Background

Dementia is a disease that affects the lives of millions of older adults (65 years and older) both in Canada and across the globe (Prince, Comas-Herrera, Knapp, Guerchet, & Karagiannidou, Reference Prince, Comas-Herrera, Knapp, Guerchet and Karagiannidou2016). Dementia is a clinical syndrome of deterioration in cognition that negatively affects daily functioning, and it is not an outcome of delirium or another condition (i.e., medical, neurological, or psychiatric) (Chertkow, Feldman, Jacova, & Massoud, Reference Chertkow, Feldman, Jacova and Massoud2013). The most common causes of dementia include Alzheimer’s disease (50–75%), followed by vascular dementia (20–30%), frontotemporal dementia (5–10%), and dementia with Lewy bodies (< 5%) (Prince, Albanese, Guerchet, & Prina, Reference Prince, Albanese, Guerchet and Prina2014). As a result of the aging population, it is expected that the number of Canadians living with dementia will reach 937,000 by 2031 (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2016). Further, diagnosing dementia can be a complex and complicated process, and due to the high rates of undiagnosed cases, this is likely an underestimate of true prevalence (Bradford, Kunik, Schulz, Williams, & Singh, Reference Bradford, Kunik, Schulz, Williams and Singh2009).

In Canada and beyond, underdiagnoses and misdiagnosis of dementia pose a significant barrier to effective dementia treatment and management (Prince et al., Reference Prince, Comas-Herrera, Knapp, Guerchet and Karagiannidou2016). At the same time, there is a large body of research that emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis and treatment in improving the quality of life and health outcomes among those living with dementia (Barth, Nickel, & Kolominsky-Rabas, Reference Barth, Nickel and Kolominsky-Rabas2018; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Kosteniuk, Stewart, O’Connell, Kirk, Crossley and Innes2015; Prince et al., Reference Prince, Comas-Herrera, Knapp, Guerchet and Karagiannidou2016). Applying a team-based care approach to managing chronic conditions, including dementia, has been recommended as efficient, cost-effective, and patient-centred (Chamberlain-Salaun, Mills, & Usher, Reference Chamberlain-Salaun, Mills and Usher2013; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Kosteniuk, Stewart, O’Connell, Kirk, Crossley and Innes2015). Ideally, with adequate training and support, a primary health care (PHC) team can effectively diagnose and manage dementia among their patients (Massoud, Lysy, & Bergman, Reference Massoud, Lysy and Bergman2010).

In Canada, PHC refers to primary prevention, public health, and health care services supplied by a range of providers in a variety of settings, in a way that is person- and population-centred (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2014). Collaborative PHC teams are typically led by a family physician and consist of health care professionals from varying disciplines (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, McMillan, Kachan, Paradis, Leslie and Kitto2015); this type of approach is often referred to as interprofessional team-based care. Another term to describe this type of collaboration is interdisciplinary. Both interprofessional and interdisciplinary indicate coordinated collaboration among health care professionals from different disciplines. Common elements associated with interprofessional/interdisciplinary team-based care include (a) shared team identity with clear individual roles; (b) collaborative work towards common goals and objectives; (c) strong understanding of other team members’ knowledge, roles, and expertise; (d) shared responsibility and team decision-making processes; and (e) open communication and information-sharing procedures (Mickan & Rodger, Reference Mickan and Rodger2005; Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Goldman, Gilbert, Tepper, Silver, Suter and Zwarenstein2011, Reference Reeves, McMillan, Kachan, Paradis, Leslie and Kitto2015). The type and number of professionals that make up the team may vary largely depending on the availability of services in the area. In the literature, interprofessional and interdisciplinary are often used interchangeably with multiprofessional or multidisciplinary, and these terms all refer to multiple health care professionals caring for the same patient; however, coordinated and ongoing collaboration is lacking among multiprofessional/multidisciplinary disciplines (Chamberlain-Salaun et al., Reference Chamberlain-Salaun, Mills and Usher2013).

In an effort to better understand the factors influencing interprofessional teamwork, Reeves et al. (Reference Reeves, McMillan, Kachan, Paradis, Leslie and Kitto2015) developed a theoretical framework consisting of four domains influencing team-based collaboration: relational, processual, organizational, and contextual. Dahlke et al. (Reference Dahlke, Meherali, Chambers, Freund-Heritage, Steil and Wagg2017) recently applied this framework in their scoping review aimed at understanding how interprofessional teams are able to improve health outcomes of older adults experiencing cognitive challenges. Results of this study indicated that (a) collaboration among staff, (b) communication mechanisms, and (c) education interventions were most effective in supporting interprofessional collaborations that resulted in positive outcomes for care teams and patients. Their research highlighted the value of applying a team-based approach when caring for older adults with cognitive challenges. However, the authors also identified the need for further research aimed at describing the processes that teams use to collaborate. Moreover, as indicated in the framework created by Reeves et al. (Reference Reeves, Goldman, Gilbert, Tepper, Silver, Suter and Zwarenstein2011), it is also important to understand how broader contextual and environmental factors (e.g., geographic locale, availability of health care professionals, policies, and access to resources) may impact the processes employed by teams.

For instance, geographic setting (i.e., rural versus urban) can have a significant impact on the availability of health care professionals and resources which, in turn, impacts the ability of a PHC team to work collaboratively (Dandy & Bollman, Reference Dandy and Bollman2008; Ford, Reference Ford2016; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Kosteniuk, Stewart, O’Connell, Kirk, Crossley and Innes2015). In Canada, adults aged 65 years and older account for approximately 20 per cent of the rural population, compared to approximately 16 per cent of the urban population (Statistics Canada, 2016). In addition, evidence suggests there is a higher incidence and prevalence of dementia in rural areas (Russ, Batty, Hearnshaw, Fenton, & Starr, Reference Russ, Batty, Hearnshaw, Fenton and Starr2012). In the literature, a variety of definitions are applied to define and describe rurality. Given the variation in rural environments, researchers have advised against applying one single definition to describe rural; rather, it is suggested that authors provide a detailed description of how the term rural is operationalized within their study (Keating, Swindle, & Fletcher, Reference Keating, Swindle and Fletcher2011; Moazzami, Reference Moazzami2015). Generally, there are common features identified among all rural and remote settings: unique social patterns, a widely dispersed population, an economy that is often agriculturally based, and with limited access to health care resources including dementia-specific primary health care services (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Kosteniuk, Stewart, O’Connell, Kirk, Crossley and Innes2015; Prince et al., Reference Prince, Comas-Herrera, Knapp, Guerchet and Karagiannidou2016). Such information is necessary for understanding the implications and generalizability of study findings to other rural settings outside of the target population. Limited access to health care resources is particularly concerning when considering the role of PHC teams in dementia care (Prince et al., Reference Prince, Comas-Herrera, Knapp, Guerchet and Karagiannidou2016). Moreover, research reveals numerous challenges associated with access to dementia care in rural areas (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Kosteniuk, Stewart, O’Connell, Kirk, Crossley and Innes2015), with little information about evidence-based best practices to guide team-based care for rural residents living with dementia (Innes, Morgan, & Kostineuk, Reference Innes, Morgan and Kostineuk2011; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Kosteniuk, Stewart, O’Connell, Kirk, Crossley and Innes2015).

Collaborative team-based PHC has been identified as a best-practice approach to delivering dementia care (Aminzadeh, Molnar, Dalziel, & Ayotte, Reference Aminzadeh, Molnar, Dalziel and Ayotte2012; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Kosteniuk, Stewart, O’Connell, Kirk, Crossley and Innes2015). However, limited information exists about how PHC teams collaborate to deliver dementia care specifically to individuals living in rural areas with limited resources. Consequently, the aim of our study was to conduct a scoping review of the literature to determine how PHC teams collaborate to deliver comprehensive and integrated dementia care to older adults residing in rural and remote areas. In addition, this study was part of a larger research project in collaboration with the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA). The CCNA, which includes a Women, Gender, Sex and Dementia cross-cutting program (WGSD), is working to increase knowledge and understanding about the underlying genetic, physiological, and social differences between females and males and how these sex and gender differences contribute to the pathology of dementia and delivery of care for persons with dementia (Tierney, Curtis, Chertkow, & Rylett, Reference Tierney, Curtis, Chertkow and Rylett2017). Accordingly, a secondary objective of this scoping review was to examine sex and gender differences in relation to needs and care approaches for patients and families, and, in turn, to examine how PHC teams function to deliver care for rural and remote residents living with dementia.

Methods

The overall review process followed Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) scoping review framework, with additional guidance from Levac, Colquhuon, and O’Brien (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien2010). The guiding framework includes the following five stages: (a) identifying the research aim and question; (b) identifying the relevant research studies; (c) study selection; (d) charting the data; and (e) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

Identifying the Research Questions

As suggested by Levac et al. (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien2010), we gave careful consideration to the population of interest, concepts, and health-related outcomes. Health care professionals caring for rural residents living with dementia and persons with dementia living in rural areas were identified as the target population. The primary outcome of interest was to understand how PHC teams engage in collaborative approaches to deliver dementia care to rural residents. Our secondary goal for this scoping review was to examine sex and gender differences in relation to needs and care approaches for patients and families and, subsequently, to learn how PHC teams function to deliver care for rural and remote residents living with dementia. In an effort to gain detailed information about the processes involved in team-based collaboration, the research team (AFC, DM, MB, JD, VE) identified two specific research questions:

(1) Do primary health care teams describe the team type (e.g., interprofessional, multiprofessional, interdisciplinary), and if so, what are the team compositions?

(2) What are the factors (facilitators and barriers) that have been identified as influencing the implementation of collaborative team-based primary health care approaches for dementia in rural and remote areas?

Identifying Relevant Studies

The comprehensive search strategy we pursued was devised and reviewed by the University of Saskatchewan’s Health Sciences librarian. The strategy focused on four main topics: team type, dementia, primary health care, and rural/remote location. The search was conducted in four electronic databases (Embase, Medline, PsycINFO, and CINAHL). We searched the databases from March 1, 2017, to May 1, 2017. The search was limited to empirical research studies published in peer-reviewed journals; we excluded letters to the editor, opinion letters, commentaries, dissertations, reviews, policy papers, reports, grey literature, and book chapters. To be included, studies had to focus on team-based primary health care delivered by providers from multiple disciplines. Additionally, papers were considered eligible if they presented data on diagnosis and treatment of dementia (all types) and if at least 80 per cent of the participants were aged 65 years and older. Further, articles needed to include study participants who resided in rural and remote areas; however, studies which encompassed participants from urban settings were included if rural-urban comparisons were made. Given the wide variation in definitions applied to describe rural, we accepted studies containing any description of rural. Upon an initial database search, we identified no relevant studies prior to the past 20 years; thus, the search included studies published between 1997 and 2017. An example of our search strategy, including keywords used, can be found in Table 1.

Table 1: Search terms

Study Selection

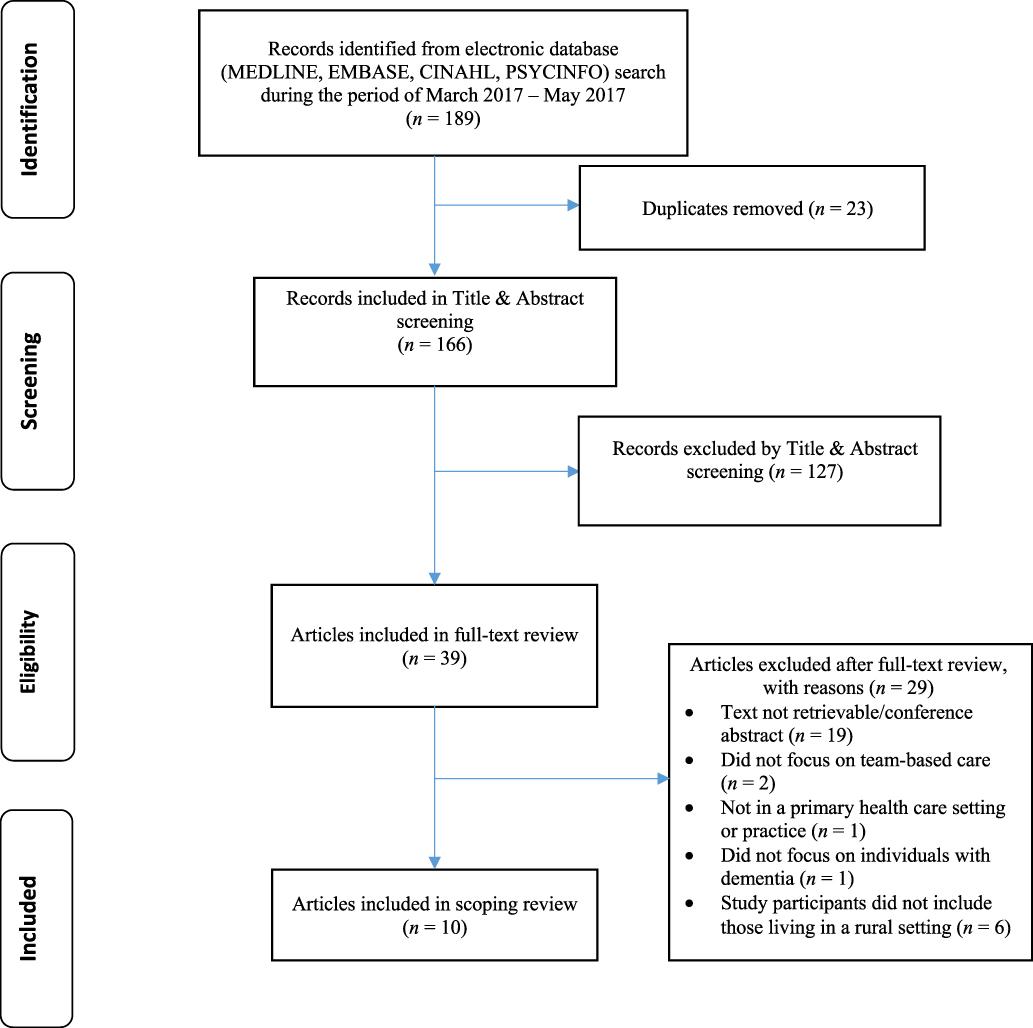

The search resulted in 189 studies which we uploaded to software (EndNote). Once duplicates were identified (via EndNote) and removed, 166 studies remained and were included in title and abstract screening. The included articles were then exported to an electronic systematic review program (DistillerSR). Two reviewers (AFC, MB) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all articles. The full texts from all potentially eligible studies were then reviewed by these same two reviewers using a screening form developed by the first author (AFC). All studies (10) which met the inclusion criteria during the full-text review were included in the scoping study (Figure 1). During the entire review process, a third reviewer was identified to act as an adjudicator (DM) in the event that the first two reviewers could not come to agreement; however, this issue did not arise.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow chart

Charting the Data

The first author developed a customized data charting table in Excel which we used to guide data extraction. Developing the data charting table was an iterative process; consequently, the table was revised on the basis of feedback from research team members to ensure that key data were captured. The final table contained information pertaining to study characteristics that included author, title, and year; study purpose; methods, participants (age and proportion of males versus females), and settings (including identifying those residing in rural and/or remote areas); and findings relevant to the aim of the scoping review (Table 2).

Table 2: Study characteristics and relevant findings

Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting

We collated the data to determine study locations (countries), geographic settings (rural/remote and urban), and the types of studies included. As a team, we engaged in several meetings to discuss how we could use the extracted data to address the scoping review’s goals of understanding how primary health care teams collaborate to deliver comprehensive and integrated dementia care to older adults residing in rural and remote areas. We analysed data to assess how PHC teams defined themselves and determine team compositions. In addition, we reported factors (facilitators and barriers) that were identified as key elements influencing collaboration among PHC teams working to diagnose and care for rural and remote residents living with dementia.

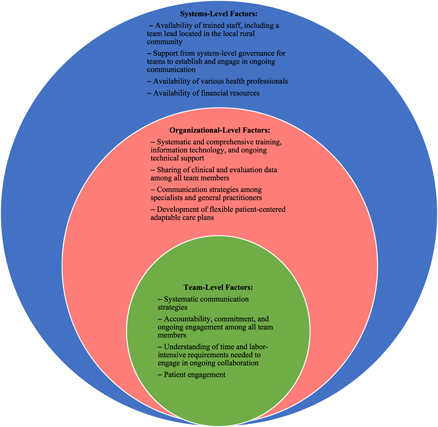

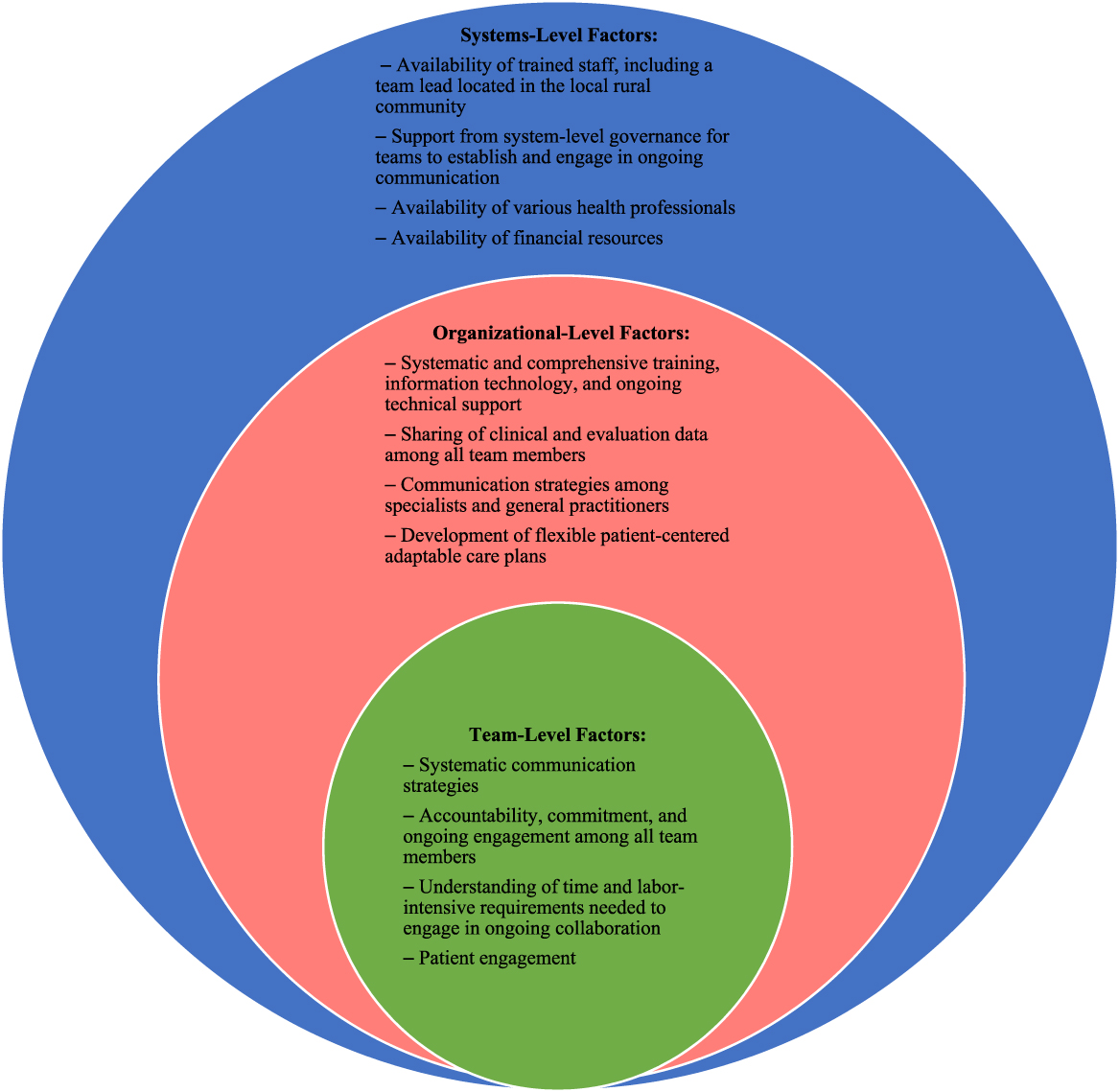

An adapted version of the socio-ecological model (Figure 2) was the framework we employed to report factors identified as influencing team-based collaborations (McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, Reference McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler and Glanz1988; Misfeldt, Suter, Oelke, & Hepp, Reference Misfeldt, Suter, Oelke and Hepp2017; Mulvale, Danner, & Pasic, Reference Mulvale, Danner and Pasic2008). This framework highlights specific factors that influence behaviours on the assumption that ecological categories are systematically connected. Applying the socio-ecological model has most commonly been used to identify and understand how interrelated factors at multiple levels affect health-related behaviours. Few studies have employed this model when exploring how PHC teams collaborate, particularly in relation to the delivery of dementia care in rural settings. We employed an adapted version of the socio-ecological model which had been applied in previous research aimed at understanding key factors that influence the interactions among interprofessional PHC teams (Misfeldt et al., Reference Misfeldt, Suter, Oelke and Hepp2017; Mulvale et al., Reference Mulvale, Danner and Pasic2008).

Figure 2: Adapted socio-ecological model depicting factors influencing team-based PHC

At the centre of the adapted version of the socio-ecological model are primary care teams (i.e., team level), which employ a collaborative team-based approach to delivering primary health care. Examples of factors at the team level include (a) team dynamics, (b) division of roles within teams, (c) team leadership, (d) communication strategies, and (e) interaction with patients (Goldman, Meuser, Rogers, Lawrie, & Reeves, Reference Goldman, Meuser, Rogers, Lawrie and Reeves2010; Misfeldt et al., Reference Misfeldt, Suter, Oelke and Hepp2017; Mulvale et al., Reference Mulvale, Danner and Pasic2008). The second level (organizational) focuses on factors such as team culture, team vision and goal, training and education, and interactions with health professionals outside of the primary care team (Misfeldt et al., Reference Misfeldt, Suter, Oelke and Hepp2017; Goldman et al., Reference Goldman, Meuser, Rogers, Lawrie and Reeves2010). Lastly, the outermost level (systems) considers factors within the broader context such as socioeconomic and political influences. This would include resource availability (human and financial), space, infrastructure, and existing polices. We used the adapted socio-ecological model in our study to guide the reporting of key themes identified in relation to team-based approaches for diagnosing and treating dementia among rural and remote residents.

Results

The 10 studies we included span four different countries: Canada (5); United States (3); United Kingdom (1); and Norway (1). Of the five Canadian articles, four reported on the same group of primary care memory clinics within the province of Ontario (Lee, Hillier, Heckman, et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Lee, Hillier, Molnar, & Borrie, Reference Lee, Hillier, Molnar and Borrie2017; Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Rojas-Fernandez, Patel, & Lee, Reference Rojas-Fernandez, Patel and Lee2014). The majority (8) of the articles focused on the impact of implementing team-based approaches for dementia diagnosis and treatment to support individuals living in their home or in residential care. The remaining two articles discussed the feasibility of implementing a primary care approach and on how specialist and general practitioners may or may not work together. Among all included studies, a portion of the participants resided in a rural area. However, few details were provided about the rural settings, with only one study providing a definition of rural (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009).

The broad goal of this scoping review was to understand how PHC teams collaborate to care for rural and remote residents living with dementia. Overall, eight studies provided some detail on practices that teams engage in when diagnosing and treating dementia among rural residents (Barton, Morris, Rothlind, & Yaffe, Reference Barton, Morris, Rothlind and Yaffe2011; Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra, & Haugen, Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Robinson, Bamford, Waugh, Fox, Livingston and Katona2014; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Molnar and Borrie2017; Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009; Powers, Homer, Morone, Edmonds, & Rossi, Reference Powers, Homer, Morone, Edmonds and Rossi2017; Rojas-Fernandez et al., Reference Rojas-Fernandez, Patel and Lee2014). However, of these eight studies only four included primary health care teams that were located in local rural communities (Engedal et al., Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Robinson, Bamford, Waugh, Fox, Livingston and Katona2014; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Molnar and Borrie2017; Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014).

The secondary goal of this study was to understand how sex and gender was considered in team-based collaboration and delivery of care; unfortunately, the included studies lacked sufficient information to explore sex and gender, with only two studies reporting the sex of patients (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Morris, Rothlind and Yaffe2011; Powers et al., Reference Powers, Homer, Morone, Edmonds and Rossi2017).

The following section addresses results from the scoping review’s specific research questions: (a) how do the PHC teams describe themselves; and (b) what factors (facilitators and barriers) are identified which are perceived as promoting or hindering the implementation of collaborative team-based primary health care for those living with dementia in rural and remote areas.

Primary Health Care Teams

Six studies explained that teams engaged in interdisciplinary/interprofessional collaboration to diagnose and, in some cases, deliver treatment to rural residents with dementia (Lee, Hillier, Heckman, et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Molnar and Borrie2017; Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009; Powers et al., Reference Powers, Homer, Morone, Edmonds and Rossi2017; Rojas-Fernandez et al., Reference Rojas-Fernandez, Patel and Lee2014). Two articles discussed the involvement of memory clinics led by multidisciplinary teams (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Morris, Rothlind and Yaffe2011; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Robinson, Bamford, Waugh, Fox, Livingston and Katona2014). The remaining two articles did not identify the type of team; rather, authors referred to collaboration among team members in terms of “shared care” and a “PHC team collaboration” (Engedal et al., Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013; Iliffe, Wilcock, & Haworth, Reference Iliffe, Wilcock and Haworth2006).

The number and type of health care professionals composing the teams varied among studies, with the number of professions per team as few as three (nurse, family doctor, and occupational therapist) and as many as 12 (nurse, nurse practitioner, pharmacist, social worker, family therapist, dietitian, physician assistant, occupational therapist, part-time respiratory therapist, chiropractor, chiropodist, and health educator). The teams tended to be larger if the team focused on both diagnosis and treatment of dementia (as compared to diagnosis only). Additionally, the composition of PHC teams was apparently influenced by team location (rural vs. urban communities). Teams located in rural communities tended to include fewer professions. A description of team compositions and geographic location of the teams can be found in Table 3.

Table 3: Primary health care team description and location

Key Factors Necessary for Collaborative Team-Based Care

A variety of facilitators and barriers were identified as impacting (supporting and hindering) the implementation of collaborative approaches to team-based care for individuals with dementia living rural and remote areas. As we have already discussed, the socioecological model provided a framework for understanding these factors at various levels (team level, organizational level, and systems level). A summary of key factors can be found in Figure 2.

Team-Level Factors

All articles (n =10) reported on the importance of ongoing communication among team members (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Morris, Rothlind and Yaffe2011; Engedal et al., Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Robinson, Bamford, Waugh, Fox, Livingston and Katona2014; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Wilcock and Haworth2006; Lee, Hillier, Heckman, et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Molnar and Borrie2017; Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009; Powers et al., Reference Powers, Homer, Morone, Edmonds and Rossi2017; Rojas-Fernandez et al., Reference Rojas-Fernandez, Patel and Lee2014). Authors reported that the development of regular communication and follow-up procedures among team members to discuss all patients attending the clinic was a key component of developing effective and systematic communication strategies (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009; Rojas-Fernandez et al., Reference Rojas-Fernandez, Patel and Lee2014). The communication and follow-up pertained both to situations when team members were co-located, and when team members were divided by geographic locale. Some teams implemented bi-weekly meetings (Powers et al., Reference Powers, Homer, Morone, Edmonds and Rossi2017) or follow-up meetings with all team members on the same day as the patient assessment (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009).

Four of the 10 studies reported on commitment among health professionals as a key element of implementing collaborative team-based approaches (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Morris, Rothlind and Yaffe2011; Engedal et al., Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Robinson, Bamford, Waugh, Fox, Livingston and Katona2014; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Wilcock and Haworth2006; Lee, Hillier, Heckman, et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Molnar and Borrie2017; Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009; Powers et al., Reference Powers, Homer, Morone, Edmonds and Rossi2017; Rojas-Fernandez et al., Reference Rojas-Fernandez, Patel and Lee2014). Directly related to this was the need for all team members to be accountable for their actions and to fulfill their assigned duties; this in turn enhanced role clarity. Lack of continued engagement among team members was identified as a barrier hindering interprofessional collaborations and thus limiting the success of the team-based primary care model (Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014). Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014) found that, during initial diagnosis and treatment, most team members were engaged and willing to work with other health professionals; however, as time went on it was difficult to engage team members in ongoing communication and treatment activities. This may be due in part to the fact that health care professionals had limited understanding and training about the time and labor-intensive commitments of providing dementia care in a team-based clinic model.

Another element associated with ongoing support was the need for team members to take on leadership roles and to step up as champions within the care team. For example, Lee, Hillier, and Weston (Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014) reported that physician champions were a key element to ensuring the successful development and implementation of their interprofessional memory clinics. Lastly, two of the studies discussed the need for health professionals to have confidence in their abilities to diagnose and treat individuals with dementia. This element seemed to be particularly important when teams were not co-located (i.e., health care staff were required to travel between clinics in a number of surrounding rural communities) (Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Wilcock and Haworth2006; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009). For example, some clinicians in local rural clinics were reluctant to test and adapt their skills and to engage in new procedures associated with implementing the team-based approach to dementia care (Engedal et al., Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013).

The ability of teams to engage and interact with patients was indicated in five studies as playing a key role in implementing the team-based approach to dementia care (Lee, Hillier, Heckman, et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Molnar and Borrie2017; Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009; Rojas-Fernandez et al., Reference Rojas-Fernandez, Patel and Lee2014). Ability to engage with patients was closely linked to reluctance of patients to attend the clinic or to complete assessments while at the clinic. Specifically, this was identified as a barrier that teams faced when attempting to engage in ongoing implementation and communication with patients. Reluctance to engage often co-occurred with patients’ reservations in bringing a family member to clinic visits (Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014). This reluctance, in turn, often hindered patient engagement because many patients had cognitive challenges and needed assistance in understanding the requests and instructions from the health care professionals. An additional factor impacting the teams’ ability to engage patients was the lack of flexibility in developing person-centred adaptable care plans. Such plans are important for effective patient engagement and should include processes which respect patients’ preferences, aim to educate the person with dementia and their caregivers, and provide necessary physical and emotional support (The Picker Institute, 2013). Tailoring the care plans for patients was shown to be essential in ensuring that the unique needs of patients with dementia living in rural areas could be addressed (Engedal et al., Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Robinson, Bamford, Waugh, Fox, Livingston and Katona2014; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009).

Organizational-Level Factors

Access to systematic and comprehensive training for team members was identified as a key element in nine of the included studies (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Morris, Rothlind and Yaffe2011; Engedal et al., Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Robinson, Bamford, Waugh, Fox, Livingston and Katona2014; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Wilcock and Haworth2006; Lee, Hillier, Heckman, et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Molnar and Borrie2017; Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009; Rojas-Fernandez et al., Reference Rojas-Fernandez, Patel and Lee2014). Insufficient training among some primary health care team members made it difficult for the team to work closely and engage in interdisciplinary processes. This was particularly true for professionals who were accustomed to working on their own and had not previously collaborated with other professionals (Rojas-Fernandez et al., Reference Rojas-Fernandez, Patel and Lee2014). Authors from three studies suggested that important features of the training included offering in-person sessions on multiple occasions. In addition, standardization of documentation and program delivery was important to ensuring that all team members received the same quality of training (Engedal et al., Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Robinson, Bamford, Waugh, Fox, Livingston and Katona2014; Rojas-Fernandez et al., Reference Rojas-Fernandez, Patel and Lee2014).

Access to information technology and ongoing support for these tools was another important organizational factor influencing team-based collaboration; this was particularly true for telehealth clinics (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Morris, Rothlind and Yaffe2011; Engedal et al., Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013). Having access to a reliable internet connection, for example, is necessary for delivery of the telehealth videoconferencing system. However, some rural and remote regions had limited access to internet and the corresponding technological support needed for the telehealth technology. As a result, this could impede communication between team members who were not co-located, thus hindering interprofessional collaboration among teams and, in turn, delivery of care for persons with dementia (Powers et al., Reference Powers, Homer, Morone, Edmonds and Rossi2017). Additionally, two studies stated that clinical and evaluation data should be shared and available (ideally electronically) to all care team members, even when teams were not co-located (Engedal et al., Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009).

Access to information was also associated with facilitating another key element, which was communication among specialist teams and the referring family physician in the local community. Six studies noted the importance of implementing communication strategies between the specialist dementia care team members located in the urban centre and the local community-based health care practitioners (e.g., social worker, referring doctor, nurse practitioner) located in the patient’s rural community (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Morris, Rothlind and Yaffe2011; Engedal et al., Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Molnar and Borrie2017; Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009; Rojas-Fernandez et al., Reference Rojas-Fernandez, Patel and Lee2014). Such strategies were imperative for ensuring continuity in care between a specialist’s recommendations and PHC practices. In some cases, resistance among primary care physicians in rural clinics to engage with care teams located in a larger urban community was a barrier that hindered ongoing interprofessional collaborations (Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Wilcock and Haworth2006; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009). Lack of communication between the specialist team and the local physician also made it difficult to implement patient-focused care plans.

Systems-Level Factors

All articles noted that the availability of trained staff was essential to the success of implementing interprofessional team-based care models (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Morris, Rothlind and Yaffe2011; Engedal et al., Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Robinson, Bamford, Waugh, Fox, Livingston and Katona2014; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Wilcock and Haworth2006; Lee, Hillier, Heckman, et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Molnar and Borrie2017; Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009; Powers et al., Reference Powers, Homer, Morone, Edmonds and Rossi2017; Rojas-Fernandez et al., Reference Rojas-Fernandez, Patel and Lee2014;). In models where there was collaboration between an urban-based care team and rural health care professionals, a dedicated and trained family physician or nurse practitioner acting as team lead was shown to be an asset in the local rural clinic. Another factor associated with staff availability was the turnover of team members. This was particularly challenging if mechanisms and resources were not available to ensure that incoming staff received the required training (Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014).

Support from system-level governance for team members to have dedicated time to establish and engage in ongoing communication processes was important. Lack of time and support for health care staff to engage in ongoing collaboration and planning as a team was noted as a barrier in three of the included studies (Engedal et al., Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Wilcock and Haworth2006; Powers et al., Reference Powers, Homer, Morone, Edmonds and Rossi2017). Adding to this challenge was the fact that rural communities often had access to fewer disciplines, and thus team members were required to take on a number of additional duties. In turn, this limited the time staff could devote to ongoing collaborations with the team.

We identified the availability of financial resources to support ongoing implementation of team-based approaches as a necessary element contributing to both human resources and infrastructure (space for teams to work collaboratively and, in some cases, assess patients) in all of the studies (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Morris, Rothlind and Yaffe2011; Engedal et al., Reference Engedal, Gausdal, Gjøra and Haugen2013; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Robinson, Bamford, Waugh, Fox, Livingston and Katona2014; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Wilcock and Haworth2006; Lee, Hillier, Heckman, et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Molnar and Borrie2017; Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009; Powers et al., Reference Powers, Homer, Morone, Edmonds and Rossi2017; Rojas-Fernandez et al., Reference Rojas-Fernandez, Patel and Lee2014). Thus, if funds were not available, the teams could not always hire the necessary staff to support the implementation of the collaborative team-based care model. Moreover, when infrastructure was limited, financial resources were required to expand or upgrade spaces to accommodate teams.

Discussion

In this study we aimed to understand how PHC teams collaborate to deliver comprehensive and integrated dementia care in rural and remote areas. In a previous scoping review, Dahlke et al. (Reference Dahlke, Meherali, Chambers, Freund-Heritage, Steil and Wagg2017) investigated how interprofessional teams collaborated to care for older adults with cognitive challenges; however, they did not focus on delivering team-based care in rural and remote areas. Given the unique contextual factors associated with living in rural settings and the fact that many older adults reside in those areas (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Kosteniuk, Stewart, O’Connell, Kirk, Crossley and Innes2015; Prince et al., Reference Prince, Comas-Herrera, Knapp, Guerchet and Karagiannidou2016), our scoping review has addressed an important area of research. Overall, the 10 articles we examined provided information on both types of PHC teams with variation in team composition. In addition, we sought to explore factors influencing how PHC providers engage in team-based collaboration when caring for rural residents living with dementia. A secondary goal of the current study was to examine sex and gender differences in relation to needs and care approaches for patients and families, and also to study how PHC teams function to deliver care to rural and remote areas for residents living with dementia; however, due to the limited information pertaining to sex and gender in the 10 studies identified, we were unable to address this question in our scoping review.

Understanding the context and environment associated with rural and remote settings was pertinent to addressing the primary aim of this scoping review. All studies included participants from rural and remote areas, but only one study in our review provided a definition describing the rural setting (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009). Given the unique contextual factors associated with living in rural and remote communities, it is important that readers understand how rural is defined within each study. Further, because there is no universally agreed-upon definition of rural, it was difficult to determine the degree of rurality (e.g., how distant the communities were from an urban centre) and the differing contextual and environmental factors impacting the implementation of team-based care approaches in each study.

Another issue associated with the broader aim of understanding how PHC teams collaborate was that few studies implemented team-based approaches via a local PHC team working in the same community as did the rural residents. In a number of the studies, the collaborative team-based approach included a specialist team located in an urban setting. Although the expertise of these specialists is important, research suggests that in low-resource settings (such as rural areas), primary health care should play a key role in delivering care to those living with dementia (Prince et al., Reference Prince, Comas-Herrera, Knapp, Guerchet and Karagiannidou2016). Thus, rather than referring all individuals who report dementia symptoms to specialist teams, capacity should be built for local PHC teams (trained and supported by specialists) to play a leadership role in coordinating the diagnosis and treatment for those living with dementia in rural and remote areas (Aminzadeh et al., Reference Aminzadeh, Molnar, Dalziel and Ayotte2012; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Kosteniuk, Stewart, O’Connell, Kirk, Crossley and Innes2015; Prince et al., Reference Prince, Comas-Herrera, Knapp, Guerchet and Karagiannidou2016; Wakerman, Reference Wakerman2009). For more complex cases, where determining diagnosis and treatment is difficult, the PHC team could then refer the patients to a specialist team (Hum et al., Reference Hum, Cohen, Persaud, Lee, Drummond, Dalziel and Pimlott2014; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009). Four of the five Canadian studies discussed the implementation of PHC teams, and the authors reported successes in building capacity among PHC teams with corresponding increases in patient satisfaction; it should be noted that the four studies reporting successes were based on the same primary care–based memory clinic model (Lee, Hillier, Heckman, et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Molnar and Borrie2017; Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Rojas-Fernandez et al., Reference Rojas-Fernandez, Patel and Lee2014).

In addition to our broad research aim of understanding how PHC teams work collaboratively to care for individuals living with dementia in rural and remote areas, we attempted to address two specific research questions. Our first research question was to determine if and how primary health care teams describe the team-based approach they employed; and to identify the various team compositions. All studies reported working as a particular type of team (interdisciplinary/interprofessional, multidisciplinary, shared care, and primary health care); however, few studies included a specific definition for the type of team employed. Consequently, the corresponding definition with the team type identified did not always match the process by which the teams did or did not collaborate. For example, one study referred to implementing a multidisciplinary team-based approach when in fact their team was working collaboratively with multiple health professionals and could have been more accurately described as an interdisciplinary/interprofessional team (Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Robinson, Bamford, Waugh, Fox, Livingston and Katona2014). This finding supports previous recommendations for the need to establish consistency in terminology used to describe and differentiate how various types of health care teams function (Chamberlain-Salaun et al., Reference Chamberlain-Salaun, Mills and Usher2013). Establishing consensus in terminology and associated definitions will, in turn, provide a better understanding of the division of roles and benefits of interdisciplinary/interprofessional collaborations when caring for those with dementia in primary care settings.

When investigating the various team compositions, we found that most authors identified the health professionals included on their teams; for example, all teams included a specialist or general practitioner and a nurse. Additional team members varied across studies and within studies that had multiple teams. The availability of multiple professions tended to be limited when PHC teams were located in rural communities (i.e., rural-based teams had more limited access to a variety of health care professionals). This finding provides further support for the recommendation that PHC teams in rural communities should be supported in order to provide more comprehensive and integrated dementia care (Boscart, Reference Boscart2016).

Our second research question was to identify factors that teams perceived as influencing the implementation of collaborative team-based approaches when caring for rural residents living with dementia. We employed an adapted version of the socio-ecological model to understand and organize these key factors by team level, organizational level, and systems level. At the team level, the most commonly reported factor was ongoing communication among the care team. This included establishing mechanisms to ensure that teams met on a regular basis to discuss the diagnosis and treatment plans for patients. The need for regular communication was also identified by Dahlke et al. (Reference Dahlke, Meherali, Chambers, Freund-Heritage, Steil and Wagg2017) as key to supporting interprofessional collaborations among care teams. An issue related to communication among team members, but unique to rural settings, was how specialist teams and the referring family physician interacted. In some cases, the family physician was reluctant to engage with the specialist team (Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Wilcock and Haworth2006; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Crossley, Kirk, D’Arcy, Stewart, Biem and McBain2009). However, Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014) demonstrated that when the primary care physicians engaged in ongoing communication and received support from specialists, they were more confident and efficient in diagnosing and treating patients with local supports and resources. This approach is supported by the World Alzheimer Report 2016 (Prince et al., Reference Prince, Comas-Herrera, Knapp, Guerchet and Karagiannidou2016), which identified the need for low-resource rural areas to build capacity through training of primary care staff and to connect patients with local services. Moreover, engaging the family physician directly thereby links to the most common factor identified at the organizational level, which was access to systematic and comprehensive training and education for all team members.

Similar findings have been reported in studies employing telehealth approaches to diagnosing and treating dementia among rural residents. For instance, the training of local health professionals in rural communities was deemed essential to ensure that telehealth tools are implemented effectively (Barth et al., Reference Barth, Nickel and Kolominsky-Rabas2018). In addition, training to increase education and knowledge among local primary care teams was linked to increases in patient satisfaction (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Morris, Rothlind and Yaffe2011; Lee, Hillier, Heckman, et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014; Lee, Hillier, & Weston, Reference Lee, Hillier, Heckman, Gagnon, Borrie, Stolee and Harvey2014).

At the systems level, the most commonly identified factors included human and financial resources to support ongoing collaborations among care teams. These findings were similar to those reported by Dahlke et al. (Reference Dahlke, Meherali, Chambers, Freund-Heritage, Steil and Wagg2017) wherein low staffing levels were identified as a barrier to ongoing implementation of collaborative team-based approaches to care. A factor related to human and financial resources was that rural and remote communities often lacked the population base to support hiring a wide range of health care professionals and specialists. Adding to this challenge was the high rate of staff turnover, particularly among primary care physicians in rural communities (McGrail, Wingrove, Petterson, & Bazemore, Reference McGrail, Wingrove, Petterson and Bazemore2017; Pong & Pitblado, Reference Pong and Pitblado2005). High turnover resulted in added burden on primary health care team members, particularly when they were required to take on additional roles for which they did not have sufficient training and education.

The combined findings and literature gaps identified in this scoping review have research, practice, and policy implications.

Recommendations for Research

Future research should focus on reporting the specific definition of rural employed in the study; in addition, a detailed description of the rural setting in which the study was conducted should be provided. The provision of such contextual information will assist the reader in determining if the reported findings are transferable to other rural environments.

A second recommendation for future research is the step-by-step documentation of specific processes that local interprofessional PHC teams engage in when they are diagnosing and delivering treatment to rural and remote residents living with dementia. This includes developing an understanding of how specialists in urban areas and PHC professionals in rural settings collaborate in task sharing, with the goal of supporting primary care teams to build capacity and take on a leadership role in the diagnosis and treatment of dementia (Prince et al., Reference Prince, Comas-Herrera, Knapp, Guerchet and Karagiannidou2016). Combined, this information will inform the development of a dementia primary care model, which incorporates best practices specifically tailored to the unique needs of rural and remote residents being cared for in their local community. Finally, future research in this area should include a focus on identifying and exploring sex and gender differences that influence how PHC teams collaborate to support rural residents living with dementia.

Recommendations for Practice

When health care professionals engage in team-based care, it is important that they take time to define and understand the type of team they are attempting to establish (e.g., interdisciplinary/interprofessional vs. multidisciplinary/multiprofessional). From the outset, these teams should identify a common purpose, performance goals, and mechanisms for facilitating communication and collaboration. This includes establishing a team lead and identifying team roles and responsibilities. Developing such protocols will support rural PHC teams in building capacity and becoming more proficient in diagnosing and treating dementia. In addition, rural-based PHC teams, which are often not co-located, need to have additional mechanisms in place to aid in relationship building and promote both formal and informal interactions. Further, rural PHC teams should work collaboratively with specialist teams (typically located in urban areas) to develop skills in diagnosis and treatment of persons with dementia. Moreover, a mechanism should be in place to support PHC teams in referring more complex cases to a specialist team. In turn, this would increase the availability of specialist services for more complex dementia cases.

Recommendations for Policy

The findings of this scoping review may be used to inform policy development, particularly among local rural health authorities. Specifically, local governance should develop guidelines for facilitating collaboration among multiple health care professionals while simultaneously addressing system-level barriers identified by team members. In addition, health authorities should be responsible for ensuring that resources are in place to provide all necessary training for all team members, including additional supports for those in team leadership roles. Finally, local governance should establish protocols for prioritizing patient engagement during the development and implementation of any rural PHC model for dementia care. Ensuring a person-centred approach is at the core of all rural PHC teams caring for persons with dementia.

Limitations

Limitations identified in this study include the elimination of grey literature which potentially contained relevant information; as a result, literature beneficial to this scoping review may have been missed. A second limitation is that our review included only English-language publications. A further limitation is that given the nature of the scoping review process, included articles were not assessed for quality and rigor. All included studies, however, were published in peer-reviewed journals; furthermore, each article was assessed by two reviewers to ensure that the reported content was relevant to the scoping review aim and objectives. Finally, due to the lack of information about sex and gender among the articles included in this scoping review, we were unable to address and explore sex and gender differences as they related to both delivery of care and how PHC functions in delivering that care.

Conclusion

Overall, this scoping review has contributed to a better understanding of the diverse team compositions that are employed to diagnose and treat dementia in rural and remote settings. Key factors (barriers and facilitators) shown to influence how teams collaborate to deliver dementia care to rural and remote residents were identified. Moreover, four of the included articles detailed the specific processes local PHC teams employed to deliver collaborative and comprehensive dementia care to residents living in rural and remote areas. Moving forward, we plan to engage with rural PHC teams to further understand how teams are implementing collaborative care approaches for rural residents living with dementia and other chronic conditions. In addition, the findings from this review are being used to inform the development of a rural and remote PHC dementia model. Specifically, applicable processes identified in the current scoping review will be incorporated into the model and evaluated for their effectiveness in supporting team-based PHC for rural residents living with dementia. Combined, this will result in a PHC model consisting of evidence-based best practices for rural dementia care.