Although there has been a great deal of work on the politicization of immigration in various countries (van der Brug et al., Reference van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015), comparatively little attention has been given to the question of politicization at the subnational level. In countries with multilevel governance over immigration policies—specifically, federal states such as Canada where jurisdiction over immigration is shared between two levels of government—immigration and integration policies (IIP) are increasingly part of the political agenda at the provincial or regional level but tend to follow very different paths compared to the federal level (Adam, Reference Adam2013; Campomori and Caponio, Reference Campomori and Caponio2013).

Researchers have documented periods of increased political discussion on immigration in Canada (for example, Abu-Laban, Reference Abu-Laban1998, Reference Abu-Laban2004; Paquet and Larios, Reference Paquet and Larios2018); however, open political debate on topics such as immigration and multiculturalism among Canadian policy makers has been relatively limited (Ambrose and Mudde, Reference Ambrose and Mudde2015).Footnote 1 Canada's expansionist immigration policies and accompanying integration policies are generally supported by the public and not often a source of major division among political parties (Trebilcock, Reference Trebilcock2019; Bloemraad, Reference Bloemraad2012). As Canada's IIP sectors have become increasingly decentralized, provincial political actors have become more involved in immigration policy making. As demonstrated by Paquet (Reference Paquet2020), when subnational governments become more active on immigration issues, they bring different concerns, demands and approaches into immigration discussions. For example, Xhardez and Paquet (Reference Xhardez and Paquet2021) note an increasing emphasis and emergence of different stances on immigration in political party platforms in the province of Quebec since 2012. Likewise, in the province of Ontario, media and political pundits speculated that the 2018 provincial electoral campaign would be marked by a mobilization of nativist rhetoric on the right, dovetailing with negative views on immigration. Instead, a more tempered approach emerged, balancing populist concerns regarding an influx of newcomers and the well-established economic benefits of immigration (Budd, Reference Budd2020). These findings reveal how a nuanced account of the politics of immigration at the provincial level is needed in order to fully appreciate how IIP are being taken up in Canadian politics as a whole.

Through a longitudinal analysis, this article examines how IIP are introduced onto the public agenda and framed in electoral debates covered in the media and in party platforms, using the cases of Ontario and Quebec. While these provinces each welcome a high proportion of Canada's immigrants, they provide us with very different subnational contexts. This allows us to observe the distinct forms and degrees of politicization in contexts where immigration is a very present issue but the relationship with diversity and immigration differs. We begin with a discussion of the politicization of immigration-related issues, with a particular focus on the cultural and social contexts in which immigration is framed and comes to be part of the public political agenda. We then provide an overview of Canadian immigration federalism and the unique immigration dynamics of our cases, Ontario and Quebec. Following an explanation of our theoretical framework for identifying the politicization of IIP and of our method, our findings are presented.

While our findings overall point to pro-immigration stances commonly attributed to Canada as a whole, our longitudinal approach allows us to identify when debates happened at the provincial level, the degree of public attention they were given, and whether these instances can point us toward any enduring trends in immigration politicization. It shows that in Ontario, IIP were primarily framed as an economic and social resource. However, following the event of 9/11, new frames began to be introduced, contributing to a heightened salience and polarization. In contrast to Quebec, however, this politicization was not sustained. In Quebec, IIP were only marginally a matter of electoral concern and disagreement until the mid-2000s. This changed following the Hérouxville event, as these topics became salient, and dominant frames of immigration as economic and social resources were challenged by those of immigration as economic and cultural threats.

Toward an Explanation of the Politicization of Immigration

Politicization is the process of political actors bringing issues from private discussions and decision making in closed circles to public debates and scrutiny (Krzyżanowski et al., Reference Krzyżanowski, Triandafyllidou and Wodak2018). In other words, it involves a shift from a “permissive consensus” around a given issue to a “constraining dissensus” (De Wilde, Reference De Wilde2011: 559). This process increases public visibility of issues, intensifies public debates about them and enhances their electoral importance. In doing so, it also opens space for hegemonic narratives, or ways of framing issues, that dominate public discourse to become more visible and potentially disrupted (Krzyżanowski et al., Reference Krzyżanowski, Triandafyllidou and Wodak2018). Instances of politicization on specific issues are significant as they often directly reflect the values, assumptions and priorities of the polity (De Wilde, Reference De Wilde2011: 563). Questions of how certain issues are introduced onto the political agenda, in what form, and to what degree, therefore, are of fundamental importance.

Immigration policies in liberal democracies have traditionally been adopted out of public view. Freeman (Reference Freeman1995) explained this by pointing to a consensus among political parties, one characterized as “almost always expansionary, sometimes status quo” (888). Recent evidence suggests that this pro-immigration consensus has been broken, as immigration and integration are increasingly high on political agendas across Europe and in other liberal democracies (Norris and Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Grande et al., Reference Grande, Schwarzbözl and Fatke2019). Since then, scholars have been particularly interested in understanding under which circumstances immigration and integration have become defined as problems that require action from policy makers.

One important strain of literature highlights the role of far-right parties (Grande et al., Reference Grande, Schwarzbözl and Fatke2019; Mudde, Reference Mudde2007; van Spanje, Reference van Spanje2010; Schain, Reference Schain2006) and centre-right parties (Bale, Reference Bale2008; Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup, Reference Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup2008; Meyer and Rosenberger, Reference Meyer and Rosenberger2015) in bringing immigration onto the political agenda, often capitalizing on a focusing event that draws attention to these issues (Barrero, Reference Barrero2003; Triandafyllidou, Reference Triandafyllidou2018). Far-right and centre-right parties are known to express concerns about immigration, presenting themselves as defenders of the socio-economic and cultural status quo and framing the presence of immigrants as a challenge (Bale, Reference Bale2008). By placing these issues on the political agenda, they often force other parties to pay attention to these issues as well—therefore breaking the pro-immigration consensus by presenting alternative views.

To effectively politicize an issue, political actors have to conceive and present a situation as a problem that needs to be addressed (Baumgartner and Jones, Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993; Rein and Schon, Reference Rein, Schon, Fischer and F1993). They therefore engage in processes of framing by promoting a particular presentation of an issue as a problem in need of a particular solution (Chong and Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007). Broadly defined, framing can be thought of as “selecting and highlighting some facets of events or issues, and making connections among them so as to promote a particular interpretation, evaluation, and/or solution” (Entman, Reference Entman2004: 5). In doing so, political parties draw on existing cultural and social narratives, values and beliefs to produce a given understanding of a problem and the appropriate policy intervention (Rein and Schon, Reference Rein, Schon, Fischer and F1993; Chong and Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007) and place the issue on the policy agenda. For example, Fiřtová (Reference Fiřtová2021) demonstrates how the Conservative party of Canada (2006–2015) engaged in a gradual reframing of immigration in order to reform immigration and refugee policy by raising economic, integration and security concerns that challenged the dominant Canadian frames of incorporation and promotion of immigration (see also Frederking, Reference Frederking2012).

Canadian Immigration Federalism and Immigration in Ontario and Quebec

Although the Canadian Constitution (1867) defines immigration as a shared jurisdiction between the federal government and the provincial governments, the federal government has long retained significant control over the management of this policy area. Yet the 1990s marked a gradual increase in provinces’ power over IIP (Paquet, Reference Paquet2014). While the federal government maintains control over citizenship and is the final authority on immigrant selection, Canada has developed a highly decentralized system of immigration and integration, with provinces increasingly engaged in attracting and selecting immigrants to their region and providing settlement and integration services.

As noted by Paquet (Reference Paquet2014), while all ten provinces have become increasingly active in the management of immigration, they have also converged toward a pro-immigration consensus. The adoption of liberal and inclusive IIP was part of province-building strategies that focus on immigrants as economic and social resources. At the same time, provinces have also adopted very different approaches to engaging with the issues of immigration and integration (Banting, Reference Banting, Joppke and Leslie Seidle2012; see also Leo and August, Reference Leo and August2009; Leo and Enns, Reference Leo and Enns2009; Jeram and Nicolaides, Reference Jeram and Nicolaides2019). To better understand the broader societal narratives and beliefs about immigration that might influence the way political actors frame these topics, we explore Quebec's and Ontario's specific approaches to immigration and integration.

In Quebec, immigration and integration have consistently been approached as part of society-building, regardless of the government in power (Paquet, Reference Paquet2014). The province's significant powers over immigration are the result of successive demands to increase control over the management of this policy area. This level of control has followed claims that since Quebec is a distinct society that needs to protect its culture and language, its provincial authorities need to have an active role in determining who settles there, in order to integrate immigrants in a manner that respects the distinct society of Quebec and facilitate immigrant attachment to Quebec's political community (Barker, Reference Barker2012; Paquet, Reference Paquet2014). To this end, through the Canada-Québec Accord (1991), Quebec acquired powers over the selection, recruitment, reception and settlement of new immigrants, going well beyond that of any other Canadian province. The Canada-Québec Accord authorized Quebec to weigh in on the number of immigrants it admits annually and on the selection of economic-class immigrants who apply to settle in the province. It permits Quebec to undertake its own integration and settlement services guided by the principles of interculturalism. As a model for the integration and administration of ethnocultural diversity, interculturalism aims to ensure the preservation of Quebec's culture (notably by recognizing the status of the majority culture and language) while accounting for diversity and the rights of ethnocultural minorities (Bouchard, Reference Bouchard2011; see Lamy and Mathieu, Reference Lamy and Mathieu2020).Footnote 2 Furthermore, Bill 101 (1977) has paved the way for the francization of the province and, among other things, ensured that immigrants acquire a working knowledge of French upon arrival in Quebec and requires their children to attend French elementary and secondary schools.

Compared to other provinces, Ontario has historically been less active in pursuing control over IIP (Jeram and Nicolaides, Reference Jeram and Nicolaides2019)—for example, the first Canada-Ontario Immigration Agreement (COIA) was not reached until 2005,Footnote 3 and the province only first published a formal immigration strategy in 2012. However, as the most populous province in Canada, the majority of newcomers to Canada settle in Ontario, with the greatest numbers concentrated in the Greater Toronto Area. While Ontario has not had the same concerns about immigration selection and recruitment as Quebec, they sought federal funding comparable to their neighbouring province for settlement services for their growing newcomer population. The province resisted taking on authority for integration before this funding could be secured and during the late 1990s cut provincial funding and downloaded responsibility for settlement services onto municipalities (Paquet, Reference Paquet2014; Jeram and Nicolaides, Reference Jeram and Nicolaides2019). As explained by Paquet (Reference Paquet2014), Ontario's approach to IIP is the result of a response to the needs created by the strong presence of immigrants in the province. It principally involves ensuring social cohesion and maximizing the economic benefits related to the presence of newcomers.

In both provinces, the positions of well-established political parties have generally not been explicitly anti-immigration and exclusionary. As described above, Quebec and Ontario have had divergent pathways to establishing authority over IIP, as well as different motivations (Jeram and Nicolaides, Reference Jeram and Nicolaides2019; Paquet, Reference Paquet2014). Quebec negotiated early for this authority, motivated largely by the desire to protect and maintain its distinct culture as a minority nation and to maintain its demographic weight in Canadian federalism given declining birth rates. Ontario, already a linguistically and ethnically diverse province that faced no trouble attracting newcomers, was less concerned about control over immigrant selection but had concerns about funding settlement services for increasing numbers of newcomers. These different trajectories point to some divergences regarding the dominant immigration frames existing in these provinces. Whereas the economic impact of immigration and immigrants’ social and economic integration are central to Ontario's approach, the impact of immigration on Quebec's cultural and linguistic preservation, together with its economic impact (Paquet and Tomkinson, Reference Paquet, Tomkinson, Pétry and Birch2018), characterizes Quebec's approach. These two provinces, therefore, provide an ideal comparison because of their distinct and divergent relationship with immigration and integration.

Theoretical Framework for Identifying Politicization

Politicization is a process that is frequently defined along two axes: salience and polarization. Salience involves increased political attention devoted to immigration and integration issues, and polarization refers to political actors expressing conflicting positions over an issue and employing contrasting frames (Grande et al., Reference Grande, Schwarzbözl and Fatke2019). Our study mobilizes van der Brug et al.'s (Reference van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015: 7–8) typology of politicization, which outlines four general types, depending on whether the issue is salient and/or polarized. First, a topic can be recognized as a social problem but seen as a settled or private matter that does not require attention from political actors. In this ideal type, the topic is “not even a political issue” (7). Second, a topic can be salient, with political actors agreeing that political action is required to address the issue, while disagreeing about “the ways in which to realise these goals or the priority to give to the issue” (7). The combination of salience and low conflict surrounding an issue is referred to as an “urgent problem.” Third, an issue can be low on the political agenda (not salient), despite political actors having conflictual positions over this issue. In these instances of “latent conflict,” political actors might attempt to decrease the salience of an issue by organizing commissions or consultations. Fourth, an issue is “politicized” when it is both salient and polarized.

In this study, we explore the politicization of immigration and integration issues in Ontario and Quebec because both immigrant selection and funding for settlement services to facilitate integration are covered under federal-provincial immigration agreements. Following Filindra and Goodman (Reference Filindra and Goodman2019), we maintain that immigration and integration policies are fundamentally distinct, while each play a significant role in the lives of immigrants. Immigration policy regulates who is permitted to enter a country and under what conditions, while integration policy refers to how immigrants and their families are treated once they are settled in the country. Moreover, “integration” policies can be exclusionary and marginalizing rather than integrative and are not always directly targeting immigrants (for example, accommodation policies tend to target immigrant, ethnic or national minorities, regardless of status). IIP have become increasingly important, interconnected topics of political discussion and issues of concern for voters in contemporary liberal democracies (Norris and Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019).

Methods

In order to examine how political actors mobilize different frames either to maintain the status quo or to incite politicization of IIP, we focus on political actors’ statements to the media during electoral campaigns, as well as policy statements on IIP contained within electoral platforms from the 1990s to the present for both Ontario and Quebec. Parties’ positions and claims were analyzed in order to highlight patterns of politicization, specifically by determining whether IIP constitutes a non-issue, latent conflict, urgent problem or politicized issue in a given election (van der Brug et al., Reference van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015).

The periods under study correspond to each general provincial election in both provinces from 1987 to 2018, from the moment provinces began to increase their power over IIP (in the 1990s) until the present. We acknowledge that looking only at periods of election campaigns is not a comprehensive look at provincial politics, debates and claims about IIP. However, election campaigns represent moments of increased confrontation between political parties and increased public exposure of these ideas, and they constitute periods during which political parties set their agenda. Moreover, as noted by Pétry and Duval (Reference Pétry and Duval2015), parties generally keep their promises, and thus pledges made on IIP during election campaigns can impact policy.Footnote 4 We maintain that electoral campaigns are thus crucial when analyzing the politicization of an issue.

We examined both electoral platforms and public statements by party representatives in mass media for each provincial election within our period of study. When exploring the politicization of IIP, scholars tend to either explore electoral platforms (Xhardez and Paquet, Reference Xhardez and Paquet2021; Ruedin, Reference Ruedin2019) or political claims in mass media (van der Brug et al., Reference van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015; Carvalho and Duarte, Reference Carvalho and Duarte2020; Urso, Reference Urso2018). We maintain that electoral platforms allow us to accurately evaluate parties’ positions on IIP (see also Ruedin and Morales, Reference Ruedin and Morales2019). However, we argue that by only exploring electoral platforms, we miss a significant part of the story: that is, political debates, discussion, and contestation over issues, as well as the frames that parties employ to promote a particular presentation of these issues to the electorate (see also van der Brug et al., Reference van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015). We argue that exploring both electoral platforms and mass media offers a more detailed portrait of the politicization of IIP.

Using Eureka (a searchable media database), we collected all articles in the Toronto Star (N = 308) and La Presse Footnote 5 (N = 354) featuring the words immigra*, refugee*, asylum, newcomers, international students and family reunification published from the official launch of the election period to the election date, and we selected those that made specific references to the provincial election for analysis.Footnote 6 These two newspapers were selected based on their quality and distribution (being among the most widely circulated newspapers in Ontario and Quebec, respectively). We acknowledge that individual media outlets may have particular political leanings. For this reason, we focused primarily on candidates’ statements (rather than journalistic takes). Party platforms for the Ontario and Quebec elections under study were located and retrieved via POLTEXT,Footnote 7 a database of party platforms in Canadian provincial elections, and statements on IIP were identified.

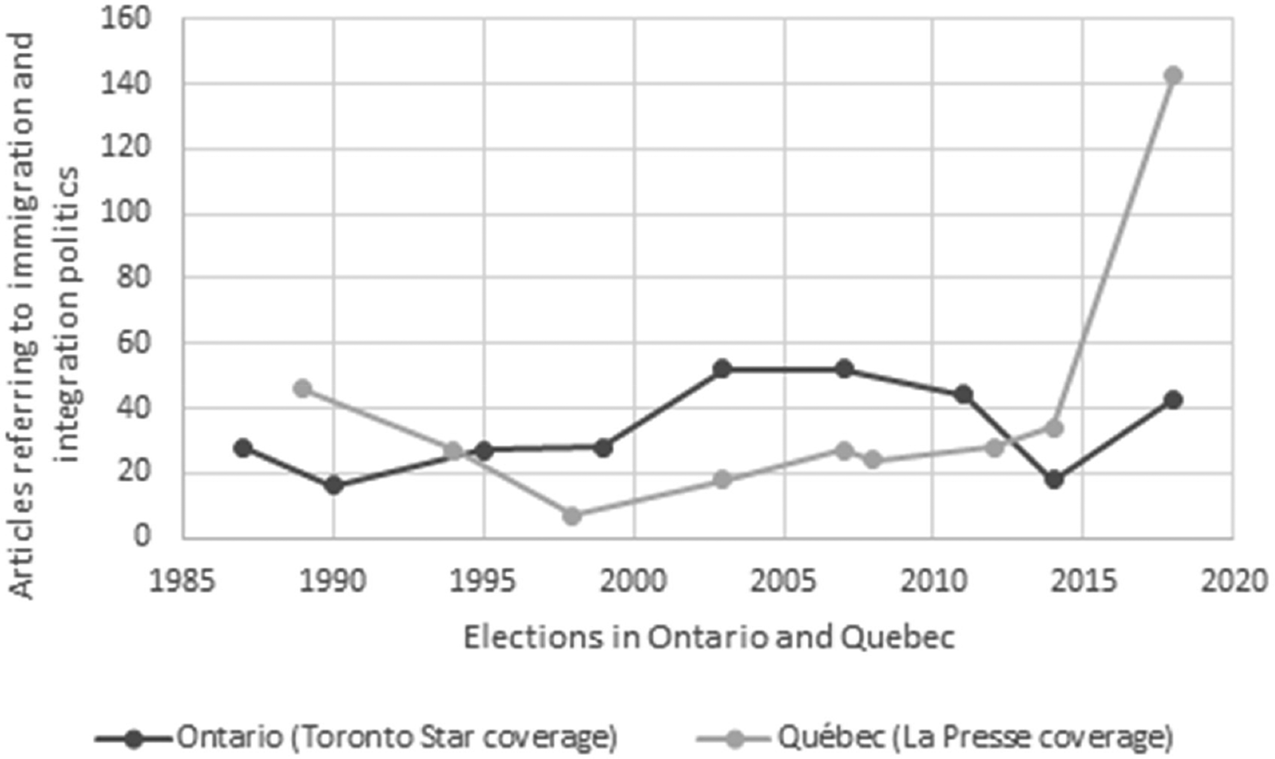

Following van der Brug et al. (Reference van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015), we measured salience by the relative attention to IIP in mass media. Specifically, we looked at the number of articles published that deal primarily with political actors’ claims and stances on immigration-related issues, with a specific focus on variations in the number of articles published during each electoral campaign. As Figure 1 shows, IIP has generally been more salient during electoral campaigns in Ontario than in Quebec. In Ontario, IIP did not become a salient election issue until the early 2000s, but by the mid-2010s was no longer seen as such (perhaps because politicization yielded little electoral rewards). In Quebec, claims about IIP were salient in 1989 and 1994. Following a decrease in 1998, salience gradually increased from 2003 to 2014 and finally peaked in 2018.Footnote 8 This gradual increase can be explained by the growing importance of debates over immigrants’ integration. In 2018, tensions around immigration and integration dominated the political agenda.

Figure 1 Salience of Immigration and Integration as an Electoral Issue in the Media in Ontario and Quebec, 1987–2018

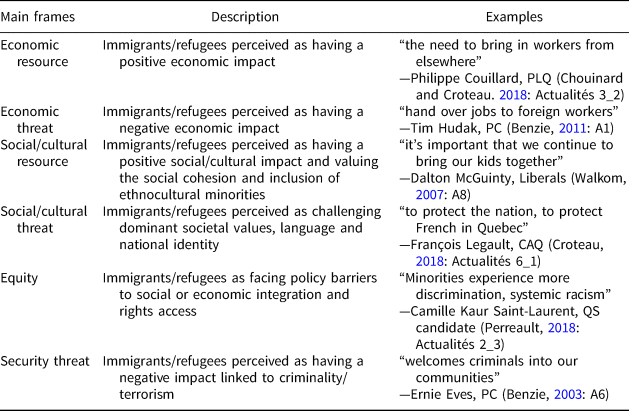

When evaluating polarization, we looked at political parties’ specific positions on immigration and integration and at the way political actors deploy different frames in order to reflect disagreement—for instance, by reframing an issue to oppose another party's positions. We identified inductively an initial set of frames to create a coding scheme, adding new codes throughout the analysis (see Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007). All newspaper articles that quoted public officials discussing IIP and statements referring to IIP provided in party platforms were coded by the authors using NVivo 12 (a qualitative data analysis software). Data was analyzed collaboratively, involving multiple checks to ensure consistent approaches to coding and interpreting data, as well as reviewing and comparing coded work. Table 1 outlines the main frames pertaining to IIP mobilized during Ontario and Quebec elections, along with examples from newspapers illustrating the content of these frames.

Table 1 Description of Immigration and Integration Frames Used in Ontario and Quebec Provincial Election Discourse

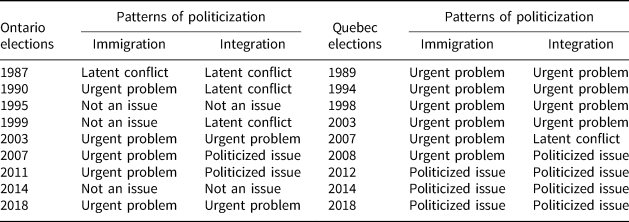

Using these assessments of salience and polarization, we fit IIP issues that emerged in each election into van der Brug et al.'s (Reference van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015) typology to identify instances of politicization (see Table 2). These findings are presented first in an overview of the Ontario case and Quebec case, respectively, followed by a discussion of our conclusions.

Table 2 Patterns of Politicization of Immigration and Integration in Ontario and Quebec Election Campaigns

Ontario: Moments of Politicized Immigration and Integration

This analysis is based on the positions of key parties running in provincial elections in Ontario—namely, the right-leaning Progressive Conservative party of Ontario (PC), the more centrist Ontario Liberal party, and the left-leaning Ontario New Democratic party (NDP). Overall, the most salient topics and frames related to IIP in Ontario, as discussed by electoral candidates in the media and their platforms, included (1) education for ethnic minority and immigrant children and adults as an equity issue but also as an economic resource; (2) recruiting, training and recognizing the credentials of skilled immigrants, as well as addressing employment barriers for them, as an equity issue but also as an economic resource; and (3) provincial control over immigration, primarily framed as an economic resource. The relative salience of these issues varies for each election, as does the degree of polarization. The issue of immigrant representation was also visible in the media; however, it was rarely discussed directly as such by candidates or in platforms. Each main party actively positioned themselves as best representing immigrants and demonstrated some awareness of the importance of the “ethnic vote,” largely by highlighting candidates’ personal or community connections to immigrant experiences rather than by substantive policy proposals.

Ontario election discourse from the late 1980s to the end of the 1990s was largely void of any politicization of IIP, although various IIP related issues did surface as both urgent problems and latent conflicts. For example, the issue of heritage language education for children was an urgent problem that surfaced in the 1987 election, identified in the media as an important issue for ethnic minority and immigrant families. Although not mentioned in any party's platform,Footnote 9 the issue was frequently commented on by candidates in the media, with all three major parties agreeing on the importance of teaching heritage languages (drawing on a social resource framing) but diverging on how best to integrate such a program into the existing education system. Immigrant employment equity, on the other hand, was treated as a latent conflict, with Bob Rae, the NDP candidate, proposing employment equity legislation, and with Larry Grossman, the PC candidate, not seeing this as necessary.

One major event that had on impact on the 1987 election was the negotiation of provincial control over immigration in the Meech Lake Accord. In an attempt to position himself as the candidate allied with Ontario immigrants, Grossman campaigned on the issue, suggesting that allowing Quebec more control over immigration would mean more franco-immigration and less anglo- and allo-immigration for Ontario. However, rather than engaging, David Peterson, the Liberal incumbent, dismissed Grossman's claims as misrepresenting the issue and framed them as an attempt to rally ethnic divisions before an election. The successful Liberal candidate stated prior to the election, “I think provincial news is far more exciting than federal news. . . . I haven't applied my mind to the [immigration] question in great detail. . . . It's not a provincial matter.” (Toronto Star, 1987: A8). In the 1987 election, the issue of Ontario's control over its own immigration is positioned as a latent conflict. Although there may have been disagreement between the two parties on the Meech Lake Accord, the Liberals largely dismissed it as a provincial election issue. This shifts in the 1990 election, where Ontario's control over immigration to its province emerges instead as an urgent problem: an issue of great discussion with parties each expressing a similar goal.

Three elections took place during the 1990s, and despite major ideological swings—for example, from the New Democrats under Bob Rae to Mike Harris’ Progressive Conservatives—IIP were not salient issues in party platforms or the mass media during the election campaigns. Importantly, during the 1990s, federal-level responses to refugees—for example, in response to events such as the arrival of Sikh refugee claimants by boat in 1987 and the intake of refugees due to the war in Kosovo in 1999—were quite prominent in the Ontario media but did not prompt provincial electoral attention. Different parties occasionally commented on the province's increased intake of refugee claimants and subsequent strains on the welfare system; however, the issue did not emerge as salient, and there was no polarization on the intake of refugee claimants at this time (not an issue). This is the case despite the increased popularity of framing refugee claimants through discourses of criminalization that emerged in the 1990s in Ontario and the overall anti-immigrant sentiment in Harris’ policy record and earlier public statements (Pratt and Valverde, Reference Pratt and Valverde2002). Equity issues for immigrants and ethnic minorities (specifically, employment discrimination and disproportionate negative impact of welfare reform) are discussed in each election as latent conflicts—for example, in 1999, as a Liberal and NDP critique of the record of cuts to welfare and education funding and the dismantling of employment equity legislation by the PC incumbent (Mike Harris). Implicit in much of the immigrant employment equity discussion is also the economic resource frame: that it is beneficial not only for immigrants themselves but for Ontario as a whole.

The following three elections (2003, 2007, 2011) were dominated by the Liberal party under the leadership of Dalton McGuinty. The 2003 election took place at a time when Ontario was in the process of negotiating with the federal government for more provincial control over immigration (and the immigration of skilled workers, in particular). Broadly speaking, this particular point was not an issue of contention among parties (urgent problem). During this period, however, we begin to see increased salience (see Figure 1) and polarization. In particular, we see the PCs introducing new frames, such as security threat and economic threat, into the election discourse.

The heightened securitization discourse following the terrorist attacks in New York on September 11, 2001, prompted the introduction of a new frame into the 2003 provincial electoral discourse: immigrants as a security threat (see also Frederking, Reference Frederking2012). This new framing and the attention and debate it garnered represent the first instance of politicization of IIP during our study period. Within their party platform, the PCs under Ernie Eves laid out an extensive “Passport to Ontario” immigration plan, which, in addition to “bringing good people into Ontario” (for example, skilled workers) (PC Platform, 2003: 1), emphasizes “keeping bad people out of Ontario” (3) and “stopping people from taking advantage of Ontario” (5), while explicitly linking current immigration selection procedures to crime and terrorism. This frame is integrated into multiple policy papers that make up the platform and includes issues such as immigration fraud (also linked to welfare and healthcare fraud), border security and terrorism, as well as a proposal for a provincial-level deportation enforcement program (referred to as a “Fugitive squad”). Eves, stated, for example:

War criminals, would-be terrorists and other bad people get into Canada because the federal Liberals have created a system that seems to work for no one. . . . The same people who have saddled Ontario with a broken immigration system that shuts the doors on literally tens of thousands of skilled workers yet seemingly welcomes criminals into our communities (Benzie, Reference Benzie2003: A6).

The provincial Liberals and New Democrats discuss immigration more sparingly in their platforms using economic benefit and equity frames but were critical of these statements in the media—for example, as stated by McGuinty, “[The PCs] luxuriate in divisiveness, in pitting one group against the other. What they fail to do is understand that leadership is about ensuring that you bring people down the high road” (Brennan, Reference Brennan2003: A6).

The security threat frame was not present in the following elections. However, alongside the economic resource frame present in most platforms, we see new frames, such as economic threat and equity, being used more actively in relation to education and employment sectors, leading to increased salience and polarization. For example, just prior to the 2007 election, the issue of public funding for private faith-based schools was politicized. The Conservatives put forward a policy that extended funding for Muslim and Jewish schools (in addition to already funded Catholic schools) as a measure of “fairness” and religious accommodation (equity frame) (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2020: A1). The Liberals, opposing this proposal, drew on the social resource frame to argue that this policy invites “children of other faiths to leave the publicly funded system and become sequestered and segregated. . . . It is important that we continue to bring our kids together, so that they can grow together and learn from one another” (Walkom, Reference Walkom2007: A8). In another example of politicization, this time during the 2011 election, the Liberal party proposed a tax incentive for employers who hired immigrant workers in order to facilitate economic integration, which the PC candidate, Tim Hudak, referred to as “an affirmative action program for foreigners” (Toronto Star, 2011: A22). Mobilizing the frame of immigrants as an economic threat, Hudak continued to argue against the proposition to “hand over jobs to foreign workers when [there are] so many unemployed in Ontario” (Benzie, Reference Benzie2011: A1). There was a backlash against Hudak's characterization of immigrant Ontarian workers as “foreign workers,” which McGuinty responded to using the social resource frame to promote unity and social cohesion—for example, “In my Ontario, there's no us and them, there's just us” (Benzie, Reference Benzie2011: A1).

The politics of division that emerged in the previous elections (immigrants framed as security and economic threats) was much less salient in the 2014 election, which saw Kathleen Wynne of the Liberal party voted in as premier. Aside from a brief mention of immigrants as an economic resource in the PC platform, there were very few direct mentions of IIP in the party platforms or media. Wynne expressly rejected the “hateful politics of division in Ontario” (Toronto Star, 2014: A6), and policy analysts expressed surprise that no party actively engaged in identity-based politics (Vincent, Reference Vincent2014: A8). IIP was not an issue in this election. Importantly, this was at a time when the federal government had cut health benefits for refugee claimants and the Ontario government was covering the costs, yet these costs were not politicized as election issues.

We can contrast this with the 2018 election, where every major party mentions immigration in their platform—mostly mobilizing economic resource and equity frames. The PC and Liberal platforms focus on issues such as credential recognition and the need for employment and language training for new immigrants, with the Liberal platform also touching on equity issues such as anti-Black racism and support for multicultural communities as a social/cultural resource. The equity frame was most visible in the NDP platform, with Andrea Howarth proposing “Access Without Fear policies for police, health, and social services” (NDP Platform, 2018: 68), even suggesting Ontario could be a “sanctuary province” (68). This is notable as the first explicit mention by a major political party of equity for precarious status residents of Ontario as an election issue.Footnote 10 Despite the wide range of issues present in the platforms, only immigrant employment was salient in the media as an urgent issue. Although the issue briefly appeared to be veering in the direction of politicization when PC candidate Doug Ford, while discussing a federal program aimed at bringing newcomers to northern Ontario, framed immigration as an economic threat, stating, “I'm taking care of our own first” (Rushowy and Benzie, Reference Rushowy and Benzie2018: A12). Both Liberal and NDP leaders spoke out against this rhetoric. However, rather than insisting on the economic threat frame (as Hudak did in 2011), Ford backtracked his comments and refrained from politicizing immigration in the press during his campaign, instead speaking often of the broad support he had from diverse communities. At the same time, Ford, who would ultimately win the election, continued to express support for candidates running as PCs who engaged in more active politicization of immigration, specifically anti-immigrant discourse (Paradkar, Reference Paradkar2018: A1). As Budd (Reference Budd2020) argues, Ford's brand of populism reveals a “subtle and often covert neoliberal racial politics” whereby inclusive rhetoric masks the ways in which policy proposals nonetheless “reinforce social racial hierarchies” (179).

Quebec: An Incremental Politicization of Immigration and Integration

For the Quebec case, the analysis is based on the positions of the key parties running in provincial elections during the period under study: the right-leaning Action démocratique du Québec (ADQ), which dissolved and merged with the also right-leaning Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) in 2012 (Boily, Reference Boily2018); the more centrist Parti libéral du Québec (PLQ); the centre-left leaning Parti québécois (PQ); and the left-leaning Québec solidaire (QS) (Collette and Pétry, Reference Collette, Pétry and Pelletier2012). Up until 2007, four main topics related to IIP have dominated electoral agendas: (1) selection of francophone immigrants and immigrants’ knowledge of the French language, (2) regionalization, (3) representation and discrimination of cultural minorities and (4) integration and the promotion of intercultural understanding. These pledges and claims framed immigration as an economic and social resource for Quebec, highlighting the positive value of immigration for the province's (national) development. The analysis notes a shift starting in 2007, during which issues of representation, discrimination and intercultural understanding became less apparent in both the media and electoral platforms. Instead, new pledges were discussed, including (1) a Quebec constitution and citizenship, (2) Quebec's powers over immigration,Footnote 11 (3) secular values and (4) reducing the number of immigrants admitted annually. These pledges were accompanied by frames of immigration as a cultural and economic threat and resulted in conflicts between political parties.

The analysis demonstrates that from the 1989 to the 2003 elections, topics related to immigration and integration were not politicized in Quebec elections and were instead positioned as urgent problems. This is in line with Xhardez and Paquet's (Reference Xhardez and Paquet2021) analysis, which shows that the question of whether Quebec should remain within the Canadian federation or not has long dominated Quebec politics, thus setting aside traditional left-right cleavages that tend to characterize IIP. Immigration was presented by different parties as means to different ends, with the parties maintaining the frame of immigration as an economic and social resource for Quebec in both their platforms and in the newspapers. An example of this is the 2003 election, where the ADQ suggested using immigration as a way to offset labour shortages, while the PLQ recommended ways to favour the retention of immigrants to maintain Quebec demographic weight in Canadian federalism given declining birth rates and population aging.Footnote 12 Integration, for its part, was brought into public focus during election campaigns, yet there was no disagreement among political parties regarding the goals that had to be realized. For instance, primarily framing immigrants as a social resource, parties agreed that political action was required to achieve greater francization, to increase political representation, to encourage immigrants to live in rural areas of the province and to promote integration. These topics were not depicted as being central electoral issues, and immigration was described by journalists as “too complicated and delicate” to be an electoral concern (Leblanc, Reference Leblanc1989: A5).Footnote 13 This was even more apparent in the 1998 electoral campaign, where these topics were addressed in party platforms but ignored in the newspapers.

Changes in electoral dynamics regarding IIP started to become evident during the 2007 electoral campaign, launched shortly after the Hérouxville municipal council adopted a code of conduct for immigrants. The story of the Hérouxville code of conduct generated public debate in the province, as it was criticized for offering a harmful caricature of Muslim immigrants (Pottie-Sherman and Wilkes, Reference Pottie-Sherman and Wilkes2014) but also caused many Quebecers to question whether the province had gone too far in accommodating religious and ethnocultural minorities. In this context, a few days before calling the Quebec election, the Liberal government led by Jean Charest launched a public hearing in an attempt to calm the debate about accommodation, arguing that ongoing debate “serves more division than comprehension” (Charest, Reference Charest2007: A16) and pledging to follow the recommendations of the commission.Footnote 14 Mario Dumont, leader of the ADQ, however, opposed Charest's decision to put in place an inquiry and forgo debate of reasonable accommodations (Chouinard, Reference Chouinard2007b: A2). The ADQ suggested that reasonable accommodations threaten “the true nature of Quebec identity” (Ouimet, 2007: A7) and argued for a constitution setting out Quebec's “identity and values” (ADQ Platform, 2007: 5) in order “to formalize who we are and to favour better integration for newcomers” (Perreault, Reference Perreault2007: PLUS3). The party was the only one to present immigrants’ integration as a political issue at this time by raising the question of Quebec values and framing immigration as a social and cultural threat. Drawing on the equity frame, André Boisclair, leader of the PQ, argued instead that intolerance and exclusion of minorities in Quebec should be the main topics of concern, not reasonable accommodations—which, he argued, could be accorded to individuals without depriving others of their rights (Chouinard, Reference Chouinard2007a: A8). The 2007 campaign marked an increase in the salience of debates over integration and the introduction of new frames to discuss IIP (that is, the beginning of the politicization of integration). Yet despite integration being an issue of great discussion in the media and central in the ADQ's platform, it was not a major component of the platforms of other parties, overall—with the PLQ attempting to transform the issue into a latent conflict and the PQ not engaging with ethnocultural and religious accommodation in its platform.

The 2008 electoral campaign continues this trajectory of increased politicization of integration, framed again as a potential social/cultural threat to Quebec values and French language. During the campaign, while the PLQ maintained that the commission on reasonable accommodations “allowed us to lay the foundations of a consensus” about integration (Beauchemin, Reference Beauchemin2008: A14), the ADQ rejected this positioning of integration as a latent conflict and reasserted the necessity of dealing with this issue. The PQ, for its part, proposed the creation of a Quebec citizenship with knowledge of the French language as one of the eligibility criteria for newcomers. The PQ argued for expanding Quebec's language laws, restricting the language of communication for government officials, and increasing Quebec's powers over immigration to “preserve [Quebec] identity” (PQ Platform, 2008: 26). During this campaign, all political parties argued for increasing immigration to deal with labour shortages, drawing on the frame of immigration as an economic resource. Interestingly, however, the ADQ expressed in the media that the increase in immigration intake should be “proportional to Quebec's capacity to integrate [immigrants] into the labour market”—adding that, at the moment, the “unemployment rate is twice as high among immigrants in Quebec” and stressing “problems related to francization” (Gilles Taillon, quoted in La Presse, Reference Beauchemin2008). While not reflected in the official party platform, this comment highlights a shift from previous ways of framing immigration as a potential economic threat.

The 2012 and 2014 electoral campaigns contributed to the incremental increase in the politicization of integration, with political parties expressing conflicting goals, and saw the beginning of the politicization of immigration in particular. Mobilizing the social/cultural frame of immigration as a threat to French language and Quebec values (including secularism), the PQ, led by Pauline Marois, reintroduced the question of accommodations for religious and ethnocultural minorities. This move can be seen as an attempt to recapture nationalist votes that were shifting to the ADQ/CAQ, who were mobilizing a new nationalist discourse based on language and culture (see Noël, Reference Noël2014). Specifically, the PQ announced in the media that it would ban the wearing of religious symbols for all public employees—a proposition later called the Quebec Charter of Values that became central in the PQ's election platform in 2014. It also pledged to expand Bill 101 and to extend their Quebec citizenship proposal by adding French-language criteria for elected officials.

Although other parties were less vocal about these pledges during the 2012 campaign, in 2014, both QS and the PLQ asserted their opposition to the proposed restrictions on the display of religious symbols in defence of minority rights (Pratte, Reference Pratte2014: Débats écran 2). The CAQ, for its part, supported “the adoption of a Charter of Secularism that affirms the religious neutrality of the Quebec State” (CAQ Platform, 2014: 23). It also proposed that immigrants must learn the French language before being granted permanent residency, that Quebec's selection powers over immigration should be increased and that the number of immigrants admitted annually into Quebec should be decreased. According to one CAQ candidate, this was necessary to “better select them” and stop “importing unemployment” (Le Bouyonnec, quoted in Bisson, Reference Bisson2012: A16). These proposals were all presented as ways of ensuring immigrants’ linguistic and economic integration, mobilizing frames of immigrants as cultural and economic threats. The argument in favour of limiting immigration levels represented a shift from previous consensus across political parties regarding the frame of immigration as an economic resource for Quebec. It was strongly opposed by the PLQ, who argued that Quebec needed immigrants to address labour shortages.

Following the gradual increase in debate surrounding immigration and integration in both the 2012 and 2014 electoral campaigns, the 2018 electoral campaign culminated in a significant intensification in salience (see Figure 1) and polarization as IIP became a key issue—perhaps even, for some, the election's “ballot-box issue” (Lessard, Reference Lessard2018b: Actualités 10). Building on the social/cultural frame of immigration as a threat to Quebec values and French language, the CAQ played a central role in launching the debate by suggesting an increase in Quebec's selection power over immigration and a decrease in the number of immigrants admitted annually, as well as the implementation of French-language and values tests for newcomers and a ban on wearing religious symbols for public servants. These proposals—justified by the CAQ, in part, by the fear that “our grand-children will no longer speak French” (Legault, quoted in Lessard, Reference Lessard2018a: Actualités 4)—generated intense debates, as other political parties expressed their disapproval and suggested alternatives or opposing pledges. For instance, Philippe Couillard, leader of the PLQ, rejected the CAQ's alarmist framing of the disappearance of the French language and accused Legault of “raising fear” with his proposition to revoke the selection certificates of immigrants failing the French-language or values test, while Jean-François Lisée, leader of the PQ, maintained that this would create “undocumented immigrants on Quebec territory” and argued instead to make knowledge of French language a condition for immigration (Chouinard et al., Reference Chouinard, Croteau and Pilon-Larose2018: Actualités 2). Ruba Ghazal, a QS candidate, was critical of the economic burden that imposing a French test would have on immigrants (Lévesque, Reference Lévesque2018: Actualités 9_4). In an attempt to depoliticize the question of immigration levels, the PQ pledged to make this decision a responsibility of the auditor general of Quebec, while positioning itself in favour of decreasing levels of immigration in the media. The PLQ argued for keeping the same threshold levels (maintaining the frame of immigrants as an economic resource), and QS maintained a stance of “not wanting to contribute to a debate about immigration” (Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, quoted in Béland, Reference Béland2018: Dossier special 5). The period just prior to the 2018 electoral campaign was characterized by salient debates regarding an influx of irregular border crossings in Quebec, an issue that was politicized by political parties in the media at the time; however, it garnered little attention during the election itself. Prior to the election, drawing on an economic threat framing, the CAQ maintained that this issue needed to be managed by the federal government, while QS, drawing on an equity framing, argued for suspending the Canada-U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement; the PQ also supported this position in the media, while stipulating in its platform that only a sovereign Quebec could manage its borders (PQ Platform, 2018: 18). During that electoral campaign, both immigration (the number of immigrants admitted annually, Quebec powers over immigration, and irregular border crossings) and integration (including topics related to accommodation of religious and ethnocultural minorities) were presented as political issues that needed to be managed.

Conclusion

Although questions related to immigration and integration are contested issues in many liberal democracies, few studies focus on the politicization of immigration in the Canadian context—and even less so at the subnational level. Because the politicization of issues can be very space- and time-specific (De Wilde, Reference De Wilde2011: 563), we consider this a significant knowledge gap in our understanding of IIP and their politicization. Our comparison of two subnational case studies, Ontario and Quebec, highlights that politicization involves different degrees and dimensions (that is, an issue can be more or less salient and/or polarized) and that it can be framed in different ways by political actors—thus producing particular dynamics in each subnational context. To effectively politicize IIP, political actors have to compete in convincingly framing these issues, with their success notably depending on existing narratives and beliefs on the impact of immigration to a given society (see also Fiřtová, Reference Fiřtová2021).

In Quebec, following the Hérouxville event, candidates were able to tap into the province's insecurity about the preservation of its language and culture. Quebec's subsequent overall more restrictive stance on IIP can be seen as the result of electoral competition and a mobilization of the existing frame of immigration posing a threat to the minority nation, as we saw when the ADQ and the CAQ brought IIP into electoral campaigns, thus forcing other parties to take a stance on these issues. Dominant frames of immigration as economic and social resources were challenged by those of immigration as economic and cultural threats.

The political context in Ontario, including the province's relationship to immigration and integration, is quite different from Quebec's. Ontario has consistently received the majority of new immigrants to Canada, the majority of whom settle in the Greater Toronto Area, Canada's epicentre of multiculturalism. While the province experiences challenges related to integration and has lobbied for more control over immigration, the presence of newcomers is not framed as a threat to cultural identity but rather as a part of it. That said, concerns still exist over the impact of immigration within the province, and politicians have, at times, tried to leverage that. The analysis of the Ontario case highlights instances where IIP are politicized, introducing new frames in opposition to well-established economic and social benefit discourse—in this case, economic and security impacts, in contrast to cultural impact. There is also strong resistance to this framing—for example, the Liberal party consistently responds in a way that discredits this framing as a politics of division.

In line with other studies, the analysis also shows that the politicization of immigration can happen even in the absence of far-right parties, the usual suspects for breaking pro-immigration consensus (Bale, Reference Bale2008; Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup, Reference Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup2008; Xhardez and Paquet Reference Xhardez and Paquet2021). Right-leaning parties, namely the ADQ/CAQ in Quebec and the Progressive Conservative party of Ontario (PC), played a key role in politicizing IIP (or attempting to), often capitalizing on a focusing event. In Ontario, the PC party took the lead in attempting to politicize IIP. It is notable, however, that not every PC leader engaged in this kind of politicization, and when those politics were more present in election discourse, it did not pay off (even in the wake of 9/11). The degree of polarization over IIP, therefore, varies for each election, as does its relative salience. In Quebec, integration was long positioned as an urgent problem—up until the Hérouxville event, which enabled right-leaning parties to gradually give salience to and enhance the polarization surrounding IIP. The ADQ and, later, the CAQ brought forward qualitatively new frames for understanding immigration and belonging in Quebec, which appealed to the francophone electorate at a time when the political party dynamics in Quebec were shifting away from the federalism/sovereignty divide (see Montigny, Reference Montigny2016; Noël, Reference Noël2014).

Lastly, this research demonstrates that when political actors take stances on IIP in mass media, it is not always reflected in party platforms, and vice versa. This suggests that only looking at electoral platforms or mass media misses a significant part of the story. While electoral platforms provide parties’ official positions on IIP, mass media speaks to the salience of these issues among political parties, while also revealing political debates and contestation over issues (including how parties react to and criticize other parties’ claims and pledges). This is especially relevant as the process of politicization involves increased public involvement with political parties and, consequently, a higher degree of resonance among the wider society (see also Krzyżanowski, Reference Krzyżanowski2018).

This article offers a nuanced account of politicization of immigration and integration at the subnational level in Canada and speaks to the unique ways in which IIP emerge as political issues (or not) in the context of electoral campaigns. To this end, this work lays the groundwork for future studies on the politicization of immigration at the subnational level. In particular, comparing the politicization of IIP to other policy issues or examining how IIP are politicized beyond the electoral campaign period would be key to further developing our understanding of politicization.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank members of the Centre for the Study of Politics and Immigration, specifically Antoine Bilodeau, Mireille Paquet and Catherine Xhardez, as well as the two anonymous reviewers, for insightful comments on earlier drafts of this article.