Background

In December 2015, Quebec became the first province in Canada to legalize medical aid in dying, defined as “care consisting in the administration by a physician of medications or substances to an end-of-life patient, at the patient’s request, in order to relieve their suffering by hastening death” (CanLII, 2014). The government of Canada partially decriminalized assistance in dying 6 months later, also allowing nurse practitioners to perform the act and patients to self-administer the substance in order to bring about their own death (Government of Canada, 2016). Current eligibility criteria for medical aid/assistance in dying (MAID) are similar but not identical in the two jurisdictions. The federal legislation requires the person’s death to be “reasonably foreseeable,” whereas that in Quebec limits access to patients who are at the end of their lives. In all Canadian provinces and territories, however, the person must be competent to provide express consent immediately prior to the provision of MAID (Council of Canadian Academies, 2018). A neurocognitive disorder does not necessarily disqualify a person for MAID (Canadian Association of MAID Assessors and Providers, 2019; Downie, Reference Downie2019). Patients with dementia as the sole underlying medical condition, but who still have decision-making capacity, have been found eligible and have received assistance in dying, at least in British Columbia (CBC Radio, 2019; Frangou, Reference Frangou2020; Grant, Reference Grant2019). To our knowledge, no such cases have been reported in Quebec, perhaps because of the more stringent “end-of-life” criterion of the Quebec legislation. However, in Canada, competent persons who fear losing their decision-making capacity cannot provide valid consent to MAID by means of an advance request (Council of Canadian Academies, 2018).

At both levels of government, legislation was preceded by discussions as to whether MAID should be accessible to non-competent patients as well, on the basis of a request written before losing decisional capacity (Collège des Médecins du Québec, 2009; Provincial-Territorial Expert Advisory Group on Physician-Assisted Dying, 2015; Select Committee on Dying With Dignity, 2012; Special Joint Committee on Physician-Assisted Dying, 2016). Sensing a lack of social consensus on this controversial issue, neither government gave non-competent patients access to MAID through an advance request. Instead, they each tasked a group of experts to reflect on the issue. The Council of Canadian Academies Expert Panel on Advance Requests for MAID published an extensive review of the state of knowledge on this issue (Council of Canadian Academies, 2018) but did not provide recommendations to governments, as doing so was excluded from its mandate (Halifax Group, 2020). Publicly released in November 2019, the report of the expert panel appointed by the Quebec minister of health and social services recommended that, under conditions specified in the report, MAID be made available through requests made before the person has lost decision-making capacity (Groupe d’experts sur la question de l’inaptitude et l’aide médicale à mourir, 2019). On January 27, 2020, the Quebec government held a forum on advance requests for MAID to further consult stakeholders on this issue (Forum national sur l’évolution de la Loi concernant les soins de fin de vie, 2020). To our knowledge, no further development has since occurred in Quebec, perhaps because of current governmental efforts to control the COVID-19 pandemic.

MAID is a rapidly changing area of practice. In September 2019, the Quebec Superior Court found the eligibility criterion requiring that a person’s natural death be reasonably foreseeable, as well as the end-of-life criterion from Quebec’s Act respecting end-of-life care, to be unconstitutional (Truchon v. Attorney General of Canada, 2019). The federal and Quebec governments chose not to appeal the court’s ruling. Despite the fact that the ruling applies only to Quebec (Halifax Group, 2020), the federal government committed itself to responding to the court’s decision by amending the legal framework for MAID set out in the Criminal Code. On February 24, 2020, following extensive consultations across Canada through regional roundtable meetings and an online questionnaire, the minister of justice and attorney general of Canada introduced Bill C-7 (Government of Canada, 2020a). The bill would remove the requirement for a person’s natural death to be reasonably foreseeable in order for that person to be eligible for MAID, while retaining all other existing eligibility criteria. It would also introduce a two-track approach to procedural safeguards based on whether or not a person’s natural death would be reasonably foreseeable. Existing safeguards would be maintained for eligible persons whose death would be reasonably foreseeable, but some would be eased (e.g., a 10-day waiting period between the formal request and the provision of MAID would no longer be required). New and modified safeguards would apply to eligible persons whose death was not reasonably foreseeable (e.g., the requirement that one of the assessors have expertise in the condition that is causing the person’s suffering and a delay of at least 90 days between the day of the first eligibility assessment and the day on which MAID was provided). With a prior written arrangement, the bill would allow dying persons who have been found to be eligible to receive MAID and are awaiting its provision on a specified day, to obtain MAID even if they lose the capacity to provide final consent, unless they demonstrate signs of refusal to have the substance administered or resistance to its administration. Involuntary words, sounds, or gestures made in response, for example, to the insertion of a needle, would not constitute refusal or resistance.

In summary, proposed changes to Canada’s MAID legislation would not expand eligibility to non-competent persons through an advance request. Shortening the 90-day waiting period for patients with dementia whose death is not reasonably foreseeable is unlikely to change the current situation, given the difficulty of determining with certainty when a patient might become decisionally incompetent. These issues will likely be considered further during the mandatory parliamentary review of the law, initially scheduled to begin in June 2020 (Government of Canada, 2020b).

In September 2016, a few months after the Quebec and federal legislation had come into effect, we launched an anonymous vignette-based postal survey among Quebec physicians (vignette shown in the Appendix) to inform the social debate on the highly sensitive and complex health care issue of giving non-competent patients access to MAID through an advance request. The survey explored the physicians’ attitudes towards extending MAID to non-competent patients with dementia and their willingness to administer MAID themselves should it be legal. Answers were given for a fictitious female patient, at two stages along the dementia trajectory: the advanced stage, in which the now-incompetent patient was described as likely having several more years to live, and the terminal stage, in which she had only a few weeks left to live (Bravo et al., Reference Bravo, Rodrigue, Thériault, Arcand, Downie and Dubois2017). As reported previously (Bravo et al., Reference Bravo, Rodrigue, Arcand, Downie, Dubois and Kaasalainen2018), 45 per cent of the 136 respondents (response rate = 25.5%) supported giving the patient access to MAID at the advanced stage, and 71 per cent supported giving the patient access to MAID at the terminal stage. Should the practice be accessible to such patients, 31 per cent of physicians indicated being likely to administer MAID themselves at the advanced stage, and 54 per cent indicated being likely to administer MAID at the terminal stage, on the basis of a prior written request.

Few studies have investigated people’s characteristics associated with attitudes towards assisted dying in dementia (Tomlinson & Stott, Reference Tomlinson and Stott2015), and even fewer have done so among samples of physicians (Rurup, Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Pasman, Ribbe, & van der Wal, Reference Rurup, Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Pasman, Ribbe and van der Wal2006; Ryynänen, Myllykangas, Viren, & Heino, Reference Ryynänen, Myllykangas, Viren and Heino2002; van Tol, Rietjens, & van der Heide, Reference van Tol, Rietjens and van der Heide2010; Watts, Howell, & Priefer, Reference Watts, Howell and Priefer1992). Of the demographic characteristics investigated, religiosity is the only one consistently related to physicians’ attitudes, with less support found among those having stronger religious beliefs. Regarding physicians’ practice characteristics, van Tol et al. (Reference van Tol, Rietjens and van der Heide2010) found Dutch physicians who had performed euthanasia in the past 5 years to be more willing to fulfill a euthanasia request. Of the three other practice characteristics investigated by these authors – type of practice, work experience, and training in palliative care – none were associated with willingness to grant a euthanasia request (van Tol et al., Reference van Tol, Rietjens and van der Heide2010). To further inform current deliberations in Canada on whether MAID should be extended to non-competent patients, we herein compare demographic and practice characteristics of our respondents according to whether they reported being (1) open or not to extending MAID to non-competent patients with dementia, and (2) willing or not to administer MAID themselves should it be legal.

Methods

Survey

As described in more detail elsewhere (Bravo et al., Reference Bravo, Rodrigue, Thériault, Arcand, Downie and Dubois2017; Reference Bravo, Rodrigue, Arcand, Downie, Dubois and Kaasalainen2018), we conducted the survey on a random sample of physicians provided by the Quebec College of Physicians. Eligibility was restricted to physicians who were caring for patients with dementia at the time of the survey. We mailed sampled physicians a first survey package on September 5, 2016, with reminders sent 2 and 9 weeks later. We closed the survey on March 1, 2017. The survey was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the CIUSSS de l’Estrie – CHUS (file #2016-623). Consent was inferred from physicians’ returning the questionnaire.

Measures

The vignette (see Appendix) used to measure attitudes featured a female patient moving along the dementia trajectory, from the early stage at which she was competent to make decisions, to later stages (labelled advanced and terminal) at which she had lost capacity. Following discussions with her physician and with close relatives about her health care wishes, the patient had written a request for MAID to be carried out when she could no longer recognize her loved ones. Separately for the advanced and terminal stages, respondents indicated (1) the extent to which they find it acceptable that the current legislation be changed to allow a physician to administer drugs that would cause the patient’s death, and (2) the likelihood that they would administer MAID themselves should the patient be one of their own and the practice be legal. Answers were provided on five-point Likert-type scales and dichotomized for statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

We investigated potential correlates of physicians’ attitudes, first with a series of bivariate analyses, then by including correlates found significant at the 0.20 level in multivariable logistic regression models. Variables non-significant at the 0.05 level were then removed gradually. Linearity of the two variables measured on a continuous scale (age and religiosity) was confirmed a priori. All reported p values are two sided. Associations that remained statistically significant following the multivariable analyses are expressed using odds ratios, along with their 95 per cent confidence interval. Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS for Windows, version 24.

Results

Bivariate Analyses

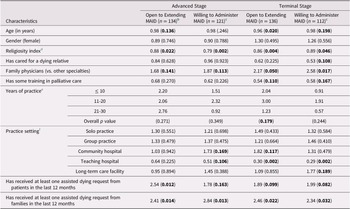

Table 1 compares physicians on demographic and practice characteristics according to whether they were open to extending MAID to non-competent patients with dementia (first outcome), or willing to administer MAID themselves should it be legal (second outcome), separately for the advanced and terminal stages. At the advanced stage, five candidate variables were related to the first outcome when examined individually (age, religiosity, being a family physician, and exposure to assisted dying requests from patients or families) and six to the second outcome (religiosity, being a family physician, practicing in a community or teaching hospital, and exposure to assisted dying requests from patients or families). At the terminal stage, nine variables were associated with the first outcome (age, religiosity, being a family physician, training in palliative care, years of practice, practicing in a community or teaching hospital, and exposure to assisted dying requests from patients or families) and nine with the second outcome (age, religiosity, having cared for a dying relative, being a family physician, training in palliative care, practicing in a teaching hospital or long-term care facility, and exposure to assisted dying requests from patients or families).

Table 1. Results from bivariate analyses linking physician characteristics with being (1) open to extending MAID to non-competent patients with dementia and (2) willing to administer MAID themselves should it be legala

Note.

a Data shown are odds ratios, with p values in parentheses, derived from valid cases. Few data were missing: between 1 for training in palliative care and 8 for age. Characteristics associated with p values < 0.20 (in bold) were included in the multivariable analyses.

b Two physicians provided no answer to the questions pertaining to the advanced stage.

c Restricted to physicians who answered yes when asked whether the patient depicted in the vignette could be one of their own.

d Derived from combining answers to four questions developed by Statistics Canada for the General Social Survey (Clark & Schellenberg, Reference Clark and Schellenberg2006). Total scores range from 0 to 13 and are interpreted in three broad categories: low (0–5), moderate (6–10), and high (11–13).

e Reference group: More than 30.

f More than one answer could be given.

MAID = medical aid/assistance in dying.

Multivariable Analyses

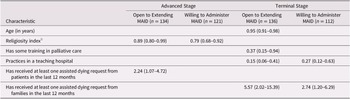

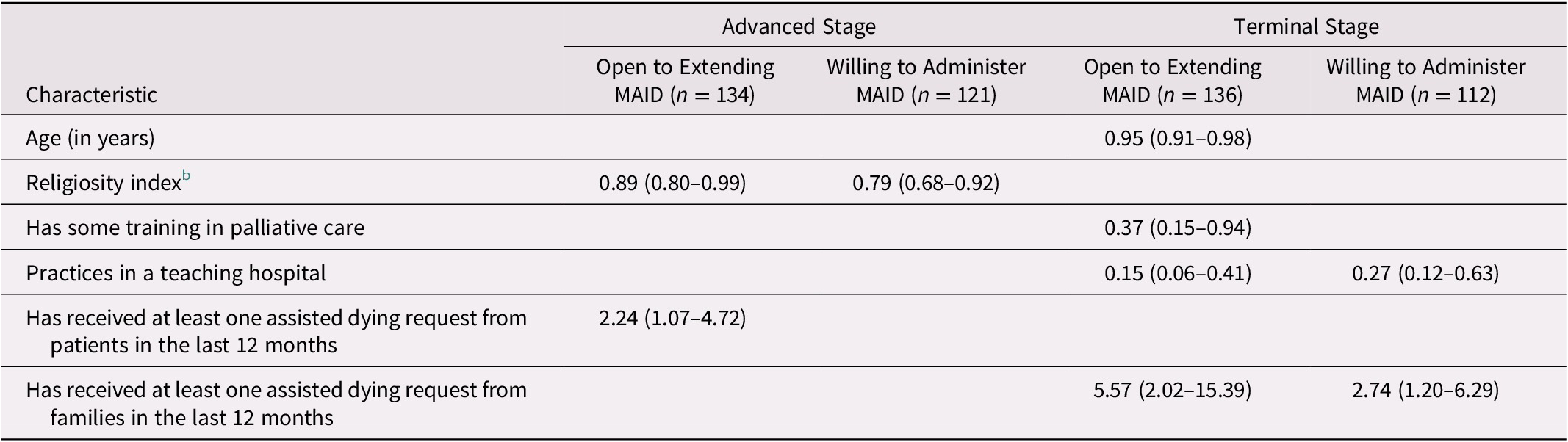

Table 2 reports the results of combining these characteristics in multivariable logistic regression models. At the advanced stage, two characteristics predicted the first outcome (religiosity and exposure to assisted dying requests from patients), and one predicted the second outcome (religiosity). At the terminal stage, four characteristics remained significantly associated with the first outcome (age, training in palliative care, practicing in a teaching hospital, and exposure to assisted dying requests from families), and two remained significantly associated with the second outcome (practicing in a teaching hospital and exposure to assisted dying requests from families). The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit test was non-significant for all four multivariable models, with p values ranging from 0.171 to 0.902.

Table 2. Physician characteristics found statistically significant in at least one of the four multivariable logistic regression models, at the 0.05 significance level a

Note.

a Data shown are odds ratios, with 95 per cent confidence intervals in parentheses.

b Derived from combining answers to four questions developed by Statistics Canada for the General Social Survey (Clark & Schellenberg, Reference Clark and Schellenberg2006). Total scores range from 0 to 13 and are interpreted in three broad categories: low (0–5), moderate (6–10), and high (11–13).

MAID = medical aid/assistance in dying.

Compared with physicians who had not received assisted dying requests from patients or families in the 12 months preceding the survey, physicians exposed to such requests had between 2.2 and 5.6 times higher odds of being open to extending MAID to non-competent patients with dementia or of being willing to administer MAID themselves, depending on the outcome and stage. As all other odds ratios were lower than 1, an increase in the value of the predictor decreased the odds that the physician reported being open to extending MAID or being willing to administer MAID him- or herself.

Discussion

The removal of the “reasonably foreseeable natural death” and “end-of-life” eligibility criteria is expected to broaden access to MAID, but proposed amendments would not allow assistance in dying to non-competent patients on the basis of an advance request. The difficult decision to maintain the prohibition or to permit MAID in such circumstances with additional safeguards therefore still lies ahead for the federal Parliament and the Quebec National Assembly. Having observed some support among Quebec physicians for extending MAID to non-competent patients with dementia, and noting among them a significant proportion willing to administer MAID themselves should the patient be one of their own, we sought to describe these physicians to inform policy makers as they further develop the MAID legal framework.

Overview of Main Findings and Comparison with the International Literature

We found that physicians who were older, scored higher on the religiosity index (implying being more religious), had received some training in palliative care, practiced in a teaching hospital, and had not been exposed to assisted dying requests in the 12 months preceding the survey held less favourable attitudes towards MAID in dementia. Lesser support for hastening death practices has been observed among older survey respondents, including nurses, but not among physicians (Tomlinson & Stott, Reference Tomlinson and Stott2015). Perhaps the age effect observed in other populations is gradually spreading to the medical community. Our finding regarding the religiosity effect is consistent with those of others (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Marcoux, Bilsen, Deboosere, van der Wal and Deliens2006; Hendry et al., Reference Hendry, Pasterfield, Lewis, Carter, Hodgson and Wilkinson2013; Tomlinson & Stott, Reference Tomlinson and Stott2015). Contrary to van Tol et al. (Reference van Tol, Rietjens and van der Heide2010), we found physicians trained in palliative care to be less likely to support MAID in dementia. These physicians likely have greater knowledge of other means of relieving patients’ suffering at the end of life (e.g., palliative sedation), which may lower their support for MAID. We also found physicians practicing in a teaching hospital to have less favourable attitudes towards MAID for non-competent patients. Teaching hospitals in Quebec are all located in urban areas where palliative care is more accessible to patients. Greater access to palliative care may explain greater opposition to MAID from physicians working in these settings. To our knowledge, exposure to assisted dying requests has not been investigated as a potential correlate of physicians’ attitudes towards death-hastening practices. Arguably, physicians exposed to such requests may have been caring for patients whose suffering could not be relieved successfully, leading them to conclude that MAID may be appropriate in exceptional circumstances (Georges, The, Onwuteaka-Philipsen, & van der Wall, Reference Georges, The, Onwuteaka-Philipsen and van der Wal2008).

Challenges of Carrying out Advance Requests for MAID

For people living with dementia, advance requests for MAID would respond to their desire to choose the circumstances of their death, their wish to avoid burdening others, and their fear of losing dignity and the ability to perform activities that give meaning to their life, including engagement with their loved ones (Menzel, Reference Menzel2019). As the Canadian population continues to age, and the prevalence of capacity-limiting conditions increases, the demand for advance requests for MAID could increase as well (Council of Canadian Academies, 2018). The increased demand may also come from family caregivers who have experienced the complexity of making end-of-life decisions on behalf of an incapacitated loved one. Yet, responding to advance requests for assistance in dying, should they be allowed, would no doubt be a very difficult task for health care professionals (mainly physicians, in Quebec) because of the heavy responsibility and emotional burden of deciding whether and when to follow through with the request (Brooks, Reference Brooks2019; Schuurmans et al., Reference Schuurmans, Bouwmeester, Crombach, van Rijssel, Wingens and Georgieva2019). For MAID assessors, the task would involve difficult judgments about the patient’s decision-making capacity, whether the request was voluntary and well informed, the nature and intolerability of the patient’s suffering, and persistence of the desire for MAID. More uncertainty in interpreting the advance request and applying it to the patient’s current situation would likely be experienced with requests drafted years before their implementation. Resistance during the procedure would further increase uncertainty for the provider (Council of Canadian Academies, 2018).

A significant proportion of our survey respondents reported being willing to administer MAID themselves, with the proportion higher at the terminal stage and higher still among subgroups of respondents (e.g., those of younger age, or with prior exposure to advance dying requests). Stated opinions on hypothetical scenarios may differ from actual practice (Bouthillier & Opatrny, Reference Bouthillier and Opatrny2019; Council of Canadian Academies, 2018). Nonetheless, our survey and two others (Canadian Association of MAID Assessors and Providers, 2017; Fédération des médecins spécialistes du Québec, 2020) suggest that a significant number of health care professionals would be willing to provide MAID to an eligible patient who lacked capacity but had made an advance request for MAID. These providers would need to be comfortable with the many sources of uncertainty surrounding the irreversible decision to actively end the life of patients who can no longer consent to the act.

International Experiences with Advance Requests for MAID

Internationally, there are little publicly available data on the practice of following advance euthanasia directives (AEDs) for patients with dementia who lack decision-making capacity (Council of Canadian Academies, 2018). Of the four countries that allow them, two (Belgium and Luxembourg) limit their application to patients who are irreversibly unconscious, and one (Colombia) to those whose death is imminent. Nearly all information on how AEDs are working in practice comes from the Netherlands. Overall, compliance with AEDs for people with dementia is quite low. Mangino, Nicolini, De Vries, and Kim (Reference Mangino, Nicolini, De Vries and Kim2020) conducted a content analysis of dementia euthanasia reports published by the Dutch euthanasia review committees between 2011 and 2018. Seventy-five patients were reviewed, of which 16 received euthanasia based on an AED. According to de Boer, Dröes, Jonker, Eefsting, and Hertogh (Reference de Boer, Dröes, Jonker, Eefsting and Hertogh2010), Dutch physicians have been reluctant to hasten the deaths of incompetent patients with dementia because of the impossibility of communicating meaningfully with them, making it difficult for physicians to determine whether the patient is suffering unbearably, ascertain that the advance request was in fact voluntary, and decide on the moment to carry it out. The importance of communication was also underscored by Brooks (Reference Brooks2019), following her scoping review of the international literature on the perspectives and experiences of health care providers involved in the care of persons receiving assistance in dying.

A need for Guidance and Clarity

If advance requests for MAID were permitted in Canada, provincial/territorial professional regulatory bodies would need to develop policy documents, professional standards, and detailed guidelines for eligibility assessment and the provision of MAID to non-competent patients. Guidelines should in particular clarify the role for health care professionals in assessing intolerable suffering and deciding how to deal with a patient’s resistance to the MAID procedure, in a context in which it may not be possible for the health care professional to have a meaningful conversation with the patient. Also needed would be comprehensive process pathways, as well as learning resources and capacity-building opportunities for professional development that focus specifically on responding to advance requests for MAID. Emotional support services for professionals involved in implementing advance requests for MAID should also be made available across the country (Brooks, Reference Brooks2019; Canadian Association of MAID Assessors and Providers, 2017; Council of Canadian Academies, 2018; Silvius, Memon, & Arain, Reference Silvius, Memon and Arain2019).

Advance requests for MAID would require reliance on others (health care professionals, close relatives) to interpret and carry out instructions recorded by patients, sometimes years before losing capacity. Although misinterpretation cannot be avoided entirely, strategies have been identified that would likely reduce its occurrence (Council of Canadian Academies, 2018). These include (1) drafting a well-informed, detailed request that describes as precisely as possible, preferably in the patient’s own words and with the assistance of a health care professional who has known the patient for some time (Brooks, Reference Brooks2019), circumstances constituting intolerable suffering and when MAID should be performed; (2) designating a trusted loved one who is aware of the request, can speak to the patient’s values, beliefs and wishes, and is willing to advocate for the patient; (3) continued conversations among the patient who made the advance request, the designated loved one, and the health care professional about the content of and reasons for the request; (4) documenting these conversations in the patient’s medical record; and (5) updating the request as the disease progresses.

Limitations

We acknowledge limitations to the portrait we have drawn of Quebec physicians who reported being open to advance requests for MAID and willing to administer MAID themselves should they be allowed. These include a low response rate, although ours is similar to that of other surveys on assisted dying conducted among physicians (Bouthillier & Opatrny, Reference Bouthillier and Opatrny2019; Marcoux, Boivin, Mesana, Graham, & Hébert, Reference Marcoux, Boivin, Mesana, Graham and Hébert2016; Rosenberg et al., Reference Rosenberg, Butler, Caprio, Rhodes, Braun and Vitale2020); and the possibility that characteristics influencing attitudes differ between respondents and non-respondents. Our sample was homogeneous with regard to ethnicity (95% of the respondents identified themselves as Caucasian), which precluded investigating attitudes of physicians from minority backgrounds. The survey was conducted in Quebec shortly after MAID had become accessible to competent patients. Correlates of physicians’ attitudes may be different in other Canadian provinces and territories, as well as in jurisdictions where practices that hasten death are illegal or restricted to physician-assisted suicide. Two recent qualitative studies conducted among Quebec physicians (Bouthillier & Opatrny, Reference Bouthillier and Opatrny2019; Dumont & Maclure, Reference Dumont and Maclure2019) found diverse motives for refusing to provide MAID to currently eligible patients, including the anticipation of a heavy emotional burden, unfamiliarity with the MAID process, and fear of stigmatisation. These variables were not measured in our survey. In future studies, these variables could be measured in conjunction with ours to determine their respective effect on willingness to provide MAID to non-competent patients should they have access to it.

Conclusion

We found age, religiosity, training in palliative care, practicing in a teaching hospital, and exposure to assisted dying requests from patients or families to be associated with physicians’ attitudes towards MAID for non-competent patients with dementia. Knowledge of these influential characteristics will inform ongoing deliberations regarding the extension of MAID to these vulnerable patients. Should the eligibility criteria be broadened to include this population, as recently recommended by the Groupe d’experts sur la question de l’inaptitude et l’aide médicale à mourir (2019), efforts will be needed to ensure that patients who requested MAID prior to losing capacity, and meet the yet-to-be-defined legal requirements, can indeed receive assistance in dying. Equally important will be finding ways of supporting health care professionals confronted with such requests and ensuring that none are pressured “to cross their own personal boundaries” (de Boer et al., Reference de Boer, Depla, den Breejen, Slottje, Onwuteaka-Philipsen and Hertogh2019; Georges et al., Reference Georges, The, Onwuteaka-Philipsen and van der Wal2008; Snijdewind, van Tol, Onwuteaka-Philipsen, & Willems, Reference Snijdewind, van Tol, Onwuteaka-Philipsen and Willems2018). As pointed out by Silvius et al. (Reference Silvius, Memon and Arain2019), “An overall shift in health care to patient-centred care and the recognition of patient autonomy as a preeminent value has … created the impetus for legalization of MAID practices.” Autonomy in end-of-life decision making is also valued by patients living with dementia. The federal Parliament and the Quebec National Assembly now face the difficult task of deciding how best to balance the value of personal autonomy, the protection of non-competent patients from receiving MAID against their will, and the anticipated difficulties for health care professionals in implementing advance requests for MAID.

Appendix

Questions from the Survey Assessing Attitudes Towards Extending MAID to Non-Competent Patients (translated from French)

Mrs. Jackson is a 75-year-old retired teacher who was diagnosed with dementia 3 months ago. A few years earlier, Mrs. Jackson’s mother had died with dementia. Although Mrs. Jackson knows that her quality of life could be good in the early stages, she fears losing her capacity to care for herself. She knows that there is currently no cure for her disease.

Together with her loved ones and physician, Mrs. Jackson discusses the health care that she would or would not want to receive in the future. Next, she records her wishes in a document. In this document, she refuses all medical interventions that would prolong her life after she is no longer able to make health-related decisions. She also explicitly requests that a physician end her life when she no longer recognizes her loved ones anymore.

She gives copies of her document to her loved ones. In the following years, she often reminds them and her physician of the wishes she expressed in the document. Her loved ones agree to speak up to ensure her wishes are respected.

Advanced Stage

Six years later, Mrs. Jackson, now 81, cannot take care of herself anymore. She now lives in a long-term care home and is no longer able to make health-related decisions. However, she does not seem uncomfortable and likely has many more years to live. She interacts well with other residents and her relatives when they visit but does not seem to know who they are anymore.

As instructed by Mrs. Jackson, her loved ones show her physician the document in which she asked that a physician end her life when she could no longer recognize her loved ones anymore.

1. To what extent would you find it acceptable for the Government of Quebec to change the current legislation to allow a physician to administer to Mrs. Jackson, at the advanced stage of her disease, a substance that would cause her death in a matter of minutes?

2. Could someone like Mrs. Jackson, at an advanced stage of dementia, be one of your patients?

▯ No ➔ Skip to the next section

▯ Yes

3. If Mrs. Jackson were one of your patients, how likely would you be to personally comply with her advance request and administer to her, at the advanced stage of her disease, a substance that would cause her death in a matter of minutes, if the law allowed?

Terminal Stage

Mrs. Jackson is still unable to make health-related decisions and her physical health has seriously deteriorated. According to her physician, she has reached the terminal stage and only has a few weeks left to live. She is no longer able to feed herself and must now be spoon-fed. For some time now, she has been showing signs of distress. She cries a lot daily, even when surrounded by her loved ones. All efforts to alleviate her pain and anxiety have failed.

Mrs. Jackson’s loved ones remind her physician of the document in which she asked that a physician end her life when she could no longer recognize her loved ones anymore.

4. To what extent would you find it acceptable for the Government of Quebec to change the current legislation to allow a physician to administer to Mrs. Jackson, at the terminal stage of her disease, a substance that would cause her death in a matter of minutes?

5. Could someone like Mrs. Jackson, at the terminal stage of dementia, be one of your patients?

▯ No ➔ Skip to the next section

▯ Yes

6. If Mrs. Jackson were one of your patients, how likely would you be to personally comply with her advance request and administer to her, at the terminal stage of her disease, a substance that would cause her death in a matter of minutes, if the law allowed?