Introduction

The 2014 Alberta Point-in-Time Count identified that of the 6,663 individuals experiencing homelessness across Alberta, 3,555 individuals were Calgary residents (Turner, 2015). A report published by the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy identified that approximately 900 of Calgary’s shelter users are experiencing chronic or long-term homelessness (Kneebone, Bell, Jackson, & Jadidzadeh, Reference Joyce and Limbos2015).

Contemporary research regarding chronic homelessness has focused on the incidence and prevalence of mental and physical health issues, substance use, and vulnerabilities related to living in shelter or rough sleeping. Much of this research indicates that people experiencing homelessness have high rates of childhood trauma, and are at an increased risk of mental health and substance use disorders, negative health outcomes, experiences of victimization, violence, and involvement with the criminal justice system. In a recent Canadian study, mental health and addictions were the most commonly identified health concerns among the homeless population (Campbell, O’Neill, Gibson, & Thurston, Reference Campbell, O’Neill, Gibson and Thurston2015). Researchers have further argued that the longer a person is homeless, the more complex that person’s health issues become. The experience of homelessness is associated with health inequities such as a higher risk of illness and injury, overuse of emergency public systems, and higher mortality rates than same age individuals in the general population (Stafford & Wood, Reference Shortt, Hwang, Stuart, Bedore, Zurba and Darling2017). Inadequate access to housing and health care is a significant contributor to negative health outcomes, and people who are chronically homeless typically have a poorer quality of life and shorter life expectancies than those with shorter experiences of homelessness (Frankish, Hwang, & Quantz, Reference Fazel, Geddes and Kushel2005).

Experiences of childhood trauma have been associated with poor health and social outcomes in adulthood. Multiple studies have used the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) survey to show the relationship between childhood trauma and a wide array of health and social problems including obesity, heart disease, lung disease, cancer, alcohol and illicit drug use, depression, anxiety, memory problems, risk of exposure to domestic violence, homelessness, and premature mortality (Larkin, Shields, & Anda, Reference Krammer, Kleim, Simmen-Janevska and Maercker2012).

Chronic health conditions associated with aging emerge decades earlier amongst people experiencing homelessness (Gelberg, Linn, & Mayer-Oakes, Reference Garibaldi, Conde-Martel and O’Toole1990). Existing research suggests that individuals experiencing homelessness who are over the age of 50 are considered to be older adults, as their health care needs reflect those of individuals 10–20 years older in the general population (CSH & Hearth, Inc., 2011; McDonald, Donahue, Janes, & Cleghorn, Reference McDonald, Dergal and Cleghorn2009). It has been argued that long-term homelessness intensifies health conditions that are typically associated with aging (CSH & Hearth, Inc., 2011). For example, McDonald et al. (Reference McDonald, Dergal and Cleghorn2009) identify that long-term exposure to poor nutrition, trauma, and limited access to health care can speed up the aging process. Fazel, Geddes, and Kushel (2014) further suggest that alcohol, tobacco, and substance use exacerbate the health outcomes of aging individuals experiencing homelessness.

Structural issues specific to older adults create particular barriers to exiting homelessness including limited affordable housing, few job opportunities, long-term poverty, and policies that limit access and amounts of pension and disability income benefits (Grenier et al., Reference Gonyea and Bachman2016). Shelter data from Toronto revealed that older homeless adults tend to exit homelessness more slowly than younger adults and are less likely to move into stable housing. Longer shelter stays for older adults are often the result of unmet housing and health needs for this particular population (Serge & Gnaedinger, Reference Serge, Eberle, Goldberg, Sullivan and Dudding2003; Stergiopoulos & Herrmann, 2003). Gaetz (Reference Frankish, Hwang and Quantz2014) emphasizes that emergency shelters are ill equipped to deal with complex health issues.

Calgary was amongst the first cities in Canada to launch a 10 Year Plan to End Homelessness that included supports to house long-term shelter users based on a Housing First model (Calgary Homeless Foundation, 2014), yet little has been said about the unique health and housing needs of older adults experiencing homelessness in that plan or in other plans across Canada (Grenier, et al, Reference Gonyea and Bachman2016). Given the findings from Hwang (2000) that long-term homelessness and homelessness for aging populations are associated with complex health issues and higher than average mortality rates, understanding the predominant health issues and service needs of this vulnerable population is important.

Background

For people experiencing homelessness, barriers to accessing adequate care are numerous and complex. Financial barriers and non-financial barriers are two primary reasons why people experiencing homelessness may not access health and social services in Canada.

Financial barriers

Although Canada’s publicly accessible health system reduces the financial burden of health care, several medical services are too costly for people experiencing homelessness. Prescription drugs can be unattainable as there is no coverage through the Alberta Health Care Insurance Plan, and many prescriptions may not be covered long term through provincial social assistance programs (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, O’Neill, Gibson and Thurston2015). Even arriving at medical appointments can be financially challenging as some are unable to cover the necessary transportation costs for appointments (Gessler, Maes, & Skelton, Reference Gelberg, Linn and Mayer-Oakes2011).

Non-financial barriers

Researchers have identified that people who do not have a fixed address may have difficulty obtaining the necessary identification to receive a health care card or be eligible for income support programs (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, O’Neill, Gibson and Thurston2015). Inadequate capacity can also be a deterrent, as one study identified that for individuals requiring treatment for alcohol use, long wait times reduced their motivation to seek assistance (Gessler et al., Reference Gelberg, Linn and Mayer-Oakes2011). Finally, it is suggested that “homeless individuals may delay seeking… care because other needs, such as securing food and shelter, are more critical to their daily survival” (Shortt et al., Reference Shah, Claire and Reeves2008, p. 111).

Experiences of discrimination have been reported in multiple Canadian studies (Angus et al., Reference Angus, Lombardo, Lowndes, Cechetto, Ahmad and Bierman2013; Bonin, Fournier, & Blais, Reference Bonin, Fournier and Blais2007; Gessler et al., Reference Gelberg, Linn and Mayer-Oakes2011), often by individuals who reported that disclosing substance use and/or experiences with mental illness led to a denial of services and/or that “ageism” prevented access to sustainable employment and housing opportunities (McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Dergal and Cleghorn2009). Additional barriers for older adults include “fear of illness, mistrust of physicians, fear of being shunned by health professionals, a lack of recognition of the severity of their illness…” (McDonald, Dergal, & Cleghorn, Reference Lee, Mangurian, Tieu, Ponath, Guzman and Kushel2004, p. 8). Older adults are considered “doubly vulnerable” because they are homeless and older, often experiencing stigma and discrimination as a result of myths and misconceptions about homelessness as an experience of laziness and because of ageism (Rich, Rich, & Mullins, Reference Pannell1995). Practices that discriminate against the cultural needs of people have also been identified. Failing to recognize and accommodate the needs of people from diverse cultural backgrounds through culturally appropriate models of care, particularly for immigrants, refugees, and Indigenous peoples may discourage help-seeking behaviour (Hay, Varga-Toth, & Hines, Reference Grenier, Barken, Sussman, Rothwell, Bourgeois-Guérin and Lavoie2006). Distrust of medical providers can create further barriers (Bonin et al., Reference Bonin, Fournier and Blais2007).

Older adults and homelessness

Differences in definitions of “older homeless adults” in cities across Canada make it difficult to assess the national numbers and to make comparisons from city to city. For example, several cities in Canada conduct a “point-in-time count” of homelessness, which is a one-day snapshot of the numbers and demographics of people in emergency shelters,and those sleeping rough and in short-term housing programs, jails, and hospitals with “no fixed address”. City-wide data from Calgary in 2018 report that 5 per cent of people experiencing homelessness were over the age of 65 (Calgary Homeless Foundation, 2018). The City of Toronto (2013) reported that 29 per cent of people experiencing homelessness were over the age of 51. Vancouver categorized older adults as over the age of 54 and reported that 21 per cent of the city’s homeless were in this age group (British Columbia Non-Profit Housing Association, 2017).

Although older adults are not the majority of people experiencing homelessness, their numbers are growing (Calgary Homeless Foundation, 2018) and they are considered to be amongst the most vulnerable (Stergiopoulos & Herrmann, 2003). Brown, Kiely, Bharel, & Mitchell (Reference Brown, Kiely, Bharel and Mitchell2012) argue that older homeless adults often experience the onset of chronic disease at a younger age and report high rates of geriatric diagnoses. Researchers have also shown that individuals experiencing homelessness over the age of 50 have serious mental health concerns (Garibaldi, Conde-Martel, & O’Toole, Reference Gaetz2005; Joyce & Limbos, Reference Hwang2009) and more frequent hospital admissions and ambulatory care than their younger counterparts (Brown & Steinman, Reference Brown and Steinman2013). This group faces additional unique health issues including high rates of physical disability, mobility and sensory limitations, and sometimes dementia (Reference Hay, Varga-Toth and HinesHomelessHub, n.d.; Woolrych, Gibson, Sixsmith, & Sixsmith, Reference Turner2015). Older homeless adults have a life expectancy that is 15–25 years lower than the general population (Woolrych et al., Reference Turner2015). Metraux and colleagues estimate an average life expectancy of 64 years (Metraux, Eng, Bainbridge, & Culhane, Reference McDonald, Donahue, Janes and Cleghorn2011). According to Krammer, Kleim, Simmon-Janevska and Maerker (Reference Kneebone, Bell, Jackson and Jadidzadeh2016), the symptoms associated with childhood trauma in older adults may include “withdrawal, seeking less social support, and not disclosing the event. This may foster the development and maintenance of classic PTSD symptoms” (p. 595).

Despite the many complicating factors affecting older adults experiencing homelessness, they are a relatively neglected sub-group who have received little attention from researchers, policy makers and mainstream service providers (Crane & Joly, Reference Crane and Joly2014). Some researchers have suggested that because of the complex nature of homelessness for older adults, more intensive, specialized and person-centred supports are needed to reduce barriers and improve health and well-being (Gonyea & Bachman, Reference Gessler, Maes and Skelton2009; Pannell, Reference Metraux, Eng, Bainbridge and Culhane2005). Given the many complexities and vulnerabilities of this group, the experiences and characteristics of the older homeless population must be critically examined in conjunction with existing practices to ensure that the health and service needs of this vulnerable population are addressed.

A review of the literature by Grenier et al. (Reference Gonyea and Bachman2016) identified that there are significant knowledge gaps on the complexities associated with adequately supporting older adults experiencing homelessness into sustainable and supportive housing. Our study is an attempt to help fill this gap by examining the experiences of childhood trauma and the service and support needs of this highly vulnerable and under-studied group.

Methods

In a recent study in Calgary, Alberta, we surveyed 300 people in shelters and sleeping rough in Calgary, Alberta. Of them, 47 per cent were over the age of 50. By comparing the responses of people over the age of 50 with those of younger people, our intention was to evaluate health issues and experiences with childhood trauma to identify the ways in which we can more adequately meet the needs of the aging homeless population and potentially inform interventions and strategies associated with municipal plans to end homelessness.

Before this study, the health issues and service needs of older adults experiencing chronic homelessness in Calgary, Alberta were unknown, particularly with regard to experiences of childhood trauma. To address these knowledge gaps, we examined the following research questions.

(1) How complex are the physical and mental health issues for Calgarians over the age of 50 who are experiencing chronic homelessness?

(2) What are the unmet health needs of this group?

(3) Are there “predictors” of chronic homelessness (such as childhood trauma) that could be addressed with changes to health policy or service delivery?

Participants were recruited from two emergency shelters in Calgary, as well as from a small group of rough sleepers. All participants provided signed consent prior to the survey and received $25 as compensation for their time. The University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board approved this study. The surveys consisted of 88 questions including socio-demographics, the ACE, and questions specific to physical and mental health issues and experiences accessing supports.

Data Analysis

Excel and SPSS were used for analysis beginning with descriptive statistics for the samples of respondents who were 50 and older (n = 142) and respondents who were under the age of 50 (n = 158). This consisted of examining response distributions and the respective percentages across each survey question. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were then calculated where appropriate, thus providing insight into the statistical significance and strength of relationships between variables.

Results

Demographics

The majority of respondents were male (82%), nearly half were single (49%), and most reported living in Calgary for more than 10 years (68%). When examining respondents’ living situation as children and adolescents, 29 per cent reported they had been in foster care or removed from their family. When examining ethnicity and cultural background, 76 per cent of older adults identified as Caucasian and 17 per cent identified as First Nations, Inuit, or Métis. Of the older adults who identified as Indigenous, 71 per cent had family members who attended Residential School and 33 per cent had attended Residential School themselves.

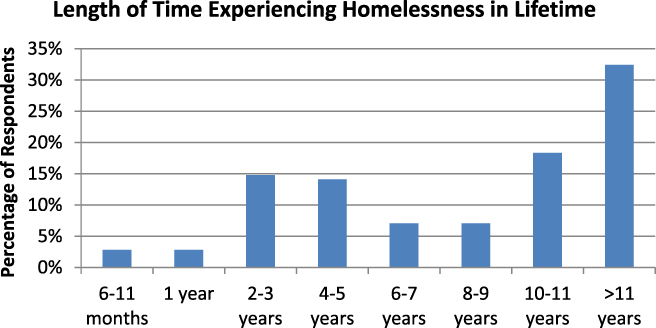

Length of time experiencing homelessness was another important variable, as the largest proportion of respondents had experienced homelessness for 10 years or longer (51%) (see Figure 1). This suggests that the majority of respondents had long-term exposure to the adverse consequences of homelessness.

Figure 1: Respondents who are ≥ 50 years of age: n = 142

Health

Respondents were asked to identify which of the physical health conditions shown in Table 1 they had been diagnosed with. This provides insight into the ways in which older and younger respondents’ physical health status differs.

Table 1: Respondents’ reported physical health conditions

Note. STD = sexually transmitted disease, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Mental Health

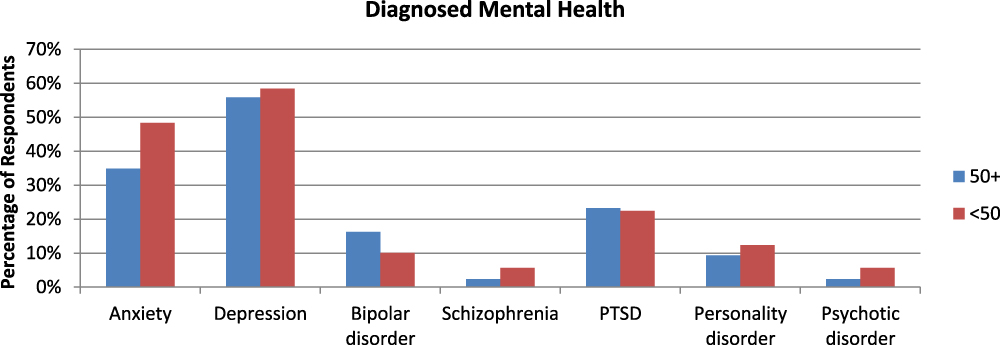

A smaller proportion of respondents over the age of 50 reported that they had received mental health diagnoses (30%, as opposed to 56% of respondents under the age of 50) (see Figure 2). Of respondents over 50 with previous diagnoses, fewer reported that they had undiagnosed mental health issues (42%, as opposed to 48% for those under 50).

Figure 2: Respondents who are ≥ 50 years of age and have been diagnosed with mental illnesses: n = 43; respondents who are < 50 years of age and have been diagnosed with mental illnesses: n = 89

Older respondents reported bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) slightly more frequently; however, a greater proportion of younger respondents had been diagnosed with anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, personality disorders, and psychotic disorders.

When examining the correlation between respondents’ age and respective health conditions, all three relationships were statistically significant. The number of physical health diagnoses increased with age, yet the number of diagnosed and undiagnosed mental health issues decreased as age increased (see Table 2).

Table 2: Age and health conditions correlations

Note. ** Correlation is significant at the .01 level (2 tailed).

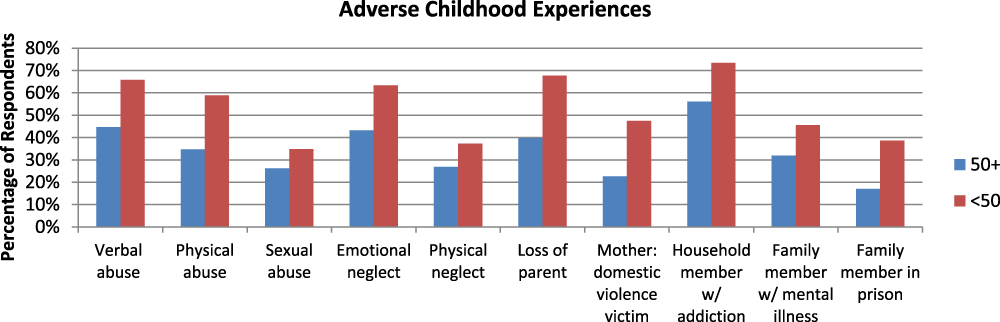

Adverse Childhood Experiences

The widely used ACE survey shows a direct relationship between experiences of childhood trauma and health, substance abuse, and social issues in adulthood (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). The ACE survey assigns a “score” based on the number of “types” of childhood trauma a person experienced before the age of 18. The survey includes questions about verbal, physical, and sexual abuse, along with physical and emotional neglect, loss of a parent, witnessing domestic violence, household members’ addiction, mental illness, and parental incarceration, thus producing a score out of ten.

When examining the percentage differences between older and younger respondents, it is evident that the younger sub-group disproportionately reported experiencing each of the adverse childhood experiences listed in Figure 3. When examining the average ACE scores from each sub-group, respondents over the age of 50 reported an average of 3.43 experiences, as opposed to an average of 5.33 for respondents under 50 (see Table 3). There is a negative relationship between age and adverse childhood experiences, which suggests that as age increases, the number of reported adverse childhood experiences decreases.

Figure 3: Respondents who are ≥ 50 years of age: n = 141; respondents who are < 50 years of age: n = 158.

Table 3: Adverse childhood experiences and age correlation

Note. **Correlation is significant at the .01 level (2 tailed).

Access to Services

Older adults expressed significant barriers to accessing services and supports. The most commonly reported barriers were financial, wait lists, and asking for help but not receiving it. Despite access to free health care, 36 per cent of older adults reported not having enough money for medications (compared with 30% of younger adults) and 37 per cent reported not having access to transportation (compared with 22% of younger adults). Access to residential treatment was particularly difficult, with 37 per cent reporting that they had asked for help but were refused (compared with 22% of younger adults); 50 per cent said that they had been rejected because of long wait lists (compared with 33% of younger adults).

Discussion

Looking at the length of homelessness experienced, more than half of our participants had been homeless continuously for more than 10 years. Calgary’s homeless over the age of 50 were predominantly single, white males, the majority of whom had lived in Calgary for several years. However, 17 per cent of our sample of older adults identified as Indigenous. This is a disproportionate over-representation, as only 3 per cent of Calgary’s general population identify as Indigenous (Statistics Canada, Reference Stafford and Wood2016). Numerous studies have shown significant health disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians and rates of infectious and chronic diseases are substantially higher amongst Indigenous Canadians. In a study in Toronto (Shah, Claire, & Reeves, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2013), the average age of death for Indigenous people accessing four different health clinics was 37 years of age. Comparatively, the average age of death amongst the general Toronto population was 75. The most common causes of death amongst Indigenous people were associated with homelessness, physical abuse, and substance use compounded by chronic conditions (Shah et al., Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2013). Akee and Feir (Reference Akee and Feir2018) argued that the proportional difference in mortality between people of Indigenous status and non-Indigenous people in Canada is larger than the difference in mortality rates comparing Native Americans and African Americans with non-Hispanic white people in the United States. These authors further argue there has been no substantive improvement in mortality rates for Indigenous people in Canada in the last 40 years.

A deeper examination of support and service needs, including cultural supports, is warranted given the relationship among residential schools, intergenerational trauma, high rates of homelessness, and significant disparities for Indigenous people (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Reference Troy2015)

Foster care involvement also emerged as important, with 29 per cent of respondents having been removed from their homes in childhood. Although this finding supports previous research findings of Serge, Eberle, Goldberg, Sullivan, and Dudding (Reference Rich, Rich and Mullins2002), further work is needed to understand the relationship between system interactions in childhood and future chronic homelessness.

The older sub-group disproportionately reported higher rates of most physical health conditions with the exception of HIV/AIDS, asthma, and brain/head injury. Higher rates of hepatitis A, B, and C; cancer; high blood pressure; stroke; heart attack; arthritis; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); emphysema; and bronchitis are consistent with Hwang’s (Reference Hwang2001) findings that long-term exposure to homelessness and/or the risks associated with it (e.g., substance use) increase rates of heart and lung diseases. Further issues including dental problems, mobility issues, frostbite, skin and foot problems, and chronic pain, may be associated with long-term exposure to weather, “wear and tear” and/or limited access to appropriate health care. Particularly troubling was that our sample of older adults reported significant barriers to accessing services including the prohibitive costs of medication, long wait lists, and asking for help but not receiving it. Further research is needed to understand the role of age and ageism in being denied access.

A study by Lee et al. (Reference Larkin, Shields and Anda2017) surveyed older adults experiencing homelessness and results showed that this group had higher rates of childhood trauma than the non-homeless population, and subsequently, had higher rates of mental health issues. Our results show that older adults reported fewer experiences of childhood trauma than younger adults, yet reported comparable rates of PTSD. This is in contrast to what we might expect, which is that more profound experiences of childhood trauma lead to more complex mental health issues which lead to longer time in homelessness. In trying to understand why older adults report fewer traumatic events in childhood, we could surmise that younger people have previous experiences shaping their health and social outcomes that differ significantly from the older homeless population. Alternatively, we can speculate that perhaps the length of time between childhood and older adulthood negatively affects memory, or perhaps that long-term exposure to homelessness and the risks associated with it affects memory and/or older adults may be less likely to speak about childhood trauma than younger adults. It may be more likely, however, as Krammer et al. (Reference Kneebone, Bell, Jackson and Jadidzadeh2016) argued, that childhood trauma in older adults manifests as classic PTSD and its symptoms rather than as other mental health issues. It is important to note that whereas older adults reported, on average, two fewer childhood traumatic experiences than younger adults, the average ACE score for the general population is 1.4 (Troy, Reference Stergiopoulos and Herrmann2014), the average for our sample of older adults was 3.4, or two and half times higher. We can therefore argue that childhood trauma should be understood and addressed when developing service responses. Our results show higher than average rates of childhood trauma, very poor physical health, and disproportionately high numbers of Indigenous older adults amongst Calgary’s homeless population. These highlight the necessity of responses that are age and culturally appropriate as well as trauma informed.

An important limitation to this study is related to the use of the ACE survey. The survey itself assesses the number of “types” of trauma experienced in childhood, but it does not assess the duration, intensity, and chronicity of trauma. In other words, we do not know how many times someone may have experienced a traumatic event, nor can we determine whether or not witnessing violence would have the same impact as being a victim of sexual abuse. A more fulsome examination of the depth and breadth of childhood trauma would be an important next step in identifying specific interventions to address its impact.

Our study supports previous research in several ways, as we were able to show higher rates of health issues including those associated with aging in the older adult group. However, our findings do not support arguments that mental health issues increase with long-term exposure to homelessness. Results showed higher than average rates of childhood trauma and a disproportionate number of older Indigenous adults amongst Calgary’s chronically homeless. Our portrait of late life homelessness in Calgary, Alberta shows that to effectively and efficiently address the needs of the older adult homeless population, policy makers and service providers need to recognize the significant disparities facing older adults and consider a wide range of factors in developing programs including preventative measures to help stop homelessness before it begins. Older adults face barriers to sustainable housing and supports that are complicated by complex health issues, high rates of PTSD, limited options for employment, and likely ageism. Adults experiencing homelessness are not a homogeneous group. Their health and service needs differ and programmatic interventions to address homelessness need to be flexible and adaptable to meet the varied personal, health, cultural, and social needs of this diverse group. Recognition of the intersecting and cumulative effects of childhood trauma, long-term homelessness, cultural differences, and age could inform changes to policy to reduce siloes around public systems, and given that older adults are at higher risk for an early death, they should be prioritized for housing programs through plans to end homelessness.

To understand and respond to the impact of trauma matters for service delivery, significant investment in age-appropriate supports should be trauma informed. This may include the targeted provision of permanent supportive housing coupled with consistent access to health and social services, designed specifically to meet the needs of older adults, including free or subsidized medications and access to counselling and cultural supports. Future research could assess the impacts of supported housing on health and social outcomes for this vulnerable population and begin to assess gender and cultural differences in more detail.