Driven by population trends such as aging, there has been an increasing interest in understanding older workers’ career extension and return-to-work trajectories (Truxillo, Cadiz, & Hammer, Reference Truxillo, Cadiz and Hammer2015; Zacher, Kooij, & Beier, Reference Zacher, Kooij and Beier2018). In Canada, people 65 years of age and older currently represent 18 per cent of the population (Statistics Canada, 2020). Projections indicate that between 21 and 29 per cent of the Canadian population will be 65 years old or older in 2068 (Statistics Canada, 2016).

The twin issues of population aging and critical talent shortages are leading employers to encourage older workers to prolong their professional lives (Latulippe, St-Onge, Gagné, Ballesteros-Leiva, & Beauchamp-Legault, Reference Latulippe, St-Onge, Gagné, Ballesteros-Leiva and Beauchamp-Legault2017; Polat, Bal, & Jansen, Reference Polat, Bal and Jansen2017). Since the start of the 1990s, older workers whose health condition allows them to increasingly postpone their retirement desire to remain active longer (Bélanger, Carrière, & Sabourin, Reference Bélanger, Carrière and Sabourin2016). This decision may be prompted by extrinsic motivations such as financial needs (e.g., indebtedness, mortgage) or intrinsic ones (e.g., need for fulfillment).

Although it is clear that the population is aging, the aging of the workforce varies depending on employers’ particular characteristics (e.g., past hiring patterns, compensation practices, employment policies, production technology) as their responses to workforce aging differ across industries and occupations (Clark, Nyce, Ritter, & Shoven, Reference Clark, Nyce, Ritter and Shoven2019). The skills shortage appears to be a particular challenge in the finance and insurance sector (hereafter referred to as the financial services sector), given its high employee turnover rate, especially among professionals (Conseil Emploi Métropole, 2013). Employers in the financial services sector are faced with particular demographic, talent, and technological pressures and, more recently, artificial intelligence challenges (Conseil Emploi Métropole, 2018). According to a ManpowerGroup survey involving 41,700 employers in 40 countries, accounting and financial positions are among the 10 most challenging to fill (ManpowerGroup, 2015). Given the advances in the artificial intelligence domain, organizations in the financial services sector are compelled to revise their business model, job-required skills, and the ways that operations and processes are conducted. For example, the less complex tasks may be computerized, digitized, or automated so that the professionals may undertake new roles and responsibilities with higher added value, to provide better services at a lesser cost (Crosman, Reference Crosman2018; Langlois, Féral-Pierssens, Leduc, Vézeau, & Tagnit, Reference Langlois, Féral-Pierssens, Leduc, Vézeau and Tagnit2017).

Consequently, it might be crucial to encourage older finance professionals to prolong their working lives. Employers can motivate them by reviewing their total rewards, defined as all the characteristics that they value in their jobs, including monetary rewards, benefits, career development, and work content and context (St-Onge, Reference St-Onge2020; WorldatWork, 2015). Adopting a total rewards strategy based on workforce characteristics provides employers with a competitive advantage in terms of their value proposition (Gross & Rook, Reference Gross, Rook, Berger and Berger2018) and being perceived as employers of choice (St-Onge, Reference St-Onge2020).

However, we do not know the extent to which top executives are trying to revise their practices to accommodate their older professionals and how they are doing so. A literature review published in Canadian Public Policy concludes that there is a lack of knowledge regarding the effects of management practices on the attraction and retention of older workers (Bélanger et al., Reference Bélanger, Carrière and Sabourin2016). Similarly, Pak, Kooij, De Lange, and Van Veldhoven (Reference Pak, Kooij, De Lange and Van Veldhoven2019, p. 1) point out that “organizations are challenged to extend the working lives of older workers. However, there is little empirical evidence available on how organizations should do this”. To address this research gap, we interviewed executives in the financial services sector to explore which conditions need to be met and how total rewards could be managed to keep older professionals working longer. More precisely, our research question is the following: In the eyes of employers in the financial services sector, which total reward strategies will motivate their older professionals to extend their working lives?

The contributions of this study are manifold. First, the present study adopts an organizational perspective to understand better the relationship between older workers’ total reward components and workforce retention. To date, most authors have used an individual approach to examine older employee management (see the review of Truxillo, Cadiz, & Rineer, Reference Truxillo, Cadiz and Rineer2014). Taking an employer’s perspective appears even more critical, given that the majority of older workers report that they would prolong their professional lives if their employer agreed to adapt their job and work context. Pak et al. (Reference Pak, Kooij, De Lange and Van Veldhoven2019, p. 12) conclude their systematic review thus: “More research is needed on which actions organizations can take to improve employability, the motivation to continue working and especially the opportunity to continue working.” Meeting this need is critical because an increasing number of older workers wish to continue working, either to fulfil psychological needs, in line with continuity theory (Atchley, Reference Atchley1989), or because they cannot financially afford to stop working (Kulik, Ryan, Harper, & George, Reference Kulik, Ryan, Harper and George2014).

Second, this study responds to a need expressed by several authors to analyze older employee management in particular sectors or industries (Armstrong-Stassen & Schlosser, Reference Armstrong-Stassen and Schlosser2011; Truxillo et al., Reference Truxillo, Cadiz and Hammer2015). As Tremblay and Genin (Reference Tremblay and Genin2009, p. 183) put it “The reasons that people would stay in employment longer depend on the type of job. Consequently, governments and organizations will probably have to adopt a contingent approach, i.e., all incentives do not necessarily fit all jobs or all sectors”. Hence, we focused on the employment retention of older professionals in the financial services sector, a group of people who tend to be highly qualified, well paid, and subject to specific pressures (e.g., technological, competitive); this group has been insufficiently investigated. To our knowledge, this study is the first one to explore older worker retention in the financial services sector, a fast-changing, knowledge-intensive technology sector that Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers, and de Lange (Reference Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers and de Lange2014) recommend as “an extreme case” for a qualitative study.

Third, to our knowledge, this study is also the first to explore how executives envisage, interpret, and enact the management of older professionals and how this affects their total rewards policies and their organizational climate. We use Boxall and Purcell’s (Reference Boxall, Purcell, Wilkinson, Gollan, Marchington and Lewin2011) “black box” model of human resource management (HRM) that takes into account the particularity of each firm and its industry. Such a conceptualization is of added value, because more than half of the prior studies on the extension of working life have not used any theory (see the review of Pak et al., Reference Pak, Kooij, De Lange and Van Veldhoven2019). The artificial intelligence advances may induce technological unemployment, increase social inequalities, and require workers with new skills (Boyd & Holton, Reference Boyd and Holton2018). In such a context, the issue is whether and how executives’ support in the financial services sector might be more or less conducive to prolonging older professionals’ active life.

Finally, the study results are significant on a societal level, given the importance of the financial services sector in the job market of the economies of developed countries. According to the Global Financial Centers Ranking, growth in the financial services sector ranks 12th globally (Langlois et al., Reference Langlois, Féral-Pierssens, Leduc, Vézeau and Tagnit2017). In Canada, for example, although the financial services sector represents 6.7 per cent of the economic activity, measured by gross domestic product (GDP), and 4.7 per cent of total employment in the private sector, employees in this sector receive 9 per cent of the compensation paid (Langlois et al., Reference Langlois, Féral-Pierssens, Leduc, Vézeau and Tagnit2017).

This article is structured as follows. First, we summarize the literature on the HRM practices or total rewards components that influence older workers’ retention in organizations. Second, we describe the theoretical foundations of our study, the black box model of HRM, to explain the crucial importance of top management support on the organizational climate and the prevalence of total rewards components that favor retaining older finance professionals at work. Next, we present the study methodology and results, followed by the discussion and implications of this research.

Literature Review and Theoretical Foundations

This section first reviews the previous literature to summarize what total reward components that older employees value. This review aims at helping us identify what leads older employees to prolong their working lives and what employers could do to support them. Next, we introduce Boxall and Purcell’s (Reference Boxall, Purcell, Wilkinson, Gollan, Marchington and Lewin2011) black box model of HRM to understand better which total reward strategies are more likely to motivate older employees to prolong their working lives.

Total Rewards Components and the Retention of Older Workers

To date, researchers have mainly used a conceptual framework based on an individual perspective (see the reviews of Pak et al., Reference Pak, Kooij, De Lange and Van Veldhoven2019; Truxillo et al., Reference Truxillo, Cadiz and Hammer2015; Zacher et al., Reference Zacher, Kooij and Beier2018) to study older employees’ career management decisions. More specifically, they investigated bridge employment (Saba, Reference Saba, Alcover, Cantisano, Depolo, Fraccaroli and Parry2014); that is, the various forms of work preceding permanent retirement (part-time jobs, self-employment, temporary contracts) (Wang & Shultz, Reference Wang and Shultz2010). These earlier studies have mostly been aligned with the attraction/selection/attrition (ASA) model (Schneider, Goldstiein, & Smith, Reference Schneider, Goldstiein and Smith1995), suggesting that employees prefer to work for organizations and hold jobs offering rewards and working conditions that are consistent with their characteristics (e.g., values, age).

More recently, other individual theoretical frameworks based on older workers’ motivation (Kanfer, Beier, & Ackerman, Reference Kanfer, Beier and Ackerman2013), the lifespan theory of selection, optimization, and compensation (Baltes, Staudinger, & Lindenberger, Reference Baltes, Staudinger and Lindenberger1999), and the abilities–motivation–opportunity (AMO) theory (Appelbaum, Bailey, Berg, Kalleberg, & Bailey, Reference Appelbaum, Bailey, Berg, Kalleberg and Bailey2000) have been suggested. Studies over the past two decades have mostly examined which HR practices influence older workers’ ability, motivation, and opportunity to continue working through the use of HRM (Armstrong-Stassen, Reference Armstrong-Stassen2008; Kooij et al., Reference Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers and de Lange2014; Mansour & Tremblay, Reference Mansour and Tremblay2019; Saba & Guerin, Reference Saba and Guerin2005; Truxillo et al., Reference Truxillo, Cadiz and Rineer2014). Recently, Kooij et al. (Reference Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers and de Lange2014) have identified four types of such practices: (1) developmental practices that help older workers reach higher levels of functioning, (2) maintenance practices that help them maintain their current levels of functioning, (3) utilization practices that use the various competencies of older workers and might be used to help them return to their previous levels of functioning after experiencing a loss, and (4) accommodative practices that help workers function at lower levels when maintenance and recovery are no longer possible.

Based on these studies and previous reviews of them, we might group total reward components into four broad categories: (1) flexibility in work content and organization, (2) skills development and use, (3) compensation (direct and indirect) and recognition practices, and (4) inclusive culture and work climate.

Flexibility in work content and organization

Empirical and theoretical studies suggest offering older employees various means of accommodation to encourage them to continue working. First, work content (e.g., load, rhythms, duties) may be modified, along with performance expectations and demands from a physical, emotional, or temporal perspective (e.g., exemption from working overtime or night shifts, additional leave, prolonged career interruptions) (Guérin & Saba, Reference Guérin and Saba2003; Tremblay & Genin, Reference Tremblay and Genin2009). Studies have shown that employers used such accommodation practices (Kooij et al., Reference Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers and de Lange2014; Pak et al., Reference Pak, Kooij, De Lange and Van Veldhoven2019; Remery, Henkens, Schippers, & Ekamper, Reference Remery, Henkens, Schippers and Ekamper2003) to reduce work demands so that older workers could maintain adequate productivity. For example, voluntary downgrading may reduce the fatigue or stress of older employees who turn to less physically or mentally demanding work (Josten & Schalk, Reference Josten and Schalk2010). However, experts recommend using it as a last resort and very carefully, as it is associated with reduced work satisfaction and may therefore precipitate their leaving (Josten & Schalk, Reference Josten and Schalk2010; Kooij et al., Reference Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers and de Lange2014).

Many studies also suggest modifying older workers’ working time and place of work through job sharing, accumulation or elimination of overtime, flexible work schedule, shorter or compressed work week, part-year work, shorter hours, part-time work, contract work, or teleworking (full- or part-time) (Alcover & Topa, Reference Alcover and Topa2018; Beier, Torres, Fisher, & Wallace, Reference Beier, Torres, Fisher and Wallace2019; Polat et al., Reference Polat, Bal and Jansen2017; Saba & Guerin, Reference Saba and Guerin2005). Some authors call these practices “retaining” or “accommodative” ones, depending upon whether they help older employees maintain or regain their capacities or work at a lower level (Alcover & Topa, Reference Alcover and Topa2018; Kooij et al., Reference Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers and de Lange2014).

Skills development and use

Studies have shown that employers offer workers over the age of 50 fewer training courses and progress opportunities (Canduela et al., Reference Canduela, Dutton, Johnson, Lindsay, McQuaid and Raeside2012; Karpinska, Henkens, & Schippers, Reference Karpinska, Henkens and Schippers2013), although the workers’ lack of skills is a predictor of their early retirement (Beier et al., Reference Beier, Torres, Fisher and Wallace2019). Organizations offering development opportunities reduce workers’ skills obsolescence and stress related to new skills acquisition (e.g., introduction to new technologies) and signal the value of their presence in the firm (Armstrong-Stassen & Schlosser, Reference Armstrong-Stassen and Schlosser2011). It is not surprising that training and personal and professional growth opportunities positively influence these workers’ motivation to continue working (Chen & Gardiner, Reference Chen and Gardiner2019; Polat et al., Reference Polat, Bal and Jansen2017). Based on the results of their meta-analyses of 83 studies, Kooij et al. (Reference Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers and de Lange2014) and Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers, and De Lange (Reference Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers and De Lange2010) call these “developmental HR practices”, as they help older workers increase and enhance their contribution by offering them training, challenges, and internal promotions.

Older workers are more likely to continue working when they can do so more flexibly through a second career, special assignments such as consulting, training, or mentoring young recruits, or even changing jobs through lateral job movements or task enrichment or rotation (Beehr & Bennett, Reference Beehr and Bennett2015). Such flexibility in their work content when employees are nearing retirement enables them to use their experience and therefore increases their employability. Such HR practices may be said to use older employees’ strengths, or they may be seen as accommodative practices (Kooij et al., Reference Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers and de Lange2014; Pak et al., Reference Pak, Kooij, De Lange and Van Veldhoven2019) in that they help reduce work time or demands so that these employees may continue working. We can place all types of recall of retirees in this category (e.g., ad hoc mandates, vacation replacement, assistance in busy periods, consulting/contingent workers). In the services sector, older professionals are increasingly acting as coaches or mentors during temporary assignments (Burmeister & Deller, Reference Burmeister and Deller2016; Ng & Law, Reference Ng and Law2014). According to many authors (Mansour & Tremblay, Reference Mansour and Tremblay2019; Miranda-Chan & Nakanura, Reference Miranda-Chan and Nakanura2016), knowledge transfer (or generative behaviors) to the next generation offers satisfaction beyond skills development and well-being (Polat et al., Reference Polat, Bal and Jansen2017) and might motivate them to retire later from the workplace.

Direct and indirect compensation and recognition practices

Although older workers may continue working out of financial necessity (Bélanger et al., Reference Bélanger, Carrière and Sabourin2016), the effect of direct and indirect compensation has attracted scant attention. Studies show that older workers value benefits such as pre-retirement programs or leave opportunities (for personal reasons or without pay), longer holidays, health insurance benefits, or perks (e.g., financial advice, retirement advice, membership fee for sports centers) (Armstrong-Stassen, Reference Armstrong-Stassen2008; Guérin & Saba, Reference Guérin and Saba2003; Tremblay & Larivière, Reference Tremblay and Larivière2009). Consequently, employers should consider revising their variable pay schemes or their reward allocation criteria. Working longer would also enable older workers to improve their total compensation by reclassifying their positions or receiving bonuses or non-monetary allowances. To highlight the importance of older workers, organizations may give them greater visibility through the company magazine, intranet or Web site. They might also put forward official means of public recognition (e.g., medals, ceremonies).

Measures may also involve offering them various retirement dispositions (e.g., phased, progressive, or deferred retirement) or the opportunity of continuing work after retirement age (Templer, Armstrong-Stassen, & Cattaneo, Reference Templer, Armstrong-Stassen and Cattaneo2010). It is also important to discuss early retirement schemes. Those emerged during the 1980 recession when many firms employed many workers over 50 years of age, and their retirement scheme held surplus assets. Today, employers still use such programs from time to time to encourage their older workers to take early retirement. They may offer various incentives such as severance pay, removing the pension reduction, eliminating the increase of years of service accrued (St-Onge, Reference St-Onge2020). They may also provide additional bridging benefits or increased pensions.

An inclusive culture and work climate

The culture and work climate, viewed as relating to the broader context (Zacher & Yang, Reference Zacher and Yang2016), is another total reward component that could influence older workers’ decision whether or not to retire. A work climate wherein their contribution is recognized and they are treated with respect is among the main reasons that older workers stay at work (Armstrong-Stassen & Schlosser, Reference Armstrong-Stassen and Schlosser2008). Some researchers report that employees who perceive a hostile climate toward working longer want to retire at an earlier age (Zacher & Yang, Reference Zacher and Yang2016). Similarly, Polat et al. (Reference Polat, Bal and Jansen2017) use a scale measuring the importance of the development climate to show that it significantly influences workers’ motivation to work beyond retirement age. Nevertheless, it appears that age discrimination is most prevalent toward older employees (Snape & Redman, Reference Snape and Redman2003), and a longitudinal study has indicated that for employees over the age of 50, a perceived lack of work recognition increases their propensity to quit or retire (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Hagger-Johnson, Head, Shelton, Stafford and Stansfeld2016).

Although they lack empirical foundation, numerous prejudices and negative stereotypes against older workers (e.g., they are less competent, resist change, have less ability to learn) persist and incite them to retire (Bal, et al., Reference Bal, de Lange, Van der Heijden, Zacher, Oderkerk and Otten2015). Ng & Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2012). It appears that older employees’ increased experience compensates for their age-related performance loss, and even that work performance is positively related to work experience (Kunze, Boehm, & Bruch, Reference Kunze, Boehm and Bruch2013; Lagacé & Terrion, Reference Lagacé and Terrion2013). There is evidence that it is the discrimination strategies and age-based stereotypes found in the processes of selection, management, performance evaluation, and award or promotion grants (see the meta-analysis of Bal, Reiss, Rudolph, & Baltes, Reference Bal, Reiss, Rudolph and Baltes2011) that incite older workers to retire (Canduela et al., Reference Canduela, Dutton, Johnson, Lindsay, McQuaid and Raeside2012).

Employers need to rethink their total reward strategy and re-examine its components. They need to find new solutions to their labor shortage problem and respond to healthy older workers who wish to continue working for various reasons. As early as 2014, more than 40 per cent of the Quebec Pension Plan beneficiaries were still at work, and more than 20 per cent of the pension recipients between 65 and 69 years of age were economically active people (Latulippe et al., Reference Latulippe, St-Onge, Gagné, Ballesteros-Leiva and Beauchamp-Legault2017). To meet the needs of the increasing number of older workers and retain them, it is clear that changes need to be made at the level of support within management and executive teams in the light of the HRM black box model.

The Black Box Model of HRM

Strongly related to the concept of diversity management, seeking to provide a context and work climate favorable to older workers requires organizations to adopt inclusive management practices (Boehm, Kunze, & Bruch, Reference Boehm, Kunze and Bruch2014). At the top management level, we find the key players responsible for developing an inclusive culture and climate in their organizations. Studies have shown that the executives’ attitudes and level of awareness regarding organizational culture influence the strategic orientations (Buttner, Lowe, & Billings-Harris, Reference Buttner, Lowe and Billings-Harris2006) and the climate of openness relating to diversity issues (Booysen, Reference Booysen2014; Zacher & Yang, Reference Zacher and Yang2016,). In addition, executives need to give meaning to the notion of diversity value to influence HR professionals’ attitudes and actions. However, the latter do have some leeway when selecting specific practices (Ng & Sears, Reference Ng and Sears2020). A recent literature review (Chen & Gardiner, Reference Chen and Gardiner2019) shows that inclusive and positive organizational support is positively related to older workers’ remaining at work and actively participating in their firm’s development.

To our knowledge, however, few researchers have sought to uncover how top management values regarding older workers are transmitted and influence their firm’s performance. Boxall, Ang, and Bartram’s (Reference Boxall, Ang and Bartram2011) black box model may be of use. It presents linkages between the goals espoused by top management and a firm’s performance, considering various stakeholders’ perceptions (e.g., executives, middle managers, HR professionals, immediate supervisors). More specifically, this model shows (1) how the values held by executives and the managerial policies they adopt (HR, marketing, finance, operations) lead to (2) management actions (e.g., budgets, HR policies, administrative decisions), (3) which are then interpreted and attributed – both individually and collectively – by employees, (4) whose attitudes and behaviors are in turn influenced, ultimately by (5) having an impact on various organizational results such as productivity, flexibility, legitimacy, financial performance, employee turnover, social responsibility, innovation, agility, and even sustainable employability. Thus, this model appears particularly relevant when it comes to better understanding how executives – both through the values they communicate and the total rewards they adopt – influence older workers’ decisions regarding whether or not to keep working longer.

Moreover, Boxall et al. (Reference Boxall, Ang and Bartram2011) distinguish between the executives’ intention to adopt certain practices and the perceptions and interpretations of these practices by other actors (e.g., employees, managers), depending upon their overall coherence within the organizational context (Bowen & Ostroff, Reference Bowen and Ostroff2004; Lepak, Taylor, Tekleab, Marrone, & Cohen, Reference Lepak, Taylor, Tekleab, Marrone and Cohen2007). The model attaches great importance to the middle-level managers whose task is to interpret the top-level executives’ expectations and decisions and implement the directives they receive (Purcell & Hutchinson, Reference Purcell and Hutchinson2007). The model also stresses the importance of feedback and communication among employees, line managers, and top-level executives to change practices and the corporate culture.

According to Boxall and Purcell (Reference Boxall, Purcell, Wilkinson, Gollan, Marchington and Lewin2011), an organization’s performance is measured not only by its financial results but also by its social legitimacy and the flexibility with which it adapts to environmental challenges. Thus, this model recognizes that in a context of talent scarcity and artificial intelligence development, it is vital for employers in the finance sector to adjust their ways of managing their employees to meet individual, organizational, and societal needs. However, the black box model also posits that even within the same industry, there will be diversity in the goals espoused by top executives and, therefore, various HRM policies according to their organization’s characteristics (values, staff relations, and procedures).

Research findings have emphasized the significance of top management support to ensure the development of a corporate culture open to retaining older workers. This notion involves bringing together all staff members’ perceptions of the fairness of the actions, procedures, and behaviors regarding employees in all age groups (Boehm et al., Reference Boehm, Kunze and Bruch2014). Hence, using the model of the links among the variables in the HRM black box, we intend to explore how the views of management and the support given to older workers in the financial services sector may influence the strategies used and the actions they take, or not. We expect that each firm’s organizational culture or the values held by its executives would affect the type and number of total rewards components adopted to promote the retention of older professionals.

Method

The sample used in this qualitative study was constructed using the snowballing technique to select participants from organizations of various sizes in the financial services sector who could best help us address our research questions (Creswell & Creswell, Reference Creswell and Creswell2017). A professional from Finance MontrealFootnote 1 used his network to assist the research team in identifying executives and soliciting their participation. We obtained an interview with the top management of 16 major organizations in the Quebec financial services sector, located in the Montreal and Quebec City areas (e.g., National Bank, Desjardins, Sun Life Financial, Industrial Alliance, Intact Insurance). Five organizations did not participate, often because of lack of time, or did not answer or follow up on our invitation. Our sample appears relevant because the province of Quebec accounts for 20 per cent of the Canadian share of the insurance sector’s GDP. Montreal’s banking sector includes four financial institutions headquarters: Desjardins, National Bank of Canada, Laurentian Bank, and the Business Development Bank of Canada. Some international banks (BNP Paribas, Société Générale, State Street) have centralized their back-office activities in Montreal.

The participants interviewed were eight directors (HR, talent acquisition, talent management), six vice-presidents, a branch top manager, and a strategic human resources consultant. Depending on the participant’s preference, each interview conducted over the phone or Skype, in French or English, lasted between 45 and 60 minutes. Before the meeting, participants received an e-mail outlining the study’s purpose and providing the semi-structured interview grid and a consent form to sign, in line with ethical guidelines.

The research team members conducted all interviews in tandem. They digitally recorded all interviews. Three members analyzed the transcribed interviews, identifying and coding the dominant themes using an inductive process, and then refined the analysis using a deductive method based on the literature review (Blais & Martineau, Reference Blais and Martineau2006). The content analysis involved three steps. First, the researchers read all transcribed interviews to gain an overall sense of them. Second, they coded them according to pre-established themes prompted by the research questions, the literature review, and the interview protocol, using NVivo 11 qualitative analysis software. This software promoted an in-depth analysis of each interview and compared the participants’ comments to identify dominant and subsidiary themes. Third, the coding system’s initial version was then revised and enriched according to eight main categories and 19 sub-categories. These were determined based on their frequency of occurrence and apparent significance. Last, the researchers selected the most generally representative participant narratives, referring to issues (challenges, obstacles, and total rewards components) identified by more than two participants.

Results

As expected, for our study participants, top management’s explicit support of an inclusive culture appeared to be the critical determinant encouraging older professionals to prolong their professional lives. According to these participants, such support for a culture of openness to diversity was necessary to develop a climate and work conditions conducive to retaining older professionals. They felt that they needed to go beyond existing practices and secure support from top management to create a favorable culture for older workers. As one participant put it,

The fact that top management embraces these changes and believes in them will help change the practices concerning older professionals. It’s easy to make changes in management practices and imagine that, with time, things will evolve, but this rarely happens, and when it does, the process is long and difficult (Org. G).

Variable Willingness among Employers to Prolong the Careers of Older Finance Professionals

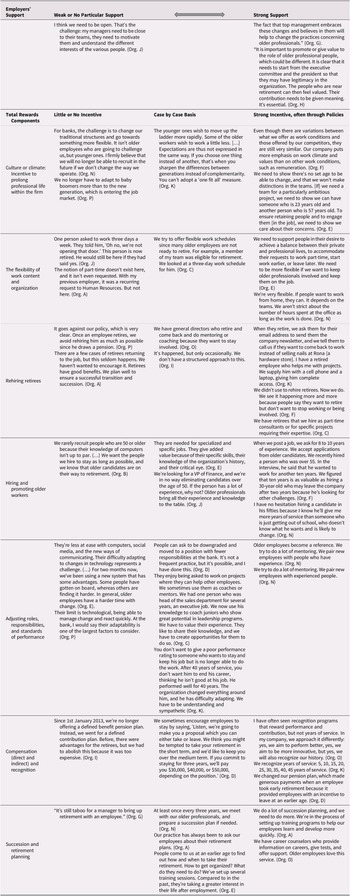

It appears that the organizations in the financial services sector involved in our study varied in terms of the degree to which the organizational culture and values of top management were open to adopting total rewards components encouraging older professionals to prolong their professional lives. Some firms were open to the notion, but others were less so. We can place the study participants’ management actions concerning older professionals on a continuum showing that the total rewards practices concerning older professionals in the financial services sector reflect top management’s support and the organizational climate (see Table 1).

Table 1: Continuum of employers’ practices toward older professionals in the finance sector

At one end of this continuum (left side of the table) are organizations with few or no total rewards practices encouraging older workers to continue working longer; instead, they might even adopt programs that may incite older professionals to leave. In the middle of the continuum, organizations manage their older professionals’ requests mostly on a case-by-case basis, depending on their job position, work context, and individual characteristics (expertise or experience). At the other end (right side of the table) are the most supportive employers applying an inclusive organizational culture who adopt many total rewards practices aimed at older employees and, often, even at their staff as a whole.

Many of these supportive employers emphasized the importance of an inclusive culture for all employees, including women, but especially for young people. Some participants stated that attracting and retaining younger workers represented a more significant challenge and felt uneasy that our study focused on keeping older professionals at work.

“For banks, the challenge is to change our traditional structures and go towards something more flexible. It isn’t older employees who are going to challenge us, but younger ones. I firmly believe that we will no longer be able to recruit in the future if we don’t change the way we operate” (Org. N).

“We no longer have to adapt to baby boomers more than to the new generation, which is entering the job market.” (Org. P).

Total Reward Components Prevalence According to the Level of Executive Support

As illustrated in Table 1, the participants adopted various total reward components to encourage older workers to continue working for their employers. However, the actual prevalence of each of these practices within these firms varied according to the level of executive support behind them and the firms’ respective organizational culture or climate; that is, was the culture or climate more or less open to retaining older professionals. We attribute the extremes of the continuum to some rewards components based on a frequency order. These include flexibility in working time and place of work; rehiring retirees; hiring and promoting older workers; adjusting roles, responsibilities, and standards of performance; monetary rewards and benefits; and, finally, succession and retirement planning or preparation.

Flexibility in working time and workplace

Most respondents stated that they used or should have relied more on a flexible work schedule to retain older employees. According to them, a part-time schedule accommodates or responds to older professionals’ expectations by facilitating their retirement transition. Our respondents mentioned that the phased or gradual retirement of older workers might also facilitate knowledge transfer. As one participant said,

“We need to support people in their desire to achieve a balance between their private and professional lives, to accommodate their requests to work part-time, start work earlier, or leave later. We need to be more flexible if we want to keep older professionals involved and keep them on the job” (Org. E).

Some respondents said that offering flexibility to all employees is part of the collective agreement: “According to our collective agreement, employees can ask to work three days a week. We do everything possible to make this happen” (Org. H). However, in most cases, it was justified because it answers the needs of all employees: “There aren’t more requests to work part-time among employees who are 55 and older or fewer among 30-year-olds. There’s no difference” (Org. F). Similarly, two other participants said that working from home was possible for all employees if their job allowed it.

“We’re very flexible. If people want to work from home, they can. It depends on the teams. We aren’t strict about the number of hours spent at the office as long as the work is done. We have to remain flexible. Everyone wants to balance the different spheres of their lives. Even older employees want this now” (Org. N).

However, three employers stated that they did not offer the possibility to work part-time, either because older employees did not request it or because top management was not in favor of it. As expressed by a participant: “The notion of part-time doesn’t exist here, and it isn’t even requested. With my previous employer, it was a recurring request to Human Resources. But not here” (Org. A). Another participant recognized that this refusal by top management triggered retirements. “One person asked to work three days a week. They told him, ‘Oh no, we’re not opening that door.’ This person is now retired. He would still be here if they had said yes” (Org. J).

Rehiring retirees

Half of the study participants mentioned the importance of rehiring retirees. Some said that their top management encouraged retiree hiring, mainly to provide support during busy periods, fill occasional needs requiring expertise, or replace workers during vacations and days off. One participant stated:

“When they retire, we ask them for their email address to send them the company newsletter, and we tell them to call us if they want to come back to work instead of selling nails at Rona [a hardware store]. I have a retired employee who helps me with projects. We supply him with a cell phone and a laptop, giving him complete access” (Org. K).

However, three participants stated that they rarely rehired retirees because top management does not support it for various reasons. For example, their organization might prefer to focus on up-and-coming employees and effective succession planning. In one firm, a participant said that younger employees were waiting for older employees to leave to obtain a promotion. Rehiring retirees might also be against company policy or perceived as unjust or unfair by employees: “There are a few cases of retirees returning to the job, but this seldom happens. We haven’t wanted to encourage it. Retirees have good benefits. We plan well to ensure a successful transition and succession” (Org. A). Another respondent stated, “It goes against our policy, which is very clear. Once an employee retires, we avoid rehiring him as much as possible since he draws a pension” (Org. P).

Hiring or promoting older workers

Five participants said that they hired older professionals because of their value-added experience. One participant declared, “We’re looking for a VP of Finance, and we’re in no way eliminating candidates over the age of 50. If the person has a lot of experience, why not? Older professionals bring all their experience and knowledge to the table” (Org. J). Some participants perceived older candidates as more stable, committed, and loyal than younger workers who might be more apt to leave the organization.

Similarly, one participant reported considering older candidates, particularly when deciding whom to promote, to keep these workers committed and give them career opportunities.

“When we post a job, we ask for 8 to 10 years of experience. We accept applications from older candidates. We recently hired a person who was over 55. In the interview, he said that he wanted to work for another ten years. We figured that ten years is as valuable as hiring a 30-year-old who may leave the company after two years because he’s looking for other challenges” (Org. F).

However, one respondent stated that his company rarely hired older professionals because of their lack of technological skills. When it happened, it was limited to positions requiring interpersonal or marketable skills. In his words, “We rarely recruit people who are 50 or older because their knowledge of computers isn’t up to par. We recruit candidates who are 50 or older for jobs where they are on the road, such as in business development activities” (Org. B).

Adjusting roles, responsibilities, and performance standards

Six participants said that they encouraged older professionals to act as mentors or coaches to make the most of their experience and expertise and transfer their knowledge to younger employees. As one respondent stated, “We try to do a lot of mentoring. We pair new employees with experienced people” (Org. N). According to these respondents, older workers were happy to share their knowledge with younger workers. This adjustment in their role at work reduced the feeling that their career had plateaued, bringing new life to their job and keeping them motivated while enabling their organization to retain the wealth of experience they had. According to one participant,

“They enjoy being asked to work on projects where they can help other employees. We sometimes use them as coaches or mentors. We had one person who was head of the sales department for several years, an executive job. We now use his knowledge to coach juniors who show great potential in leadership programs. We have to value their experience. They like to share their knowledge, and we have to create opportunities for them to do so” (Org. C).

Two participants admitted that they might reduce older professionals’ responsibilities and go so far as to downgrade them. “People can ask to be downgraded and moved to a position with fewer responsibilities at the bank. It’s not a frequent practice, but it’s possible, and I have done this” (Org. D). In contrast, one respondent felt that an employer should be more lenient in assessing older employees’ performance.

“You don’t want to give a poor performance rating to someone who wants to stay and keep his job but is no longer able to do the work. After 40 years of service, you don’t want him to end his career, thinking he isn’t good at his job. He performed well for 40 years. The organization changed everything around him, and he has difficulty adapting. We have to be understanding and sympathetic” (Org. K).

However, some respondents agreed that it was difficult, if not impossible, to adapt jobs that have undergone technological and structural changes to fit older professionals’ skills. One respondent explained,

“Their limit is technological, being able to manage change and react quickly. At the bank, I would say their adaptability is one of the largest factors to consider” (Org. P).

Another stated,

“They have greater difficulty adapting to change. For two months now, we’ve been using a new system that has some advantages. Some people have gotten on board, whereas others are finding it harder. In general, older employees have a harder time with change, adapting to change” (Org. E).

Compensation (direct and indirect) and recognition

Several participants stressed how important it was to ensure that offering reduced hours to older professionals, or even occasionally rehiring them, would not have any negative impact on their compensation or pension plan. Otherwise, such practices would be of no interest to them and would not encourage them to prolong their professional lives: “It’s important for them that their pension is not reduced if they adopt a 4-day workweek” (Org. K). Some respondents spoke of the importance of awarding older professionals with symbolic and monetary recognition to highlight their years of service or keep them employed longer. One respondent said,

“I have often seen recognition programs that reward performance and contribution, but not years of service. In my company, we approach it differently: yes, we aim to perform better, yes, we aim to be more innovative, but yes, we will also recognize our history” (Org. O).

The participants’ opinions on the links between pension plans and retirement departures were somewhat mixed. One participant said that management had decided to hold onto its defined benefit pension plan because it helped attract and retain talent. However, two other participants stated that their company had changed its defined benefit pension plan to a defined contribution pension plan to reduce the costs and risks and the incentive to quit earlier. “We changed our pension plan, which made generous payments when an employee took early retirement because it provided employees with an incentive to leave at an earlier age” (Org. D). Another respondent said, “Since January 1, 2013, we’re no longer offering a defined benefit pension plan. Instead, we went for a defined contribution plan. Before, there were advantages for the retirees, but we had to abolish this because it was too expensive” (Org. I).

Succession and retirement planning

Three participants spoke of their planning efforts, aimed at allowing for the transfer of knowledge and determining the availability of successors for certain positions:

“Our practice has always been to ask our employees about their retirement plans. We have pretty clear succession plans that cover the whole organization. We generally have a succession plan mapped out and plan retirements to ensure a smooth transition” (Org. A).

Three participants said they offered older employees training sessions or meetings with experts to plan their retirement or sometimes prolong their professional lives. Many employees requested this measure at an earlier age. It often helped them with their transition into retirement.

“We have career counselors who provide information on careers, give tests, and offer support. Older employees love this service” (Org. O).

“People come to us at an earlier age to find out how and when to take their retirement. How to get organized? What do they need to do? We’ve set up several training sessions. Compared to in the past, they’re taking a greater interest in their life after employment” (Org. E).

However, one employer stated that succession planning remained taboo at his firm and appeared to be a source of embarrassment in the relations between supervisors and subordinates: “It’s still taboo for a manager to bring up retirement with an employee. We have worked on this to make it less confrontational. An organization should evaluate the risks of an employee retiring and set up an action plan” (Org. G).

Discussion

In this qualitative study, we interviewed 16 executives from the financial services sector regarding their total rewards practices concerning older professionals. Their opinions were congruent with the black box model of HRM (Boxall & Purcell, Reference Boxall, Purcell, Wilkinson, Gollan, Marchington and Lewin2011) that takes into account the organizational context (e.g., industry, culture, managers’ support) when considering the adoption, interpretation, and impacts of the HRM practices on various objective and perceptual performance indicators. The executives’ openness to the notion of job retention is very variable. Facing many demographic and technological challenges, finance sector executives adopt various actions concerning diversity. They do not necessarily see older professionals as the most important or strategic assets, depending on their culture and HRM strategy. Such a result is congruent with the findings of studies showing that actions designed to raise managers’ awareness of diversity are more effective than those aimed at structural changes such as HRM policies (Cornet & El Abboubi, Reference Cornet and El Abboubi2012; Jin, Lee, & Lee, Reference Jin, Lee and Lee2017). O’Leary and Sandberg (Reference Sandberg2017) also mention the importance of managers understanding the notion of diversity, as this influences the type of practices used. Similarly, to reap the benefits associated with a mature and age-diverse workforce, Parker and Andrei (Reference Parker and Andrei2020) propose that management adopt three meta-strategies: include, individualize, and integrate.

In our study, the most open employers were more likely to adopt inclusive management to include and integrate all employees regardless of their sub-group characteristics (e.g., age, gender, ethnic origin). Mid-way in the continuum, many employers were more likely to manage older employees on a case-by-case basis. At the other extreme, employers still do not see the added value of keeping them at work and are concerned about the potential perceptions of inequality held by other employees if they would offer particular rewards to retain older employees. It also appears that all total reward practices mentioned by respondents are congruent with prior studies and could be related to the four types of practices (e.g., developmental, maintenance, utilization, and accommodative). However, assigning each total reward practice remains ambiguous (Kooij et al., Reference Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers and de Lange2014): one practice (e.g., part-time work) might be classified as utilization or accommodation.

Flexibility in Working Time and Workplace

Some respondents pointed out that if top management genuinely wishes to retain older professionals, they need to adapt working conditions to their needs. Several respondents stated that their firm offers a flexible schedule or even an option to work from home to all their personnel, because new technologies make it possible to work from anywhere. As one of them put it, “We have to allow them to work 3 or 4 days a week so as not to lose them or their knowledge completely. In the future, we need to be open to this type of request” (Org. F). This result is congruent with prior studies showing that these are the most critical practices to encourage older workers to stay at work (Guérin & Saba, Reference Guérin and Saba2003; Tremblay & Genin, Reference Tremblay and Genin2009). Flexible working conditions enable them to leave the job market gradually (Retraite Québec, 2016).

However, other participants said that they did not offer time and workplace flexibility to their older workers because the latter did not ask for it and they themselves were not interested in this arrangement. This type of argument is similar to the discrepancy found in Armstrong-Stassen’s (Reference Armstrong-Stassen2008) study. On the one hand, half of the organizations interviewed did not adopt certain practices because they believed their older workers were not interested in them. On the other hand, more senior employees expressed having no access to these practices because they were not considered a priority by their employer.

Some participants explained the sector’s resistance to telework through the risk of confidentiality loss. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, and probably in the future, most financial institutions professionals have been working and will work mainly or entirely from home. Telework might improve the willingness of older employees to continue to work longer, as it offers various benefits such as less interference at work, work schedule flexibility, cost and time loss reduction (e.g., for travel, lunch), autonomy, and better work-family balance (St-Onge & Lagassé, Reference St-Onge and Lagassé1996; Tremblay & Thomsin, Reference Tremblay and Thomsin2012). However, prior studies have also confirmed that working from home might have many drawbacks, such as longer hours, feelings of isolation, difficulties in communicating and disconnecting from work, work invading personal life, overwork, and increasing computer control. Consequently, telework is not without risks to employees’ well-being and physical health, particularly for older employees, and employers should comply with conditions for success (Haines, St-Onge, & Archambault, Reference Haines, St-Onge and Archambault2002; St-Onge & Lagassé, Reference St-Onge and Lagassé1996; Taskin & Tremblay, Reference Taskin and Tremblay2010).

Rehiring Retirees and Hiring or Promoting Older Workers

Several respondents stated that they hired or promoted older professionals because of their greater expertise, experience, and commitment. Some even stated that older employees might be retained longer than younger recruits, as reported by Duxbury and Halinski (Reference Duxbury and Halinski2014). Some participants said that their company valued rehiring their retirees on an occasional and temporary basis, which is more relevant for older finance professionals who hold valuable expertise and experience. To date, too few studies have investigated the issue of rehiring retirees, although some have shown that retirees are likely to appreciate being rehired to earn additional income (Guérin & Saba, Reference Guérin and Saba2003; Latulippe et al., Reference Latulippe, St-Onge, Gagné, Ballesteros-Leiva and Beauchamp-Legault2017). A report by Retraite Quebec (2016) indicates that offering retirees the opportunity to continue working in their organization following their retirement appears to be a retention factor and an increasingly popular practice. Such a practice is consistent with the theory of continuity, which postulates that older workers who were engaged in their careers may wish to remain engaged during retirement. The opportunity for them to work in a transitional job would be consistent with this value.

Adjusting Roles, Responsibilities, and Performance Standards

Adjusting the roles and responsibilities of older employees was a practice put forward by some respondents. Encouraging older professionals to act as mentors or reducing their duties, for example, can motivate them to continue working longer. To succeed in keeping them employed, as one participant from HR explained, “We have to value the experience they’ve acquired and to respect their need for autonomy and flexibility. Since they enjoy sharing their knowledge, we should create opportunities for them to do so” (Org. C). These practices may be classified as utilization practices (Kooij et al., Reference Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers and de Lange2014) that allow organizations to use older employees’ knowledge and experience.

However, many authors have reported that poor health and physical or psychological limitations precipitate retirement (Bélanger et al., Reference Bélanger, Carrière and Sabourin2016; Bettache, Reference Bettache2007; Lefebvre, Merrigan, & Michaud, Reference Lefebvre, Merrigan and Michaud2011; Pignal, Arrowsmith, & Ness, Reference Pignal, Arrowsmith and Ness2010). A study by Wind et al. (Reference Wind, Geuskens, Ybema, Blatter, Burdorf and Bongers2014) indicates that employees with chronic illnesses may want to leave the job market earlier to enjoy a measure of good health before it deteriorates. In such a case, employers have to offer and accept to accommodate older employees to retain them or to meet legal requirements. In some countries (Canada, France, Great Britain, the United States), recent legislation requires employers to offer a worker or a group reasonable accommodation that does not impose undue hardship. Reasonable accommodation applies to several discrimination motives, including sex, pregnancy, disability, religion, and age. At the root of this legal obligation is the principle that employees (e.g., older employees) do not have to bear the full burden of accommodation in the workplace. In Québec, for example, employers must fulfill their legal obligation to seek reasonable alternatives that enable older employees to remain in their current position through adjustments (e.g., changes in duties, schedules, shift, equipment) and to achieve an acceptable level of productivity.

Compensation and Recognition

The present study results also support the impacts of direct compensation, benefits, and recognition on prolonging older workers’ professional lives. Some participants pointed out that more senior employees who choose to work part time or agree to return to work for a pre-established period should not see their pension conditions negatively affected. Others stated that they paid retention premiums to key older professionals, while others stressed the importance of offering competitive compensation (fixed and variable). However, one HR professional participant stated that organizational culture has a better competitive added value than direct or indirect compensation components to retain older employees. According to him, “Even though there are variations between what we offer as work conditions and those offered by our competitors, they are still very similar. Our company puts more emphasis on work climate and values than on other work conditions, such as compensation.” (Org. F).

Succession and Retirement Planning

Lastly, succession planning was not a practice that was foremost in the minds of the study participants. Its absence appears problematic, because many older professionals in the financial services sector retire with highly specialized experience, knowledge, and expertise, in some instances leaving behind clients who have been loyal to their services and the company for years. One participant expressed this as a challenge: “What worries me is how we are going to be able to transmit the intelligence, behaviors, and ability to adapt of the past 25 years to future generations” (Org. O). Nevertheless, some respondents said that they offered informal support for retirement planning that their older employees appreciated.

The Particularities of the Financial Services Sector

The study participants also observed that significant technological and structural changes in the financial services sector might be influencing employers’ efforts to retain older professionals. Advances in computer science and artificial intelligence bring significant structural challenges affecting the job content in the financial services sector of developed countries (Noonan, Reference Noonan2017; St-Onge, Magnan, & Vincent, 2022). These factors modify the business model of financial institutions, leading to significant reductions among employees who have more technical skills, mainly in regional service centers or outside large urban centers. Many functions previously performed at local or regional service points are now centralized, often at the head office. McKinsey & Company (2020) reports that more than half of current claims activities could be automated by 2030. The technology revolution is reshaping all jobs, eliminating some roles and creating new digital functions, while most positions will have to handle new responsibilities and build new skills.

Added to the pressure to reduce costs given the continued profitability challenge, the COVID-19 pandemic has further accelerated this revolution in the financial services sector. Karpinska et al. (Reference Karpinska, Henkens and Schippers2013) show that organizational circumstances (e.g., labor shortage, need to downsize) influence a firm’s efforts to retain older workers. In this context, employers compete to attract candidates with recent training in predictive analytics, artificial intelligence, programming, and systems maintenance; namely, possessing skills that older workers lack. However, there are departments, such as sales, services, and the follow-up of high priority claims that do require older professionals’ expertise. As one participant put it, “Their strength is their practical experience. They have incredible networks. These are things you don’t learn in school. It’s a huge wealth” (Org. H). The importance of retaining and transferring older professionals’ knowledge, therefore, remains critical. Similarly, interviews with financial sector managers (Kolbjørnsrud, Amico, & Thomas, Reference Kolbjørnsrud, Amico and Thomas2016) have indicated that artificial intelligence is no substitute for the value of human judgment and ethical thinking. In other words, it is going to be crucial to stand out through cross-disciplinary interpersonal skills essential to networking, coaching, creativity, and teamwork.

As Lagacé and Terrion (Reference Lagacé and Terrion2013) demonstrate, the negative effect of new technologies on older workers’ retention could be mitigated by continuing training. Consequently, employers in the financial services sector would benefit enormously from adopting, better communicating, and institutionalizing an inclusive approach to older worker management, going beyond a case-by-case approach to avoid confusion or inequality (real or perceived). We conducted our study before the pandemic crisis, and it appears that our respondents offered few formalized rewards, practices, or policies targeting older professionals other than the firm’s seniority recognition program. Therefore, it is imperative to inform, sensitize, and train executives and managers regarding ageism and to review practices aimed at older workers, given the enormous technological transformations that they face and will have to deal with in the future and their frequent difficulties in following and adapting to them. It is crucial that HR professionals document and communicate any practices and policies to help older workers be motivated to stay longer at work.

Conclusion

Our study expands on the literature addressing older employee management by focusing on the finance sector, which is subject to enormous pressures. In line with the black box model of HRM, the results of this study provide greater insight into how employers in the financial services sector envisage, interpret, and enact the management of older professionals and how this affects the complex psychological and social climate within firms (Boxall & Purcell, Reference Boxall, Purcell, Wilkinson, Gollan, Marchington and Lewin2011). Some organizations in this sector stand out in terms of their top management support of older professionals, which promotes a culture inclusive of them and adopts specific total rewards components to keep them working longer. Given the diversity of management practices concerning older professionals among the organizations in any sector, the black box model needs to be used in future research to understand which reward components work best in which contexts.

This study is not without some limitations. Although our sample included large firms in the Canadian financial services sector, the results cannot be generalized to the whole industry and to other countries. Older employees’ behaviors depend on governmental measures (e.g., mandatory retirement ages, discouraging early retirement) that are not under employers’ control (Tremblay, Reference Tremblay2019). Furthermore, when interviewing the employers regarding their practices concerning older employees, our study minimized the individual factors behind employees’ decisions to retire or leave and find a job elsewhere (e.g., spouse’s health). It is then crucial to adopt a multi-level approach, such as in Bal, de Jong, Jansen, and Bakker’s (Reference Bal, de Jong, Jansen and Bakker2012) study. Moreover, the financial services sector, confronted with enormous and continuous technological changes, may be more susceptible to the presence of ageism or age-related discrimination (Snape & Redman, Reference Snape and Redman2003). This potential stigmatization bias may have affected our results. A desirable positive bias might also have affected our participants’ answers. Posthuma and Campion (Reference Posthuma and Campion2009) have identified many negative stereotypes of older employees in the finance, retail, and information technologies sectors. More than 10 years later, the financial services sector is particularly subject to technological and structural pressures that result in candidates being considered “old” at an earlier age, depending on the positions needing to be filled. However, our results show variance among employers’ total rewards practices offered to their older professionals.

It would also be worth taking an individual perspective. For example, we could investigate whether finance professionals are likely to be considered “old” earlier than professionals in other sectors and whether there is a kind of turnover contagion phenomenon (Felps et al., Reference Felps, Mitchell, Hekman, Lee, Holtom and Harman2009), using the process model of collective turnover. It would also be helpful to study older employees’ rated usage of the available rewards practices. Future studies would benefit from adopting a questionnaire-led approach involving various actors (e.g., older workers, managers, HR professionals, immediate supervisors) to fully explore the black box model. A study on employee turnover in general (Grotto, Hyland, Caputo, & Semedo, Reference Grotto, Hyland, Caputo, Semedo, Goldstein, Pulakos, Passmore and Semedo2017) called for increasing knowledge of where older employees go and what they do after leaving their organization (i.e., whether they retire or join another firm).

It would also be essential to gain better insight into creating a favorable climate that encourages managers to support older employees to a higher degree throughout their work and environment changes. It would be useful to examine how lack of managerial support can push older employees into early retirement (Karpinska et al., Reference Karpinska, Henkens and Schippers2013). Future research might use signal theory (Spence, Reference Spence, Diamond and Rothschild1978) to understand how older workers or job applicants decode the available information on an organization as a signal of its working conditions (Cable & Turban, Reference Cable and Turban2003). Researchers could also investigate whether older workers or external job applicants perceive the age-related total rewards practices adopted and communicated by employers (via various media, including the company Web site) as a positive work climate signal. In this study, we investigated the opportunities for older finance professionals to keep working for an organization. Future studies might instead examine what factors lead them to find another job in the labor market or work for a competitor.

Funding

The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada supported this work under Grant 435-2017-1203.