group composed of older adults and one group composed of representatives from municipal services) mentioned that some older adults are excluded from a service or an activity due to a decline in their cognitive abilities. A participant reported that older adults who forget to return books to the library too often can have their records blocked and lose all borrowing privileges. In addition, one older adult involved as a volunteer at a community organization from the neighbourhood explained that older adults who show signs of cognitive decline may stop receiving services from the community organization and are referred to adult day care centers instead.

I don’t have much social experience with these people [people with cognitive disorders], because, in reality, they are always referred to day centers. So, when we do visitations and the person’s health deteriorates in this way, well, there are day centers where they come to pick them up in the morning, then they go away all day, then they bring them back at night, so… [translation from French] (Focus group #1 – Older adult #3)

Then, it also emerged from four focus groups (two older adults’ and two community stakeholders’ focus groups) that the slower pace of older adults’ technology shift is often not respected in society, resulting in their exclusion. Although there is less interest in technology among some older adults, it was mentioned that it is often taken for granted that everyone is connected (via a computer or a tablet) and has an email address, which some older adults feel is an “inconvenience” and can prevent them from accessing information.

People assume that everyone has a computer. Whereas, of all the people I’ve been with, in five years, I had just one with a computer. None of the older people I see, even now, have a computer, or a tablet, or anything. So, they take for granted that people are going to find, are going to know but, that’s not true. [translation from French] (Focus group #1 – Older adult #3)

Self-restriction of participation (chosen but not desired)

In the upper right quadrant of the matrix, the sub-theme Self-restriction of participation refers to reduced or limited social participation as a result of a deliberate decision by the older adult. Although the older adult has power over the outcome of this situation of social isolation, this does not mean that this situation is desired by the older adult (e.g., there is still a desire to go out and some people complain about not going out or going out less).

Participants from six focus groups mentioned that some older adults reduce their participation in social activities that take place in the community because they consider it too much effort, too difficult, or too complicated to get out. For some older adults, getting out is perceived as not worth the effort. Several elements, including the person’s difficulty in getting around, aspects of the winter season (e.g., the cold, snowy sidewalks), and obstacles in the physical environment, would lead the person to perceive that going out is too difficult and therefore limit their outing.

They walk with a cane or… And then, in the summer it’s good because they can get around, but in the winter it’s really a big problem. That’s the difficulty for our seniors. It’s not that the activities, that they don’t want to go. It’s that… It’s the reduced mobility. The biggest difficulty is really, it’s to get out of the house. […] Everything is complicated for them, you know… [translation from French] (Focus group #2 – Community stakeholder #4)

In four focus groups, it was reported that some older adults refuse to participate in services or social activities out of fear of stigma. This may be true for activities that are adapted for or dedicated only to older adults, as well as activities held in places where there may be people of younger generations. Regarding activities reserved or adapted for older adults, some would find these activities infantilizing and not corresponding to their interests. In addition, several participants reported that when the suggestion is made to go to an adult day care center, some older adults refuse, saying that they “aren’t there yet”, that it “isn’t for them”, or that “it’s embarrassing”. Participants explained that this may be related to the fact that some older adults may associate participation in these activities with having disabilities.

A lady I volunteer with has a friend like that [who goes to the day center]. But she doesn’t want to go there, because she knows that her friend has disabilities. So she says, “No, no, that’s not for me.” It’s as if she recognizes her friend’s limitations and she goes to play bingo or cards or paint by numbers, but it’s not for her. She’s not there yet, she said. And that’s very important. She’s not there yet. [translation from French] (Focus group #1 – Older adult #3)

Some people sometimes feel unwelcome when they try to join older adults-only activities, which will cause them to withdraw from these activities. As indicated in the following excerpt, it can sometimes be difficult for an older adult to fit into an existing group for which there is no facilitator.

Community dinners, don’t try to introduce a new person to a table. It’s like in the residence… A new person comes in, that we’ve never seen. And then he come up to approach: “No, no, it’s reserved.” And then he goes to the other table: “No, no, no, it’s reserved.” And, the person finds himself… We sit him with the rest of us, with the people from the management. [translation from French] (Focus group #1 – Older adult #4)

On the other hand, it appears that there may be a discomfort among some older adults in going to locations that are also frequented by younger generations. Some older adults said they really liked going to a community center for people 50 years and over, explaining that they would feel less comfortable in a center that was also frequented by younger people, for fear of being judged or laughed at.

Because even during meals, sometimes, he plays Pierre Lalonde. So, well, we appreciate it. We can even sing, we know all the words. It’s good, and there’s no one to judge us. You know: “Ah, have you seen the old woman… Look at her, she’s ashamed of herself.” So, we’re good and we’re not afraid to assert ourselves. You know; “I like Pierre Lalonde, I like Michel Louvain, I like…” But we wouldn’t want to say that to a younger population. […] Because we would be laughed at. [translation from French] (Focus group #3 – Older adult #1)

Low eagerness to socialize (chosen and desired)

In the lower right quadrant of the matrix appears older adults’ low eagerness to socialize, which is related to the fact that the older adult voluntarily withdraws from social situations. This leaves them with little social participation, which is a situation that suits them and from which they do not suffer, as this participant explains:

We’re isolated all the time. Well, I don’t suffer so much from that because I have a happy solitude. But I read a lot and I have the Internet and then I have television. [translation from French] (Focus group #6 – Older adult #2)

Furthermore, a reduction in older adults’ need to socialize was mentioned by participants of five focus groups. According to some participants, this would be particularly true for oldest-old persons (i.e., 80 years of age and older). It appears that these individuals are comfortable at home, have less interest in going out, and prefer social interactions that are shorter and on a one-on-one basis. In addition, some older adults may refuse to go out even when someone offers to accompany them.

Sometimes we want to get them out. We find ways, we would like to get them out. But it’s not really their need to be taken out. They want to stay at home, comfortable, in their habits and then… That’s okay. They don’t really miss the social life. [translation from French] (Focus group #3 – Older adult #1)

Linked to this reduction in the need to socialize, it also emerged from three of the focus groups that there may be a gradual habituation to isolation among some older adults. Therefore, as they age, older adults no longer “function in the same way” and slowly change their pace. There may be an acclimatisation to doing less and being alone more often. As a result, some older adults may come to “shut themselves off”. One participant noted that this social withdrawal can happen insidiously, without the person even realizing it.

It’s a way of life, and you slowly get used to it, willingly. At least, I do. I’ve always learned to live with myself and that’s what I’ve always told my daughter, learn to live with yourself first before learning to live with others. So, it’s not a problem except that it becomes a trap, at some point it’s obvious that it becomes a trap. [translation from French] (Focus group #4 – Older adult #1)

Finally, participants from four focus groups reported a lack of openness to others among some older adults, explaining that they do not engage in social activities. For example, some older adults may be lonely, unsociable, and shy; traits that they have had all their lives. In addition, some older adults may have an “individualist mentality” that means they do not want to get involved and want to “have peace”.

I think it’s that they just want to live their own little life. […] On their own and they feel good about it. [translation from French] (Focus group #6 – Older adult #1)

Discussion

This study aimed to describe social isolation among older adults living in a neighbourhood located in Montreal (Canada), Côte-des-Neiges, from the perspectives of older adults and representatives of community organizations and municipal services. In general, both types of participants who were interviewed had a similar perspective on what characterizes the social isolation of older adults in the Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood. Participants reported that social isolation in the neighbourhood is characterized by gaps in social interactions, whether in terms of a small number of interactions, a lack of certain types of social relationships to meet the person’s needs, and a personal dissatisfaction with social interactions. The social isolation of older adults in the neighbourhood is also characterized by low social participation, which depending on the case may be chosen (or not) and desired (or not) by the older adult. Thus, low social participation of older adults can be broken down into three categories as illustrated above (Figure 1). Although some older adults choose to restrict their social participation as a result of multiple constraints (not desired) or a lack of interest in socializing with others (desired), others are excluded by society without their consent (not chosen and not desired).

Scarcity of social interactions and Lack of social support refer to well-known quantifiable and objective aspects of social isolation that are generally agreed upon in the literature (see, for example, de Jong Gierveld, Van Tilburg, and Dykstra [Reference de Jong Gierveld, Van Tilburg, Dykstra, Vangelisti and Perlman2006], Hawthorne [Reference Hawthorne2006], or Nicholson [Reference Nicholson2009]). It is common to see in studies that social isolation is measured (solely or in part) via the number or frequency of social contacts or interactions (Courtin & Knapp, Reference Courtin and Knapp2017). In addition, some tools have been developed to assess the different types of social support that are available to a person, including the Social Support Survey (Sherbourne & Stewart, Reference Sherbourne and Stewart1991). Results from this study are consistent with some of the types of social support identified in this tool; that is, the availability of someone to listen to you, to get help or assistance from, and to do enjoyable activities with. However, one type of social support that emerged in this study that is less documented in the literature is related to having people who make you feel that you are useful in society; that is, that you can contribute to it and that you have value. Indeed, although the sense of usefulness among older adults has been increasingly explored in recent years (de Boissieu et al., Reference de Boissieu, Guerin, Suissa, Ecarnot, Letty and Sanchez2021), little is known about how to foster the social relationships that make older adults feel that way. This would be an important area for future research, particularly given the links that have been shown to exist between the sense of usefulness and the health and well-being of older adults (Gruenewald, Karlamangla, Greendale, Singer, & Seeman, Reference Gruenewald, Karlamangla, Greendale, Singer and Seeman2007).

The gaps in the social interactions that are related to social isolation of older adults are not solely objective. Indeed, analyses pointed out that some older adults may be dissatisfied with their relationships, which aligns with one of the subjective attributes of social isolation identified by Nicholson (Reference Nicholson2009). According to this author, having unfulfilling relationships consists of being dissatisfied with the relationships you do have, and would be related to the feeling that your needs are not being met. This was particularly evident when participants discussed the notion of superficiality in peer relationships. Indeed, it emerged that the relationships created later in life often remain at a more superficial level than that of friendships (e.g., saying hello to neighbours, chatting with participants at a one-time group outing), which some authors define as casual (Dupuis-Blanchard, Neufeld, & Strang, Reference Dupuis-Blanchard, Neufeld and Strang2009). Although this type of relationship would appeal to many older adults, particularly because it allows for social interaction without having to commit to something (Dupuis-Blanchard et al., Reference Dupuis-Blanchard, Neufeld and Strang2009), some older adults have a need for deeper level relationships in order to feel satisfied and socially connected.

The sub-theme Exclusion by society relates to the fact that the older adult’s social participation is hindered as a result of structural factors specific to their environment (including their neighbourhood). To this end, Weldrick and Grenier (Reference Weldrick and Grenier2018) argue that social isolation is intimately linked with processes of exclusion and inequality across the life course, suggesting that “social isolation in later life can be seen as a by-product of […] accumulated disadvantage or inequalities” (p. 80). Indeed, it appeared from our participants’ discourse that the older adults experiencing social exclusion are in many cases those with disadvantages (mobility issues, cognitive decline, low financial means, belonging to a minority language group). This highlights the importance of continuing efforts to make our communities more inclusive of all people in society.

Qualitative analyses also revealed technological transition as a potential contributing factor to the experience of social isolation among older adults. Other authors raise this issue, including Olphert and Damodaran (Reference Olphert and Damodaran2013) who report that older adults “face the possibility of new forms of social exclusion if they are unable to access the opportunities and services that are increasingly being delivered through the Internet” (p.565). The digital exclusion of older adults is likely to be exacerbated during the pandemic, as more and more services, events, and information are offered in an online-only mode (Seifert, Cotten, & Xie, Reference Seifert, Cotten and Xie2021). Older adults may be deprived of access to important and relevant health information as well as of opportunities for entertainment or social participation. If the use of new technologies and the Internet are to become a condition for being included in society, then it is of primary importance that the technological transition be done without leaving anyone behind (Seifert et al., Reference Seifert, Cotten and Xie2021). In the context of the ongoing pandemic (and beyond), it is incumbent upon all of society to adapt to the unconnected older adult, including ensuring that alternative means of communicating information and providing social interactions are in place (Institut national de santé publique du Québec, 2020; Seifert, Reference Seifert2020). At the same time, all sectors should join forces and be creative in order to facilitate the connection of older adults (e.g., by increasing access to technology training, facilitating access to technical support, or developing technologies that are easier to use and adapted to the different types of disabilities that may be experienced by older adults) (Seifert et al., Reference Seifert, Cotten and Xie2021).

The sub-theme Self-restriction of participation refers to reduced or limited social participation as a result of a deliberate decision by the older adult. Among other things, it was found that some older adults restrict their participation in services or social activities out of fear of stigma and of ageism. It appears that this stigma could come from young people, from society in general, and even from other older adults. Participation restriction related to stigma from other older adults included not feeling welcome and having difficulty fitting into a group. This closely parallels one form of peer bullying among older adults that was reported in the Goodridge, Heal-Salahub, PausJenssen, James, and Lidington (Reference Goodridge, Heal-Salahub, PausJenssen, James and Lidington2017) study, which is not letting someone be part of the group. The authors reported several other types of peer bullying between older adults in their study, including saying mean things behind one’s back, laughing at the person (especially related to physical appearance), and ignoring the person (Goodridge et al., Reference Goodridge, Heal-Salahub, PausJenssen, James and Lidington2017). Elder peer bullying is a phenomenon that has been increasingly studied in recent years but is still not well understood (Leboeuf & Beaulieu, Reference Leboeuf and Beaulieu2021). It would be relevant for future studies to seek to develop ways to reduce elder peer bullying, in order to act on the related social isolation of older adults.

Finally, the sub-theme Low eagerness to socialize is related to a voluntarily withdrawal from social situations by the older adult. Participants mentioned that this situation of low social participation suits the older adults, and when offered ways to enhance their social participation, they may refuse them, echoing Cloutier-Fisher et al.’s (Reference Cloutier-Fisher, Kobayashi and Smith2011) conclusions that social isolation among older adults can be an actively sought state. However, to complement other conclusions of these authors (i.e., that social isolation is embedded in a lifelong preference to be alone), our study highlights that the situation of social isolation in older adults may be the result of a new way of doing things (i.e., reduction in the need to socialize, linked with a gradual habituation to isolation). This comes close to the findings of Couturier and Audy’s (Reference Couturier and Audy2016) qualitative study, which reveals a slow process of consented and desired social disengagement among some isolated older adults. This approach to the social isolation of older adults is not common in the literature. It challenges the dominant paradigm, which is to consider the social isolation of older adults as a state from which they want and must absolutely escape. More work needs to be done to better understand whether there are personal and environmental factors that can lead to this kind of social isolation.

The results of this study highlight the diversity of older adults’ experiences of social isolation; more specifically, that it can be characterized according to two attributes: namely, those of choice and desire regarding low social participation. Given the individuality of the experience of social isolation, intervention approaches must be adapted to each one (Fakoya et al., Reference Fakoya, McCorry and Donnelly2020; Machielse, Reference Machielse2015). In cases in which low social participation is not desired, interventions that aim to provide older adults with the means and opportunities to resume social activities and interactions with people in the community may be the most appropriate (Jopling, Reference Jopling2015). In addition, situations in which low social participation is also not chosen (linked to a form of social exclusion) should be addressed via approaches that aim to act on the social, structural, and political factors specific to older adults’ environments that are likely to generate social isolation (Salma & Salami, Reference Salma and Salami2020; Weldrick & Grenier, Reference Weldrick and Grenier2018). Finally, when low social participation is chosen and desired, it is crucial to incorporate into our approaches a respect for people’s desire to withdraw from social life, while providing them with support opportunities to overcome practical problems that they may encounter in their daily life (e.g., accompaniment to medical appointments or technical support in case of problems with technology), as well as allowing them the opportunity to re-engage when (and if) they need it, with social disengagement not necessarily being an immutable posture (Couturier & Audy, Reference Couturier and Audy2016; Machielse, Reference Machielse2015).

Strengths and Limitations

To discuss the quality of our results and conclusions, we used the standards proposed by Miles et al. (Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2020). The credibility of the results of this study is supported by the involvement of several co-authors with research expertise in the areas of social isolation and aging. Reliability is strengthened by the recruitment that was performed with the help of the members of the operational committee. As a result, we were able to reach participants who had rich and diversified knowledge pertaining to the issue of social isolation among older adults. In particular, through the three focus groups with community stakeholders, people from 11 different institutions who are in contact with or serve the older adult population of Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood participated in the study. Still concerning reliability, R.D.L. (who conducted the qualitative analyses) worked in close collaboration on the analyses with the researcher who facilitated the focus groups and has extensive experience in qualitative methods (M.C.), as well as with two other researchers involved in the project (N.B. and J.F.). Transferability is supported by a detailed description of the setting as well as the participants.

Nevertheless, this study has some limitations. First, we were not able to recruit a large number of very isolated older adults (those who are “hidden” or “invisible”) to participate in the focus groups. However, our key stakeholders provided some insights into how social isolation manifests itself for these older adults. Second, both of our samples were predominantly composed of women. Considering that definitions of social issues are gendered, the male perspective is likely to be under-represented in this study. Third, despite efforts to recruit older adults of different ethnocultural origins, the vast majority of older adult participants considered themselves white, and all were able to speak French. Therefore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to all older adults, or to those in the Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood specifically. Future studies should integrate additional strategies to recruit older adults from diverse ethnocultural backgrounds to explore the phenomenon of social isolation and its components. This would be consistent with the development of a more inclusive society. Finally, because of the sudden occurrence of COVID-19 in Quebec in March 2020, we had to cancel a focus group that had been planned with, among others, representatives of social work, police, and urban planning departments at the municipal level. Meeting with these stakeholders (with different roles and responsibilities than those of the people already met) could have elucidated additional elements regarding the social isolation of older adults in the Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the advance of scientific knowledge about the phenomenon of social isolation among older adults, by exploring the perspective of older adults and representatives of community organizations and municipal services. It highlights that social isolation among older adults can be characterized by deficiencies in social interactions (quantity, function, and quality) as well as by low social participation. In addition, it reveals that the social isolation of older adults may be the result of a deliberate choice and be in fact desired. Those are aspects of social isolation in older adults that are still not well described in the scientific literature. It is imperative to continue research in the area of social isolation among older adults in order to reach a common understanding of this phenomenon. We need to be able to better identify who is experiencing social isolation, while adapting the ways in which we intervene with these individuals, depending on whether or not they are troubled by this situation.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the study participants and members of the operational committee for the time that they devoted and the rich information that they provided.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (#279512, 2020-2023) and by the Université de Montréal (2019 AII-004, 2019-2020). R.D.L. received Master’s Degree scholarships from the Fonds de la recherche du Québec – Santé, the Centre de recherche de l’Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Montréal, and the School of Rehabilitation of Université de Montréal. N.B. is supported by a research scholar award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé. S.B. holds a Canada Research Chair in the cognitive neuroscience of aging and brain plasticity.