Introduction and rationale

Conceptualizing mental health

According to the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA), mental health can be defined as our ‘positive sense of well-being, or the capacity to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face’ (Canadian Mental Health Association, Ontario, 2009, para. 1). The two-continuum model of mental illness and mental health indicates that mental illness and mental health, or mental well-being, are related but distinct dimensions (Keyes, Reference Keyes2002). It is possible to have a diagnosed mental illness and experience well-being, and it is also possible to experience poor mental health without a diagnosed mental illness. However, limited research has explored both mental illness and mental health simultaneously across the lifespan (Westerhof & Keyes, Reference Westerhof and Keyes2010). One recent study found that Dutch older adults experience less mental illness but do not have better overall mental health when compared to younger adults (Westerhof & Keyes, Reference Westerhof and Keyes2010).

Prioritizing the mental health of older adults

Age-related changes such as the loss of social roles, retirement, living alone, bereavement, and physical and mental health conditions can negatively impact overall mental health. Action to promote and support the mental health of older adults has been recognized as a priority both globally and at a national level in Canada. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Decade of Healthy Ageing incorporates a human rights approach that prioritizes the right to ‘enjoyment of the highest attainable standards of physical and mental health’ (World Health Organization, 2020, p. 7). This is expanded on in their Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan for 2013–2030, which included recommendations to ‘promote mental well-being, prevent mental disorders, provide care, enhance recovery, promote human rights and reduce the mortality, morbidity and disability for persons with mental disorders including in older adults’ (World Health Organization, 2021, p. 11). Recommendations encompass the need for: (1) effective leadership and governance for mental health; (2) integrated mental health and social care in the community; (3) strategies for promotion and prevention of mental health; and (4) strengthened information, evidence, and research for mental health (World Health Organization, 2021). Similarly, The Mental Health Commission of Canada released Guidelines for Comprehensive Mental Health Services for Older Adults in Canada in 2011, built around the principles of (1) respect and dignity; (2) self-determination; (3) independence; and (4) choice for consumers and aimed ‘to guide systems planners, government, policy makers, and program managers in planning, developing, and ensuring a comprehensive, integrated, principle-based and evidence-informed approach to meeting the mental health needs of seniors (MacCourt et al., Reference MacCourt, Wilson and Tourigny-Rivard2011, p. 14). This priority focus on older adult mental health is echoed in their 2019 report, which emphasizes that mental health is not a one-size-fits-all construct and instead requires an understanding of each person’s unique circumstances and context (Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2019).

Despite these evidence-based action plans and guidelines, there has been slow progress in advancing aging-focused mental health research, policy, and practice in Canada. The challenges and barriers associated with this slow progress can be summarized according to three evidence-informed themes: (1) pervasive societal misconceptions; (2) siloed and fragmented services and support; and (3) longstanding knowledge and evidence gaps.

Pervasive societal misconceptions

There are many misconceptions that affect general attitudes about aging and mental health. For example, dementia, more common among older adults than those who are younger, is often the focus for work on aging and/or mental health for older adults, but it is important to note that dementia itself is not a mental health illness. While older adults living with dementia can experience mental health issues, they can also experience mental well-being (Velayudhan et al., Reference Velayudhan, Aarsland and Ballard2020). Additionally, aging is often positioned as beginning at 65 years of age, and ageist perspectives can attribute older age as the cause of mental health concerns. From a social life course and biological perspective, aging begins from birth. Early and mid-life experiences can have a significant impact on mental health in later years (MacCourt et al., Reference MacCourt, Wilson and Tourigny-Rivard2011), and so addressing mental health in older adults can and should mean seeking resources throughout a person’s life. Further, there is stigma attached to both aging and mental health, which can prevent help-seeking for older adults with mental health needs (Herrick et al., Reference Herrick, Pearcey and Ross1997).

Siloed and fragmented services and support

Mental health is an essential part of overall health (Horgan & Prorok, Reference Horgan, Prorok, Ellis, Mullaly, Cassidy, Seitz and Checkland2022; Prince et al., Reference Prince, Patel, Saxena, Maj, Maselko, Phillips and Rahman2007). While this is becoming increasingly and more broadly recognized across Canada, there remains a lack of integration among the services and support meant to address physical and mental health needs, particularly for older adults with multiple co-morbidities (White et al., Reference White, Neal and McKenzie2017). As a result, older adults experiencing physical and mental health issues tend to have high rates of health service utilization, poor quality of life, and increased mortality (White et al., Reference White, Neal and McKenzie2017). Calls for increased interprofessional education and training opportunities for health and social care providers suggest that geriatric mental health, aging, and dementia care providers need more support to meet the needs of the aging population (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Luptak, Supiano, Pacala and De Lisser2018). Insufficient funding is a substantial factor in Canadians experiencing barriers to seeking mental health care. For example, a recent survey by the Angus Reid Institute found that almost 60% of Canadians who reported barriers in seeking mental health care had experienced barriers due to finances and/or high costs of services (Faber et al., Reference Faber, Osman and Williams2023). Older adults need equitable access to a full continuum of care and better linking of addictions, health, social services, housing, education, and the justice system services, including follow-up and wrap-around services that are culturally relevant (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2018). Current funding solutions are often too narrowly focused on reactive treatment and facility-based options, versus proactive, upstream preventative community-based supports (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2018).

Longstanding knowledge and evidence gaps

Major gaps in aging-focused mental health research have contributed to slow progress on making mental health support, care, and treatment options broadly available to older Canadians. Although concerns arising from the COVID-19 pandemic have spurred new recent funding opportunities, mental health research in Canada receives three times less funding than would be required to meet its morbidity burden (Woelbert et al., Reference Woelbert, White, Lundell-Smith, Grant and Kemmer2020). Mental health services research studies tend to be limited by small, non-representative samples and a narrow focus on the primary care sector (Callahan & Hendrie, Reference Callahan and Hendrie2010). Similarly, progress in biological aging and mental health research has lagged due to a lack of cross-discipline collaboration of scientists from biology, psychiatry, psychology, and epidemiology (Han et al., Reference Han, Verhoeven, Tyrka, Penninx, Wolkowitz, Månsson, Lindqvist, Boks, Révész and Mellon2019). There is also a need to extend knowledge, expertise, and methods for co-production, co-design, and other participatory research approaches for mental health research to ensure emerging evidence fully reflects and responds to diverse needs and experiences (King & Gillard, Reference King and Gillard2019).

Prioritizing aging and mental health

A joint recognition of the above challenges and barriers, and a mutual commitment to advancing the field of aging and mental health research led to a collaboration between the SE Research Centre and the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) National office in 2018. Together, and with input from key mental health experts and collaborators, including people with lived experience, they identified that it was important to work towards identifying a research agenda for aging and mental health in Canada. This included prioritizing the perspectives of older adults, their family and friend caregivers (hereafter referred to as caregivers) and health and social care providers. From these discussions, an overall objective was to identify the top 10 unanswered research questions on aging and mental health according to what matters most to Canadians within the context of support, care, and treatment.

Engaging with experts-by-experience to identify research priorities

Potential service users, caregivers, and clinicians all contribute valuable perspectives to the identification of future research initiatives. Previous research, mental health and otherwise, has demonstrated the priorities of these experts-by-experience can differ from those of academic researchers (Crowe et al., Reference Crowe, Fenton, Hall, Cowan and Chalmers2015; Ghisoni et al., Reference Ghisoni, Wilson, Morgan, Edwards, Simon, Langley, Rees, Wells, Tyson and Thomas2017; Tallon et al., Reference Tallon, Chard and Dieppe2000). As Chalmers et al. (Reference Chalmers, Bracken, Djulbegovic, Garattini, Grant, Gülmezoglu, Howells, Ioannidis and Oliver2014) note, research agendas set using a priority-setting partnership primarily include priorities related to education and training; service delivery; psychological interventions; physical interventions; exercise; and so forth, while published research disproportionately focuses on clinical interventions (e.g., pharmaceutical, surgical) (Telford & Faulkner, Reference Telford and Faulkner2004). In the context of mental health, experts-by-experience who prioritize a holistic understanding of mental well-being may be poorly represented by the traditional medical model ideology that often drives mental health research (Telford & Faulkner, Reference Telford and Faulkner2004). Research agendas that are developed in partnership with their target audiences/participants can also help to reduce instances of research ‘waste’ (e.g., projects with spurious conclusions, outputs that are neither relevant to advancing knowledge nor immediate application) (Chalmers et al., Reference Chalmers, Bracken, Djulbegovic, Garattini, Grant, Gülmezoglu, Howells, Ioannidis and Oliver2014; James Lind Alliance, 2021).

A note about COVID-19, aging and mental health

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated unmet mental health needs across Canada (Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 2020). Prior to the pandemic, 1.6 million Canadians reported unmet mental health care needs each year (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2018). A 2021 survey found that more than 60% of Canadians were experiencing worse mental health since the start of the pandemic, and while 11 million Canadians were experiencing high stress levels, only 1 in 5 had sought support for their issues (Thompson & Simpson, Reference Thompson and Simpson2021). A longitudinal analysis on the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of middle-aged and older adults revealed that this group was twice as likely to have depressive symptoms during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic, and subgroups with lower socioeconomic status and other poorer health factors experienced a greater impact (Raina et al., Reference Raina, Wolfson, Griffith, Kirkland, McMillan, Basta, Joshi, Oz, Sohel and Maimon2021). Loneliness was also found to be a significant predictor of worsening depressive symptoms in older Canadians (Raina et al., Reference Raina, Wolfson, Griffith, Kirkland, McMillan, Basta, Joshi, Oz, Sohel and Maimon2021).

Evidence of resilience in older adults through the pandemic has also been reported (Fuller & Huseth-Zosel, Reference Fuller and Huseth-Zosel2021), and compared to younger adults, older adults have been found to experience better psychosocial outcomes, even though they are more physically vulnerable to the virus (Minahan et al., Reference Minahan, Falzarano, Yazdani and Siedlecki2021). The range of emerging findings related to COVID-19, mental health, and aging reinforces the importance of learning more about the role and significance of age-related changes on mental health to better meet the diverse needs of people as they age and live in a post-pandemic future (Vahia et al., Reference Vahia, Jeste and Reynolds2020).

While the present study was designed prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, data collection took place during waves one and two of the pandemic. This means that the results of this study are reflective of lived experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic and are therefore relevant to informing post-pandemic planning for a more resilient and equitable health and social care system (Vahia et al., Reference Vahia, Jeste and Reynolds2020).

Methods

This project had three phases and was guided by an adapted James Lind Alliance (JLA) Approach to Priority Setting Partnerships (James Lind Alliance, 2021). See Figures 1 and 2 for a detailed breakdown of the study design. The JLA is a not-for-profit initiative supported by the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom (James Lind Alliance, 2021). The Priority Setting Partnerships (PSPs) approach was chosen as suitable to meet our objectives because it aims to meaningfully engage patients, caregivers, and health and social care providers in the development of shared research priorities through the following five-step process (James Lind Alliance, 2021):

-

1. Establish a steering committee

-

2. Invite partner organizations

-

3. Identify questions about aging and mental health

-

4. Process the data

-

5. Prioritize the questions

Figure 1. Modified priority setting partnerships project design.

Figure 2. Illustration of workshop flow.

JLA PSPs are typically guided by JLA Advisors, who are independent consultants and assist projects by acting as neutral facilitators throughout the process (James Lind Alliance, 2021). While hiring a JLA Advisor was outside of the budgetary scope of this community-led project, the study team applied expertise in participatory research and consultation methods to design an inclusive approach across all phases of the work.

This project was reviewed and received ethics exemption from the Southlake Regional Health Centre Research Ethics Board for Phase 1 & 2 (REB# 044-1920) and Phase 3 (REB# S-052-2021). In Canada, research studies are governed by the Tri-Council Policy Statement (at the time of exemption, this was TCPS 2 2018), which determines what does and does not require ethics review (Canadian Institutes of Health Research et al., 2018). The Southlake Regional Health Centre Research Ethics Board (REB) received the ethics packages in 2019 (Phase 1 and 2) and 2021 (Phase 3) and determined in both instances that the proposed activities fell outside of the scope of research subject to REB review as defined under article 2.5 of the TCPS 2 2018 whereby ‘quality assurance and quality improvement studies, program evaluation activities, and performance reviews, or testing within normal educational requirements’ (Canadian Institutes of Health Research et al., 2018, p. 18) do not require ethics approval and thus are ethics exempt. Given the variance in ethics governance structures across countries, ethics approval may be required outside of Canada for this type of priority-setting initiative. The findings are reported according to the REPRISE guidelines for priority-setting in health research (see Supplementary Material A) (Tong et al., Reference Tong, Synnot, Crowe, Hill, Matus, Scholes-Robertson, Oliver, Cowan, Nasser and Bhaumik2019).

Collaboration with experts-by-experience (JLA Steps 1, 2)

Together with the CMHA National office, the project team held a breakfast session at the 2019 Mental Health for All conference, which was, at the time, the largest community mental health gathering in Canada. The goal of the session was to explore how aging researchers and mental health researchers could come together to set an agenda for aging-focused mental health research in Canada. At this session, it was collectively decided by attendees that the direct input of aging Canadians, caregivers, and health and social care providers was needed to understand what research is most urgently required for changing the conversation about aging and mental health in Canada. A steering group of 13 experts-by-experience, including older adults, caregivers, and health and social care providers, as well as representatives from collaborating organizations (e.g., Mental Health Commission of Canada, Schlegel-University of Waterloo Research Institute for Aging, local CMHA branches) was formed following the breakfast session. Participant recruitment was based on follow-up with session attendees and a broad public online survey using SurveyMonkey. The steering group met monthly (n = 20) online for the duration of the project to guide all aspects of the PSP, using the Microsoft Teams platform for video and telephone dial-in. Steering group members contributed to the project in multiple ways, which included (but were not limited to): reviewing recruitment and data collection materials for clarity and appropriateness, sharing recruitment materials with their network, providing feedback on draft knowledge mobilization materials, and brainstorming how to pivot the project online at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. All steering group meetings started with introductions and a group reflection question to build rapport and sustainable working relationships. Members were sent an agenda and materials for review in advance of each meeting and asked to provide input and feedback to guide all aspects of the project. A project website (https://research.sehc.com/resources/aging-in-society/aging-mental-health-priorities) was developed and used to post up-to-date information about the project, with an open invitation for members of the public to get involved in the steering group.

Phase 1: Identifying questions about aging and mental health (JLA Steps 3, 4)

A national survey was conducted to identify Canadians’ broad questions and concerns about aging and mental health. The survey was developed in collaboration with the steering group and was organized into three sections to encourage participants to think about mental health holistically, including mental health support, care, and treatment defined as follows:

Support: information, resources and services meant to communicate to, educate, or connect people around mental health (e.g., CMHA website).

Care: services focused on protecting and promoting individual abilities and strengths of anyone experiencing poor mental health (e.g., counselling).

Treatment: medical and professional interventions to cure or alleviate symptoms of a diagnosed mental health illness (e.g., medication).

Each of the three sections was structured with a single open-ended text box, and the same question prompts as follows:

When you think about mental health (support/care/treatment) and aging:

What questions come to mind?

What topics do you want to know more about?

What type of support/care/treatment is most important to you?

The survey also included a brief section to collect information about participant characteristics, with questions about the perspective(s) they bring (e.g., older adult, caregiver, health, and social care provider), age, gender identity, race/ethnicity, and geographic location (see Supplementary Material B for a copy of Survey 1).

Data collection

The survey was made available online through SurveyMonkey and via paper copy. Inclusion criteria for survey participants were (1) that they had to be currently living in Canada, and (2) identify as one or more of the perspectives of an: older adult (age 55+); caregiver (family, friend, neighbor, and so forth, who provides support to an older adult); and/or health and social care provider (paid to provide care to older adults). Older adults were intentionally defined as ‘age 55+’ as a more inclusive guide for self-selection than the standard age requirement for senior citizenship in Canada (i.e., age 65+). A snowball sampling strategy was used to engage as many Canadians as possible, aligned with evidence for best sampling methods for research priority-setting with hard-to-reach communities (Valerio et al., Reference Valerio, Rodriguez, Winkler, Lopez, Dennison, Liang and Turner2016). The survey was promoted online through affiliated social media accounts and leveraging the personal and professional networks of steering group and project team members through email, posting the survey link to the dedicated project website, and promotional posters in local community sites (e.g., grocery stores). All recruitment materials and the survey itself were made available in English and French. The cover page of the survey included detailed information about the project, and participants had to check a box to provide informed consent. At the end of the survey, participants were given the opportunity to sign up for updates on the project or to indicate their interest in participating in a future stage. They were also given the option to enter a draw to win one of ten $50.00 CAD gift cards. Survey data collection took place between February 4, 2020, and June 9, 2020.

Data analysis

As there were no pre-defined criteria used to scope survey responses regarding their connection to the aging and mental health topic, all survey responses from participants who met the inclusion criteria were retained and exported into Microsoft Excel and de-identified for analysis. Quantitative analysis involved calculating descriptive statistics for the participant characteristics. Conventional qualitative content analysis was used to code the free-text, open-ended survey responses (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005). This analytical approach was chosen as it is appropriate for areas where existing research on the phenomenon is limited, in this case, Canadians’ questions about aging and mental health. Three team members (JG, KY, EK) coded the data so that all survey responses were coded individually by at least two people. After an initial round of open coding for each of the three sections, the respective two team members met to discuss the codes and categorize them into main codes (i.e., different mental health topics), and sub-codes (i.e., elements related to each mental health topic). The consensus coding framework was then applied to the remaining responses. After all the coding was complete, two members of the team (KY, EK) collaboratively consolidated the main codes and sub-codes into a representative set of questions about aging and mental health. Codes and sub-codes that were applied only once within the dataset were excluded. One researcher (JG) independently reviewed and revised the draft questions.

The Survey 1 questions were checked against existing evidence via a rapid scan of academic and grey literature published in the 10 years prior. The goal was to identify whether research attention had been given to any of the identified questions and to use this preliminary understanding as a focusing step to ensure the questions that would be moved forward into Phase 2 prioritization were those which had received the least amount of research attention to date. The list of questions was divided between team members JG, EK, PH, and KY who searched electronic databases (e.g., Medline/PubMed, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar) to identify peer-reviewed literature, focusing on review papers. Hand searching of the reference lists was also completed to identify additional literature. The titles and abstracts/ lay summaries of relevant papers were reviewed for key findings. Scanning the websites of relevant Canadian organizations (e.g., CMHA, Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health, Fountain of Health, the Mental Health Commission of Canada) led to the identification of grey literature sources. Information from white and grey literature sources was considered by the assigned member of the research team before categorizing a question as: (1) answered; (2) partially answered; or (3) unanswered by existing evidence. Questions were considered answered when peer-reviewed published literature was available to address all elements of a question. Partially answered questions were defined as either: (a) questions where some peer-reviewed literature existed but did not cover all elements of a question; or (b) where only grey literature existed. Questions were categorized as ‘unanswered’ where no peer-reviewed or grey literature could be found to address the elements of a question. After all team members completed their individual review of the literature against their assigned questions, a meeting was held to discuss and finalize the categorization of each question. Questions, categories, and evidence were then brought forward to the steering group for consensus. A decision was made with the steering group to drop questions categorized as answered for further prioritization, given the attention they had been given by existing research. Partially answered and unanswered questions were collapsed for further prioritization in Phase 2, given the team’s assessment of their collective need for additional research attention.

Phase 2: Interim prioritization of questions on aging and mental health (JLA step 5)

A second national survey was conducted to identify a short list of priority questions. Questions that were categorized as answered after the literature scan were excluded from the second survey. The survey included one main question, which asked participants to select up to 10 of the questions they felt were most important to answer through future research on aging and mental health. The second survey included the same participant characteristics section as the first survey, described above (see Supplementary Material C for a copy of Survey 2).

Data collection

Online administration of Survey 2 followed the same processes as Survey 1, including inclusion criteria, recruitment strategy, consent, and participant honoraria. Individuals who completed the first national survey and who (a) indicated they were interested in receiving updates about the project, or (b) wanted to participate in the next stage of the project, were contacted via email and invited to complete Survey 2. Data collection for Survey 2 took place between November 12, 2020, and January 4, 2021.

Data analysis

Survey responses were downloaded into Microsoft Excel and de-identified for analysis. Quantitative descriptive analyses were completed to generate the short list of questions that were advanced to Phase 3. To sort the list from overall ‘highest priority’ to overall ‘lowest priority’, a series of weighted endorsement scores were generated for each question (see Supplementary Material D for example calculations). Questions selected by participants were assigned a base value of 1.00, while unselected questions were assigned a base value of 0. To generate a weighted value based on the proportion of questions selected by a given participant (up to 10), the base value was divided by the number of questions picked. For example, if a participant picked 7 questions, the weighted value for each of those questions would be 0.14 (i.e., 1.00/7). A weighted sum score was produced for each of the unanswered questions by adding the weighted values for a question across participants.

Dividing by the total weighted number of responses and multiplying by 100 generated a weighted percentage of endorsement between 0% and 100%. Weighted percent of endorsements were also calculated based on the following participant characteristics: perspective, age, gender, geographic area, and ethnicity. Questions that were endorsed by at least 33.3% of two or more key underrepresented groups in survey research were included in the short list for Phase 3. For the purposes of this analysis, under-represented groups were defined as: adults 76 years of age and older, men, non-White individuals, and those who live outside of Ontario (Florisson et al., Reference Florisson, Aagesen, Bertelsen, Nielsen and Rosholm2021; Lam et al., Reference Lam, Simpson, John, Rodriguez, Bridgman-Packer, Cruz, O’Neill and Lewis-Fernández2022; Woodall et al., Reference Woodall, Morgan, Sloan and Howard2010).

Phase 3: Online workshops and nominal group technique (JLA step 5)

A nominal group technique was used to engage participants in quick decision-making in a way that both generates consensus on priorities and ensures individual opinions are heard and considered (James Lind Alliance, 2021). The nominal group technique involves both small and large group discussions and voting/ranking (James Lind Alliance, 2021). Typically, this is done through a single all-day in-person, face-to-face workshop, but due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions on travel and in-person gatherings, a series of four shorter online workshops were conducted instead.

Data collection

Inclusion criteria for workshop participation was consistent with Surveys 1 and 2. Workshop attendees were recruited using a stratified convenience sampling of previous survey participants across three waves. In wave 1, individuals who previously indicated in Survey 1 or 2 that they would be interested in receiving updates about the project and who were currently living outside of Ontario were first invited by email to participate in the workshops. This included individuals who self-identified as representing one or more of the underrepresented groups defined above. In wave 2, which was conducted one week after wave 1, individuals who represented one or more of the underrepresented groups and were living in Ontario were invited to participate by email. In wave 3, two weeks after wave 1, all other interested individuals were contacted. Reminder emails were sent to potential participants one week after their initial invitation email, for all waves except wave 3, which only received one email. The email invitation included a link to register for one of four pre-scheduled workshop dates and times. Efforts were made to provide a wide range of workshop timing options to facilitate participation from across the country. Each of the first three workshops was designed to focus on one of the three perspectives of interest (i.e., older adults, caregivers, health, and social care providers) and include 8–10 participants. The fourth workshop was designed to include all three perspectives of interest and include up to 30 participants. Once registered, prospective participants were contacted by EK for a pre-workshop introduction call to provide information about the project, overview the pre-workshop activity and the planned workshop agenda, and provide technological support to familiarize participants with the Microsoft Teams meeting software in advance of the session. A variety of options were given to participants to make workshop participation as user-friendly and feasible as possible, including dialing in for the workshop by phone, having a paper copy of the pre-workshop materials mailed to them, and receiving a reminder call or email one to two days before the workshop.

One to two weeks before the workshop, participants were emailed or mailed a pre-workshop activity and instructed to complete it prior to the workshop and have it with them at the session to inform their participation in the discussions. The pre-workshop activity included the short list of unanswered questions from Phase 2, and attendees were asked to select, based on their opinion, the top three most important and the bottom three least important questions for Canadians, with room to include a brief explanation for their choices.

The series of four workshops were held in April 2021 and were facilitated by project team members JG, EK, and PH. In the first three workshops, attendees first completed an introduction activity before JG discussed the purpose of the workshops and the project overall. Attendees were then asked in a roundtable fashion to share their top and bottom three rankings, which were captured live by JG on a spreadsheet which attendees could observe. PH lead and JG facilitated a discussion on the convergent and divergent rankings, with a goal to establish a consensus on the top 10 ranked-ordered questions. EK took detailed typed notes and provided technological support to attendees during the session. Attendees were shown a ranked list of the top 10 questions based on their scores and were given the opportunity to either omit or add questions back into the list for consideration if most of the attendees agreed. Consensus was decided through discussion and/or a majority vote in some cases.

The results from the first three workshops were shared in advance with the participants in the final fourth workshop, which was facilitated as three small working groups of mixed perspectives who again each did a prioritization and ranking process. Workshop participants were offered a $50.00 CAD e-gift card in appreciation for their time. See Figure 2 for a detailed flow chart of the workshop process.

Data analysis

The top 10 unanswered research questions on aging and mental health according to Canadian older adults, caregivers, and health and social care providers were generated using Microsoft Excel. The final rank-ordered list of the top 10 questions from each of workshops one, two, and three and each of the three working groups in workshop four were entered into a spreadsheet for comparison. For each of the six groups, a scored list was produced – numbers 1 through 10 represented the top 10 questions of the group. No groups chose to add any extra questions to their priority lists, and thus any remaining unranked questions were assigned a score of 11. A consensus list was produced by summing together the score for each question across the groups. The lowest scores represented questions that had been highly important to all groups.

In recognition of the unique challenges and opportunities for disseminating the research priorities during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the four workshops were transcribed verbatim and used to augment the existing notes taken by EK during the workshop.

Results

Phase 1: Identifying questions about aging and mental health (JLA Steps 3, 4)

Participant characteristics

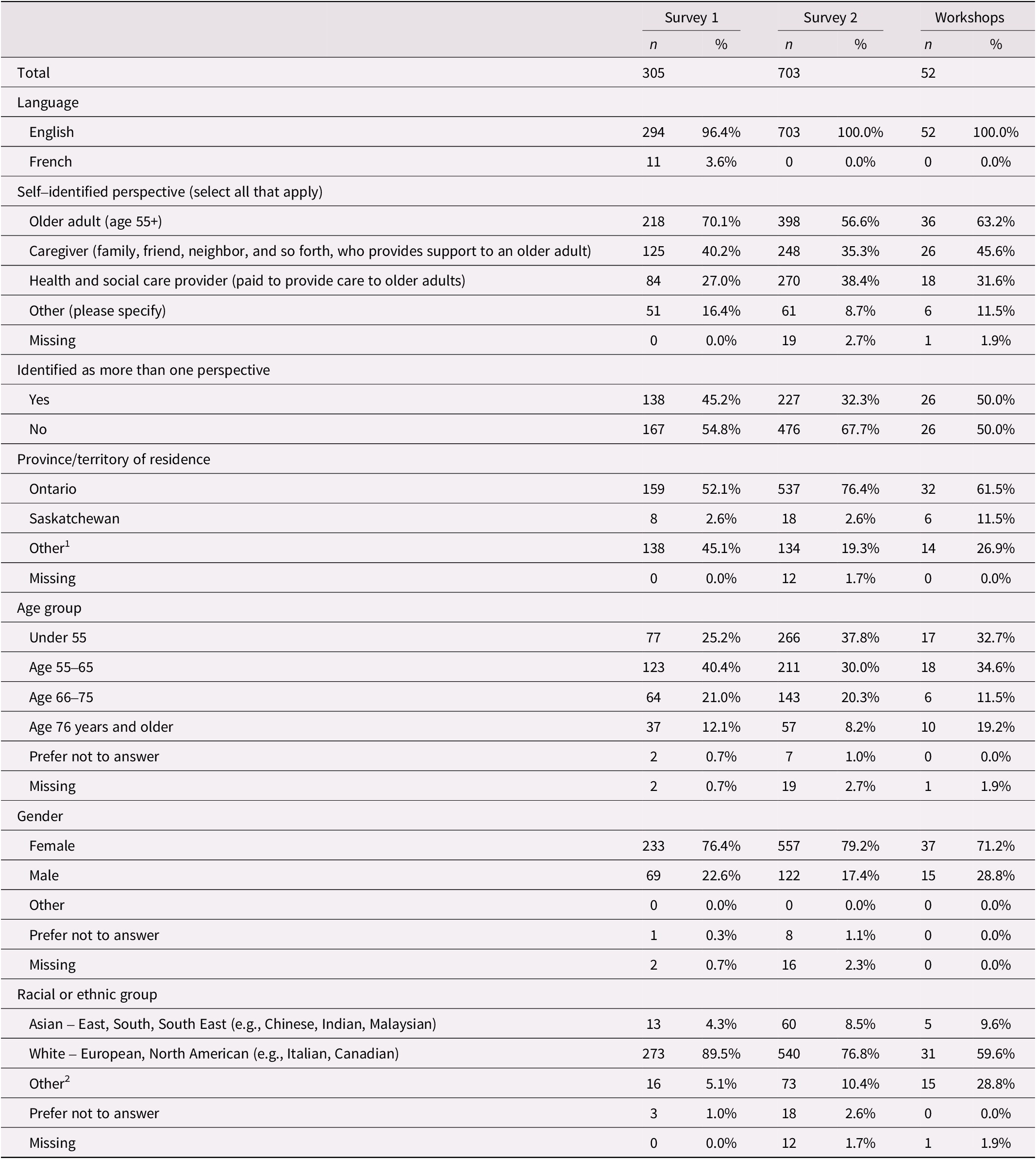

A total of n = 305 respondents completed Survey 1, with most respondents answering in English. Most identified as White (either European or North American) (see Table 1). Over 70% of respondents identified as an older adult, while just over 40% identified as a caregiver for an older adult, and approximately one-quarter identified as a health and social care provider. Almost half of the respondents identified as having more than one perspective. Respondents were primarily living in Ontario, although there was at least one respondent from 11 of the 13 provinces and territories in Canada.

Table 1. Participant characteristics across the pan-Canadian surveys and online workshops

1 ‘Other’ includes free text responses and any provinces/territories with less than five respondents. This includes Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nunavut, Nova Scotia, Northwest Territories, Prince Edward Island, Quebec, and Yukon.

2 ‘Other’ includes free text responses (e.g., Caribbean, not ‘black’; Indian – African (African with origin in India)) and any categories with less than five respondents. This includes Black – African (e.g., Ghanian), Black – Caribbean (e.g., Barbadian), Black – North American (e.g., Canadian), First Nations, Indigenous/First Nations – not included elsewhere, Métis, Indian – Caribbean (e.g., Guyanese with origins in India), Latin American (e.g., Argentinian), Middle Eastern (e.g., Egyptian), Mixed heritage (e.g., Black – African and White – North American), and do not know.

No respondents identified as Inuit.

Questions from Survey 1

Phase 1 survey responses were consolidated into a list of 42 unique questions on aging and mental health. Questions were phrased broadly to pertain to a variety of research areas (e.g., biomedical, clinical, health services and population health research) and/or types of research (e.g., prevention, diagnosis, treatment, health system and policy). Seventeen questions were categorized as answered, 17 as partially answered, and eight as unanswered. See Table 2 for a full breakdown of the questions and their categorization. All the questions, including those categorized as ‘answered’, are publicly available on the project website (https://research.sehc.com/resources/aging-in-society/aging-mental-health-priorities).

Table 2. List of 42 questions identified from respondents of Survey 1

Phase 2: Interim prioritization of questions on aging and mental health (JLA step 5)

Participant characteristics

A total of n = 703 respondents completed Survey 2, with all respondents answering in English. Respondents primarily identified as White (either European or North American) (see Table 1). Almost 57% of respondents identified as an older adult, while just over one third identified as a caregiver for an older adult, and almost 40% identified as a health and social care provider. About a third of the respondents identified as having more than one perspective. While respondents were predominantly living in Ontario, there was at least one respondent from 12 of the 13 provinces and territories in Canada.

Shortlisted questions from Survey 2

Survey 2 refined the list of 25 unanswered or partially answered questions to a shorter list of 18 questions, prioritizing questions most frequently selected as important by respondents overall and individuals in key under-represented groups (e.g., adults 76 years of age and older, men, non-White individuals, and those who live outside of Ontario). Table 3 illustrates the short-listed questions emerging from Survey 2.

Table 3. Short list of 18 unanswered questions prioritized by respondents of Survey 2

Phase 3: Online workshops and nominal group technique (JLA step 5)

Participant characteristics

A total of n = 52 participants, all speaking English, attended one of four workshops. Participants primarily identified as White (either European or North American) (see Table 1), with just under one-quarter of participants identifying as either South Asian, Black-African, or Métis. Just under 30% identified as male. Most participants identified as an older adult, while just under half identified as a caregiver and about one-third identified as a health and social care provider. A full half of the workshop participants identified as having more than one perspective. Respondents were predominantly living in Ontario. Approximately 30% of participants came from Saskatchewan, British Columbia, and Manitoba.

Top 10 unanswered research questions on aging and mental health

From the series of workshops, the final list of top 10 priority unanswered research questions was generated (see Table 4). The top unanswered question focused on building mental health-related skills in health care providers who are not mental health specialists. The second priority unanswered question asked about the type of supports that minimize the impacts of loneliness for those who are socially isolated. One question focused on access to care (#3), while another focused on person-centred care in mental health (#4). Technology was explored in question #5, and #6 looked at the mental health care needs of older adults during care transitions. One question (#7) focused on care provider burnout. Two questions focused on caregivers in the context of being involved in care planning (#8) and bolstering their own well-being (#10). One question (#9) highlighted financial supports and resources for older adults who cannot afford mental health care.

Table 4. List of the top 10 unanswered questions selected and ranked by workshop attendees

Discussion

The identification of aging and mental health related research priorities of aging Canadians is a novel contribution to the academic literature. Although other PSPs have identified mental health and mental health-related phenomena (e.g., psychological well-being, experiences of social isolation) as important priorities for older adults (Hanson et al., Reference Hanson, Cowan and Wagg2021; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Corner, Laing, Nestor, Craig, Collerton, Frith, Roberts, Sayer and Allan2019), the work described in this paper provides more tailored guidance for research and action to address the pervasive societal misconceptions; siloed and fragmented services and support; and longstanding knowledge and evidence gaps in the mental health landscape for aging Canadians.

In terms of societal misconceptions, the top priority research question uncovered in this work indicates that aging Canadians feel there is a need for more diffuse knowledge and skills across the health system workforce to attend to the unmet mental health care needs of this population. In a recent survey of nurses working in the United States, those with specialized mental health skills had comparatively lower levels of stigma than other nurses, with knowledge found to partially mediate the relationship between nursing specialty and stigma (Kolb et al., Reference Kolb, Liu and Jackman2023). This evidence supports the hypothesis that better equipping the health care workforce with skills to care for mental health-related needs may help to mitigate stigma associated with mental health.

In terms of siloed and fragmented services and support, the priority research questions are more likely to spark needed interdisciplinary collaborations to advance work on policy, program, and practice solutions to challenges associated with interactions between aging and mental health/illness (Cosco et al., Reference Cosco, Randa, Hopper, Wagner, Pickering and Best2022). A recent paper emphasized evidence for the interaction between physical, mental, social, and environmental experiences in creating a healthy aging process, substantiating the argument for mental health as an essential indicator of overall health (Horgan & Prorok, Reference Horgan, Prorok, Ellis, Mullaly, Cassidy, Seitz and Checkland2022). Providers may also find the priority research useful to their continuing professional development by suggesting areas for broadening expertise which may be especially meaningful to their clients and by providing justification to potential gatekeepers (e.g., managers) for why these topics are important (Cleary et al., Reference Cleary, Horsfall, O’Hara‐Aarons, Jackson and Hunt2011). For example, one of the priority questions indicates that aging Canadians recognize the need to better understand and attend to the mental health needs of older adults during care transitions. This question is supported by a recent qualitative study on experiences of older adults during the transition from hospital to home, which reported that providers have limited training on the mental health issues and needs of older adults, often focusing more on physical symptoms and concerns (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Qian, Liu, Wang, Zhuansun, Xu and Rosa2023). These findings suggest that future research to address this priority question could support the delivery of more integrated physical and mental health care.

In terms of longstanding knowledge and evidence gaps, the priority research questions are a valuable starting point for funders, researchers, organizations, and providers working in the area of aging and/or mental health in Canada (Staley et al., Reference Staley, Crowe, Crocker, Madden and Greenhalgh2020). This project serves as a positive example of involving experts-by-experience in decision-making, research, and action as it relates to their mental health support, care, and treatment (Telford & Faulkner, Reference Telford and Faulkner2004; Wykes et al., Reference Wykes, Bell, Carr, Coldham, Gilbody, Hotopf, Johnson, Kabir, Pinfold and Sweeney2021). There is an increasing recognition of the fundamental democratic right of all individuals, including older adults, caregivers, and care providers, to participate in the development, completion, and mobilization of research that concerns them (Telford & Faulkner, Reference Telford and Faulkner2004). Intentional commitment is needed from researchers to consistently uphold this right to address pervasive epistemic discrimination in science (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Cameron, Casey, Beresford and McLaughlin2022). Other benefits of participatory versus non-participatory research methods include higher quality data and analysis; outputs that are more appropriate and relevant; and projects that are more fundable (Ghisoni et al., Reference Ghisoni, Wilson, Morgan, Edwards, Simon, Langley, Rees, Wells, Tyson and Thomas2017). The inclusion of experts-by-experience in research and action also supports implementation of evidence at scale (Wykes et al., Reference Wykes, Bell, Carr, Coldham, Gilbody, Hotopf, Johnson, Kabir, Pinfold and Sweeney2021). Research based on priorities identified by experts-by-experience appears more likely to attract their continued involvement (Ghisoni et al., Reference Ghisoni, Wilson, Morgan, Edwards, Simon, Langley, Rees, Wells, Tyson and Thomas2017). Funders play a critical role in the reduction of research waste, and integrating these priorities into future grant/ program opportunities can help guide the development of outputs that are relevant, appropriate, and efficient (Chalmers et al., Reference Chalmers, Bracken, Djulbegovic, Garattini, Grant, Gülmezoglu, Howells, Ioannidis and Oliver2014; Staley et al., Reference Staley, Crowe, Crocker, Madden and Greenhalgh2020).

Strengths and limitations

There are several strengths present in this work. First, we formed a steering group of experts-by-experience at the outset of the project who provided insight and support in all aspects of the work. Engaging experts-by-experience not only in the priority-setting process but in the development, management, and actioning of the work helped ensure we stayed true to our commitment to authentic partnerships. Steering group members were able to speak candidly and openly about their feedback to the project team, which enhanced the quality and appropriateness of the work completed. For example, steering group members reviewed and provided feedback on the wording of the Survey 1 questions to improve their relevance and understandability. The steering group has continued its commitment to advancing aging and mental health in Canada and the group has since been formalized into the Canadian Aging Action, Research, and Education (CAARE) for Mental Health Group. The CAARE Group is building on the priority questions, with three goals: (1) to build authentic partnerships that advance aging and mental health support, care, and treatment in Canada; (2) to support research- and action-oriented projects on the priority unanswered and answered questions; and (3) to secure funding to support the priorities and activities of the group.

A second strength is that, with the support of the steering group, the project was successfully transitioned online at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Transitioning online enabled us to host four workshops with individuals from across Canada, which would otherwise not have been possible given logistical and budgetary constraints. In turn, being able to open the workshops to attendees from across Canada greatly increased the diversity of perspectives that were sampled. Additionally, practices that were trialed during the online transition (e.g., arranging proactive support for individuals to participate in an online format) have since been integrated in multiple projects led by the SE Research Centre. These practices have helped ensure the successful engagement of workshop attendees, even at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

One limitation to consider when interpreting the findings from this work is that the diversity of participants included is not representative of the total aging populace in Canada, despite efforts during recruitment to reach as many Canadians as possible. As such, priority questions should be re-confirmed as relevant to the individual contexts in which they are applied in partnership with experts-by-experience. Since this project, the SE Research Centre has made efforts to increase our equitable inclusion of individuals who are more representative of Canada’s diverse population in follow-up research stemming from this work. This includes intentionally partnering with French-speaking organizations, recruiting more diverse members for project working groups, and engaging with co-investigators in other provinces to better secure a non-Ontarian perspective.

Next steps

In line with recommendations from research examining the long-term uptake of PSP outputs (Staley et al., Reference Staley, Crowe, Crocker, Madden and Greenhalgh2020), we are committed to building generative relationships with researchers, funders, and experts-by-experience to continue mobilizing knowledge of the priority questions and facilitating their uptake across health and social care sectors in Canada. As such, we will continue to work with the CAARE for Mental Health Group, which has, at the date of this writing, grown to 22 individuals, including older adults, caregivers, and health and social care providers who are committed to action on the top 10 unanswered questions and answered questions. Additionally, we have undertaken a research and action project funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research focused on addressing the top unanswered and answered research questions by co-designing an evidence-based approach to starting mental health conversations between older adults and health and social care providers during existing care interactions in home and community care contexts. A protocol paper on the multi-phase project has recently been published (Giosa et al., Reference Giosa, Kalles, McAiney, Oelke, Aubrecht, McNeil, Habib Perez and Holyoke2024).

Conclusion

The top 10 unanswered research questions on aging and mental health according to Canadians will help prioritize an aging-focused mental health research agenda and promote better collaboration across siloed care and research fields. Future research and action projects should incorporate one or more of the priority questions with authentic partnership from experts-by-experience to meaningfully advance mental health support, care, and treatment in Canada.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S071498082400028X.