Canada’s current hospital-focused care system continues to be best suited for acute and short-term use (Allen, Hutchinson, Brown, & Livingston, Reference Allen, Hutchinson, Brown and Livingston2014), despite the exponential increase in the number of older adults and the proportion of older adults living with complex health care needs (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2002). The mismatch between a growing older adult population with complex care needs and a system focused on singular, acute conditions results in: (1) challenges with ensuring effective discharge processes and the provision of timely and adequate care post hospital stay (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Hutchinson, Brown and Livingston2014); and (2) older adults typically being discharged prior to full recovery and achievement of rehabilitation potential and without proper supports in the community (Comans, Peel, Gray, & Scuffham, Reference Comans, Peel, Gray and Scuffham2013). These challenges are reflective, in part, of patient-level factors and health care system barriers. Patient-level factors such as new limitations in activities of daily living developed during hospitalization, difficulty in managing chronic conditions, and cognitive impairments often require an increased level of and need for ongoing support and services (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Hutchinson, Brown and Livingston2014). Health care system barriers such as breakdown in communication among delivery levels, inadequate provision of patient and caregiver information, poor continuity of care, and limited access to community services (Kiran et al., Reference Kiran, Wells, Okrainec, Kennedy, Devotta and Mabaya2020) lead to negative consequences including medication errors, increased health care costs, hospital readmission rates and institutionalization rates, and decreased quality of care and quality of life for both the older adults and their caregivers (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Hutchinson, Brown and Livingston2014; Mansukhani, Bridgeman, Candelario, & Eckert, Reference Mansukhani, Bridgeman, Candelario and Eckert2015; Verhaegh et al., Reference Verhaegh, MacNeil-Vroomen, Eslami, Geerlings, de Rooij and Buurman2014).

Properly planned and conducted transitional care interventions can decrease hospital readmission rates and emergency department visits and improve older adults’ quality of life (Naylor, Aiken, Kurtzman, Olds, & Hirschman, Reference Naylor, Aiken, Kurtzman, Olds and Hirschman2011; Verhaegh et al., Reference Verhaegh, MacNeil-Vroomen, Eslami, Geerlings, de Rooij and Buurman2014). A “transitional intervention” has been defined as any intervention that promotes safe and timely transfer of patients among levels of care and across care settings (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Hutchinson, Brown and Livingston2014). Some transition interventions take place when the older adult is in the hospital (pre-discharge strategies), and may include discharge planning and medication reconciliation. Other interventions, such as education about chronic disease management, home visits, and follow-up phone calls, target the post-discharge time frame (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Hutchinson, Brown and Livingston2014) A meta-review assessing discharge interventions in developed countries found that patient and caregiver education were the most beneficial for improving older adults’ emotional status and decreasing hospital readmission rates (Mistiaen et al., Reference Mistiaen, Francke and Poot2007). Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Hutchinson, Brown and Livingston2014) found that interventions led by multidisciplinary teams and involving the patient had the greatest impact on decreasing hospital readmission rates and improving quality of life. Other interventions and elements, including care planning, communication among providers, preparation of the patient and caregiver, reconciliation of medications, community-based follow-up, and patient education about self-management have also been found to be essential to successful transitions (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Hutchinson, Brown and Livingston2014).

Interestingly, research has found that currently available frameworks for care transitions for older adults are lacking specific mention of integrated community programs that include occupational therapy or physiotherapy specifically, or rehabilitation and rehabilitation professionals in general (Kalu, Maximos, Sengiad, & Dal Bello-Haas, Reference Kalu, Maximos, Sengiad and Dal Bello-Haas2019). Available programs often lack some of the necessary coordination and provision of post-discharge services that may bridge the transition between hospital discharge and initiation of community services (Falvey et al., Reference Falvey, Burke, Malone, Ridgeway, McManus and Stevens-Lapsley2016; Watkins, Hall, & Kring, Reference Watkins, Hall and Kring2012). Specifically, nutrition support, transportation, and the provision of support services for instrumental activities of daily living are typically lacking (Watkins et al., Reference Watkins, Hall and Kring2012). Community-based, slow-stream rehabilitation (SSR) hospital-to-home transition programs may be a model of care that provides the much-needed support for older adults following an acute hospital stay. SSR programs are structured to be multidisciplinary, longer in overall program duration, but with shorter duration and lower intensity sessions, and are therefore ideal for older adults who are frail or who have complex multiple health conditions (Maximos, Seng-iad, Tang, Stratford, & Dal Bello-Haas, Reference Maximos, Seng-iad, Tang, Stratford and Dal Bello-Haas2019). These programs have been shown to improve physical abilities and independence with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living among older adults, as well as decreasing hospital readmissions (Maximos et al., Reference Maximos, Seng-iad, Tang, Stratford and Dal Bello-Haas2019).

As part of a comprehensive evaluation of a community-based, SSR, hospital-to-home transition program for older adults, we were interested in learning more about specific program processes and practices and any real or potential program process and practice-related gaps, stumbling blocks, and enablers. Therefore, the purpose of this qualitative descriptive study was to examine the perspectives of care providers working in or referring to the program to identify factors that may act as barriers to or facilitators of successful implementation and functioning of a community-based, SSR, hospital-to-home transition program.

Methods

Study Design

This was a qualitative description study, with methods conducted as described by Sandelowski (Reference Sandelowski2010), which aimed to describe and identify a phenomenon through naturalistic inquiry from a social constructivist view (Bradshaw, Atkinson, & Doody, Reference Bradshaw, Atkinson and Doody2017; Willis, Sullivan-Bolyai, Knafl, & Cohen, Reference Willis, Sullivan-Bolyai, Knafl and Cohen2016). Qualitative description is used when the aim of the researcher is to present facts but not to interpret the data in terms of perceptions, emotions, or the philosophical underpinnings of those interviewed (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2010).

Study Context

The community-based, SSR, hospital-to-home transition program was designed to assist older adults with continued rehabilitation and other health-related needs to enable them to return to independent living in the community (home) after discharge from an acute care hospital stay or from an inpatient rehabilitation or convalescent care program. The program was developed as a day program; for example, participants attend the program during the day and return home daily allowing them to recover in their own homes, while receiving nursing, physiotherapy, recreation, and other health care professional interventions and support such as pharmacy and occupational therapy. The program was considered SSR as it provides lower-intensity rehabilitation for shorter durations of time. At the time of the study, participants attended the program from Monday to Friday for 1 month and completed a variety of activities each day, including individual and group exercises and social and cognitive activities. Participants received group-based and one-on-one education on an array of topics, such as falls prevention, nutrition, and managing polypharmacy. Snacks and a mid-day meal were provided, as was transportation to and from the program. After the 30 days, the older adult was discharged from the program and could be referred to other community-based programs or support services if and as needed.

At the time of the study, the program was located in one of the 14 Local Health Integration Networks responsible for planning, integrating, and funding health care, as well as for delivering and coordinating home and community care, based on local needs. The discharge process from hospital to community in the LHIN that housed the program at the time of the study was facilitated by hospital-based case coordinators. These care coordinators and LHIN community-based care coordinators referred older adults to the program.

Participant Criteria and Recruitment

The aim of qualitative description is to generate a rich descriptive database of different perspectives and major themes (Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Atkinson and Doody2017). Therefore, a sample of care providers with diverse disciplines working within or referring to the program was recruited. Recruitment was conducted through purposive sampling, which is a technique that involves intentionally sampling a group of people who can best inform the researcher about the phenomenon of interest (Creswell & Poth, Reference Creswell and Poth2016). Participants were included if they were directly involved with or had experience with the care of older adults in the program or were directly involved with or had experience with referring older adults to the program. Those identified as potential study participants included individuals working within the LHIN as case coordinators, working within complex continuing care or convalescent care, and directly working within the program. Potential participants were sent a recruitment letter via e-mail or mail and were asked to contact the project coordinator if they were interested in setting up a phone or in-person interview or attending a focus group. In keeping with the methodology for qualitative studies, no sample size was calculated (Creswell & Poth, Reference Creswell and Poth2016), and participant recruitment was conducted until a wide array of individuals were interviewed and themes occurred more than five times.

Data Collection

Individuals participated in one of two focus groups (n = 11) or an individual semi-structured interview (n = 12) based on personal preference. Focus groups were conducted in person by two researchers at the program location and were approximately 1 hour in length; individual semi-structured interviews were conducted either in person or via telephone and were approximately 30–60 minutes in length. For both data collection methods, researchers used semi-structured interview guides composed of the same introductory information and the same open-ended and probing questions related to needs and strengths of, concerns about, and challenges with current program services. Interviews and focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Researchers identified themselves as research assistants who were facilitators rather than topic experts, in order to allow for neutrality and objectivity when collecting data (Willis et al., Reference Willis, Sullivan-Bolyai, Knafl and Cohen2016). Also, researchers recorded observation notes, field notes, and reflexive notes about perspectives, reactions, and feelings that arose during focus groups or semi-structured interviews. These notes were also transcribed and were used to further enhance the transparency of the analysis and the validity of results (Creswell & Poth, Reference Creswell and Poth2016).

Data Analysis

All interview transcripts were analyzed using data-driven inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2014), a type of analysis that is free from theoretical frameworks and researchers’ analytical preconceptions. This analysis aims to identify, analyze, and report patterns within data (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Thematic analysis was completed by six researchers in independent pairs. During the coding process, each researcher kept reflexive journals to document their ideas and thoughts. For each transcript, researchers followed the six steps of thematic analysis guideline described by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006), which involves initially conducting an independent analysis of the transcript consisting of reading the transcript to familiarize themselves with the information, then generating codes through line-by-line reading, and then generating themes from the data. If needed, researchers referred to observation, field and reflexive notes taken during the interviews, or focus group to further contextualize codes and themes. Once the researchers reviewed the transcript and generated themes individually, they then met with their pair-partner to review and resolve any discrepancies collaboratively through discussion. All six researchers met midway through the review process and all transcripts were reviewed to discuss findings and resolve discrepancies in code books. This was done to triangulate all codes and themes to derive a final coding book. Themes were then presented to the broader multidisciplinary research team members who were not involved in the coding process for further analysis and feedback. The code book was then adjusted according to feedback (e.g., fit of themes, potential areas of over-interpretation of data). This triangulation process with the larger research team occurred multiple times until a final agreed-upon code book was developed.

As part of the thematic analysis, an overarching examination of the themes that emerged from the inductive approach used was conducted. Themes that emerged were organized based on an underlying structure that became evident, specifically a socio-ecological framework structure that highlights multiple levels of impact, influence, and interactions: macro-meso-micro levels of health care systems – patient level (micro), health care organization and community level (meso), policy level (macro) (World Health Organization, 2002); and health care priority setting levels – macro-level (national, provincial), meso-level (regional, institutional), and micro-level (clinical program) (Kapiriri, Norheim, & Martin, Reference Kapiriri, Norheim and Martin2007) (Tables 1–3). Macro-meso-micro level terminology and framework structure have been used in an array of research including policy research (e.g., Kapiriri et al., Reference Kapiriri, Norheim and Martin2007), scope of practice research (e.g., Smith, McNeil, Mitchell, Boyle, & Ries, Reference Smith, McNeil, Mitchell, Boyle and Ries2019), and community intervention research (e.g., Otiso et al., Reference Otiso, McCollum, Mireku, Karuga, de Koning and Taegtmeyer2017; Valentijn, Schepman, Opheij, & Bruijnzeels, Reference Valentijn, Schepman, Opheij and Bruijnzeels2013) to describe and understand a phenomenon of interest using a macro-, meso-, micro-level framework to identify potential areas where barriers and facilitators exist.

Table 1. Facilitators of and barriers to enhancing and implementing a community-based, hospital-to-home slow-stream rehabilitation program at the macro level

Table 2. Facilitators of and barriers to enhancing and implementing a community-based, hospital-to-home slow-stream rehabilitation program at the meso level

Ethical Considerations

Participants were informed of the research aims and provided with written informed consent. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board. Specific names and locations that appeared in participants’ transcribed comments were replaced with a pseudonym to ensure anonymity.

Results

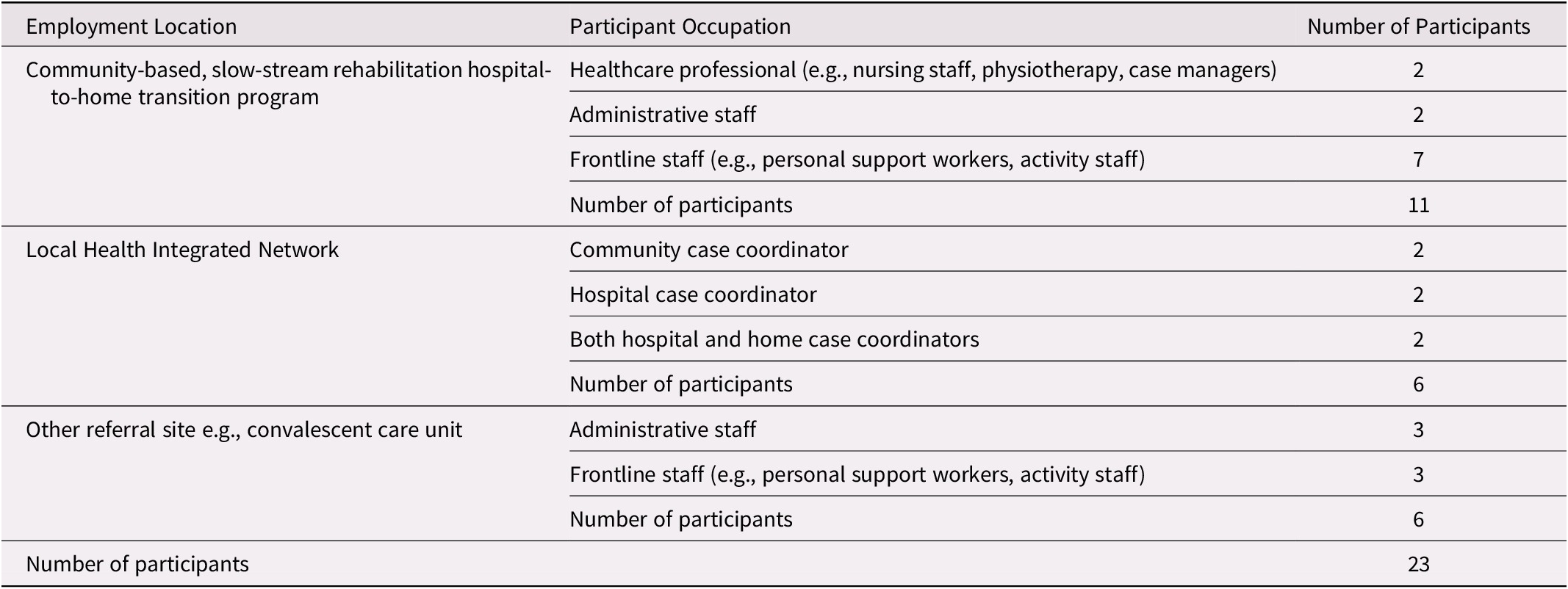

Twelve semi-structured interviews and two focus groups (n = 11) were conducted with a total of 23 participants (see Table 4 for participant information). Six participants were employed by the LHIN, 6 were employed by other referral sites, and 11 were employed in the program.

Table 3. Facilitators of and barriers to enhancing and implementing a community-based, hospital-to-home slow-stream rehabilitation program at the micro level

Table 4. Employment Location and occupations of participants

An overarching theme was time, with three distinct time points identified by study participants as important: before program admission; that is, before older adults begin the program; during the program; and following program completion. Some themes extended across all time points, whereas others were bound to a particular time point (Figure 1 provides an overview of themes).

Figure 1. An overview of over-arching themes and sub-themes categorized by socio-ecological framework: macro, meso, and micro levels. All themes have been categorized into macro, meso and micro levels, and the interaction among the levels has been identified through the directions of the arrows. Changes in macro level barriers will directly impact resources available for knowledge dissemination and communication among service delivery levels at a meso level and will impact the program structure constraints and services available at a micro level. In turn, changes at a micro level such as improving use of outcome measures in the program or implementing a Web site for the program will in turn affect all the barriers seen at a meso level, and may improve resource allocation at a macro level. (-) indicates that the theme was considered a barrier to and (+) indicates that the theme was considered a facilitator of enhancing and implementing a community-based, hospital-to-home, SSR program.

Macro-Level Factors

Macro-level factors have been described as federal or provincial-level factors (Kapiriri et al., Reference Kapiriri, Norheim and Martin2007), such as policy, resource allocation, funding for supports and services, and initiatives (World Health Organization, 2002) to support older adults post-hospitalization. Participants described the current lack of resource allocation and funding for hospital-to-home transition supports and services as barriers to further program development. This lack of resource allocation and funding extended across all three time points. Although the program provided specific supports and services at a particular point in time post-hospital discharge, what transpired before and after the program were also highlighted as elements important to consider for a comprehensive model of care for hospital-to-home transition for older adults. No macro- level facilitators were identified. Macro-level themes included: gaps while waiting for program, limited program capacity and need for expansion of program services, and gaps in service following program completion.

Gaps while waiting for the program

Program participant (older adult) needs prior to admission into the program encompassed services that would support the older adult post-hospital discharge and were often unmet. Gaps, in other words lack of continuity of care, included lack of availability of home care support and health education, as well as lack of timely and continued rehabilitation including occupational and physiotherapy. These gaps were discussed by both referral and program staff as impeding older adult success in the program. Participants noted that there are currently very few to no resources, supports, and services available post-hospital discharge to prevent loss of any gains made while hospitalized and to prevent loss of independence while the older adult is waiting to be admitted into the community program. “Um, recognition that the service is needed right away and it may be short term but they need it when they leave the hospital, not after a period of time” (P11).

Limited program capacity and need for expansion of program service

A barrier was that the current capacity of the program was limited both in terms of the number of older adults that could be admitted at any one time as a result of lack of funding and the challenges related to capacity within the program. This barrier hindered program delivery because limited exercise equipment resulted in wait times for equipment, having to share equipment with participants in other programs offered by the facility, and the ratio of number of staff to number of older adults in program. Growth in the number of programs across regions was identified by study participants as a method of enhancing the model of care by allowing for greater access to hospital-to-home transition programs.

You’ve got a lot of competing programs that need to use a fixed number of machines, and that can be a challenge for sure. (P2)

It would be nice if there were more programs like [program], even if the VON could do something like that but it would be great because that program is west [location] and you’ve got [multiple locations of interest] in this whole area. I don’t know about [another location] and all those areas but even in our area there’s only one location so somebody in [far location], they’re not going to want to do that drive and [program] would not be able to do that, get everybody there on time. (P9)

Gaps in service following program completion

The lack of available low-cost or no-charge community-based programs and services that would support gains made and assist with continuity of care was considered a health care gap that could lead to potential loss of benefits that were made during the community program. Programs were either not available in general or not available in the older adult’s community or were too costly. Participants expressed concern about the lack of these important community resources and what would happen to the older adult’sphysical and emotional well-being after discharge from the program.

[in program] They get exercises, it’s free of cost…. Then, at the end of 30 days, you pull the rug out. It tells them that there is hope and things can change, but then many of them do not have the resources to make it happen. (P3)

Meso-Level Factors

Meso-level factors exist at the health care organization and community level (World Health Organization, 2002) or the regional level (Kapiriri et al., Reference Kapiriri, Norheim and Martin2007). Kapiriri et al. (Reference Kapiriri, Norheim and Martin2007) described meso-level factors as being priorities within the organization and its related community sources. Examples of meso-level factors can include tools within and between care delivery levels, knowledge and expertise of staff, and values and priorities of the larger organization of interest (Kapiriri et al., Reference Kapiriri, Norheim and Martin2007; World Health Organization, 2002). Meso-level themes identified in this study included: lack of knowledge and awareness of the program, lack of specific referral process and procedures, lack of specific eligibility criteria, and need for enhanced communication among care settings, and all were deemed areas of improvement to be implemented to enhance the model of care. No meso-level themes were identified as facilitators.

Lack of knowledge and awareness of the program

This theme comprised lack of understanding of the services provided by the program and not having information about the program to distribute to other staff members or potential program participants. Lack of knowledge and awareness were perceived as a barrier mainly by referral staff and program leadership. The study participants indicated that they did not have access to information pamphlets and only knew that the program existed through “word of mouth”. Because of the high turnover of care coordinators, program knowledge and awareness often disappears when the care coordinator leaves. In addition, those who knew of the program’s existence indicated difficulty identifying all the different elements and components or the goals of the program.

We have a lot of changes in staff so there’s always a possibility that newer staff are not aware of [program]. (FG1)

I could use some brochures (Laughter). I steal some from the social worker and physio but typically the physio and the social worker have brochures and give it to them. (P12)

Lack of specific referral process and procedures

The lack of specific referral processes and procedures was viewed by study participants as an area needing improvement, which led to barriers in regard to who was admitted to the program and how to provide access to the program. Specifically, the lack of a defined set of actions to be undertaken to transfer participant information from one level of care to the program and the lack of a paper trail for referrals resulted in uncertainty about how to refer to the program, when to refer to the program, and whether the referral was actually received by the program. Also, the general referral process used differed based on whether the referral was from a community care coordinator, the hospital care coordinator, or individuals from other sites such as convalescent care. The referral process was often dependent on whether the staff referring the prospective older adult participant knew whom to contact.

…however, another negative is that we’re not properly instructed there’s no referral base in our computer system to indicate that this person has been referred to [program]… (P10)

Lack of specific eligibility criteria

The need to have a better understanding of the characteristics of potential older adult participants who would most benefit from the program was identified as important by referral and program staff. Both the program and referral staff discussed the need to use standardized measures and cut-off values as a potential way to ensure appropriateness of referrals. The referral staff noted that they had a general idea of who would most benefit from the program, but did not have a clear understanding of any eligibility criteria. This led to some confusion and inappropriate referrals to the program.

So actually looking at the criteria, because it’s so wide, “well, you’ve had to have a hospitalization within the last 3 months”, and almost anyone can say “well I’ve been in the hospital”. So I would like to see that the eligibility criteria is more specific to who’s appropriate and who’s not appropriate.(P2)

I think [The program] is designed for people but a certain level of independence and ability to follow through on commands and able to benefit from the program. (P11)

Need for enhanced communication among care settings

Written or spoken communication should take place any time patient information has to be moved from one level of care to another or from a care setting to the program. For example, communication could take place between community level and the hospital (e.g., community case coordinators and hospital discharge staff) or between community settings (e.g… program staff and LHIN staff). Study participants discussed the need to enhance methods of communication among service delivery levels to increase knowledge about patient’s medical status, decrease lag time for information sharing, and increase clarity of communication. Communication issues were viewed as barriers that needed to be addressed.

It’s not up to us it’s up to the LIHN because I have this conversation with the care coordinator sometimes they are already on the list sometimes they were sent back from another transitional bed program to the hospital that has requirements for our program so… Or if not, when they are in here they will have a file opened for them and then they go through the same process. (FG3)

Micro-Level Factors

Micro-level factors include patient-level factors and day-to-day program components that either support or hamper individual empowerment, such as communication with the patient, patient goals, and program structure (Kapiriri et al., Reference Kapiriri, Norheim and Martin2007; World Health Organization, 2002). Most of the participants noted micro-level factors as important components to maintain. Themes included services provided, program participant benefits, and person-centred communication. Study participants noted program structure constraints, need for utilization of outcome measures, and lack of follow-up as hindering program participant long-term success.

Services provided

A variety of program activities, education, care, and supports were provided to older adult participants. The following were considered components that should be retained, built upon, and expanded: multidisciplinary care, free transportation to and from the program, provision of meals, health and nutritional education, social activities, and rehabilitation.

Its free, transportations provided, meals provided, physio-focused, they have to have goals, and then I think that they offer some additional services like a shower or foot care. (P11)

Program participant benefits

Study participants identified that program participant benefits were directly related to program activities, and included increased physical function, improved mobility, and increased endurance, as well as decreased isolation and depression. Some intrinsic benefits included renewed sense of meaning, motivation to continue to be active, and motivation to be engaged in their community.

I think also knowing that they can improve, it just reminds them that hey I can improve later, it’s possible that I can keep going so it just gives them more intrinsic motivation to continue on with other programs. (FG1)

…back to the full body abilities, so there’s the rehabilitation piece which takes into account your mind, body, spiritual, all the various assets to helping that rehabilitation model. (P2)

Person-centred communication

Person-centred communication is a method of gathering or providing a two-way stream of information sharing between staff and participants or their families in a way that is empathetic and AUaccommodating of individual’s beliefs, desires, knowledge, and experiences (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Perkhounkova, Jao, Bossen, Hein and Chung2018). Person-centred communication was evident and was engaged in across all time points by referral and program staff. All study participants discussed the importance of continued person-centred communication as a critical component of any model of care.

Prior to the start of the program referral, staff met with family and prospective participants about the program and rehabilitation goals. During the program, program staff provided emotional support and developed relationships with the older adult participants. Program staff described being open and having a willingness to listen to the older adult program participants’ opinions and needs. This openness and willingness to listen continued during discussions of linking older adults and their families with community resources.

Yes. So we have that family meeting in convalescent care when we discuss the progress and discharge destination…on day 45 you know what, this patient needs to be here for like, up to 90 days because we don’t see that going home sooner than 90 days so the family knows, this is the day that is for potential discharge so they are planning everything ahead… (P7)

So the [occupation of program staff member] who’s in there, [Name], really takes a real personal approach with each person, really helps make them feel acknowledged and accommodated as best she can. We try to get all the variable information that’s necessary to make their experience as positive as possible. (P2)

Program structure constraints

Program structure included elements that comprised the design of the program such as total length of the program, daily schedule, and time spent in the program per day. Program and referral staff discussed that not all older adult program participants progressed at the same rate and that the 30-day program length was a limitation for some older adults. Study participants highlighted the need for more flexibility, such as having a step-down approach where after the 30-day program, participants could continue three times a week and then twice a week and then once a week for a limited time. Because of individualized needs, some older adult participants would have benefited from being able to attend the program for half days rather than full days. Participants also indicated they would have liked the ability to re-enter the program should issues arise, or be able to stay in the program for an extended period of time, beyond the 30 days.

Timing doesn’t work for everyone because it is a morning program. If there were two different streams, a morning and afternoon, it would be beneficial to a lot of the population who’s not able to get up so early and have their PSW come and assist them… (P10)

I think it should be tapered maybe, so you get this lovely one month program and then you’re done, can you, you know, ween it down to bi-monthly, you know or, like a step-down program so that it sort of prepares them and educates them about other resources in the community um, I don’t know if you would want to call it a coach but somebody just to say what’s your quality of life? How are things at home? What else would you like to be doing? Sort of the navigator. (P14)

Need for use of outcome measures

Using standardized tools with cut-off values that could objectively measure older adults’ physical ability, psychological well-being, and ability to complete activities of daily living was viewed as important. Study participants stated that the implementation of standardized measures in a model of care would be beneficial for communicating patient progress and needs among different care settings, as well as would providing evidence to support the need for the program, to sustain current funding levels, and to advocate for increased expansion and funding in the future.

If they generated a mini assessment, like an ADL or some kind of measure of what their abilities were… and then did an ability summary assessment that would be kind of beneficial. (P9)

Need for continued follow-up by program or referral staff

Study participants stated that once the program was completed, there was no further follow-up with the older adults to determine if the recommendations were implemented. Both program and referral staff participants stated that having opportunities to maintain communication with older adult participants after program completion would be beneficial, may enhance longer-term benefits, and could potentially identify new challenges that arise for older adults post-program completion sooner rather than later.

… I don’t know if they have any support that’s… I don’t really ask and I… I really have no idea what is happening after that one month. Do they have any support? Of course, they have like services if they are eligible from LIHN but what about the physio you know? The physio I think is the key. (P7)

Discussion

SSR programs, designed to provide optimal care for older adults with complex health care needs or who are not able to participate in “traditional” rehabilitation programs, are available in institutionalized settings across Canada (Maximos et al., Reference Maximos, Seng-iad, Tang, Stratford and Dal Bello-Haas2019) to address activities of daily living and mobility problems, prevent institutionalization, and decrease hospital readmission. No study to date has evaluated the transition process from hospital or convalescent care to a community-based, SSR, hospital-to-home transition program from the perspective of a multidisciplinary care team, which led to this study.

Perhaps not surprisingly, most of the stated barriers and gaps were at a macro or meso level and were out of the study participants’ control, whereas all the facilitators were at a micro level. Study participants emphasized the importance and role that community hospital-to-home transition programs for older adults play in decreasing institutionalization and allowing for return to independent living post-hospitalization. However, macro and meso level factors such as limited government resource allocation, lack of knowledge about the program, need for more well-defined referral processes and communication across service delivery levels were considered barriers that would need to be addressed for further program development, implementation and success. Many of the barriers of care identified in this study are similar to those previously reported by policy researchers, healthcare workers, family caregivers, as well as older adults themselves: break-down between care delivery levels (Mansukhani et al., Reference Mansukhani, Bridgeman, Candelario and Eckert2015), lack of community-based follow-up (Russell, Skinner, & Fowler, Reference Russell, Skinner and Fowler2019), limited access to services and resources; and specifically in Ontario, lack of timely services and community supports, limitations of funded services and coordination of care (Kiran et al., Reference Kiran, Wells, Okrainec, Kennedy, Devotta and Mabaya2020).

In 2007, the government of Ontario proposed a provincial ‘Aging in Place’ initiative that would enable older adults to continue leading healthy, independent lives in their own home. This initiative aimed to provide $1.1 billion over four years with an increase of $143.4 million for community-based programming in the first year alone (Peckham, Rudoler, Li, & D’Souza, Reference Peckham, Rudoler, Li and D’Souza2018). The program goals were to improve coordination of services from hospital to community and support initiatives that would decrease emergency department and alternative level of care usage. This led to multiple LHIN-funded initiatives across different regions of Ontario (Peckham et al., Reference Peckham, Rudoler, Li and D’Souza2018). However these initiatives are at the provincial level and are not part of Canada’s Medicare system, and thus lack universal, sustained funding for building capacity in the community (Peckham et al., Reference Peckham, Rudoler, Li and D’Souza2018). Competing political agendas have resulted in fragmentation within the community and social care subsectors (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Skinner and Fowler2019). Community initiatives are often motivated by a single funding injection and thus long-term sustaining of initiatives becomes difficult when funding is withdrawn (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Skinner and Fowler2019). Russell et al. (Reference Russell, Skinner and Fowler2019) suggest that a top-down approach rather than bottom-up approach to coordination of funding is needed, which would allow for sustained programming and planning with communication and collaboration directly with policy makers. An analysis conducted by Russell et al. (Reference Russell, Skinner and Fowler2019) found that in order to maintain sustainability of community initiatives community champions, multi-disciplinary and cross-sector collaborations, and systemic municipal involvement are required.

In addition to sustainability, communication across system delivery levels requires cross-system talk between different medical record platforms, otherwise sharing of information is difficult to coordinate (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Skinner and Fowler2019). Communication issues across service delivery levels is not unique to Ontario or the Canadian health care system, but has also been highlighted in the United States and in Europe (Mansukhani et al., Reference Mansukhani, Bridgeman, Candelario and Eckert2015; Vermeir et al., Reference Vermeir, Vandijck, Degroote, Peleman, Verhaeghe and Mortier2015) and include lack of time for spoken communication or secure systems for indirect communication, such e-mail, referral documents, and availability of assessment information among home care, rehabilitation staff, and acute care providers. In the United States, systems and tools have been developed to share patient information across care delivery levels. The Continuity Assessment Records and Evaluation platform is an example of such a tool, intended to provide up-to-date and accurate information at the time of hospital discharge and during the transition of care period (Mansukhani et al., Reference Mansukhani, Bridgeman, Candelario and Eckert2015). Platforms such as these have been shown to decrease hospital readmission rates, improve quality of care and patient involvement, and decrease overall health care costs (Mansukhani et al., Reference Mansukhani, Bridgeman, Candelario and Eckert2015; Vermeir et al., Reference Vermeir, Vandijck, Degroote, Peleman, Verhaeghe and Mortier2015).

In contrast to the barriers, all facilitators were either related to day-to-day program activities or to the program structure. Micro-level facilitators identified included the services available to older adult participants, person-centred communication, and extrinsic as well as intrinsic gains directly related to program design. According to the study participants, the program was successful because it combines rehabilitation, nutrition, and education with opportunities for social interactions and the ability to seek guidance from an array of health care professionals. Integrated care at a micro level, where a program or clinic provides a multidisciplinary care team and multifaceted programing to assist older adults with multiple chronic conditions or functional limitations, is an often used as a framework for patient care (Briggs, Valentijn, Thiyagarajan, & de Carvalho, Reference Briggs, Valentijn, Thiyagarajan and de Carvalho2018). Many of the facilitators are similar to those documented in the SSR program (Maximos et al., Reference Maximos, Seng-iad, Tang, Stratford and Dal Bello-Haas2019) and community-based program literature (Berger, Escher, Mengle, & Sullivan, Reference Berger, Escher, Mengle and Sullivan2018; Kjerstad & Tuntland, Reference Kjerstad and Tuntland2016; Shumba, Haufiku, & Mitonga, Reference Shumba, Haufiku and Mitonga2020). Yet to date, SSR programs have been solely housed in institutionalized settings such as hospitals and long-term care facilities (Maximos et al., Reference Maximos, Seng-iad, Tang, Stratford and Dal Bello-Haas2019). SSR programs provide an array of services for the older adult with complex health care needs, often via a multidisciplinary care team, and have been shown to successfully improve function and decrease institutionalization and hospital readmission (Maximos et al., Reference Maximos, Seng-iad, Tang, Stratford and Dal Bello-Haas2019). The multidisciplinary structure and array of services are considered important in both SSR and community-based programs, as is the ability to provide the education and skills to both the older adult and their family caregivers that are needed for independent living (Maximos et al., Reference Maximos, Seng-iad, Tang, Stratford and Dal Bello-Haas2019).

Services that study participants described as being important to the success of older adults transitioning back to independent living post-hospitalization and that should continue in any future program included nutrition, transportation to and from the program, socialization opportunities, and rehabilitation services. Previous literature has shown that provision of services such as nutrition, education about chronic conditions and management, transportation or access to community services (e.g., grocery, gyms, coffee shops), and access to home care supports have been associated with maintained physical function, improved mental health, improved quality of life, and a reduction in emergency department use for older adults living independently in their homes (Falvey et al., Reference Falvey, Burke, Malone, Ridgeway, McManus and Stevens-Lapsley2016; Jeste et al., Reference Jeste, Blazer, Buckwalter, Cassidy, Fishman and Gwyther2016). Rehabilitation services such as physiotherapy have also been found to decrease hospital readmission and improve physical function for older adults with complex health care needs (Falvey et al., Reference Falvey, Burke, Malone, Ridgeway, McManus and Stevens-Lapsley2016). Interventions aimed at improving functional difficulties and focusing on reducing risk factors related to co-morbidities (eg. education or medication management) have been shown to improve health and decrease hospital expenditure (Smith, Soubhi, Fortin, Hudon, & O’Dowd, Reference Smith, Soubhi, Fortin, Hudon and O’Dowd2012). These findings, as well as the findings of previous policy statements, the World Health Organization highlights the need for major reforms to health care systems to support an aging population through the integration of health and social services to address prevention and management of declining functional ability in older adults (Briggs et al., Reference Briggs, Valentijn, Thiyagarajan and de Carvalho2018; World Health Organization, 2015, 2016).

The study participants also discussed aspects that were not directly related to program resources but rather were related to communication with older adult clients and their families. Study participants felt that person-centred communication and collaboration with the clients and their families were vital. Person-centred communication that takes into consideration the person and their family’s values has been shown to be important to clinicians, clients, and their families and improves quality of care and adherence (Kiran et al., Reference Kiran, Wells, Okrainec, Kennedy, Devotta and Mabaya2020). Research related to hospital-to-home transition interventions has found that good communication and collaboration improve quality of life and decrease readmission rates (Verhaegh et al., Reference Verhaegh, MacNeil-Vroomen, Eslami, Geerlings, de Rooij and Buurman2014). Hence, staff training about the importance of and the implementation of person-centred communication and collaboration with program participants to set goals should continue in any model of care.

Even though there are many policy and structural changes that would need to be implemented at a macro level, such as increased funding to expand the program and improve sustainability, and a health care deliver-wide communication system, there are changes that can be made at a micro level that would lead to program enhancement. Barriers such as lack of program knowledge and awareness, communication, referral processes. and eligibility criteria could be addressed through various initiatives. For example, pamphlets, a dedicated Web site, or orientation videos could be developed for new referring staff. Research has shown that a dedicated platform, such as a Web site with articles, program information, and printable forms and documents can serve as a centralized repository of resources for health care providers, referral staff, older adults, families, and the community and can improve awareness of services (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Escher, Mengle and Sullivan2018). Incorporating tools such as decision aids would improve experience of those using the service and lead to greater uptake of the service. For the model of care, an eligibility criterion check list, as well as the availability of referral and standardized assessment forms would be important to have for referring staff to improve their experience and improve uptake. Online and other tools would be a mechanism for seamless sharing of information across care delivery levels, would assist in reducing inappropriate referrals to the program, and could serve to highlight the successes of the program. Although these initiatives would not require policy changes, funding would be required for implementation.

The current program structure and constraints were considered barriers. The study participants felt that there should be more flexibility; for example, full days or half days, the ability to participate in the program for more than 30 days, and the ability to gradually taper attendance in the program. Older adults with complex health needs may require longer rehabilitation time to achieve independent living (Falvey, Mangione, & Stevens-Lapsley, Reference Falvey, Mangione and Stevens-Lapsley2015). A scoping review conducted by Maximos et al. (Reference Maximos, Seng-iad, Tang, Stratford and Dal Bello-Haas2019) that examined components of SSR programs in single-payer or single-payer-like health care systems worldwide found that the average length of SSR programs ranged from 2 to 4 months. Other types of community-based programs for older adults have ranged from 6 weeks to 3 months (Malik et al., Reference Malik, Virag, Fick, Hunter, Kaasalainen and Dal Bello-Haas2020). The desire to provide longer rehabilitation time or a step-down model to allow older adults to more gradually adjust to independent community living post-hospitalization is supported by literature and would be a unique feature of this program. However, providing this program flexibility would require increased funding allocation to support staffing and the capacity to accommodate the individualized program structure and the needs of other programs housed at the facility.

Limitations

Despite the richness of information gathered from this qualitative study, limitations exist. This study assessed one specific program in an LHIN in the province of Ontario; therefore, the extent to which findings about facilitators and barriers are generalizable to different settings, provinces, and countries is not known. With qualitative description methods, researchers developed themes without interpretation; therefore, an in-depth analysis of phenomena was not conducted. Qualitative description methodology does not often consider the intricacy and complexity of differing perspectives and multiple truths that often emerges in other qualitative methods such as phenomenology or ethnography studies. To ensure rigor and triangulation, as well as to ensure that themes resonated with multiple health professionals involved in the transition process, reflexive notes and themes were reviewed with a multidisciplinary research team during and post-analysis. However, themes were not revisited by study participants for confirmation, to decrease the demand on participants’ time and because of staff turnover. This meant that we did not have an opportunity to check interpretation of what was said during the interview process or to correct any misinterpretation or errors that may have occurred directly with the study participants.

Conclusion

This is one of the first studies to examine perceptions and perspectives of care providers working in or referring to a community-based, SSR, hospital-to-home transition program for older adults. Many positive aspects of the program, such as the services provided, the benefits to older adult clients, and person-centred communications would be vital to the program’s continued success, implementation, and functioning. Yet, many areas that were identified as barriers need to be addressed. Implementation of seamless patient information sharing through platforms or other tools, and the use of specific referral criteria and standardized outcome measures may reduce unsuitable referrals and inaccurate information, and may provide important information for referral and program staff. Future development and further expansion of existing programs should allow for individualized program design to suit the goals and needs of the older adult, but this would require changes at the macro level.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Mira Maximos for her assistance with this research.