The phrase “a picture is worth a thousand words” is not a cliché in politics. The picture superiority effect suggests that a single photograph communicates a significant amount of political information to voters and potentially influences their electoral decisions (Rosenberg et al., Reference Rosenberg, Bohan, McCafferty and Harris1986). Given this persuasive potential, political actors must make strategic choices about self-presentation—the information they provide to citizens about themselves (Fridkin and Kenney, Reference Fridkin and Kenney2014). Self-presentation is a form of communicative agency (Wagner and Everitt, Reference Wagner, Everitt, Wagner and Everitt2019). Political actors employ professional staff to craft appealing visuals that seek to construct, maintain or reinforce a positive public image. Research on Canadian prime ministers, for instance, shows that they use online political photography to demonstrate strong leadership qualities and to enhance their brand (Marland, Reference Marland2012; Lalancette and Raynauld, Reference Lalancette and Raynauld2019). In this research note, we take the visual self-presentation of Canadian politicians in a slightly different direction by applying a gendered perspective. That is, we consider that how politicians present themselves may include a response to the gender-based stereotypes held by citizens and the media (Dittmar, Reference Dittmar2010; Winfrey and Schnoebelen, Reference Winfrey and Schnoebelen2019). More specifically, we explore gendered self-presentation in the political photography posted on the Twitter feeds of party leaders in the 2018 Ontario election.

Schill (Reference Schill2012: 119) notes that visuals “remain one of the least studied and the least understood areas” of political communication research. This is especially true for digital technologies (Lalancette and Raynauld, Reference Lalancette and Raynauld2019). Even though the ability to post photos in tweets has existed since 2011, most studies on the use of Twitter for campaigning focus on the text of posts (Jungherr, Reference Jungherr2016). By focusing on gendered self-presentation in photos, we not only contribute to the visual political communication literature but also extend what is known about political uses of Twitter. Our main contribution is methodological. To our best understanding, there is little work on gendered self-presentation that focuses solely on visual content. Previous analyses tend to focus on visuals in conjunction with words (audio or written), such as television advertising or websites.

This research note is organized as follows: First, we situate this analysis in the self-presentation strand of the gendered political communication literature; we provide a theoretical overview before moving on to a review of the very small empirical research on gendered self-presentation online. Next, our methodological framework is presented, which is novel in two ways: it allows for the assessment of gender-based strategies in visual only content, and it moves beyond parental status as the main variable of assessment. Then we test the utility of the framework using the photos posted on Twitter by the three leaders during the 2018 Ontario election.Footnote 1 The 2018 Ontario election presents an interesting test case because of the diversity of leaders. Despite a record number of women party leaders in provincial and federal politics around 2013 (Trimble et al., Reference Trimble, Tremblay, Arscott, Trimble, Tremblay and Arscott2013), there were only five at the time of analysis, two of whom were in Ontario and one of whom is openly gay.Footnote 2 The final section reflects on the methodological challenges of examining gender in visual political content online.

Gendered Political Communication

A starting premise of gendered political communication literature is that people tend to hold expectations or beliefs about what is appropriate for men and for women (Fridkin and Kenney, Reference Fridkin and Kenney2014). Gender expectations include descriptive and prescriptive norms; there are expectations about how women and men do behave and how women and men ought to behave (Winfrey and Schnoebelen, Reference Winfrey and Schnoebelen2019). Men are seen to possess agentic characteristics, such as being assertive, ambitious, confident and forceful, while women are seen to have communal traits, which are ascribed to traditional roles as caretakers (for example, affectionate, sympathetic, nurturing). Agentic traits are associated with strong and effective political leadership. Indeed, motherhood may be especially incompatible with politics (Thomas and Bittner, Reference Thomas, Bittner, Thomas and Bittner2017). Consequently, women politicians face challenges based on these descriptive and prescriptive norms. Women are not considered strong leaders because they do not possess agentic traits. At the same time, if a woman does exhibit agentic traits, she is seen to be violating prescriptive norms about how women ought to behave. This set of challenges is known as the “double bind” (Jamieson, Reference Jamieson1995).

There are three main strands in the gendered political communication literature (Wagner and Everitt, Reference Wagner, Everitt, Wagner and Everitt2019). The first strand of research explores how the news media cover female and male politicians. Citizen perception is the focus of the second strand. The final strand, and where this analysis fits, focuses on self-presentation by politicians. Here scholars consider the extent to which politicians employ notions of gender in constructing their own public image. While it is beyond the scope of this analysis to review the first two strands,Footnote 3 Canadian research shows that media frame politicians using gender stereotypes (see, for example, Gidengil and Everitt, Reference Gidengil and Everitt1999; Goodyear-Grant, Reference Goodyear-Grant2013) and voters evaluate them using those same stereotypes (see, for example, Everitt et al., Reference Everitt, Best and Gaudet2016; Lemarier-Saulnier and Giasson, Reference Lemarier-Saulnier, Giasson, Wagner and Everitt2019). The conclusions of the first two strands lend practical importance to the self-presentation of politicians. Since the media frame politicians in stereotypical terms and voters evaluate them using those same stereotypes, it follows that how politicians present themselves to the public matters. Whether presenting themselves through televised advertisement, website or social media feed, politicians need to make strategic decisions about their message and image. Due to the double bind, these strategic decisions in self-presentation may be even more crucial for women politicians (Bystrom, Reference Bystrom, Holtz-Bacha and Just2017). Work by Bauer and Carpinella (Reference Bauer and Carpinella2018) suggests that how candidates present themselves visually matters. Using a survey experiment design, they find that the use of masculine visuals can negatively affect evaluations of female candidates.

Researchers have theorized about how politicians manage their self-presentation in light of gendered norms and expectations. In their analysis of US senators, Fridkin and Kenney (Reference Fridkin and Kenney2014) propose the strategic stereotype theory, which suggests that (1) politicians, both female and male, will consider gender stereotypes in their self-presentation and (2) they will attempt to capitalize on favourable stereotypes while downplaying damaging ones. Similarly, Schneider (Reference Schneider2014a, Reference Schneider2014b) suggests that politicians can employ one of three strategies. The first strategy is to reinforce stereotypes in order to benefit from existing voter expectations and norms. For example, female candidates will focus on issues such as education and poverty, as they convey communal traits, whereas their male counterparts will focus on economy and security. A bending or overturning stereotype is the alternative strategy. Candidates seek to “deviate from the status quo of the typical issue ownership or gender-reinforcing strategy” (Schneider, Reference Schneider2014b: 57). Here the political messages of a female candidate would focus on the economy, while a male candidate would include images of his family and private life. While reinforcing and bending are the two main strategies, candidates may also opt for a third: a mixed strategy, which emphasizes both feminine and masculine traits. Our analysis draws on Schneider's analytical frameworks in the development of the methodology.

Online Gendered Self-Presentation

While gender-based self-presentation has been explored in other media (Carpinella and Bauer Reference Carpinella and Bauer2019), scholars have also begun to explore gender-based self-presentation specifically in online environments, such as websites and social media. We situate our analysis in the latter literature, which has been largely focused on text-based communications on websites or social media (see, for example, Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Gainous and Holman2017). Some studies (for example, Evans and Clark, Reference Evans and Clark2016) find that gender differences exist online, while others (for example, Cook, Reference Cook2016) contend such differences are exaggerated. Only a modicum of research focuses on visual communication, and much of this uses parental status (for example, the presence of children in photos) as the measure for gender-based stereotypes.

Two studies exploring parental status on US congressional websites found that fathers tended to include their families in photographs, while mothers were more likely to de-emphasize their children online (Stalsburg and Kleinberg, Reference Stalsburg and Kleinberg2016; Meeks, Reference Meeks2016). The results of these studies suggest that the visual presence of children evoke different feelings and associations among voters depending on whether male and female politicians are involved. For male politicians, photos of children are received positively and tend to soften the agentic characteristics they are assumed to possess. Conversely, for female politicians, photos of children negatively accentuate communal traits and bring forth concerns about their work–life balance. Similarly, Lee's (Reference Lee2013) study of midwestern politicians in 2011 found that congresswomen employed traditionally masculine language and published visuals that emphasized their professional lives on their webpages. In this way, children and the presentation of the private sphere (stereotypically feminine visuals) can be generally viewed as assets to male politicians and as liabilities to female politicians. Outside of the US, Ross and colleagues (Reference Ross, Bürger and Jansen2018) found that male politicians tended to use familial visuals on Twitter more than female candidates during the 2015 British election. In another parental status study examining both text and visuals on the websites of Canadian Members of Parliament (MPs), the author found that female MPs were more reluctant to display photos of their children and rarely disclosed their parental status on their websites (Thomas and Lambert, Reference Thomas, Lambert, Thomas and Bittner2017). Beyond parental status, Chen and Chang (Reference Chen and Chang2019) analyze textual and visual self-presentation on Facebook and LINE (an Asian social messaging app) during the 2016 Taiwanese presidential election. Their research shows that the female candidate emphasized policy but also used emotional imagery. By contrast, the male candidate more frequently emphasized character issues and further softened these messages with emotional imagery.

While there are only a handful of studies that focus on visual self-presentation rather than text, all find significant gender differences in the photos displayed online. This suggests that both male and female politicians are overturning stereotypes when it comes to posting pictures of one's children. Perhaps there is something about visual political communication that allows for a greater ability to overturn gender stereotypes. However, most of these studies use parental status as the only measure of gendered self-presentation. Our method, outlined next, makes use of a wider variety of measures.

Method

Content analysis is the main methodological technique used in research on online gendered self-presentation and in studies on the political uses of Twitter. Content analysis is a means for “measuring or quantifying dimensions of the content of messages,” as it can depict and draw inferences “about the sources who produced those messages” (Benoit, Reference Benoit, Bucy and Lance Holbert2011: 268–69). It is “recognized as a powerful and valuable research technique for making objective, systematic, and usually quantitative descriptions of communication content” (Bystrom et al., Reference Bystrom, Banwart, Kaid and Robertson2004: 24). This research note is “supply digital research,” which focuses on the outputs from political actors and institutions on digital technologies (Small and Jansen, Reference Small, Jansen, Small and Jansen2020). It does not focus on uses of those outputs by audiences (demand research) and therefore does not make statements about citizen perception of gendered visual content (for instance, Bauer and Carpinella, Reference Bauer and Carpinella2018).

The starting place for our coding scheme is the broader visual self-presentation literature that is not necessarily gendered focused. This literature explores variables such as the presence/absence of the politician in visuals, formal or informal campaign settings, patriotic symbols, attire, facial expression, and presence of others in video or photos (see Mattan, Reference Mattan2018). We then draw on Schneider's (Reference Schneider2014a, Reference Schneider2014b) framework of reinforcing or overturning gender stereotypes. While a gender-based lens can easily apply to some of the variables in the broader literature, it applies less so to others. For instance, as seen above, a strategic decision to post photos that include or exclude a politician's family in photos would reinforce or deviate from gender stereotypes. However, it is less clear how an informal campaign setting, such as a picture of a candidate jogging, portrays a gender stereotype; therefore the coding scheme includes only those visual cues that have some empirical support of depicting a stereotypically feminine or masculine form of self-presentation.Footnote 4

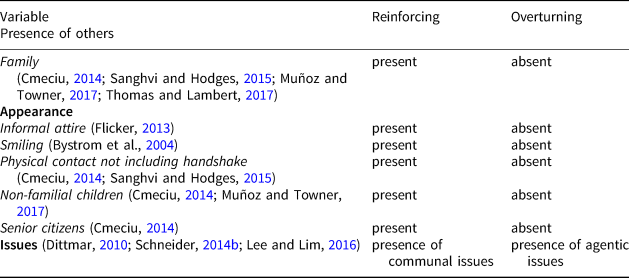

Table 1 presents the variables used in this analysis and their related literature. Moving beyond the variable of parental status, this framework explores a wide range of variables that are organized into three broad categories: presence of others, appearance and issues. Each variable is connected to a gender-reinforcing strategy from the perspective of a female political actor (the converse being true for male politicians). For example, in considering a leader's attire, a gender-reinforcing strategy would see a female leader wearing casual attire, such as a cardigan, whereas a male leader would be shown in more formal attire, such as a business suit. The variables are described in the results section. Each photo is assessed, dichotomously, for the presence or absence of the variable. In the case of presence of other actors, we coded only for those visual cues that exist in the foreground of the photograph; background actors are excluded. As our methodological approach is limited to variables of visual cues that had empirical support in the literature, it means the coding scheme may miss some gender norms that exist despite being more theoretically grounded.

Table 1 Visual Cue Variables for a Female Politician

It is important to clarify what we mean by gendered self-presentation in this study. We are not suggesting that politicians, in the moment, are choosing to reinforce or overturn gender stereotypes. Rather, campaigns “actively engage in visual framing strategies to promote desired candidate qualities and favored themes and to reinforce policy positions” (Grabe and Bucy, Reference Grabe and Bucy2009: 5). A campaign team will consider visual framing strategies prior to a campaign event when making logistical decisions (for example, location, attendees, clothing choices) and also after the event when a photo is selected to be posted on social media. As Marland (Reference Marland2012) points out, photo posting is a form of direct political marketing that communicates an unmediated message to voters. For Wagner and Everitt (2019: 11), a politician cannot “establish their preferred political femininity or masculinity through words alone. They must continually enact these beliefs through communicative actions that range from personal behaviours,” including “publicized interactions with family and friends to political activities such as staging photo opportunities, visiting specific locations, and meeting selected voters.” Given what we know about gendered mediation, we see the posting of campaign photos on Twitter as a form of communicative action where strategic choices regarding gender may be evident; that is, a photo may present a politician visually in a way that conforms or deviates from voter and media expectations as part of a politician's broader image-management strategy. The objective of our methodology is to assess this.

We use the 2018 Ontario election as a case study. Given the current lack of female party leaders in Canada, the diversity that existed in 2018 was a prime opportunity for analysis.

All tweets sent during the writ period, from the Twitter accounts of Doug Ford (@fordnation), Andrea Horwath (@AndreaHorwath) and Kathleen Wynne (@Kathleen_Wynne) were collected using the Twitter aggregator Twitonomy. Unlike previous studies, which focus on numerous candidates or legislators, we focus on party leaders. We do so for two reasons. First, party leaders are considered “the superstars of Canadian politics” (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jenson, LeDuc and Pammett1991: 89). They are the focal point of election campaigning in Canada, and research shows that leader evaluations are a significant determinant of voting preference (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Nevitte, Blais, Everitt and Fournier2012). Second, the Twitter accounts of leaders are far more popular than the accounts of the parties they represent or of local candidates (Small, Reference Small and MacIvor2010).Footnote 5 In Canada, leader feeds are the main way that the public follows partisan politics on Twitter. Our decision to focus on three leaders limits our analysis to descriptive statistics. However, the method developed would be applicable to analyses of any number of politicians.

The unit of analysis is a photo attached to a tweet posted directly from a leader's Twitter account. All other non-photographic tweets—such as text-based or video-based—are omitted from the corpus, as are profile photos, banner photos and retweets. Figure 1 provides an example. The three leaders tweeted a total of 739 times over the 29-day campaign. Of those, 333 included at least one photo, accounting for 431 photos in total. In instances where a tweet had multiple photos, each photo is considered a separate case. Given the fact that 45 per cent of leader tweets included a photo should draw attention to the importance of visuals on Twitter more broadly. The photos were coded by the researchers. We attained a good level of intercoder reliability, which measures the extent to which independent coders make the same coding decisions.Footnote 6

Figure 1 Example of Photo Attached to a Tweet

Results

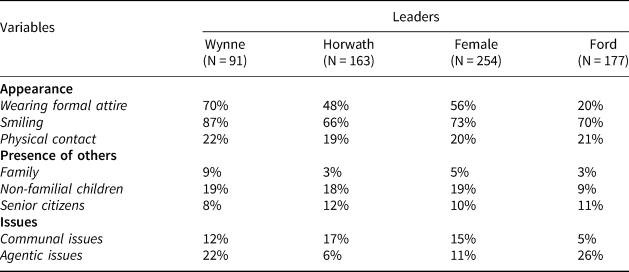

The presence of others is one indicator of gender-based stereotypes found in the literature. In addition to parental status, we look for the presence of seniors or other non-familial children. Consistent with communal traits that are often associated with caregiving, female leaders pictured with family members, children and/or seniors would represent gender-reinforcing strategy (Sanghvi and Hodges, Reference Sanghvi and Hodges2015). Despite these gendered expectations, we find the three accounts rarely posted pictures with these actors (only 29% included at least one of these actors). That said, the two female leaders were 48 per cent more likely than Ford to post a photo that included one of these others. This is particularly the case for children, as they appeared with Wynne in nearly a fifth of posted photos, as opposed to just under one in ten in Ford's feed. This suggests gender-reinforcing strategies for all three candidates. Differences can also be noted between the two female leader accounts. Wynne's feed was the most likely to include photos with her family (9%) and the least likely to be pictured with seniors (8%). Her feed included photos of her with her mother, daughter and granddaughter, partaking in a number of private activities, such as celebrating a special occasion, baking or taking a walk through the park. Conversely, the Horwath feed was the least likely to include photos of her family (3%) and the most likely to appear with senior citizens (12%). To be sure, presence of others is limited overall. That said, we do find evidence of reinforcing behaviours in the political photography on the Twitter feeds of all three leaders. Ford could have capitalized on the use of his family in photos, as we saw with several of the other parental status studies. Since male politicians do not face the double bind, they can present themselves as agentic but also nurturing and empathetic (McGregor et al., Reference McGregor, Lawrence and Cardona2017).

The next set of variables relate to appearance. Choices about physical appearance are not only crucial to self-presentation but are also gendered. Sanghvi and Hodges (Reference Sanghvi and Hodges2015: 1676–77) note the “notion of appearance is particularly salient for female politicians who . . . often face biased media coverage and receive greater attention to their physical appearance, including clothing, hair, and shoes.” In terms of clothing choices, there are some gendered differences in our data. The Wynne account typically posted photographs of her campaigning in informal clothing, including, blouses, sleeveless dresses and shirts (photo 1 of Figure 2): 70 per cent of all photos. Doug Ford, on the other hand, more often than not was pictured in formal attire, such as the blue suit jacket in photo 2 of Figure 2. This result is consistent with Marland's (Reference Marland2012) analysis of the online political photography of Stephen Harper, which determined that business jackets and suits were preferred by Harper. Photos in informal dress on the Ford feed were less frequent (20%) and typically occurred at special campaign locations, such as a construction site or when he was playing hockey with some children. Both of these findings are consistent with reinforced gendered norms, with formal attire being more likely associated with men than women. A far more mixed strategy was presented on the Horwath feed, which showed the politician in formal attire in 56 per cent of photos, while at other times, she sported informal cardigans.

Figure 2 Examples of Commonly Used Gender-based Strategies

Smiling and touching are considered more feminine qualities. Smiling is associated with women's desire to seek approval (Bystrom et al., Reference Bystrom, Banwart, Kaid and Robertson2004), while Cmeciu (Reference Cmeciu, Bakó, Horváth and Biró-Kaszás2014) suggests that the presence of physical contact (hugging and embracing) can be associated with women being perceived as compassionate. The three leaders are often smiling in the photographs posted to their Twitter feeds (74% of all photos), but they are seen engaging in physical contact in only around one of five photos. Consistent with gender reinforcement, there are more posts of the two female leaders smiling than Ford. That said, the Ford account also posts pictures with a smile on his face, which would be interpreted as overturning male gender norms. The opposite is the case for physical contact. By rarely showing photos of the politicians’ embracing or hugging, the feeds of Wynne and Horwath tended to deviate from compassionate gender norms. The lack of physical contact in the Ford feed is consistent with male gender expectations.

Finally, in terms of issue analysis, we draw on the work of Dolan (Reference Dolan2005). Looking at website text, she argues that when women politicians present themselves in a gender-reinforcing manner, they will emphasize communal issues, while men will highlight different, agentic issues. Communal issues include education, health care, seniors, addiction, food insecurity, environmental protection, and women's health and reproductive rights; agentic issues include the economy, military, security, law enforcement, defence, business and international affairs. The communal and agentic issue variables in Table 2 are the aggregation of any photo that features any associated issue. Photo 1 of Figure 2 features Wynne interacting with a newborn child at the Hospital for Sick Children; this would be a proxy for health care. In contrast, photo 2 shows Ford interacting with a veteran; this would be a proxy for military.

Table 2 Gender-based Visual Strategy by Candidate in Twitter Photos

Overall, there are 122 photos that feature a communal or agentic issue (28% of the entire sample). When presenting an issue, the Ford account more often presented agentic issues such as the economy and criminal justice. Only 15 per cent of all issues presented in his feed were coded as communal. More than three-quarters of the issues presented on the Horwath account were communal, such as her meeting with nurses at a hospital. Similar gender-based divisions were found in Lee and Lim's (Reference Lee and Lim2016) textual study of Clinton and Trump on Twitter. In fact, Clinton was more than eight times more likely to mention stereotypically feminine issues, such as women's rights, healthcare and education, on her feed when compared to Trump. Interestingly, the political photography on the Wynne account included more agentic issues (65% of all issue photos).

Our methodology, which moved beyond parental status, enabled us to see gender-related trends on Twitter for the three leaders. Overall, a gender-reinforcement strategy was more evident in the photos posted—this was particularly the case for the photos posted on Kathleen Wynne and Doug Ford's Twitter feeds: photos posted of Wynne included more stereotypically feminine traits, while photos posted of Ford included more stereotypically masculine traits. On the other hand, photos posted of Andrea Horwath were more mixed.

Discussion

The self-presentation and branding of political leaders has been gaining attention in Canadian political science. The picture superiority effect suggests visuals matter to politics. As such, understanding how campaign teams attempt to present politicians to others matters because this is an environment that is controlled by politicians and their staffs. Twitter, in general, and visual photography, more specifically, serve a number of purposes during an election campaign. Strategies on gender would be one of many considerations that the three leaders and their campaign teams would take into consideration. However, our methodology did allow us to reflect on gender in digital political photography. Our findings suggest that the social media teams of the three Ontario leaders used gender-based strategies in their political photography on Twitter. While evidence of reinforcement primarily appears in the feeds of Wynne and Ford, Horwath's team viewed a more mixed strategy as most beneficial to her gendered self-presentation.

We would be remiss to not highlight that our findings are complicated by party politics in Ontario. According to Ipsos (Bricker, Reference Bricker2018), the top campaign issues in the 2018 provincial election were healthcare (54%), the economy (36%), taxes (29%) and energy costs (28%); the latter three would be considered agentic issues. Ford's Progressive Conservative party sits more to the right of the ideological spectrum; thus the issues that are considered agentic are also ones associated with conservative parties more broadly. The same could be said for Andrea Horwath; communal issues such as health care and education are the raison d’être of social democratic parties such as the New Democratic party (NDP). Wynne is certainly a more interesting case. As a more centrist party, the Liberal party has a bit more flexibility to move from right to left as needed. Indeed, the term brokerage is often applied to Liberal parties in Canada; brokerage parties are characterized by flexibility in policy positions and ideological stance (Brodie and Jenson, Reference Brodie, Jenson, Gagnon and Tanguay2007). While issues on Wynne's account are more agentic than communal, this balance of issues could reflect the fact that she was the sitting premier. This observation is not necessarily a limitation of our method but of this particular case study, where gender and party overlap. To test this relationship more fully, analysis of a male party leader of the NDP, such as British Columbia's John Horgan, or a female leader of a right-wing party (which currently does not exist) would be useful. Alternatively, a larger data set of politicians (for example, MPs or candidates) would allow for the controlling of factors such as ideology.

Our primary contribution is methodological. There are very few analyses on gendered self-presentation that only focus on online visual content with little to no reference to text. Our analysis differs from previous work in that it moves beyond parental status and focuses on visuals in Twitter. As such, we make a unique empirical contribution to the digital politics and gendered political communications literatures. However, there are some limitations to the approach taken here. First, translating what is considered gendered from a text environment to a visual one proved challenging. Table 1 serves as a reminder that we only looked at a small number of variables of gender—ones that found theoretical support in the literature; this is a very conservative measure of gender-based stereotypes. It is probable that we missed photos that showed leaders engaging in what a layperson might see as gender-reinforcing or overturning behaviours. Future work may want to theorize more broadly on possible variables. Related was the issue of determining what was evidence of a lot or a little of either form of presentation. It is difficult to establish a numeric threshold. It would simply be unreasonable for a leader to have their family members in more than 50 per cent of photos. Indeed, it is probably unreasonable for them to do so 10 per cent of the time. This constraint creates challenges in coming to broader conclusions about self-presentation style. Finally, is the issue related to the coding of political photography (gendered or otherwise)? While there are certainly issues of subjectivity in the content analysis of text (for example, coding if a tweet is negative or positive), visual photography complicates this. Establishing the main intention or purpose of a photo is difficult, given the amount visual cues that exist. There can be people (numbers/positioning), setting, clothing, facial expression, and so on, all occurring in tandem, and they also could vary to the extent to which they are in the foreground or background. However, the growing importance of visuals on social media means that academic research will need to confront how best to study them. This research note serves an initial volley into this murky area of research within the Canadian context.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the reviewers and especially editor Cameron Anderson for their guidance on this research note. This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).