Background

Low back pain is a common chronic condition; 49–90 per cent of adults worldwide experience low back pain in their lifetime (Scott, Moga, & Harstall, Reference Scott, Moga and Harstall2010). In Canada and in the United States, many of these patients will seek treatment through the emergency department (ED) (Canadian Institute forHealth Information, 2012; Waterman, Belmont, & Schoenfeld, Reference Waterman, Belmont and Schoenfeld2012). It has been estimated that low back pain accounts for 4 per cent of visits to the ED among adults (Edwards, Hayden, Asbridge, Gregoire, & Magee, Reference Edwards, Hayden, Asbridge, Gregoire and Magee2017). Most studies that have examined patients presenting to the ED with low back pain have focused on the younger adult population (16–64 years old), or the “working age” population (Diamond & Borenstein, Reference Diamond and Borenstein2006; Nunn, Hayden, & Magee, Reference Nunn, Hayden and Magee2017). However, an information gap exists concerning the specific characteristics, management, and prevalence of the older adult patient population (65 years of age or older) who present to the ED with low back pain. For example, the prevalence of back pain in the older adult patient population is largely unknown; existing estimates range widely from 13 per cent to 50 per cent (Bressler, Keyes, Rochon, & Badley, Reference Bressler, Keyes, Rochon and Badley1999).

The characteristics and management of older adult patients presenting to the ED with low back pain may differ from those of the younger adult population in important ways. For example, previously conducted studies have found that older patients are more likely to be admitted to hospital (Hwang & Platts-Mills, Reference Hwang and Platts-Mills2013; Waterman et al., Reference Waterman, Belmont and Schoenfeld2012). Older patients may be more likely to present with low back pain pathologies associated with age-related co-morbidities (e.g., cancer, osteoporosis, fractures), and may be less likely to present with non-specific low back pain than the middle-aged patient population (Edwards, Reference Edwards2016). Furthermore, the severity and disability associated with low back pain has been shown to increase with age (Edwards, Reference Edwards2016; Hoy et al., Reference Hoy, Bain, Williams, March, Brooks and Blyth2012). Cognitive and mental health factors such as depression, dementia, anxiety, and insomnia are more commonly associated with low back pain in older adults than in younger adults. For example, one study showed that depressive symptoms predicted disabling low back pain in older adults (Docking et al., Reference Docking, Fleming, Brayne, Zhao, Macfarlane and Jones2011; Weiner, Marcum, & Rodriguez, Reference Weiner, Marcum and Rodriguez2016). Unfortunately, studies suggest that pain, including low back pain, in the older adult patient population is often sub-optimally managed in comparison with pain in the younger adult population (Iyer, Reference Iyer2011; Tarzian & Hoffmann, Reference Tarzian and Hoffmann2004). Pain management for back pain in older adults is particularly challenging, given that common back pain medications can have pronounced adverse effects in this patient population and may be contraindicated in an older population (Kaye, Baluch, & Scott, Reference Kaye, Baluch and Scott2010; Ferrell et al., Reference Ferrell, Casarette, Epplin, Fine, Gloth and Herr2002). For example, one study found that patients 75 years of age or older were 19 per cent less likely to receive pain medication than were adults 35–54 years of age (Platts-Mills et al., Reference Platts-Mills, Esserman, Brown, Bortsov, Sloane and McLean2012). Another study found that adults 65–79 years of age with back pain were 8 per cent less likely to receive analgesia than those 65 years of age or younger (Mills, Edwards, Shofer, Holena, & Abbuhl, Reference Mills, Edwards, Shofer, Holena and Abbuhl2011). This may be especially impactful where previous studies have found that the prevalence of disabling back pain increases with age (Docking et al., Reference Docking, Fleming, Brayne, Zhao, Macfarlane and Jones2011).

Furthermore, older adults with back pain may be inappropriately imaged at a higher proportion in the ED. For example, authors of one study found that in that adults older than 65 years of age were nearly twice as likely as younger adults to receive imaging for low back pain. However, the same authors also found that the presence of a serious spinal pathology was only slightly higher in older adults than in younger adults (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, MacHado, Shaheed, Lin, Needs and Edwards2019). In addition, older adults are at higher risk for experiencing adverse events after ED visits than are younger adults (Aminzadeh & Dalziel, Reference Aminzadeh and Dalziel2002).

For Canadian EDs, age is integrated into the principles that guide management of low back pain. Therefore, it is important to research differences in age group based management of adults. Research to understand and describe the characteristics and management of this older adult patient population and potential differences with younger adults will help inform better management of older adults in the ED.

The purpose of this investigation was to (1) determine the prevalence and characteristics of older adults presenting to the ED with low back pain, (2) compare characteristics to a younger adult patient population to identify age-group-based differences, and (3) compare age-group- based management outcomes in the older and younger adult populations.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional analysis with data collected from the Emergency Department Information System (EDIS) database from the Charles V. Keating Emergency and Trauma Centre (QEII ED) in Halifax, Nova Scotia (July 15, 2009 to June 15, 2018). The QEII ED is a tertiary care teaching hospital and the largest ED in Atlantic Canada. The EDIS database is an integrated information system used in the QEII ED to capture patient visit data. This study was reviewed and approved by the Nova Scotia Health Authority Research Ethics Board.

Study Population

The eligible population included all adults who presented to the QEII ED from July 15, 2009 to June 15, 2018 with a presenting complaint of “back pain” or “traumatic back/spine injury”. Adults were defined as individuals 16 years of age and older (the minimum age of intake in this ED). In accordance with age definitions used by the Canadian government and other research focused on this population group, older adults were defined as patients 65 years of age and older, whereas younger adults were defined as those 16–64 years of age (Giasson, Queen, Larkina, & Smith, Reference Giasson, Queen, Larkina and Smith2017). For select analyses, we created a third age category, oldest old adults, defined as those aged 80 years of age and older. We excluded patients dead upon arrival. Repeat visits by patients were considered to be independent visits.

Variables of Interest

We described two main types of variables for our patient populations: patient and management variables, and diagnostic variables.

Patient and management variables

Variables collected included patient characteristics (age, sex, whether or not they had a primary care clinician, postal code, method of arrival), low back pain presentation characteristics (presenting complaint, presenting level of pain, Canadian Triage and Acuity Scales [CTAS] scores, type and time of ED visit), and management characteristics (admissions, specialist consults, person responsible for payment, and patient left against medical advice status). Patients were defined as having a primary care clinician if the name of a primary care clinician was listed for the patient at the time of ED registration. Postal codes were analyzed by forward sortation area to categorize patients by proximity to the QEII ED (within or outside of the Halifax metropolitan area). A description of all variables captured is presented in Appendix A.

Diagnostic variables

We categorized all eligible patients based on their diagnosis, using International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9/10 codes (Appendix B). Our six definitions of low back pain diagnosis were:

-

1) Non-specific low back pain: pain not attributable to an identifiable specific pathology; pain, muscle tension, or stiffness localized below the lower edge of the chest and above the upper thigh

-

2) Non-specific low back pain with co-morbidity: presenting with a primary complaint of back pain, but subsequently diagnosed with a condition assumed to be co-morbid (e.g., patient presents after slip or fall with main complaint of low back pain but leaves with wrist fracture diagnosis)

-

3) Non-specific low back pain with psychosocial co-morbidity: psychosocial co-morbidity (e.g., patient presents with main complaint of low back pain but leaves with social, cognitive, or mental health diagnosis)

-

4) Low back pain with nerve root irritation: includes neurological signs and symptoms, including irritation/compression of a lumbar nerve root

-

5) Low back pain with underlying medical/surgical pathology: presenting with a primary complaint of back pain, but subsequently diagnosed with another etiology, of which low back pain may be a symptom (e.g., aortic aneurysm or urinary tract infection presents with low back pain)

-

6) Non-lumbar back pain: thoracic or cervical non-specific pain syndromes with or without nerve root irritation

Remaining patients with other diagnostic codes were classified as “unsure”.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated crude prevalence rates for all adults presenting with a complaint of low back pain, and for our older and younger adult age groups. We also calculated the frequencies for each of our defined diagnosis groups listed for younger (16–64), older (65–79), and oldest old (≥ 80) age groups. We further analyzed the “Low back pain with underlying medical/surgical pathology” group by specific diagnosis frequency for each age category.

We described patient characteristics for our older and younger adult age groups presenting with low back pain. We described categorical variables with frequencies and percentages and continuous variables as means and standard deviations, or medians and inter-quartile (IQR) ranges. We tested the data for normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test; for variables that were found to be normally distributed we used means, and for variables that were found to be non-normally distributed, we used medians. We tested the significance for differences found between variables for the older adult and those for younger adult groups. We tested for significance using the two-sample t test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables.

We analyzed the number of older and younger adults who presented with low back pain based on whether they resided inside or outside of the Halifax Metropolitan area, using postal code data and based on the Statistics Canada definition provided previously.

We used multivariable logistic regressions for categorical variables and multivariable linear regressions for continuous variables, controlled for sex, type of presentation, triage score, and self-rated pain. For patients diagnosed with non-specific low back pain, we analyzed the differences in management outcomes (admission, length of stay, and consultation with a specialist) based on age.

Analyses were conducted using STATA IC 14.2.

Results

Population Characteristics

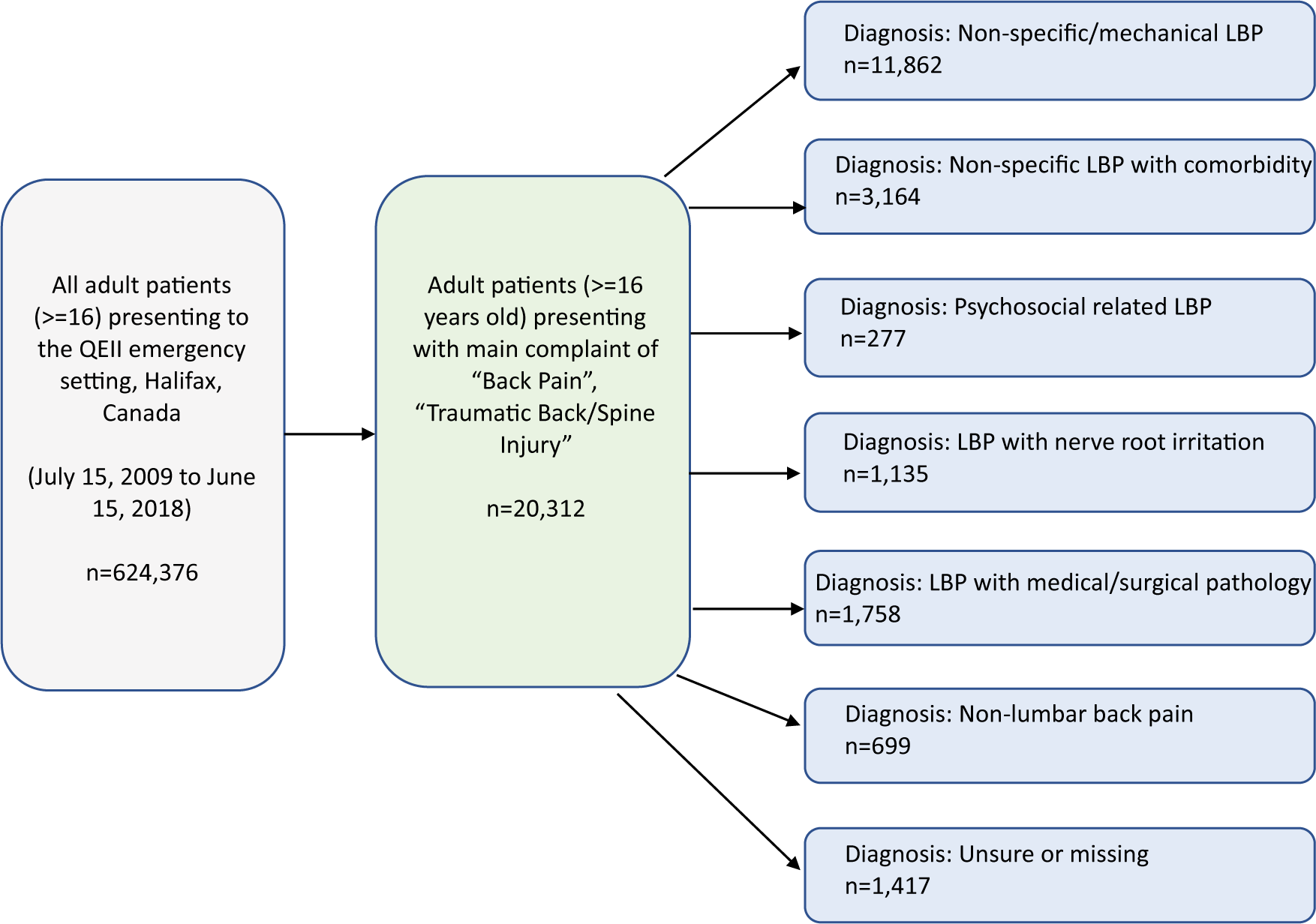

There were 624,376 total presentations to the QEII ED during our study periods, of which 20,312 were for back pain (3%) (see Figure 1 for flow diagram of patient population). Of the total back pain presentations over our study period, 4,030 were patients 65 years of age or older (19.8%) and 16,282 were younger adults (80.2%). Older adults presenting with a complaint of back pain represented 2.9 per cent of all presentations by older adults over the time period, and, similarly, younger adults presenting with a complaint of back pain represented 3.4 per cent of all presentations to the ED by younger adults.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of patient population selection

Older Adult Patient (≥ 65 Years; n = 4,303)

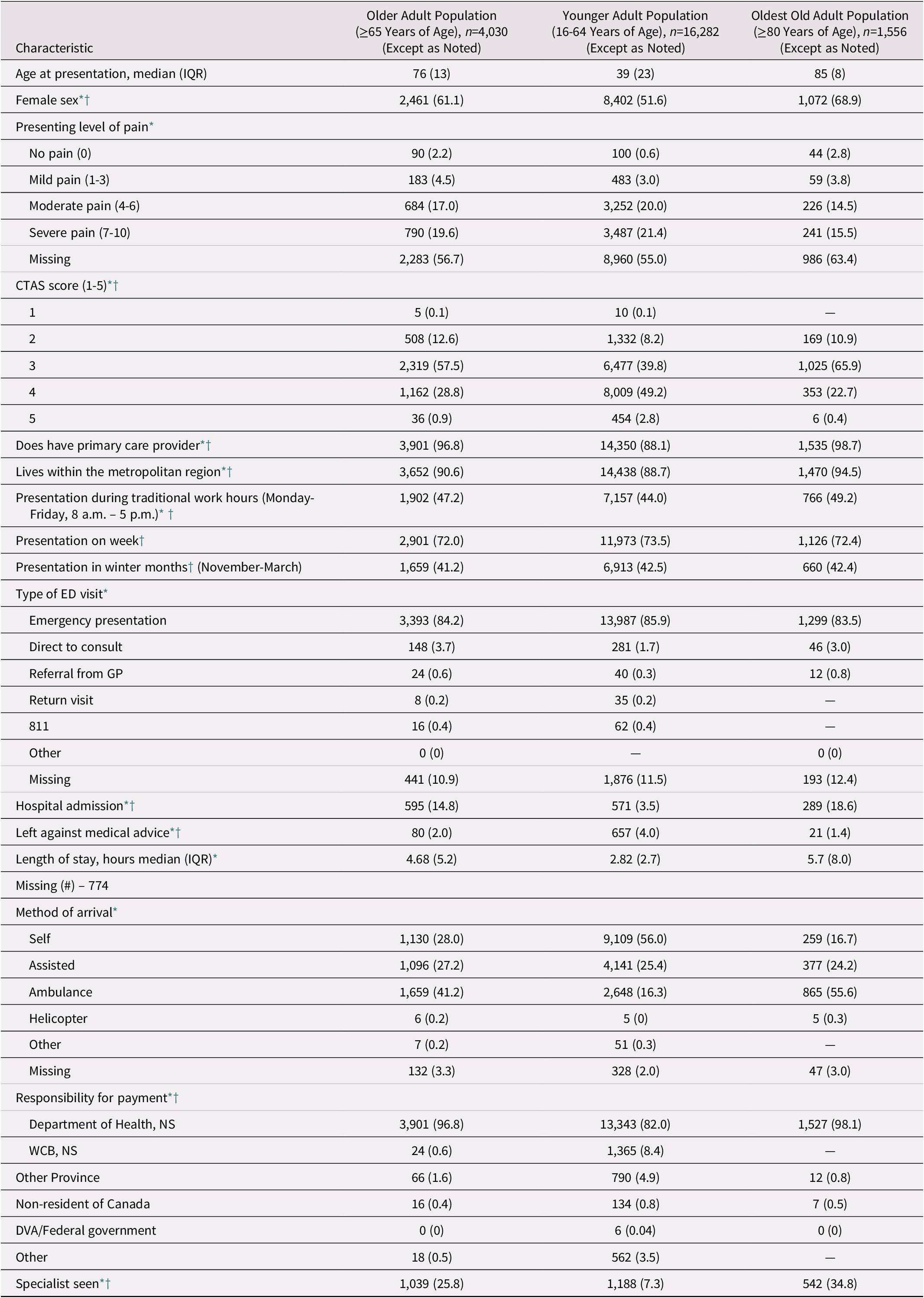

Older adult patients (65 years of age and older) presenting to the ED with back pain had a median age of 76 (IQR = 13), and more than 61 per cent of these patients were female (Table 1). In terms of transportation, 41 per cent of older patient arrived via emergency medical services and 28 per cent arrived on their own. Out of the possible pain groups, patients most frequently self-reported their back pain as severe (20%) and the majority of patients were assigned a CTAS score of 3, or urgent (58%). Older patients presenting to the ED with back pain had a median length of stay in the ED of 5 hours. Fifteen per cent of older patients presenting to the ED with back pain were admitted to the hospital.

Table 1. Characteristics for older and younger adult patients with presenting complaint of back pain

Note. *Differences between the older adult and younger adult groups are statistically significant at the p < 0.001 level.

† Less than 2% of missing data.

Cells containing “—” indicate a cell size smaller than 5 and are not reported.

IQR = inter-quartile range; CTAS = Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale; ED = emergency department; GP = general practitioner; WCB = Workers Compensation Board; DVA = Department of Veterans Affairs.

Oldest Old Adults (≥ 80 Years; n = 1,556)

Patients 80 years of age and older (oldest old adults) had characteristics similar to those of the older adult population (65 years and older). A total of 1,556 oldest old adults presented to the ED with a complaint of back pain over the time period. These patients had a median age of 85 (IQR = 8), and the majority were female (69%). Additionally, the majority arrived via emergency medical services (56%). Upon triage, patients most frequently self-reported their back pain as severe out of each possible pain group (16%). The majority of these patients were assigned a CTAS score of 3 (urgent) (66%). The median length of stay was nearly 6 hours and the majority of oldest old adult patients with low back pain were not admitted to the hospital (81%). Nineteen percent of these patients were admitted to the hospital.

Comparison with Younger Adult Patients (16–64 Years Old)

There were significantly fewer females in the younger adult group (52%) than in the older adult group (65 years and older) (61%). For transportation, significantly more older adults (41%) arrived by ambulance than did younger adults (16%). Oldest old adults (80 years and older) had the greatest percentage of missing data on the presenting level of pain at triage (63.4%), as compared with younger and older adults who had similar percentages of missing data (55% and 56.7% respectively). Similarly to older adults, younger adult patients most frequently self-reported their back pain as severe; however, the majority of younger adults were given a CTAS score of 4 (less urgent), whereas the majority of older adults were assigned a 3 (urgent). Significantly fewer younger adults (3.5%) were admitted to the hospital than older adults (15%). Younger adults had a significantly shorter length of stay (3 hours) than older adults (5 hours).

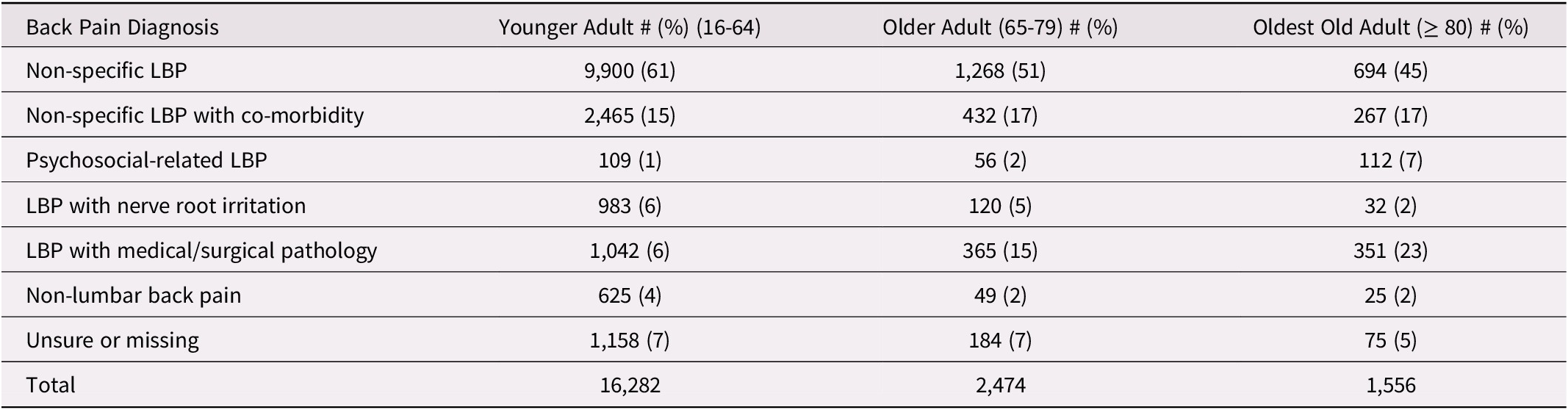

Low Back Pain Diagnoses: Comparison of Older (65–79 Years), Oldest Old (≥ 80 Years), and Younger Adults (16–64 Years)

Over our study period, the most common diagnosis for older, oldest old, and younger adults presenting to the ED with back pain was non-specific low back pain (Table 2). However, younger adults were more frequently (61%) diagnosed with non-specific low back pain than were older adults (51%). Older adults were more frequently diagnosed with low back pain with medical/surgical pathology (15%), as well as low back pain associated with co-morbidity (17%), and low back pain related to psychosocial factors (2%) than were younger adults. Although psychosocial-related low back pain only accounted for a very small proportion of diagnoses overall, oldest old adults were diagnosed three times as frequently under this category than were older or younger adults.

Table 2. Low back pain (LBP) diagnosis by frequency from July 15, 2009 to June 15, 2018

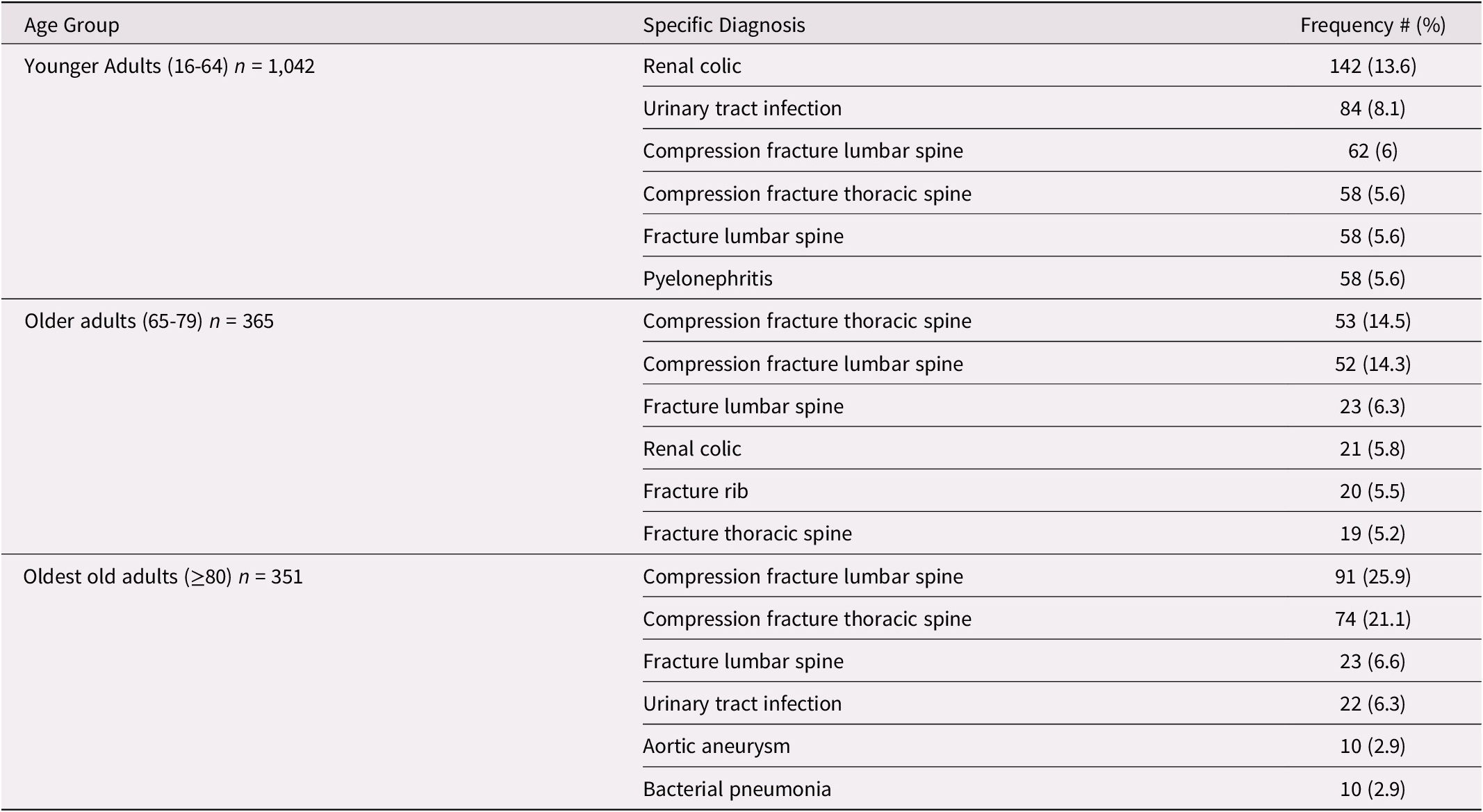

Within the low back pain with medical/surgical pathology category, older adults and oldest old adults were more frequently diagnosed with vertebral compression fractures than were younger adults, whereas younger adults were most frequently diagnosed with renal problems (Table 3). Although compression fractures were the leading diagnosis in older and oldest old adults alike, oldest old adults were more frequently diagnosed with fractures than were older adults.

Table 3. Most common specific diagnoses for patients presenting to the ED with a primary complaint of low back pain classified as “low back pain with medical/surgical pathology”

Note. The number of participants available is noted for each age group category.

Within the low back pain associated with co-morbidity category, all three age groups were most frequently diagnosed with back contusions, yet the oldest old adults were most frequently diagnosed with contusions in different areas, such as the ribs and buttocks.

Non-Specific Low Back Pain Management for Older (65–79 Years), Oldest Old (≥ 80 Years), and Younger Adults (16–64 Years)

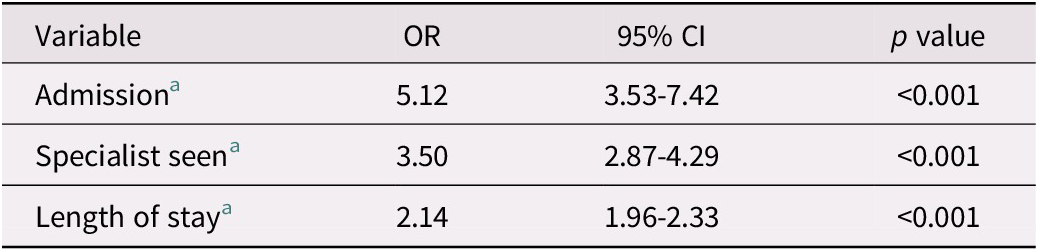

In terms of age-group-based differences in the management of adults diagnosed with non-specific low back pain, the odds of older adults being admitted to the hospital were 5.1 (confidence interval [CI] = 3.53–7.42; p < 0.001) times greater than for younger adults (Table 4). The odds of older adults seeing a specialist was 3.5 (CI = 2.87–4.29; p < 0.001) times greater than for younger adults, and the length of stay for older adults was 2.1 (CI = 1.96–2.33; p < 0.001) times greater than for younger adults.

Table 4. Odds ratios (OR) for older adults (≥ 65 years of age) compared with younger adults (16-64 years of age) diagnosed with non-specific low back pain (LBP)

Note. aControlled for sex, visit type, Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) score, and presenting level of pain.

CI = confidence interval.

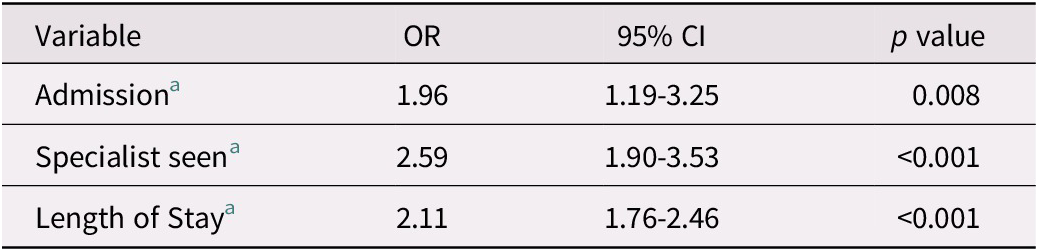

We found no significant difference in the odds of being admitted between oldest old adults and older adults (Table 5). The odds of seeing a specialist were 2.6 (CI = 1.90–3.53; p < 0.001) times greater for oldest old adults than for older adults, and the ED length of stay was 2.1 (CI = 1.76–2.46; p < 0.001) times greater for oldest old adults than for older adults.

Table 5. Odds ratios (OR) for oldest old adults (≥ 80 years of age) compared with older adults (65-79 years or age) diagnosed with non-specific low back pain (LBP)

Note. aControlled for sex, visit type, Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) score, and presenting level of pain.

CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study published that has examined prevalence of back- pain-specific complaints in older adults in an ED setting. This study supports existing evidence that approximately 3 per cent of adults 16 years of age and older who present to the QEII ED present with back pain (Edwards, Hayden, Asbridge, & Magee, Reference Edwards, Hayden, Asbridge and Magee2018). For older adults specifically, back pain represented approximately 3 per cent of all complaints to the ED. Previous research has examined ED presentations of older adults with musculoskeletal complaints. For example, studies found that musculoskeletal pain represented nearly 5 to 6 per cent of all emergency presentations for older adults (65 years and older) (Fayyaz, Khursheed, Mir, & Khan, Reference Fayyaz, Khursheed, Mir and Khan2013; Fry, Fitzpatrick, Considine, Shaban, & Curtis, Reference Fry, Fitzpatrick, Considine, Shaban and Curtis2018). This suggests that our back pain prevalence findings align well with previous research on older adults presenting with musculoskeletal pain.

We analyzed 4,030 presentations of older adults and 16,282 presentations of younger adults with back pain to the ED from 2009 to 2018. The vast majority of patients in both age groups resided in the Halifax metropolitan area. In 2016, nearly 19 per cent of adults (age 16 and older) residing within the Halifax metropolitan area were older adults (Census Profile 2016 Census – Halifax [Census metropolitan area], Nova Scotia and Nova Scotia [Province], n.d.). In our study population, older adults accounted for approximately 20 per cent of all adult back pain complaints in the ED, suggesting that there is proportional use of the ED for back pain by this cohort. This contradicts previous research that demonstrates that older adults use the ED more frequently than younger adults (Latham & Ackroyd-Stolarz, Reference Latham and Ackroyd-Stolarz2014; Legramante et al., Reference Legramante, Morciano, Lucaroni, Gilardi, Caredda and Pesaresi2016). However, back pain prevalence has been reported to be highest in working middle-aged adults, (Dionne, Dunn, & Croft, Reference Dionne, Dunn and Croft2006) which may account for similar frequencies of presentations to the ED in both age groups.

The majority of patient-perceived pain scores were undocumented at triage for all age groups. However, pain scores were most frequently undocumented for oldest old adults. This finding is consistent with other research, in which older age was similarly associated with decreased pain score documentation (Iyer, Reference Iyer2011). We found that both older and younger adults most frequently self-described their presenting level of pain as severe out of all self-reported pain categories (20%, 21%, respectively); however, the severity of pain did not increase with age. This is in contrast with previous research demonstrating that back pain severity increases with age (Dionne et al., Reference Dionne, Dunn and Croft2006). Undocumented pain scores could be contributing to this discrepancy. Other explanations include the fact that older adults often do not report accurate pain scores out of fear of opioids, polypharmacy, or poor assessment (Auret & Schug, Reference Auret and Schug2005). Our findings suggest that older adults, although more likely to have a pathological cause of back pain, continue to report similar levels of pain as younger adults.

Although pain severity was similar across age groups, older adults were frequently assigned a more urgent CTAS score than were younger adults. The assignment of a more urgent triage score being associated with increasing age has been found in other studies (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Oh, Peck, Lee, Park and Kim2011; Legramante et al., Reference Legramante, Morciano, Lucaroni, Gilardi, Caredda and Pesaresi2016). For example, one study found that 8.5 per cent of older adults and 3 per cent of younger adults were given the highest acuity triage score (Legramante et al., Reference Legramante, Morciano, Lucaroni, Gilardi, Caredda and Pesaresi2016). This discrepancy likely reflects increased incidence of complexity of care in the older adult population, which could lead older adult patients to be assigned a more urgent triage score for the same self-reported severity as younger adults. In addition, this finding could be partially explained by the “frailty modifier” that was added to a 2016 revision to the CTAS guidelines. With this modifier, patients assessed as frail (patients who were dependent on personal care, were wheelchair bound, had a cognitive impairment, were terminally ill, who showed signs of cachexia and weakness, or were over the age of 80 years), were automatically triaged as at a CTAS level 3 or higher (Bullard et al., Reference Bullard, Musgrave, Warren, Unger, Skeldon and Grierson2017).

The most frequent cause of low back pain is known to be non-specific, which was true for all three of our adult patient groups (Wong, Karppinen, & Samartzis, Reference Wong, Karppinen and Samartzis2017). However, increased age was associated with more frequent diagnosis of low back pain with underlying medical/surgical pathology (indicating a pathologic cause for the back pain). This trend demonstrates that as patients age, they are more likely to have a serious pathology underlying their back pain symptoms. This may be the result of the accumulation of age-related co-morbidities over time, including the increased susceptibility for falls, which would put older adults at greater risk for fractures (Jones, Pandit, & Lavy, Reference Jones, Pandit and Lavy2014). The prevalence of vertebral compression fractures increases with age, especially in females 80 years of age and older (Melton et al., Reference Melton, Kan, Frye, Wahner, Michael O’fallon and Riggs1989). Compression fractures were the most common diagnoses of pathologic low back pain in older and oldest old adult populations.

Given that the most common diagnosis of low back pain was non-specific in all of our study populations, current back pain intervention guidelines may need to be reviewed. For example, Canada’s Choosing Wisely group considers new back pain in adults over 50 to be a red flag, which prompts imaging in the ED (Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians, 2018). However, the majority of patients in these age groups are ultimately diagnosed with non-specific low back pain. Research has demonstrated that automatically including early imaging in the management of older adults with low back pain does not necessarily lead to better health outcomes. For example, one study found that older adult patients who had early imaging reported the same level of pain and disability over the next year as those who had not undergone early imaging (Jarvik et al., Reference Jarvik, Gold, Comstock, Heagerty, Rundell and Turner2015). Therefore, future research should examine current imaging practices in the ED for patients ultimately diagnosed with non-specific low back pain and consider whether these guidelines remain appropriate.

We focused on the non-specific low back pain diagnosis group to identify age-group- based differences in management outcomes. We found that the rates of admission and length of stay were increased for older adults. Other studies have found similar results (Keskinoğlu & İnan, Reference Keskinoğlu and İnan2014). For example, one study found that for patients presenting to an ED for any complaint, older adults were hospitalized nearly three times as frequently as younger adults (Legramante et al., Reference Legramante, Morciano, Lucaroni, Gilardi, Caredda and Pesaresi2016). Another study found that the median length of stay for those 65–74 years of age was 4.4 hours and reached 5.9 hours in those 85 years of age and older (Latham & Ackroyd-Stolarz, Reference Latham and Ackroyd-Stolarz2014). Admission rates and length of stay may be increased for older adult patients diagnosed with non-specific low back pain for different reasons, such as having multi-system disorders, atypical presentations, and psychosocial challenges. Importantly, hospital admission and longer length of stay are associated with poor outcomes for older adults (García-Peña et al., Reference García-Peña, Pérez-Zepeda, Robles-Jiménez, Sánchez-García, Ramírez-Aldana and Tella-Vega2018; Singer, Thode, Viccellio, & Pines, Reference Singer, Thode, Viccellio and Pines2011). Options other than admission should be considered; such as intermediate care and community-based care, which have been proposed as alternatives to acute care for older adults with non-urgent issues (Andrew & Rockwood, Reference Andrew and Rockwood2014). In addition, future research should concentrate on identifying ways to decrease length of stay for the most vulnerable of the older adult population.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this analysis include its large sample size over many years. In addition, we provide a detailed perspective of different back pain diagnostic categories and outline the most specific back pain pathologies.

Our limitations include potentially underestimating the prevalence of low back pain diagnoses in the ED. Our data set captures only those whose primary complaint was back pain; it excludes those who had a different primary complaint, but were discharged with a diagnosis of low back pain. In addition, the accuracy of the presenting and diagnostic ICD codes used in this database is currently unknown. In addition, there was missing information for some variables within the database, which may have affected overall study results (see Table 1 for variables that contained missing data). For example, more than half of the presenting level of pain scores were missing for the oldest old adults. Complete information may have rendered different results. Our study analysis was limited to the variables available in our data set; as such, we did not have information on important patient management factors such as presence of co-morbidities; use of diagnostic imaging; medications administered prior to arrival, during, or after the visit to the ED; or any other interventions. These management and outcome variables are important aspects in the clinical picture of care for older adults with back pain. As such, we recommend that future research focuses on these variables to create a richer clinical picture.

Finally, and importantly, the age ranges for the age groupings in this study are large. This has several implications; for example, it generalizes all “older adults”, 65 years and older, to have the same general health issues. In reality, individual health status depends on much more than age alone and it may be harmful to homogenize the management of older adults based on these broad age groupings. We recommend future research examine smaller age groupings, such as 5 or 10 years. Finally, given that this study is a retrospective analysis from a single institution, it may lack generalizability to other settings.

Conclusions

We have presented a full description of the patient characteristics and management differences between younger and older adults with low back pain who present to the ED. Our study found that non-specific low back pain remained the most frequent diagnosis across all age groups. Older adults were more frequently diagnosed with pathological causes for their back pain; an effect that intensifies with increased age. However, contrary to previous research, back pain severity did not increase significantly with age. We found that older adults have increased ED length of stay and increased chance of being admitted to the hospital and of being seen by a specialist. This may reflect that older adults, especially the oldest old adults, have unique needs in the ED because of inter-related social, medical, and functional issues that often increase with age. These patterns of management can be used to set the stage for future studies on resource planning. Future research on this topic should concentrate on gathering further details surrounding the management and outcomes of older adults who present to the ED with back pain, such as use of imaging and analgesics, being mindful to include small age groupings in the analysis.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980821000118.