Introduction

Dementia has been a pressing public health issue worldwide for several years. The number of people 65 years of age and older living with dementia in Canada nearly doubled from 218,000 in 2002 to 432,000 in 2016 (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019b). More than 80,000 older adults in Canada are diagnosed in a single year (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019b). Age is the greatest risk factor for dementia (Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Sommerlad, Orgeta, Costafreda, Huntley and Ames2017), and although prevalence in Canada is less than 1% in the 65–69 year age group, it is 25% in the 85 and older age group (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018a). If the situation remains unchanged, the number of Canadians living with dementia will continue to increase as life expectancy improves and the share of older adults continues to grow.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted several challenges faced by older adults living with dementia in the community. Dementia increases the risk of exposure to the COVID-19 virus and to negative outcomes such as behavioural changes and delirium (Brown, Kumar, Rajji, Pollock, & Mulsant, Reference Brown, Kumar, Rajji, Pollock and Mulsant2020), thereby increasing the risk of hospitalization in this group (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2020). Unnecessary hospitalizations of people with dementia were already a concern in pre-pandemic Canada, with a hospitalization rate of 33 per 100 versus 20 per 100 people without dementia (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018a). Fear of exposure to the virus and social isolation in hospital prompted families to reconsider the risks and benefits of acute care (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2020). The pandemic also severely affected long-term care (LTC) homes in Canada, where 69% of residents live with dementia (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018a). In the first 3 months of the pandemic, more than 9,000 LTC staff were infected by the virus and 8 in 10 COVID-19 deaths across the country took place in LTC and retirement homes (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2020).

The risk of admission to hospital or LTC for older adults with dementia therefore has serious consequences for this population and the larger Canadian health care system. A care transition refers to a physical move across locations that involves at least one overnight stay (Aaltonen, Rissanen, Forma, Raitanen, & Jylha, Reference Aaltonen, Rissanen, Forma, Raitanen and Jylha2012) or consecutive days of care in different health care settings including home (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Aldridge, Gross, Canavan, Cherlin and Bradley2017). Multiple care transitions are characterized by repeated or multiple moves between two or more care sites, or dynamic movement across multiple sites of care (Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Arling, Wanzhu, Rosenman, Counsell and Stump2012, Reference Callahan, Tu, Unroe, LaMantia, Stump and Clark2015). Care transitions across home, acute, and LTC settings by people living with dementia often result from increasingly complex care needs as function and health progressively decline (Alberta Health, Continuing Care, 2017; Fortinsky & Downs, Reference Fortinsky and Downs2014). In a United States study of older adults, the average number of care transitions between home, hospital, and LTC was two times higher among people with dementia than in those without dementia (Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Tu, Unroe, LaMantia, Stump and Clark2015). Furthermore, Callahan et al. (Reference Callahan, Tu, Unroe, LaMantia, Stump and Clark2015) found that 37% of older adults without dementia experienced no transitions during the observation period, compared with only 4% of individuals with dementia.

Previous reviews of care transitions experienced by persons with dementia have focused primarily on single and isolated moves between care settings (Afram, Verbeek, Bleijlevens, & Hamers, Reference Afram, Verbeek, Bleijlevens and Hamers2015; Dawson, Bowes, Kelly, Velzke, & Ward, Reference Dawson, Bowes, Kelly, Velzke and Ward2015; Hirschman & Hodgson, Reference Hirschman and Hodgson2018; Muller, Lautenschlager, Meyer, & Stephan, Reference Muller, Lautenschlager, Meyer and Stephan2017; Ray, Ingram, & Cohen-Mansfield, Reference Ray, Ingram and Cohen-Mansfield2015). Although multiple transitions have been the subject of two recent reviews, only hospital readmission has been considered (Ma, Bao, Dull, & Wu, Reference Ma, Bao, Dull, Wu and Yu2019; Pickens, Naik, Catic, & Kunik, Reference Pickens, Naik, Catic and Kunik2017).

A care trajectory is defined in this review as a pathway that consists of care transitions across multiple settings. Care trajectories merit attention as they may signal gaps in appropriate community-based care and support, contributing to negative health outcomes for people with dementia and their care partners. Episodes of transition expose individuals to possible medication error (Deeks, Cooper, Draper, Kurrle, & Gibson, Reference Deeks, Cooper, Draper, Kurrle and Gibson2016) and loss of critical information such as advance directives and care plans (Canadian Medical Protective Association, 2018). Care transitions cause disruptions in daily schedules and care continuity that can be particularly stressful and detrimental for those living with dementia, contributing to lower physical and psychological well-being (Ryman et al., Reference Ryman, Erisman, Darvey, Osborne, Swartsenburg and Syurina2019). Negative outcomes for care partners such as stress, depression, and anxiety have also been attributed to care transitions, as well as disrupted self-care caused by a significant shift in focus to the individual with dementia (Sadak, Zdon, Ishado, Zaslavsky, & Borson, Reference Sadak, Zdon, Ishado, Zaslavsky and Borson2017). Emotional concerns and unmet needs for information and support among care partners have been shown to emerge throughout the care transition period; for example, before and after admission to LTC (Afram et al., Reference Afram, Verbeek, Bleijlevens and Hamers2015; Ray et al., Reference Ray, Ingram and Cohen-Mansfield2015).

Although there is agreement that persons with dementia experience numerous transitions, there is less agreement on the standard classification of these transitions (Fortinsky & Downs, Reference Fortinsky and Downs2014). The purpose of this scoping review was to identify and classify care trajectories across multiple settings for people with dementia, and to gain an understanding of the prevalence of multiple transitions and related factors at the individual (demographic and medical) and organizational levels. The current review is intended to increase our knowledge of care trajectories in this population and to inform future research efforts by identifying key gaps in the literature and opportunities for research.

Methods

The review was guided by the Arksey and O’Malley (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) five-stage scoping review methodology and additional steps for each stage as proposed by Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien2010). Further, a review team met biweekly throughout the review process to consider decisions regarding the search strategy, study selection, and data extraction and analysis, as recommended by Levac et al. (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien2010).

Identifying the Research Question

This review aimed to answer the following research questions: What specific care trajectories involving multiple transitions are experienced by people with dementia in terms of care settings, and number and patterns of transitions? What is the prevalence of multiple transitions in this population? What are the factors associated with multiple transitions at the individual (demographic and medical) and organizational levels? For the purpose of this review, multiple transitions were defined as (1) two or more moves between at least three different care settings (e.g., home-hospital-LTC), (2) three or more moves between at least two different care settings that include home (e.g., home-hospital-home-hospital), or (3) two or more moves between two care settings that exclude home (e.g., LTC-hospital-LTC). We anticipated that the findings of this review would identify gaps in current knowledge and point to areas for future research.

Identifying Relevant Studies

A university health sciences librarian (E.W.) developed a comprehensive search strategy in consultation with the first two authors (Supplemental File). Computerized searches of three databases (MEDLINE®, Embase, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL]) were conducted in May, 2017. “Multiple transitions” and “compound transitions” are not commonly used terms, and for this reason our goal was to develop a broad search and manually remove “single transition” studies during study selection. The search was limited to peer-reviewed original research articles, in the English language, published between January 1, 2007 and May 3, 2017. Although the search was not limited to older adults, dementia is more common among older populations, with people 65 years of age and older accounting for approximately 97% of cases (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018a). A 10-year period was chosen for the search, given the increased number of relevant studies in recent years, the pace at which recommendations are being addressed, and to balance the large number of records retrieved.

Study Selection

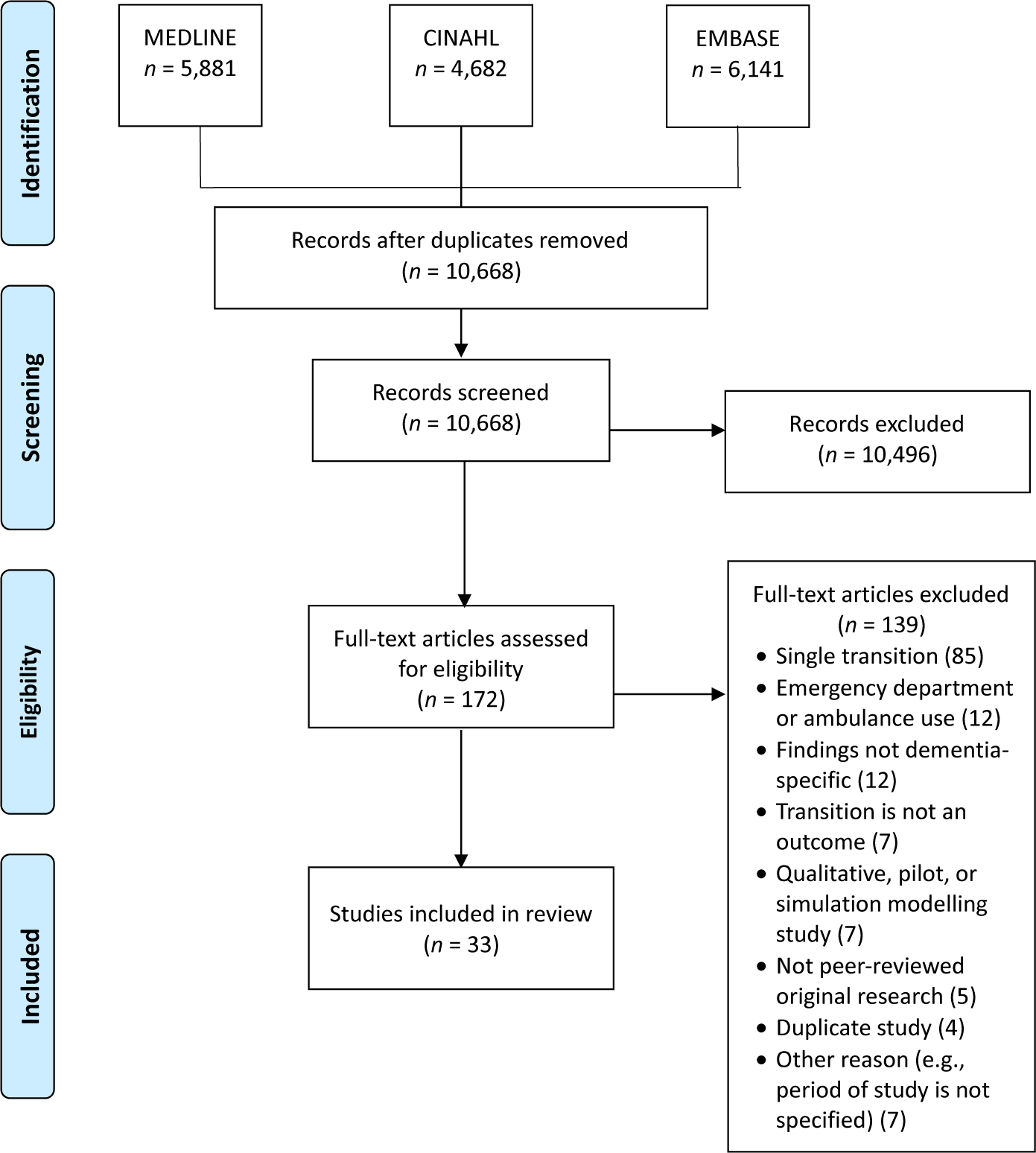

As shown in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram in Figure 1 (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & The PRISMA Group, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009), the search resulted in 16,704 records. This number was reduced to 10,870 after duplicates were removed. The records were exported to a reference program (Endnote) and a web-based systematic review program (DistillerSR), and further de-duplication reduced the number to 10,668 records.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Flow Chart of Study Selection and Inclusion

In the first stage of study selection, four reviewers independently conducted title and abstract relevance screening based on initial inclusion/exclusion criteria. The first author (J.G.K.) screened all titles and abstracts, a second reviewer assessed half, and two additional reviewers each evaluated one quarter of the records. Inter-rater agreement was not calculated, as study selection was an iterative process involving ongoing deliberation among reviewers about the operationalization of “multiple transitions” as defined in the inclusion criteria (Table 1). After excluding 10,496 records, the second stage involved reviewing the full text of 172 articles using a screening form developed by the first author, based on the final inclusion and exclusion criteria. The reviewers first tested the form with 19 articles, and revisions were made based on reviewer feedback. Three reviewers then each independently evaluated the full text of one third of the articles and the first author assessed all articles. Conflicts were resolved by discussion at both stages. The second author (D.G.M.) made the final decision on 5 records when consensus was not possible in the first stage, and consensus was reached between the first author and reviewers on all articles in the second stage. As shown in Figure 1, 33 studies were included in the current review after excluding 139 articles during the second screening stage.

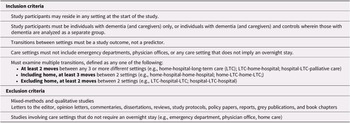

Table 1. Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Charting the Data

The first author extracted the data using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet that was continually refined throughout the abstraction process to adequately capture key data. The following information was extracted from each study, where available: authors and year of publication; study country and setting, objectives, design, timeframe and study period, intervention, outcome measures, sample characteristics [age at baseline, sex, ethnicity, residence (e.g., rural, live at home or in long-term care), method of dementia identification such as clinical diagnosis, timing of dementia identification such as before first transition, proportion of patients with dementia and type of dementia, and proportion of patients with other medical conditions]; transitions as a primary focus (yes/no); and study conclusions, key implications and recommendations, and reported limitations. Data charting also included identifying and extracting care trajectories based on transition patterns that involved two moves, three moves, or four or more moves across settings, the prevalence of transitions, and factors associated with transitions at the individual (demographic and medical) and organizational levels. In addition, length of stay in hospital was documented where applicable. Some studies reported more than one trajectory, and data relevant to all routes were extracted where this was the case.

Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

The data extracted to Microsoft Excel were collated in a series of Microsoft Word tables (not included here) as an intermediate step, and study characteristics were organized in a numerical summary (Table 2). A framework of care trajectories was developed based on transition patterns extracted at the charting stage (Figure 2). This framework classifies trajectories based on starting location and other settings involved, number of transitions, and the pattern of movement across locations. For the purpose of this review, trajectories that began in an unspecified location or in hospital were considered to originate in location ‘x’. We rationalized that hospitalization constitutes a temporary stay for individuals who have other permanent or long-stay living arrangements. In transitions that involved multiple unspecified locations, ‘x’ was counted as a single location.

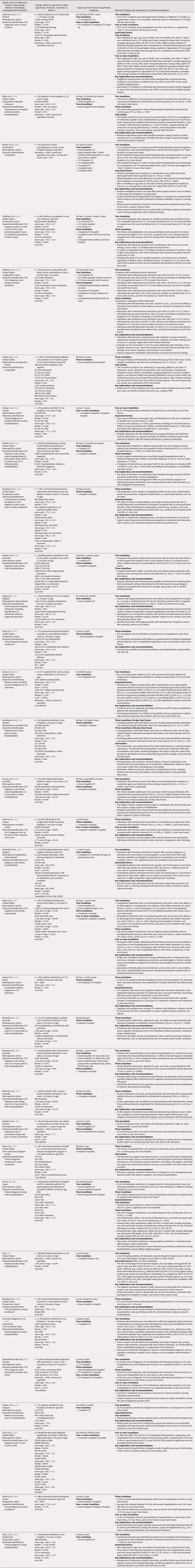

Figure 2. Twenty-Six Care Trajectories Identified in Included Studies (n = 33)

1 Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Chippendale, Resnick and Galvin2015; Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016; Fogg, et al., Reference Fogg, Meredith, Bridges, Gould and Griffiths2017; Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Mitchell, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Mondor et al., Reference Mondor, Maxwell, Hogan, Bronskill, Gruneir and Lane2017; Ono et al., Reference Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi and Tamai2011; Zekry et al., Reference Zekry, Herrmann, Grandjean, Vitale, De Pinho and Michel2009

2 Ono et al., Reference Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi and Tamai2011

3 Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017

4 Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016

5 Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Chippendale, Resnick and Galvin2015; Cassel et al., Reference Cassel, Kerr, McClish, Skoro, Johnson and Wanke2016; Mondor et al., Reference Mondor, Maxwell, Hogan, Bronskill, Gruneir and Lane2017; Ono et al., Reference Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi and Tamai2011; Sivananthan & McGrail, Reference Sivananthan and McGrail2016

6 Fong et al., Reference Fong, Jones, Marcantonio, Tommet, Gross and Habtemariam2012; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Zanin, Jones, Marcantonio, Fong and Yang2010; Voisin, Sourdet, Cantet, Andrieu, & Vellas, Reference Voisin, Sourdet, Cantet, Andrieu and Vellas2009

7 Voisin et al., Reference Voisin, Sourdet, Cantet, Andrieu and Vellas2009

8 Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Arling, Wanzhu, Rosenman, Counsell and Stump2012

9 Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Arling, Wanzhu, Rosenman, Counsell and Stump2012; Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Tu, Unroe, LaMantia, Stump and Clark2015

10 Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016; Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Arling, Wanzhu, Rosenman, Counsell and Stump2012; Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Tu, Unroe, LaMantia, Stump and Clark2015

11 Aaltonen et al., Reference Aaltonen, Raitanen, Forma, Pulkki, Rissanen and Jylha2014; Givens et al., Reference Givens, Mitchell, Kuo, Gozalo, Mor and Teno2013

12 Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016

13 Sivananthan & McGrail, Reference Sivananthan and McGrail2016

14 Leung, Kwan, & Chi, Reference Leung, Kwan and Chi2013; Sivananthan & McGrail, Reference Sivananthan and McGrail2016

15 Sivananthan & McGrail, Reference Sivananthan and McGrail2016

16 Aaltonen et al., Reference Aaltonen, Raitanen, Forma, Pulkki, Rissanen and Jylha2014

17 Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016; Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield, & Gravenstein, Reference Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield and Gravenstein2014; Draper, Karmel, Gibson, Peut, & Anderson, Reference Draper, Karmel, Gibson, Peut and Anderson2011; Kasteridis et al., Reference Kasteridis, Mason, Goddard, Jacobs, Santos and Rodriguez-Sanchez2016; Seematter-Bagnoud, Martin, & Bula, Reference Seematter-Bagnoud, Martin and Bula2012; Takacs, Ungvari, & Gazdag, Reference Takacs, Ungvari and Gazdag2015

18 Oud et al., Reference Oud2017

19 Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016

20 Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016

21 Daiello et al., Reference Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield and Gravenstein2014; Davydow et al., Reference Davydow, Zivin, Katon, Pontone, Chwastiak and Langa2014; Draper et al., Reference Draper, Karmel, Gibson, Peut and Anderson2011; Gustafsson et al., Reference Gustafsson, Sjolander, Pfister, Jonsson, Schneede and Lovheim2017; Harvey et al., Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2015; Hsiao et al., Reference Hsiao, Peng, Wen, Liang, Wang and Chen2015; Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2015, Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016, Reference Mitchell, Draper, Harvey, Brodaty and Close2017; Noel et al., Reference Noel, Kaluzynski and Templeton2017

22 Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Arling, Wanzhu, Rosenman, Counsell and Stump2012, Reference Callahan, Tu, Unroe, LaMantia, Stump and Clark2015

23 Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Arling, Wanzhu, Rosenman, Counsell and Stump2012, Reference Callahan, Tu, Unroe, LaMantia, Stump and Clark2015

24 Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Tu, Unroe, LaMantia, Stump and Clark2015

25 Hsiao et al., Reference Hsiao, Peng, Wen, Liang, Wang and Chen2015; Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017; Teno et al., Reference Teno, Gozalo, Bynum, Leland, Miller and Morden2013

26 Chang et al., Reference Chang, Lin, Chang, Chen, Huang and Lui2015

x = unspecified location

Note: Bolded trajectories were examined in three or more studies. More than one trajectory was reported in 14 studies (Aaltonen et al., Reference Aaltonen, Raitanen, Forma, Pulkki, Rissanen and Jylha2014; Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Chippendale, Resnick and Galvin2015; Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Arling, Wanzhu, Rosenman, Counsell and Stump2012, Reference Callahan, Tu, Unroe, LaMantia, Stump and Clark2015; Daiello et al., Reference Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield and Gravenstein2014; Draper et al., Reference Draper, Karmel, Gibson, Peut and Anderson2011; Harvey et al., Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2015; Hsiao et al., Reference Hsiao, Peng, Wen, Liang, Wang and Chen2015; Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Mondor et al., Reference Mondor, Maxwell, Hogan, Bronskill, Gruneir and Lane2017; Ono et al., Reference Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi and Tamai2011; Sivananthan & McGrail, Reference Sivananthan and McGrail2016; Voisin et al., Reference Voisin, Sourdet, Cantet, Andrieu and Vellas2009).

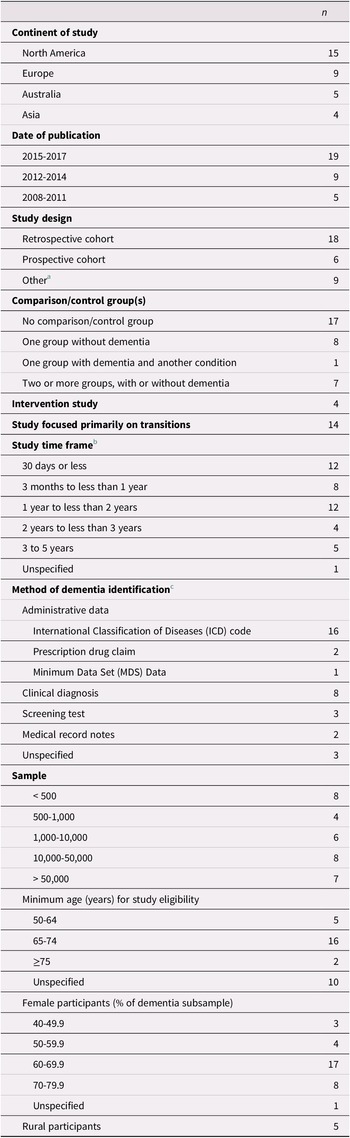

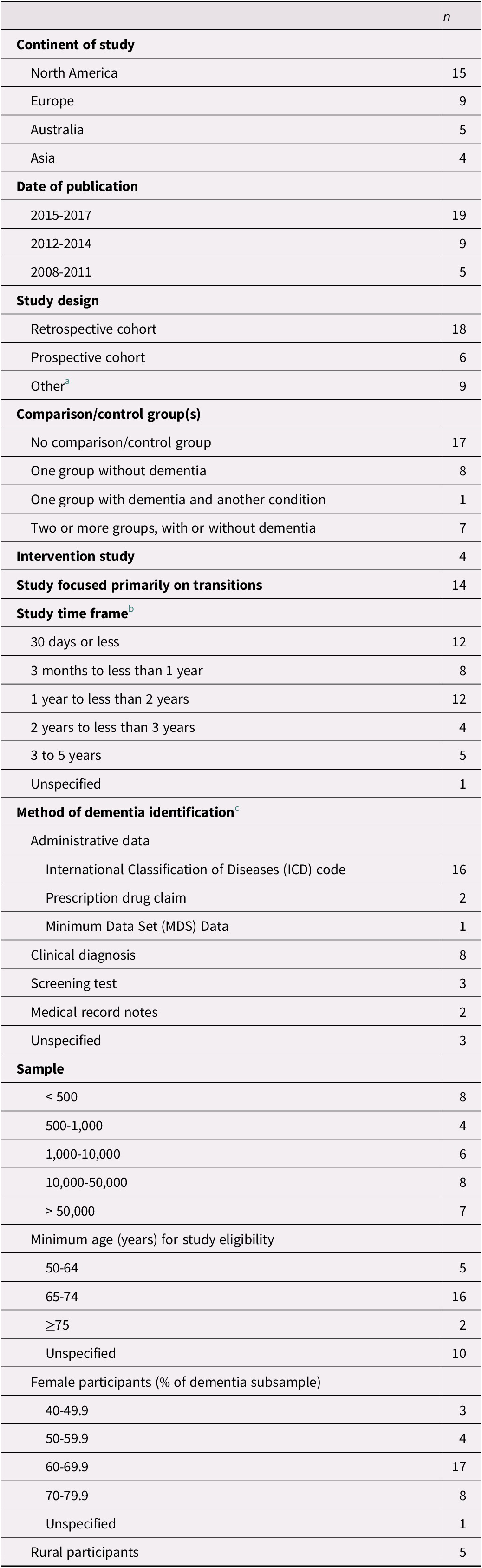

Table 2. Study characteristics (n = 33)

Note.

a Other study designs included chart audit and caregiver survey; comparative repeated measures; cross-sectional; longitudinal cohort; observational cohort; randomized controlled trial; retrospective longitudinal observational; retrospective observational; and retrospective survey.

b Multiple time frames were included in 9 studies (Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Chippendale, Resnick and Galvin2015; Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Arling, Wanzhu, Rosenman, Counsell and Stump2012; Daiello et al., Reference Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield and Gravenstein2014; Draper et al., Reference Draper, Karmel, Gibson, Peut and Anderson2011; Gustafsson et al., Reference Gustafsson, Sjolander, Pfister, Jonsson, Schneede and Lovheim2017; Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Mitchell, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017; Leung et al., Reference Leung, Kwan and Chi2013; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016).

c Two studies used multiple methods of identification (Daiello et al., Reference Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield and Gravenstein2014; Mondor et al., Reference Mondor, Maxwell, Hogan, Bronskill, Gruneir and Lane2017).

The main findings in the narrative synthesis centre on the most commonly reported trajectories (as examined in three or more included studies), prevalence of transitions, and factors associated with transitions. Table 3 summarizes the relevant findings including all identified care trajectories, prevalence of transitions, associated factors, and key implications and recommendations.

Table 3. Summary of included studies (n = 33)

Note. index hospitalization = admission to the first hospital in the care trajectory; AD = Alzheimer’s disease; AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; LTC = long-term care; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; PRD = Parkinsonism-related dementia; SD = standard deviation; VaD = vascular dementia.

Results

Study Characteristics

Characteristics of the 33 included studies are provided in Table 2. The majority of articles were published since 2015, and most studies were conducted in North America or Europe. Four studies included an intervention (Boltz, Chippendale, Resnick, & Galvin, Reference Boltz, Chippendale, Resnick and Galvin2015; Cassel et al., Reference Cassel, Kerr, McClish, Skoro, Johnson and Wanke2016; Gustafsson et al., Reference Gustafsson, Sjolander, Pfister, Jonsson, Schneede and Lovheim2017; Noel, Kaluzynski, & Templeton, Reference Noel, Kaluzynski and Templeton2017). All of the studies included a mixed-sex sample, with females accounting for at least 60% of the dementia sample in three quarters of the studies.

Most studies assessed the effect of dementia on the use and outcomes of health services in general, of which transitions across care settings were only one component. Time frames considered in the studies ranged from less than 30 days to 5 years, with short time frames of less than 1 year examined most frequently. Few studies focused on time frames of 3 years or longer (Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten, & Morin, Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016; Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Arling, Wanzhu, Rosenman, Counsell and Stump2012; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Lin, Chang, Chen, Huang and Lui2015; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Zanin, Jones, Marcantonio, Fong and Yang2010; Seematter-Bagnoud, Martin, & Bula, Reference Seematter-Bagnoud, Martin and Bula2012).

Individuals with dementia were identified on the basis of administrative data in the majority of studies. In these studies, diagnosis was recorded from the data either directly after the first transition had occurred (Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield, & Gravenstein, Reference Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield and Gravenstein2014; Draper, Karmel, Gibson, Peut, & Anderson, Reference Draper, Karmel, Gibson, Peut and Anderson2011; Harvey, Mitchell, Brodaty, Draper, & Close, Reference Harvey, Mitchell, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Kasteridis et al., Reference Kasteridis, Mason, Goddard, Jacobs, Santos and Rodriguez-Sanchez2016; Oud, Reference Oud2017; Zekry et al., Reference Zekry, Herrmann, Grandjean, Vitale, De Pinho and Michel2009) or up to 1 year prior to the first transition (Davydow et al., Reference Davydow, Zivin, Katon, Pontone, Chwastiak and Langa2014; Givens et al., Reference Givens, Mitchell, Kuo, Gozalo, Mor and Teno2013; Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Mitchell, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2015; Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper, & Close, Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016, 2017). Nevertheless, prevalent and incident cases were not differentiated in these studies, and the time since diagnosis was not provided. Only four studies, all based on administrative data, explicitly identified participants with incident (Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Arling, Wanzhu, Rosenman, Counsell and Stump2012, Reference Callahan, Tu, Unroe, LaMantia, Stump and Clark2015; Hsiao et al., Reference Hsiao, Peng, Wen, Liang, Wang and Chen2015; Sivananthan & McGrail, Reference Sivananthan and McGrail2016) or prevalent dementia (Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Arling, Wanzhu, Rosenman, Counsell and Stump2012). Other studies relied mainly on clinical diagnoses or screening tests for identification purposes, often diagnosing or assessing participants either directly after the first transition (Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Chippendale, Resnick and Galvin2015; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Lin, Chang, Chen, Huang and Lui2015; Fogg, Meredith, Bridges, Gould, & Griffiths, Reference Fogg, Meredith, Bridges, Gould and Griffiths2017; Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi, & Tamai, Reference Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi and Tamai2011; Seematter-Bagnoud et al., Reference Seematter-Bagnoud, Martin and Bula2012) or at study enrollment before the first transition occurred (Davydow et al., Reference Davydow, Zivin, Katon, Pontone, Chwastiak and Langa2014; Fong et al., Reference Fong, Jones, Marcantonio, Tommet, Gross and Habtemariam2012; Noel et al., Reference Noel, Kaluzynski and Templeton2017; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Zanin, Jones, Marcantonio, Fong and Yang2010; Voisin, Sourdet, Cantet, Andrieu, & Vellas, Reference Voisin, Sourdet, Cantet, Andrieu and Vellas2009). In these studies, it is possible that some participants were previously diagnosed with dementia. In studies with long observation periods in which dementia had been diagnosed at enrollment, it is also possible that some participants had been living with dementia for some time before their first transition.

Prevalence of Transitions and Trajectories

We identified 26 distinct care trajectories experienced by individuals with dementia, based on the starting location of the trajectory and care settings involved, transition pattern, and number of transitions experienced (Figure 2 and Table 3). In most trajectories, the first transition involved hospitalization (n = 24); in two trajectories, the first transition was from LTC to home. Considering all 26 trajectories, the destination of the second transition was LTC in 10 trajectories, home or other location in 6, unspecified in 6, hospice care in 2 and hospital in 2 trajectories.

Described subsequently and organized by starting location are the seven most common trajectories, defined as those that were each examined in three or more of the included studies. These trajectories were examined in a total of 26 of the included studies. Included is the prevalence of each trajectory or the prevalence of specific transitions within the trajectories, as reported in the studies.

From home

The most common care trajectory beginning from home and involving multiple settings, as evaluated in nine studies, ended in transition to LTC after a hospitalization (home-hospital-LTC) (Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Chippendale, Resnick and Galvin2015; Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016; Fogg et al., Reference Fogg, Meredith, Bridges, Gould and Griffiths2017; Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Mitchell, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Kedia, Chavan, Boop, & Yu, Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Mondor et al., Reference Mondor, Maxwell, Hogan, Bronskill, Gruneir and Lane2017; Ono et al., Reference Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi and Tamai2011; Zekry et al., Reference Zekry, Herrmann, Grandjean, Vitale, De Pinho and Michel2009). Eight of the studies considered timeframes of 1–3.5 years, finding that 16.3 to 58.4 per cent of individuals with dementia admitted to hospital from home transitioned to LTC (Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Chippendale, Resnick and Galvin2015; Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016; Fogg et al., Reference Fogg, Meredith, Bridges, Gould and Griffiths2017; Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Mondor et al., Reference Mondor, Maxwell, Hogan, Bronskill, Gruneir and Lane2017; Ono et al., Reference Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi and Tamai2011; Zekry et al., Reference Zekry, Herrmann, Grandjean, Vitale, De Pinho and Michel2009). One study found that 25.3 per cent of patients with dementia admitted to hospital with an injury in New South Wales were discharged to LTC; however, it did not specify the time frame (Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Mitchell, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016). Five studies included controls, and all found that hospitalized individuals with dementia were more likely to be discharged to LTC than people without dementia (16.3–35.9% vs. 3.5–8.6%) over time frames of 1–2 years (Fogg et al., Reference Fogg, Meredith, Bridges, Gould and Griffiths2017; Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Mitchell, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Zekry et al., Reference Zekry, Herrmann, Grandjean, Vitale, De Pinho and Michel2009).

Reported in five articles, the second common trajectory that originated from home was characterized by hospitalization followed by re-hospitalization from home (home-hospital-home-hospital) (Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Chippendale, Resnick and Galvin2015; Cassel et al., Reference Cassel, Kerr, McClish, Skoro, Johnson and Wanke2016; Mondor et al., Reference Mondor, Maxwell, Hogan, Bronskill, Gruneir and Lane2017; Ono et al., Reference Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi and Tamai2011; Sivananthan & McGrail, Reference Sivananthan and McGrail2016). Ono et al. (Reference Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi and Tamai2011) reported in a retrospective cohort study conducted in one hospital in Japan, that 23.3 per cent of patients first admitted to a ward for behavioural and psychological symptoms related to dementia, were readmitted to the same ward within 2 years. In a large retrospective cohort study of home care clients with dementia in one Canadian province, Mondor et al. (Reference Mondor, Maxwell, Hogan, Bronskill, Gruneir and Lane2017) reported that 13.5 per cent of all clients experienced two or more hospital admissions within 1 year. A separate retrospective cohort study in another Canadian province further demonstrated that 20 per cent of community-based individuals experienced two or more hospital admissions in 1 year; specifically, in the first year of the dementia diagnosis (Sivananthan & McGrail, Reference Sivananthan and McGrail2016). Two separate intervention studies reported a reduction in hospital readmission rates among patients with dementia in an intervention group compared with a control group (Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Chippendale, Resnick and Galvin2015; Cassel et al., Reference Cassel, Kerr, McClish, Skoro, Johnson and Wanke2016). In the first study, conducted in two United States hospitals, Boltz et al. (Reference Boltz, Chippendale, Resnick and Galvin2015) found a lower 30-day hospital readmission rate among patients with dementia in the intervention compared with the control group (7% vs. 24%). Whereas the control group received staff education only, the intervention group was exposed to multiple elements: staff received family-centred education, ongoing training, and motivation; environmental and policy modifications were made, such as the addition of bedside white boards to increase communication between staff and patient/family; and patient/family education encouraged engagement in developing and communicating individualized goals and expectations. Similarly, the second study found that patients with dementia in a U.S. state who participated in a specialty palliative care program intervention had a lower rate of 30-day hospital readmission than non-participants (11% vs. 35%) (Cassel et al., Reference Cassel, Kerr, McClish, Skoro, Johnson and Wanke2016).

The third common trajectory that started from home, which was investigated in three studies, involved a first hospitalization followed by readmission from an unspecified location (home-hospital-x-hospital) (Fong et al., Reference Fong, Jones, Marcantonio, Tommet, Gross and Habtemariam2012; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Zanin, Jones, Marcantonio, Fong and Yang2010; Voisin et al., Reference Voisin, Sourdet, Cantet, Andrieu and Vellas2009). Fong et al. (Reference Fong, Jones, Marcantonio, Tommet, Gross and Habtemariam2012) considered participants of a specialized US research centre with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) residing at home in the community and admitted to hospital, finding that 61 per cent were readmitted to hospital within 1 year. Two articles reported the number of times that community-based individuals with AD were admitted to hospital, with Rudolph et al. (Reference Rudolph, Zanin, Jones, Marcantonio, Fong and Yang2010) finding that 47 per cent of patients attending a community-based United States research centre were admitted to hospital two or more times over an average of 4 years, and Voisin et al. (Reference Voisin, Sourdet, Cantet, Andrieu and Vellas2009) finding that 19.8 per cent of participants of a prospective cohort study nationwide in France were hospitalized two times over 2 years.

From LTC

As investigated in five articles, the trajectory originating from LTC that was most often studied involved transfer to hospital and back to LTC (Aaltonen et al., Reference Aaltonen, Raitanen, Forma, Pulkki, Rissanen and Jylha2014; Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016; Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Arling, Wanzhu, Rosenman, Counsell and Stump2012, Reference Callahan, Tu, Unroe, LaMantia, Stump and Clark2015; Givens et al., Reference Givens, Mitchell, Kuo, Gozalo, Mor and Teno2013). Regarding this LTC-hospital-LTC route, Bucher et al. (Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016) reported that 91 per cent of people with dementia living in Swiss nursing homes before hospitalization were discharged to LTC over 3.5 years. Callahan et al. (Reference Callahan, Arling, Wanzhu, Rosenman, Counsell and Stump2012) observed that 20 per cent of primary care patients with dementia in a U.S. state were admitted from LTC to hospital and later discharged back to LTC over an average 5-year time frame. In a later study using national data from the United States Health and Retirement study, Callahan et al. (Reference Callahan, Tu, Unroe, LaMantia, Stump and Clark2015) reported that individuals with dementia compared with those without were more likely to experience this route over a 12-month time frame, regardless of the stage of dementia.

From an unspecified location

Detailed in 11 articles, the most common trajectory beginning from an unspecified setting involved hospital admission and readmission (x-hospital-x-hospital) (Daiello et al., Reference Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield and Gravenstein2014; Davydow et al., Reference Davydow, Zivin, Katon, Pontone, Chwastiak and Langa2014; Draper et al., Reference Draper, Karmel, Gibson, Peut and Anderson2011; Gustafsson et al., Reference Gustafsson, Sjolander, Pfister, Jonsson, Schneede and Lovheim2017; Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Mitchell, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Hsiao et al., Reference Hsiao, Peng, Wen, Liang, Wang and Chen2015; Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2015, Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016, 2017; Noel et al., Reference Noel, Kaluzynski and Templeton2017). Two of the 11 articles did not report hospital readmission rates at the patient level (Daiello et al., Reference Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield and Gravenstein2014; Davydow et al., Reference Davydow, Zivin, Katon, Pontone, Chwastiak and Langa2014); however, 30-day readmission was found to be associated with dementia by Daiello et al. (Reference Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield and Gravenstein2014). A further two studies examined the effectiveness of separate interventions (Gustafsson et al., Reference Gustafsson, Sjolander, Pfister, Jonsson, Schneede and Lovheim2017; Noel et al., Reference Noel, Kaluzynski and Templeton2017). In a randomized controlled trial of patients with dementia admitted to two hospitals in Sweden, Gustafsson et al. (Reference Gustafsson, Sjolander, Pfister, Jonsson, Schneede and Lovheim2017) determined that patients with dementia without heart failure receiving a medication reconciliation intervention exhibited a lower rate of drug-related readmission over a 6-month time frame than non-intervention patients (11% vs. 20%). Noel et al. (Reference Noel, Kaluzynski and Templeton2017) found a 30-day readmission rate of 5 per cent among community-based patients with dementia and care partners receiving care management; however, a group for comparison was not included. The remaining seven studies included controls without dementia. Draper et al. (Reference Draper, Karmel, Gibson, Peut and Anderson2011) reported a higher readmission rate among patients with dementia than controls in a 3-month time frame (40% vs. 32%) and Hsiao et al. (Reference Hsiao, Peng, Wen, Liang, Wang and Chen2015) found 4.4 per cent of persons with dementia compared with 1.4 per cent of controls were admitted to hospital two times within 1 year in a national study of Taiwan (Hsiao et al., Reference Hsiao, Peng, Wen, Liang, Wang and Chen2015). Over time frames of 28 to 30 days, two studies identified higher readmission rates among patients with dementia (18.9–35.2%) than controls (9.8–23.3%) (Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Draper, Harvey, Brodaty and Close2017) and three studies found lower or no difference in rates among patients with dementia (13.8–21%) compared with controls (17.5–24.4%) (Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Mitchell, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2015, Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016).

Reported in six articles, trajectories characterized by hospital admission from an unspecified setting followed by transition to LTC (x-hospital-LTC) (Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016; Daiello et al., Reference Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield and Gravenstein2014; Draper et al., Reference Draper, Karmel, Gibson, Peut and Anderson2011; Kasteridis et al., Reference Kasteridis, Mason, Goddard, Jacobs, Santos and Rodriguez-Sanchez2016; Seematter-Bagnoud et al., Reference Seematter-Bagnoud, Martin and Bula2012; Takacs, Ungvari, & Gazdag, Reference Takacs, Ungvari and Gazdag2015) were also common. The proportion of individuals with dementia admitted to hospital from an unspecified location who transitioned to LTC ranged from 19 to 50 per cent within time frames of 3 months to 3.5 years (Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016; Kasteridis et al., Reference Kasteridis, Mason, Goddard, Jacobs, Santos and Rodriguez-Sanchez2016; Seematter-Bagnoud et al., Reference Seematter-Bagnoud, Martin and Bula2012; Takacs et al., Reference Takacs, Ungvari and Gazdag2015). Significant differences were found in all of the studies that included control patients (Daiello et al., Reference Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield and Gravenstein2014; Draper et al., Reference Draper, Karmel, Gibson, Peut and Anderson2011; Seematter-Bagnoud et al., Reference Seematter-Bagnoud, Martin and Bula2012). Draper et al. (Reference Draper, Karmel, Gibson, Peut and Anderson2011) determined that patients with dementia admitted to hospital in one Australian state were more likely to transfer to LTC than to their usual residence over a 2-year time frame, than were hospitalized patients without dementia. Hospitalized patients with dementia were more likely than those without dementia to be discharged to a nursing home from post-acute rehabilitation in a Swiss hospital over a 3-year time frame (28.8% vs. 4.2%) (Seematter-Bagnoud et al., Reference Seematter-Bagnoud, Martin and Bula2012). Further, in a study of hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries in one U.S. state, Daiello et al. (Reference Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield and Gravenstein2014) revealed that hospitalizations among patients with dementia compared with those among controls were more likely to result in discharge to LTC over 1 year (51.5% vs. 21.6% of hospitalizations).

Examined in three studies, the final common trajectory originated in an unspecified location and consisted of more than four transitions [x-hospital-x-hospital-x-hospital] (Hsiao et al., Reference Hsiao, Peng, Wen, Liang, Wang and Chen2015; Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017; Teno et al., Reference Teno, Gozalo, Bynum, Leland, Miller and Morden2013). Significant differences were found in the studies that included control patients (Hsiao et al., Reference Hsiao, Peng, Wen, Liang, Wang and Chen2015; Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017). In two separate studies, each with a 1-year time frame, 2.2 per cent of individuals with dementia compared with 0.6 per cent of controls experienced three admissions in a national study of Taiwan (Hsiao et al., Reference Hsiao, Peng, Wen, Liang, Wang and Chen2015), and 19.9 per cent of individuals with dementia and concurrent cancer across three U.S. states experienced three or more hospitalizations compared with 1.6 per cent with neither dementia nor cancer (Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017). In a third study using United States national data, 10.7 to 12 per cent of individuals with dementia in the last 90 days of life underwent three or more hospital admissions compared with 13.2 to 19.9 per cent of those with cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): however, significance testing was not provided (Teno et al., Reference Teno, Gozalo, Bynum, Leland, Miller and Morden2013).

Factors Associated with Transitions and Trajectories

Eleven studies overall examined factors associated with transitions or care trajectories as a whole among individuals with dementia, with two of these studies examining variables related to more than one transition or trajectory (Aaltonen et al., Reference Aaltonen, Raitanen, Forma, Pulkki, Rissanen and Jylha2014; Ono et al., Reference Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi and Tamai2011). Factors examined in each study are summarized in Table 3. Individual demographic and medical characteristics were the main focus in most studies, and both types of characteristics were examined in relation to re-hospitalization, repeated hospitalization, transition from hospital to hospice care, and transition from hospital to LTC. Organizational variables were examined in relation only to transition from hospital to LTC, and with respect to a trajectory that involved residence in two different LTC homes before and after hospitalization.

In terms of medical characteristics examined in eight studies, co-morbid dementia and depression were associated with greater odds of 30-day re-hospitalization from an unspecified location (Davydow et al., Reference Davydow, Zivin, Katon, Pontone, Chwastiak and Langa2014). More severe cognitive impairment and increased medication use (Leung, Kwan, & Chi, Reference Leung, Kwan and Chi2013) increased the likelihood of re-hospitalization from LTC. Several medical factors were associated with hospitalization four or more times within 4 years of initial admission (repeated hospitalization), namely coronary artery disease, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and fall-related fracture recorded at index admission (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Lin, Chang, Chen, Huang and Lui2015). Medical characteristics related to transition from hospital to hospice care included chronic co-morbidity, failing organs, and mechanical ventilation (Oud, Reference Oud2017). Medical factors also increased the risk of transition from hospital to LTC in four studies, and included severe medical issues (Takacs et al., Reference Takacs, Ungvari and Gazdag2015); poor functional status and severe dementia (Zekry et al., Reference Zekry, Herrmann, Grandjean, Vitale, De Pinho and Michel2009); a higher number of co-morbidities, incontinence, falls, hip fracture, cerebrovascular disease, and cancer (Kasteridis et al., Reference Kasteridis, Mason, Goddard, Jacobs, Santos and Rodriguez-Sanchez2016); and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube insertion in hospital, greater functional ability, and diabetes (Givens et al., Reference Givens, Mitchell, Kuo, Gozalo, Mor and Teno2013).

Demographic factors examined in relation to care transitions in four studies mainly centred on age and sex; however, other variables were also considered. Ono et al. (Reference Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi and Tamai2011) found sex differences in early re-hospitalization from home within 3 months of discharge from a hospital ward for patients with dementia. Ono et al. reported that having fewer cohabitants predicted readmission among males but not females, and that a longer stay in the index hospital predicted readmission among females but not males. Another study reported that the likelihood of three or more hospitalizations (repeated hospitalization) among LTC residents increased for those who were younger and male (Aaltonen et al., Reference Aaltonen, Raitanen, Forma, Pulkki, Rissanen and Jylha2014). Demographics related to transition from hospital to hospice care included older age, “white” ethnicity, and lack of health insurance (Oud, Reference Oud2017). Several demographic characteristics were associated with a higher risk of transition from hospital to LTC, including female sex (Kasteridis et al., Reference Kasteridis, Mason, Goddard, Jacobs, Santos and Rodriguez-Sanchez2016; Ono et al., Reference Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi and Tamai2011), male sex (Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016), older age (Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016; Kasteridis et al., Reference Kasteridis, Mason, Goddard, Jacobs, Santos and Rodriguez-Sanchez2016), and widowed marital status (Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016). Patient demographics associated with a lower risk of transition from hospital to LTC included living in areas with a higher rate of unpaid care provision (50 or more hours/week) and a higher proportion of guaranteed pension recipients (Kasteridis et al., Reference Kasteridis, Mason, Goddard, Jacobs, Santos and Rodriguez-Sanchez2016). In examining the LTC1-hospital-LTC2 trajectory, Aaltonen et al. (Reference Aaltonen, Raitanen, Forma, Pulkki, Rissanen and Jylha2014) found a relationship between younger age and residence in two different LTC homes pre-post hospitalization in the last 90 days of life.

Two studies also identified variables associated with care trajectories at the organizational level. The first study found that nursing home characteristics were associated with transition of residents from hospital to a skilled nursing facility, specifically large size (more than 100 beds), corporate chain status, for-profit structure, and urban versus rural location (Givens et al., Reference Givens, Mitchell, Kuo, Gozalo, Mor and Teno2013). The second study identified that living in sheltered housing or a specialized LTC versus a traditional nursing home was associated with residence in two different LTC homes pre-post hospitalization in the last 90 days of life (Aaltonen et al., Reference Aaltonen, Raitanen, Forma, Pulkki, Rissanen and Jylha2014).

Discussion

This scoping review identified and classified care trajectories across multiple settings among people with dementia, and investigated the prevalence of multiple transitions and factors associated with transitions. We identified 26 distinct trajectories, including 7 trajectories that were each investigated in three or more studies and considered to be common pathways for the purpose of this review. Trajectories that involved either hospital readmission or discharge from hospital to LTC were most common. Dementia increased the likelihood of a single transition from hospital to LTC as well as hospital readmission. Factors associated with particular transitions were identified mainly at the individual level of medical and demographic characteristics. Complex care trajectories that involved numerous transitions over the course of several years were not typically considered in the studies, suggesting opportunities for future investigation.

Four of the most common trajectories involved three or more transitions consisting of hospital readmission with initial admission from home or an unspecified setting. In studies in which the overall trajectory was considered, prevalence ranged from 4.4 to 19.8 per cent for two admissions within 1–2 years (Hsiao et al., Reference Hsiao, Peng, Wen, Liang, Wang and Chen2015; Voisin et al., Reference Voisin, Sourdet, Cantet, Andrieu and Vellas2009) and from 10.7 to 19.9 per cent for three or more admissions within 90 days to 1 year (Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017; Teno et al., Reference Teno, Gozalo, Bynum, Leland, Miller and Morden2013). Variations across studies may be partly the result of differences in time frames and variations in health care systems across countries. Although studies with longer timeframes of 3 months to 1 year found that patients with dementia were more likely to be re-hospitalized than were controls (Draper et al., Reference Draper, Karmel, Gibson, Peut and Anderson2011; Hsiao et al., Reference Hsiao, Peng, Wen, Liang, Wang and Chen2015; Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017), studies with shorter periods of 28–30 days found mixed results (Daiello et al., Reference Daiello, Gardner, Epstein-Lubow, Butterfield and Gravenstein2014; Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Mitchell, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2015, Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016, 2017). These findings suggest a need to improve post-discharge care management for persons with dementia (Lin, Zhong, Fillit, Cohen, & Neumann, Reference Lin, Zhong, Fillit, Cohen and Neumann2017) and a greater role for primary health care providers and community care providers in coordinating management (Austrom, Boustani, & LaMantia, Reference Austrom, Boustani and LaMantia2018).

This review found that re-hospitalization factors were identified mainly in terms of medical and demographic characteristics. Previous research suggests that readmission risk may be reduced by effective discharge planning and provision of home health services after discharge, particularly for those who live alone (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Zhong, Fillit, Cohen and Neumann2017). Specifically for persons in LTC, Leung et al. (Reference Leung, Kwan and Chi2013) found that re-hospitalization risk increased with more severe cognitive impairment and medication use. Nearly half of all older adults living in LTC in Canada are prescribed at least 10 different drugs (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018b); however, awareness of the need to de-prescribe for older adults with dementia is growing among health care providers (Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement, 2019).

Three other common trajectories involved two transitions consisting of discharge from hospital to LTC in the second transition. Among people with dementia living at home before hospitalization, the prevalence of a second transition to LTC ranged from 16 to 36 per cent compared with less than 9 per cent for those without dementia, over periods of 1–2 years (Fogg et al., Reference Fogg, Meredith, Bridges, Gould and Griffiths2017; Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Mitchell, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Kedia et al., Reference Kedia, Chavan, Boop and Yu2017; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Harvey, Brodaty, Draper and Close2016; Zekry et al., Reference Zekry, Herrmann, Grandjean, Vitale, De Pinho and Michel2009). Included studies suggested that transition from hospital to LTC may follow from interactions among the cause of hospitalization, pre-existing conditions including cognitive and functional impairment, and the hospitalization experience itself. Cognitive impairment, physical assistance needs, and assessment for LTC admission performed in hospital are factors shown in prior research to increase the odds of admission to LTC (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2017).

Several medical and demographic characteristics were also found to be associated with a single transition from hospital to LTC. Demographic factors included widowhood (Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016), older age (Bucher et al., Reference Bucher, Dubuc, von Gunten and Morin2016; Kasteridis et al., Reference Kasteridis, Mason, Goddard, Jacobs, Santos and Rodriguez-Sanchez2016), and female sex (Kasteridis et al., Reference Kasteridis, Mason, Goddard, Jacobs, Santos and Rodriguez-Sanchez2016; Ono et al., Reference Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi and Tamai2011). Older females are more likely to live alone than older males (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2019), which may contribute to a greater risk of LTC admission. Several medical factors associated with LTC admission from hospital included severe dementia, severe medical issues, poor functional status, co-morbidity, falls, and hip fractures (Kasteridis et al., Reference Kasteridis, Mason, Goddard, Jacobs, Santos and Rodriguez-Sanchez2016; Takacs et al., Reference Takacs, Ungvari and Gazdag2015; Zekry et al., Reference Zekry, Herrmann, Grandjean, Vitale, De Pinho and Michel2009). Older adults with dementia often have co-morbidities that can impair cognition and increase the challenge of management in the community (Austrom et al., Reference Austrom, Boustani and LaMantia2018). Previous research shows that hospital administrators may follow policies that prioritize discharge to LTC rather than to home in the community, partly because of hospital capacity issues (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2017). Initiatives to train and support care partners in combination with respite care may be effective in delaying LTC admission (Gresham, Heffernan, & Brodaty, Reference Gresham, Heffernan and Brodaty2018).

Interventions examined in included studies that were effective in reducing transitions focused exclusively on hospital readmissions, and were delivered either in-hospital or in-home (Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Chippendale, Resnick and Galvin2015; Cassel et al., Reference Cassel, Kerr, McClish, Skoro, Johnson and Wanke2016; Gustafsson et al., Reference Gustafsson, Sjolander, Pfister, Jonsson, Schneede and Lovheim2017; Noel et al., Reference Noel, Kaluzynski and Templeton2017). Care partners were targeted in three of the four interventions, underscoring the importance of tailoring support and involving care partners in management. For example, reduced readmissions in patients with dementia were achieved after an in-hospital program trained care partners to take part in patient recovery in-hospital and after discharge (Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Chippendale, Resnick and Galvin2015). Previous research advises health care providers to follow principles of family-centred care in ongoing management, such as involving care partners in conversations about medications, providing education about behaviors related to dementia, and soliciting care partners’ reports about indications of pain (Austrom et al., Reference Austrom, Boustani and LaMantia2018).

Findings point to opportunities for reducing the risks of transition to hospital and LTC by strengthening systems of community-based care for people living with dementia and care partners. The need for stronger community care systems is underscored by the significant effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospitals and LTC homes in Canada (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Kumar, Rajji, Pollock and Mulsant2020; Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2020). Further resources are necessary to train and support all segments of the community care system in dementia care, from paid care providers including personal care workers, first responders, and a wide range of health care professionals (e.g., family physicians and occupational therapists) to unpaid care partners who provide the majority of in-home care (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019a). Optimal systems of community care also involve strategies for providing support with daily activities such as shopping, exercise, and technology; coordinating medical services and information sharing across paid providers; and making publicly funded home care and supportive housing widely available across jurisdictions (Boscart, McNeill, & Grinspun, Reference Boscart, McNeill and Grinspun2019; Canadian Academy of Health Sciences, 2019; Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018a). As the needs of people with dementia and their care partners vary and change as the condition progresses, practice guidelines and staffing to ensure early intervention and crisis prevention should also be widely available (Canadian Home Care Association, 2018; Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018a).

Important opportunities for future research were revealed through this review. Complex care trajectories experienced by people living with dementia were not considered by studies in the review. In previous studies of older adults, researchers found between 131 and 240 unique transition patterns across several care settings with varying time frames (Abraham & Venec, Reference Abraham and Venec2016; Sato, Shaffer, Arbaje, & Zuckerman, Reference Sato, Shaffer, Arbaje and Zuckerman2010). Complex trajectories may signal fragmented care (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Aldridge, Gross, Canavan, Cherlin and Bradley2017), particularly when occurring over a short time period. There is also a need for further study of care trajectories from the point of pre-diagnosis to end of life among people living with dementia (Boltz, Reference Boltz, Boltz and Galvin2016; Fortinsky & Downs, Reference Fortinsky and Downs2014). The longest transition time frame in the current review was 5 years (Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Arling, Wanzhu, Rosenman, Counsell and Stump2012), signalling an opportunity for more longitudinal studies that may uncover patterns or group differences that point to discontinuity of care, such as a higher risk of transitions associated with demographic factors (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Aldridge, Gross, Canavan, Cherlin and Bradley2017). Moreover, the risk of complex trajectories has been found to increase with the number of prior transitions experienced by people with dementia (Hathaway, Reference Hathaway2019), further underscoring the importance of longitudinal research. Only one included study examined transition outcomes among female and male sub-populations separately (Ono et al., Reference Ono, Tamai, Takeuchi and Tamai2011). Sex and gender differences in care trajectories should be considered further, as sex and gender differences in neurodegenerative disorders have been observed across many studies (Tierney, Curtis, Chertkow, & Rylett, Reference Tierney, Curtis, Chertkow and Rylett2017). Moreover, no study in the review separately analysed transition patterns in rural and urban sub-populations. A larger share of older adults in Canada live in rural communities than in cities (Statistics Canada, 2017) yet face significant barriers in terms of accessing dementia-specific services (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Kosteniuk, Stewart, O’Connell, Kirk and Crossley2015). Further investigation into rural and urban trajectories would make a substantial contribution to this research area. Finally, further research is needed concerning care trajectories among important sub-populations living with dementia. Traditionally under-represented in these studies are people with intellectual disability and young-onset dementia, and diverse ethnic groups (Boltz, Reference Boltz, Boltz and Galvin2016).

Limitations

The scoping review method allowed for a comprehensive search of the published literature and a subsequent classification of care trajectories experienced by people with dementia. The increase in published literature in recent years on the topic of multiple transitions among people with dementia fits well with the utility of scoping reviews for clarifying key concepts and knowledge gaps in emerging topics (Munn et al., Reference Munn, Peters, Stern, Tufanaru, McArthur and Aromataris2018). It should be noted that this review did not include an assessment of the quality of included studies. Although quality assessment is not a common practice in scoping reviews (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Godfrey, Khalil, McInerney, Parker and Soares2015), the lack of critical appraisal may nonetheless reduce uptake of findings into practice (Levac et al., Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien2010).

Grey literature and non-English articles were excluded, as were mixed-methods and qualitative studies, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. These studies were excluded because the purpose of this review was well suited to quantitative analysis, and less focused on evidence concerning the needs or experiences of people with dementia during the transition process. The latter is an important area that has been investigated with qualitative and mixed methods in previous reviews (Afram et al., Reference Afram, Verbeek, Bleijlevens and Hamers2015; Stockwell-Smith et al., Reference Stockwell-Smith, Moyle, Marshall, Argo, Brown and Howe2018).

Studies included in the current review varied considerably, with some samples including those with Alzheimer’s disease only, others including separate causes of dementia within the same study, and yet others not specifying the causes of dementia. Transition time frames varied from 28 days to 5 years, and studies from several different countries were included to cover the breadth of available evidence, consistent with scoping review methodology (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Godfrey, Khalil, McInerney, Parker and Soares2015). These variations add to the challenge of drawing conclusions based on the findings.

Finally, it was not always possible to determine the location of settings from the information provided in the studies. Routes that began in hospital and involved a transition to a different care site directly afterward were considered to originate in an ‘unspecified’ location for the purpose of the review. We rationalized that individuals were admitted temporarily to hospital from permanent or long-stay living accommodations and that therefore this constituted the first transition. Unspecified locations may in fact be home, LTC, or even another hospital, thus potentially biasing the findings. It is also possible that individuals experienced more than one transition before the initial move to hospital. The time frames imposed on the observation of routes may reduce this possibility; nevertheless, it is a limitation of this study that the framework of multiple transition routes does not capture all possible patterns.

Conclusions

This review found that studies of care trajectories experienced by people with dementia most often involved hospital readmission and discharge from hospital to LTC. Studies reported that risk of hospital readmission and transition from hospital to LTC increased with dementia. Several variables contributing to transition risk were identified, mainly at the level of demographic and medical characteristics such as co-morbidity, as well as severity of both medical issues and dementia. Research opportunities exist to investigate more complex care trajectories, longitudinal trajectories of care, and trajectories experienced by sub-populations of people with dementia. Findings suggest that greater attention should be paid to care trajectories in this population, given the negative outcomes associated with transitions for people with dementia and their care partners. Efforts to strengthen community-based systems of care as part of a multifaceted strategy to reduce transitions are recommended. These efforts should involve considerable investment in comprehensive dementia-specific training to care providers and care partners, widely available home care and supportive housing, and practical support for people with dementia to live independently for as long as safely possible in their communities.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980821000167.