Introduction

The involvement of municipal governments and civil society actors in policy-making processes traditionally associated with senior levels of government is now well acknowledged (Guiraudon and Lahav, Reference Guiraudon and Lahav2000). It corresponds to the growing awareness that despite remaining disconnected from the major sites of political decision making, local and societal actors matter when it comes to tackling complex issues such as climate change, homelessness, economic development, employability, health or immigration. In immigration, the inclusion of such actors is often presented in the literature as the “local turn” (Caponio and Borkert, Reference Caponio and Borkert2010).

This article focusses on two Canadian political entities participating in this “local turn” and illustrates a dual shift in the policy process downward to municipalities and outward to organized civil society, such as actors from francophone minority communities (FMCs). FMCs refer to the one million francophones who live in minority communities in provinces and territories outside Quebec. These minority communities are served by myriad institutions and community-based organizations that defend and promote language rights, lobby governments, offer sociocultural programming and deliver services in French. In each province and territory, a representative organization draws together this constellation of community-based organizations.Footnote 1 At the national and international levels, the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne du Canada (FCFA) serves as FMCs’ main voice and advocate.Footnote 2

If the roles of municipalities and FMCs in immigration have been examined separately, researchers have, with few exceptions (notably Andrew, Reference Andrew, Tolley and Young2011), overlooked the comparison. At first glance, municipalities and FMCs have little in common. Yet one similarity is that despite having no specific jurisdictional responsibilities in immigration and occupying a nondominant position in the policy-making process, both municipalities and FMCs play a vital role in mediating interventions to meet local needs, deal with governance challenges and seize opportunities related to immigration, notably through their inclusion in federally funded collaborative networks, such as the Local Immigration Partnerships (LIPs) and the Réseaux en immigration francophones (RIFs). In this context, this article asks: Why is their involvement possible? Which forms does it take? What does it tell us about policy making and, more generally, about collaborative and multilevel governance arrangements?

To answer these questions, I use a “most different cases” comparative design to study three cities (Moncton, Winnipeg and Vancouver) and three FMCs in their respective provinces (New Brunswick, Manitoba and British Columbia). The interest of this comparative design relies upon identifying possible forms of convergence, particularly in terms of governance, despite the presence of key institutional differences. This type of comparison is in line with the resurgence of territory and locality in comparative politics (Broschek et al., Reference Broschek, Petersohn and Toubeau2017), as well as with the move beyond “methodological nationalism” in migration studies (Glick Schiller and Caglar, Reference Glick Schiller, Caglar, Schiller and Caglar2011).

This research highlights the roles of ambiguities regarding governance processes and offers new insights into the significant characteristics of the “local turn.” In the Canadian case particularly, Tuohy (Reference Tuohy1992) recognizes that ambiguity can lead to policy innovation and diffusion but underlines that this might be accomplished at the expense of the broader public. Her main contribution is to show how ambiguities are “quintessential” to the country's politics and policies. The specificity of ambiguity in Canada is its institutionalization—namely, its embeddedness within the structures of the provincial and federal governments. But what we are lacking now is an understanding of how these ambiguities play out in the context of greater collaboration beyond traditional elites.

This article aims to fill this void by drawing attention to the fact that engagement in collaborative governance does not mean that the actors engaged in these forms of collaboration inevitably share the same vision about public action. On the contrary, conflicts and competition are at the heart of governance mechanisms, and they steer social and political processes (Le Galès, Reference Le Galès2011). Individuals and groups have different interests, goals and priorities. However, agency is not a simple matter of adding together actors’ strategies: their expectations and interests are structured by institutions and by the meanings they give to institutions. This is why ambiguities are key to public policy making: they “provide critical openings for creativity and agency; individuals exploit their inherent openness to establish new precedents for action that can ‘transform the way institutions allocate power and authority’ within institutions and among them” (Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney and Thelen2009: 12).

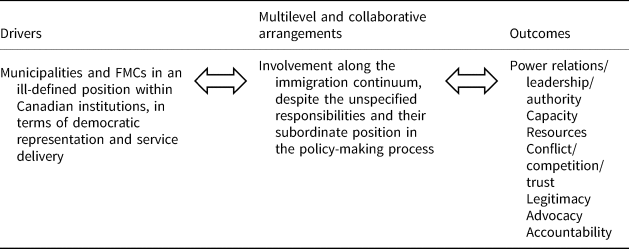

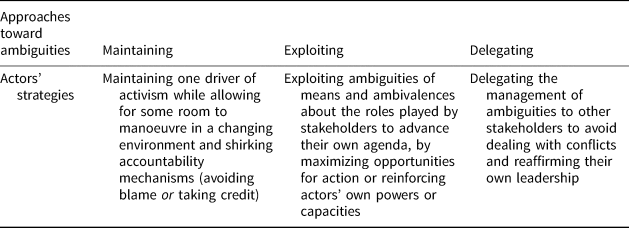

Therefore, this article shows that ambiguities are both (1) a condition for increased participation on the part of municipal governments and civil society actors along the continuum of immigration, and (2) an outcome of such participation, notably in the LIP and RIF networks. The article then presents three approaches that actors adopt as they navigate within a collaborative and multilevel governance framework, namely “maintaining,” “exploiting,” or “delegating” the management of ambiguities.

Canadian Ambiguities in Collaborative and Multilevel Governance Arrangements

Municipalities and FMCs share a subordinate position within Canadian institutions. In the early 1980s and the subsequent constitutional debates, both municipalities and FMC organizations campaigned for stronger constitutional status. Municipalities sought to gain a formal recognition that could protect them from the discretionary power of the provinces. FMC representative organizations asked for a formal recognition of a special status within the Constitution and for a constitutional consecration of their collective rights (Léger, Reference Léger, Cardinal and Forgues2015). The failure to gain more autonomy and authority through federal constitutional amendment has led municipalities and FMC organizations to develop different strategies conducive to more incremental changes in their roles and responsibilities.Footnote 3 In Canada, such implication has been studied through concepts such as “deep federalism” (Leo, Reference Leo2006) or “urban governance” (Andrew et al., Reference Andrew, Graham and Phillips2002) as a way to better account for the involvement of these actors in the federal regime. Moving away from the traditional institutional focus on “strong” or “weak” jurisdictional powers, this body of literature studies the agency and discretionary powers of local governments (Smith and Stewart, Reference Smith, Stewart, Young and Leuprecht2006). Similarly, a notion such as “shared governance” (Forgues, Reference Forgues2012) highlights the inclusion of FMC representative organizations in policy making as well as their need to innovate in order to respond to the challenge of rethinking the nature of their own place within Canadian federalism (Cardinal and Forgues, Reference Cardinal and Forgues2015).

These frameworks share a common attempt to account for the dynamics between stakeholders and render the resulting policy-making process more intelligible in a context where traditional actors, such as the federal and provincial governments and their bureaucracies, are no longer the only legitimate players. The importance of building relationships among actors—whether from the government, private or civil society sectors—has been referred to as the “collaboration imperative” (Kettl, Reference Kettl2006). Besides the complex and interrelated nature of political problems themselves, reasons for collaboration include the challenge of providing, without duplicating, quality services; the desire to achieve greater coordination within different departments and divisions; the need to find innovative solutions that reach beyond administrative silos; the sharing of and sharing in both expertise and resources; and the decentralization and deconcentration of powers that make the challenge of coordinating all that much more difficult (Williams, Reference Williams2012). All of this constitutes—when it is at its best—what this literature calls “the collaborative advantage” (Huxham, Reference Huxham1993; Doberstein, Reference Doberstein2016).

Today, few would question the fact that collaboration has become central to policy making. Nevertheless, collaboration cannot, in itself, be thought an advantage. How do we create a “common good” when different interests, various cultures and multiple forms of management and responsibility coexist? The conditions of effective collaboration, therefore, are key to collaborative governance arrangements (Ansell and Gash, Reference Ansell and Gash2008). Likewise, the reasons why governance can become dysfunctional—including the frustration caused by low levels of participation in the network, bad relations or a lack of trust among actors—are also explored (Rigg and O'Mahony, Reference Rigg and O'Mahony2013). One source of such problems is the ambiguity surrounding the missions, resources, capacities, responsibilities and accountabilities of different organizations (Kettl, Reference Kettl2006). As a result, it is generally recommended that ambiguities be clarified so as to ensure a successful collaboration (Paquet and Andrew, Reference Paquet, Andrew, Cardinal and Forgues2015). And yet, it is often the ambiguity surrounding these issues that serves to justify the importance of collaboration. Therefore, ambiguities are hard to preclude. To cope with ambiguity, actors try to attach meanings to it (Zahariadis, Reference Zahariadis2003).

As defined by Matland (Reference Matland1995), ambiguity can refer to an “ambiguity of goals” or an “ambiguity of means.” The ambiguity of goals refers to actors’ differing interpretations of policy goals or institution mandates. Their framing depends on the multiple social and governmental “sense-makers” who have diverging interests and expectations (Dewulf and Biesbroek, Reference Dewulf and Biesbroek2018). In this view, ambiguity is not considered something to suppress; rather, it is a necessary condition to aggregate competing interests and values, in particular to avoid antagonizing actors and to favour incremental changes through flexibility in implementation (Matland, Reference Matland1995). “Ambiguity of means,” on the other hand, implies ambiguities about the roles played by various stakeholders and refers to a complex policy-making environment. This is notably the case for partnerships involving actors playing multiple roles, such as “government agencies as both funders and partners; local government as both government and community representatives, and community organizations as both service providers and community representatives” (Larner and Butler, Reference Larner and Butler2005: 93). The work of steering partnerships or networks is often under the purview of the main funding body and can lead to co-optation, or “institutionalized subornment,” of other stakeholders (Doberstein, Reference Doberstein2013). As shown by Kassim and Le Galès (Reference Kassim and Le Galès2010), this ambiguity of means may be used as a smokescreen to hide debates about the policy content as well as to depoliticize issues. Likewise, when civil society actors play an active role in policy making, they might seek to promote their interests before public benefits and outcomes. This creates potential accountability concerns: the inclusion of private and nonprofit actors does not negate institutional constraints and constitutional responsibilities. Therefore, elected governments are still held accountable and might be tempted to hold the other stakeholders under “varying degrees of control or supervision” (Doberstein, Reference Doberstein2013: 589).

A “Most Different Cases” Comparative Design

The governance of immigration seems a particularly fruitful point of focus, given the increasing implication of municipal and civil society actors in this area. Reasons for this implication include improving their economies, modulating the social fabric of their communities, being more responsive to specific immigrants’ needs, filling policy gaps, developing their capacities or counterbalancing more restrictive approaches to citizenship. Case selection is based on the “most different systems” design: besides providing a stronger basis for coherent explanations in small-N studies, this methodological strategy features forms of convergence in unexpected contexts (Anckar, Reference Anckar2008). While acknowledging the institutional differences between (and within) municipalities and FMC organizations, the selection is, in fact, based on diversity in terms of the relative size of total population, percentage of immigrants and francophones (as well as the percentage of immigrants within the francophone population) within each metropolitan area. As a result, I carried a case-oriented approach to cross-case analysis (Khan and VanWynsberghe, Reference Khan and VanWynsberghe2008) in the greater Moncton, Winnipeg and Vancouver areas. The variety of these configurations is illustrated in Table 1. Details at the provincial, metropolitan and municipal levels are included in the Appendix.

Table 1 Comparison of Metropolitan Populations (2016 Census): Relative Size of Total Population, Immigration Status and Official Minority Language*

* In comparison with the other metropolitan cases in Canada, except those of Quebec.

To support this comparison, I have combined a document analysis (of policies, action plans and programs) with semi-structured interviews conducted with 17 key actors at the community, municipal and federal levels in 2017–2018. I used the NVivo program for coding documents and interviews. Quotations originally in French have been translated.

Ambiguities as Drivers of a “Local Turn” in Immigration

Municipalities and FMC organizations are in an ill-defined position within Canadian institutions. Two main ambiguities characterize them: one involving mandates and the other involving status. The ambivalence about mandates can be understood as an ambiguity about goals, whereas the ambivalences about status mostly speaks to an ambiguity of means and about the legitimacy of these entities as political actors.

An ill-defined position within Canadian institutions

First, tensions between political representation and services delivery characterize both municipalities and FMC organizations. Municipal governments share fundamental characteristics with their provincial and federal counterparts, including an elected representative assembly and the power to both levy taxes and use force. Municipalities also enjoy strong electoral legitimacy since mayors are directly elected by the population. Nevertheless, it is often assumed that they are apolitical institutions mostly dedicated to service delivery, similar to hospitals or schools. Unlike municipalities, FMC organizations do not have legislative or taxation powers; they operate as a constellation of civil society actors dedicated to lobbying governments and service delivery, rather than as political communities (Traisnel, Reference Traisnel2012). Yet each provincial or territorial FMC representative organization holds a general assembly where members-only elections are held.Footnote 4 Since they claim to speak for francophones in their province or territory as a whole—regardless of the actual number of members they represent formally—a mechanism of democratic representation similar to that of governments is therefore at stake (Gallant, Reference Gallant2010).

Second, ambiguities also frame the roles played by municipalities and FMCs. In spite of a general shift toward more autonomous municipal governments, the 2018 Ford government's decision to reduce the seats of the Toronto city council reminds us of the subordination of municipal governments to their respective provinces. Provinces still define municipal responsibilities, their revenues and the organization of their electoral systems. As provinces’ “creatures,” municipalities are not supposed to have direct relationships with the federal government. However, depending on government interest in cities and on conceptions of federalism, municipalities can count on some federal support. For instance, as Bradford (Reference Bradford2018) noted, the federal government tends to pursue an “implicit” national urban policy, characterized by its “informal connection, indirect leadership, and interactive governance” (15). Nevertheless, notwithstanding institutional constraints and changing relationships with the federal and provincial governments, municipalities can, in certain cases, take local action without jurisdictional authority. In fact, the absence of a definition of municipal powers in the Constitution can facilitate the inclusion of municipalities in domains that are not clearly part of their mandates (Smith and Stewart, Reference Smith, Stewart, Young and Leuprecht2006). As for FMCs, their representative organizations express various demands for greater autonomy based on their aspirations to democratic representation and political participation. They aim to gain more control over their institutions and the services they deliver (Forgues, Reference Forgues2012). To meet these claims, multiple joint-governance and consultative mechanisms have been created in order to involve FMC representative organizations in the design and the implementation of public policies. In specific areas, such as education, some researchers note that they even enjoy a limited form of nonterritorial autonomy (Chouinard, Reference Chouinard, Goodyear-Grant and Hanniman2019). The recent—albeit precarious—inclusion of some FMC representative organizations in intergovernmental debates also indicates forms of recognition of their political and democratic representation roles.Footnote 5 Yet many argue that their closer integration in the policy-making process has also resulted in a larger financial dependence on the federal government, limiting FMC autonomy, as well as the ability of FMCs to tailor activities and services (Forgues, Reference Forgues2012). FMC inclusion within governance spheres is distinct from a right to autonomy that would force the federal government to delegate a portion of its power (Léger, Reference Léger, Cardinal and Forgues2015). Even if FMC aspiration for autonomy structures with real normative power is possible, the realization of that power would still depend on the discretion of the legislator (Foucher, Reference Foucher2012). In sum, ambiguities around status and mandates create some openings, which enable municipal and civil society actors to manoeuvre in the governance of immigration and exceed their traditional policy stances in order to become vehicles for public action.

Implication of municipalities and FMCs on the immigration continuum

Municipalities and FMC organizations began designing and implementing measures and policies toward immigrants in the mid-1980s and mid-1990s, respectively. Their involvement along the continuum (from attraction/selection to citizenship) became more visible in the 2000s, corresponding to their increased participation in multilevel and collaborative governance arrangements (Fourot, Reference Fourot2015). Both entities are most active in the area of integration and the provision of services. They have developed programs, networks and partnerships to provide recreation and cultural services, support for employment and businesses, anti-discrimination programs and English/French language training.

At present, measures and programs developed by municipalities and FMC organizations in the area of immigration are closely tied to their participation in RIFs and LIPs. These networks are excellent illustrations of multilevel and collaborative governance arrangements and are made up of various stakeholders involved in immigration.Footnote 6 The RIFs were created in 2003, coming out of discussions held by the joint Citizenship and Immigration Canada–Francophone Minority Communities Steering Committee (CIC-FMC Steering Committee) in 2002.Footnote 7 This committee acknowledged francophone communities’ lack of capacity to recruit, receive and integrate French-speaking immigrants; it also confirmed the importance of acting in the interests of francophone communities when designing and implementing policies. The LIPs were created in 2008, following discussions within the Municipal Immigration Committee in Ontario (Burr, Reference Burr2011). Initially limited to this province, LIPs were extended to the rest of the country in 2012, demonstrating the federal interest in encouraging increased municipal involvement in immigration. In fact, the mere creation of the LIPs may be interpreted as an occasion for Ottawa to deploy an urban agenda on immigration without actually naming it. Indeed, the federal government finances indirect services; municipalities may, or may not, serve as LIP institutional leaders and LIP programs are conceptualized by local communities.Footnote 8 Nevertheless, this form of remote steering ensures federal government presence in key economic, social and cultural hubs—an approach that also allows the federal government to shape local activities and programs without “provoking” the provinces, which might view more direct relations with municipalities as an encroachment upon provincial jurisdiction. Municipal involvement within different LIPs is not uniform, as the model allows for varied local arrangements. Neither the LIPs nor the RIFs offer direct service delivery. They remain under the supervision of what Doberstein refers to as a “metagovernor” (2013)—namely Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) bureaucrats. Both networks remain convening and steering bodies whose main goal is to foster partnerships to better coordinate services delivered by LIP members at the local level, and, provincially, by RIF participants.

If the decision of “who gets in” remains ultimately a prerogative of the federal and provincial governments, cities and FMCs are not formally prohibited from getting more involved in immigrant selection. Therefore, in continuity with the Atlantic Pilot program, the federal government launched a Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot program in 2019 giving local stakeholders, in partnership with rural communities, the ability to recommend candidates for permanent residency. In line with these recent regionally focussed immigration initiatives, IRCC plans to launch a new Municipal Nominee program, aimed at helping small cities address their particular labour force needs. Although the details of this pilot are still to be unveiled, its main goal is to allow municipalities, chambers of commerce and local labour councils to directly sponsor their permanent residents (IRCC, 2020).

FMCs are also particularly vigilant with regard to selection tools since immigration is viewed as an instrument to preserve linguistic duality in Canada.Footnote 9 In this context, cities and FMC organizations have developed specific strategies for attracting immigrants to their communities.

Finally, cities have implemented policies aimed at counterbalancing more restrictive approaches to immigration policies and citizenship. Allowing permanent residents to vote in municipal elections is being discussed in Moncton and Winnipeg, whereas Vancouver passed such a resolution in 2018. Adopting an “access without fear policy” to provide access to municipal services regardless of immigration status is also on the agenda in Winnipeg,Footnote 10 while Vancouver adopted such a policy in 2016. Both cases show that municipalities are active in areas not traditionally assigned to them. Paradoxically, one can argue that municipalities are active in these areas because they know that franchise rights in municipal elections depend on provincial approval and that cities follow federal laws in matters of deportation. I will elaborate on this point in the next section. For FMC organizations, the launch of the Welcoming Francophone Communities—an initiative introduced by the federal Francophone Immigration Strategy and supported by the Action Plan for Official Languages 2018–2023—shows the recognition of FMC legitimacy in welcoming immigrants. The initiative can be viewed as a kind of citizenization tool—that is, the progressive building of a relationship between citizens and a political community (Auvachez, Reference Auvachez2009)—that contributes to fostering a sense of belonging (and retention rates) among French-speaking newcomers (Sidney, Reference Sidney2014).

Overall, despite the lack of formal responsibilities in immigration, the ambiguities surrounding the mandates and the roles of both municipalities and FMC organizations do not preclude their participation in the governance of immigration. On the contrary, ambiguity around their mandates and status appears to be one factor that enables their activism. Empirically, cities and communities as diverse as Moncton, Vancouver and Winnipeg are active on the immigration continuum, providing both direct and indirect services, as well as politically representing the interests of immigrants. The role of ambiguities is not limited to being a driving force of public policy, however. In the next section, I analyze how activism and collaboration in turn create new ambiguities, as well as the strategies actors adopt to manage them.

Table 2 summarizes the roles of ambiguities as conditions and outcomes of FMC and municipality participation in the governance of immigration.

Table 2 Roles of Ambiguities in the Participation of Municipalities and FMCs in the Governance of Immigration

Ambiguities as Outcomes of Collaboration

Actors participating in the governance of immigration are motivated by the prospect of contributing to the economic success of their communities, as well as to the social and cultural integration of newcomers. Collaboration is often praised, particularly when it leads to fewer gaps or overlaps in service delivery and a better coordination between actors. However, collaboration can create new ambiguities in governance processes because it often involves imbalances in power relations, leadership and authority; differences in capacity, legitimacy and resources; competition between stakeholders; and consequences in the area of advocacy and accountability.

Power relations, capacity, advocacy and competition

While promoting collaboration and a local-based definition of policy goals, FMC and municipality participation in immigration allows the federal government to gather specific information and to gain some form of indirect control over other stakeholders. Given the nature of Canadian federalism and the geographic scope of the country, the capacity of metagovernors to steer networks in specific directions is critical. Stakeholders who observe this dynamic see it as a form of asymmetrical power relations, with some even describing them as “father-child relationships”Footnote 11 between a federal government that funds services and those who deliver them.Footnote 12 In all cases, the funder's presence at the table influences the other actors’ discourses, including those of city governments who avoid controversial topics deemed “too political,”Footnote 13 and therefore tends to create forms of “advocacy chill” (Acheson and Laforest, Reference Acheson and Laforest2013).

Capacity and resources are critical factors to be considered when stakeholders are engaged in a collaborative process. The “survival mode” under which several francophone organizations describe themselves as operating limits their ability to participate in collaboration mechanisms. Instead of establishing mid- to long-term strategies, they spend their time on administrative duties or on “fighting” to keep or obtain funding.Footnote 14 This is paradoxical since one of the main goals of collaboration is to increase FMC capacities.

Therefore, collaboration can lead to an increased rivalry in the context of scarce resources for not-for-profit organizations. While promoting collaboration through RIFs and LIPs, the federal funding arrangement in fact favours competition in the settlement sector and might contribute to confusion and distrust. Because IRCC covers LIP administrative costs but does not fund implementation strategies, LIPs need to seek external funding, potentially putting the network in competition with its own members (Angeles and Shcherbya, Reference Angeles, Shcherbya, Gurstein and Hutton2019). In certain cases, both IRCC and FMCs are aware that tensions might have increased because of collaboration: “There is tension between partners . . . we know that certain RIFs face challenges regarding the roles and responsibilities of everyone involved. It's not always clear . . . there are many new actors in the field of francophone immigration.”Footnote 15 This is notably the case in the area of economic development and employability where the RIF and Réseau de développement économique et d'employabilité (RDÉE) are both active players. As one IRCC public servant highlights:

In some cases, the RIF coordinator will work very well with the RDÉE, but in other cases, there is competition between them. This leads us to reflect over whether this is indeed the best model . . . whether we are doing everything in our power to help RIFs and whether or not our work is doing more harm than good. We have to evaluate this.Footnote 16

FMC evaluation tends to concur that the government contributes to this competition because of the funding model.Footnote 17

Legitimacy and accountability

This is far from being an isolated case since IRCC is the main funding body for the RIFs and the LIPs. Beyond conflicts about funding or the legitimacy needed to offer certain services to newcomers (for example, the resettlement of Syrian refugees in New Brunswick),Footnote 18 closer collaboration between networks can trigger other concerns. For instance, is the RIFs’ absorption by the LIPs one implicit goal of the federal government? Those questions are crucial for FMCs, which, above all, seek to avoid comparison with ethnic groups or “multicultural” community organizations. As expressed by one FCFA representative:

I'll give you an example of something that completely outraged me. I yelled. . . . There's something . . . either a forum or a day of reflection that is being prepared in the West, organized by the LIP, the title being: “How do we engage francophone and ethnocultural communities?” See, there isn't even room for discussion. When you see those two words together . . . , bringing an official language community to the same level as an ethnocultural community, it's very dangerous.Footnote 19

Tensions between anglophone and francophone organizations, or between underrepresented groups—such as newcomers and Indigenous peoples—illustrate well the specific roles of race, language and national identities in Canadian political competition (Good, Reference Good2014).Footnote 20 In Winnipeg for instance, there is a competition

for resources for programming specifically for underprivileged people which both the newcomer and indigenous population fall into . . . there is a successful youth program through the Indigenous Relations Division of the City that provides internship and summer employment for Indigenous youth. And the newcomer group wanted to use that as a model for the city to create such a program for newcomer youth. And that didn't quite work yet.Footnote 21

Moreover, when actors wear multiple hats—such as networks coordinators and employees of an organization—questions are sometimes raised regarding the interests they represent. As explained by an IRCC public servant:

Ideally, the networks would be independent, but their status is not always clear as they are not incorporated. . . . They must receive funding from a recognized institution that has all the necessary paperwork. As a result, we must finance an organization to manage the RIF. However, at times the RIF coordinator will have . . . Uhm . . . an employer who has different requirements to fulfill than the members of the RIF, which often puts the coordinator in a problematic situation.Footnote 22

Finally, collaboration can create new forms of ambiguities in terms of accountability. For instance, collaboration might be use as a way to “pass the buck.” According to a community leader:

You know, the IRCC's argument that they are not alone in immigration . . . Employment and Social Development, for the credential recognition and all that . . . It remains that it's they who have the leadership . . . It's they who have the leadership. They have a responsibility to work with other partners to fairly develop a policy that holds up in terms of immigration.Footnote 23

The same applies to municipal governments and their relationships with other community stakeholders. In Moncton, for instance, the municipal government insists that it is the “individual organizations that do the actions; the LIP helps coordinate, but the individual organizations move the actions forward.”Footnote 24 In this case, who is accountable for the decisions made? Is it the agreement holder that has the partnership with the federal government or the community partners that decide on the actions to pursue? This situation is even more complicated when the agreement holder is not a governmental body (such as in the cases of RIFs and nonprofit organizations for the LIPs) and has no formal democratic legitimacy. Moreover, one characteristic of the nonprofit sector is that it has multiple forms of accountability (immigrants, communities, boards, staff, general public, and so on). How are these forms of accountability balanced, given that accountability to the funder seems to trump all of them (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Richmond and Shields2017)?

Given all the “flaws” and the complications attributed to collaborative governance, one might think that local actors do not support these types of arrangements. However, none of them have considered withdrawing from these networks, and overall, they are very supportive of them. One discourse emerging from this situation is to reduce the ambiguities resulting from collaboration, notably in clarifying stakeholders’ roles. However, as we have seen, those arrangements work precisely because they rely on a certain degree of ambiguity. Moreover, actors do not have the same capacity and resources to influence collaborative arrangements, which explains, at least in part, why actors develop strategies to manage those ambiguities rather than reject them.

Approaches to Navigating within a Collaborative and Multilevel Governance Framework

I have observed three main approaches to navigating the ambiguities created by a multilevel and collaborative governance framework. One approach consists of maintaining or even creating certain ambiguities, a second relies on exploiting them, while a third involves delegating its management to others. Those approaches are not exhaustive or mutually exclusive. Nevertheless, they illustrate three major ways in which actors manage ambiguities and give meaning to them, and in this way engage in policy making (see Table 3).

Table 3 Navigating Ambiguities in a Multilevel and Collaborative Governance Framework

Maintaining ambiguities

The first approach aims to maintain ambiguity, precisely to drive action without the “burden” of accountability. As democratically accountable bodies, governments seek credit and face potential sanctions from their electors (Weaver, Reference Weaver1986). For municipalities, this means maintaining a blurred definition of their responsibilities in immigration. For instance, Winnipeg has not yet adopted a specific immigration policy despite its inclusive political discourse (for example, the mayor's commitment to welcoming and supporting refugees) and some immigration-related activities. Rather, the city has developed a civic approach that favours the notion of “diversity” in “religions, education, sexual orientation, cultures, styles, belief systems, ways of thinking, and much more.” In this sense, the term “newcomers” does not specifically refer to an immigration status but includes all newcomers to the city. Likewise, immigration is considered through nonspecific departments (for example, Community Services) and advisory committees (for example, Citizen Equity Committee). Similarly, the city has not formally implemented measures in support of young “newcomers” despite providing internships and summer employment opportunities for Indigenous youth. The municipal justification for this approach is the presence of legal obstacles to “self-declaration” compared to employment equity groups such as “Aboriginal.”Footnote 25 Nevertheless, having a “general policy” based on an ambivalent definition of “newcomers” also prevents the municipality from shouldering responsibility in this area.Footnote 26 Indeed, one key feature of the diversity rhetoric is an ambivalence and vagueness (Schiller, Reference Schiller2017) that results in an increased level of discretion in implementation (Bastien, Reference Bastien2009), as well as in diluting accountability toward specific groups under the umbrella of advocating for inclusiveness. This approach allows the city to position itself so as to avoid blame, or to take credit, depending on the stakes at play.

Exploiting ambiguities

A second approach to dealing with ambiguities is to seek to maximize actor participation in a whole range of available mediation channels. Collaborative arrangements do not mean that stakeholders have to give up on actions they could otherwise have undertaken (such as advocacy, court challenges, political pressures or going public). On the contrary, ambiguities of means (where one might function as either—or simultaneously—partner, rival or dependent, etc.) also provide a way to access information not easily obtained. Actors can thus better negotiate for specific outcomes and/or get a better understanding about the actions of other actors in the decision-making process.

For instance, as put forward by one IRCC public servant, networks are considered “a tool through which the government and the immigration department can access information they would not be able to get otherwise.”Footnote 27 Governmental bodies are not the only ones using collaborative governance in this sense. As one francophone community representative explains, local collaboration might inform subsequent strategies at the national level: “We collect a lot of our information from the field, so as to give a better reflection at the national level. This results in . . . I don't like the term “taking a stance” but . . . having clear ideas on how to influence the strategies.”Footnote 28

Some municipal governments also embrace the ambiguities around the LIP mechanism because it is a way to counterbalance the fact that there are “no” direct relationships with the federal government. They consider it an opportunity to consolidate their position. For instance, as the LIP agreement holder, the City of Moncton saw advantages in “feeding information to the federal government” and “to be able to work more closely with it,” especially since IRCC restructured and closed several of their local offices across Canada in 2012.Footnote 29 Municipal public servants in Vancouver also consider the advantages of keeping forms of “internal advocacy”Footnote 30 with the federal government through this collaboration forum.

FMCs’ organizations play on the ambiguity of means so as to be both critics and partners of the federal government. One FCFA representative highlights the importance of maintaining a balance between pressuring and partnering with the federal government, resulting from the ambivalence around their mandates:

Part of our role is to collaborate with the IRCC-FMC committee. However, we have another mission too, that is one of representation . . . as well as advocacy . . . We have to protect our [linguistic] rights… we have to remind the federal government of its responsibilities. It is not always easy to do both. Of course. But . . . it is actually important to maintain some distance, in order to be able to intervene. . . . We work [with the federal government], but we are activists at the same time. We cannot hide from that fact.”Footnote 31

If embracing the ambiguities of collaborative governance means seeking to maximize opportunities for action and reinforcing actor capacities or power, another approach is to delegate the management of this ambiguity to others.

Delegating ambiguities

This third approach allows actors to avoid conflicts and to position themselves as leaders at the same time. The debates regarding Vancouver's status as a “sanctuary city” and the working model for the LIPs and RIFs will serve as illustrations. Federal cuts to refugee health coverage announced in 2012 triggered the opposition of frontline workers, individuals and civil society organizations, as well as governments. The City of Vancouver adopted a critical tone toward federal immigration policies, which initiated several debates within the Vancouver Mayor's Working Group on ImmigrationFootnote 32 and eventually led to the adoption of an “access without fear” policy in 2016. Nevertheless, even before the adoption of this policy, no immigration status was required to access municipal services and no immigration status information was collected by the city. In adopting this policy, the municipality recognized that the concrete impacts on its functioning were low, which can partly explain why this decision was made. At the municipal level, all the actors were aware that the main issue has always been the relationship between the police and the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA). Nevertheless, the decision-making process is worth laying bare. Doing so reveals some strategic aspects of collaborative governance, namely the self-positioning of the city as a welcoming environment, a responsive government and a progressive leader in immigration, while, in fact, it delegates the actual management of this issue to others, notably by asking the Police Board to consider adopting a similar policy. Indeed, in the two years following the adoption of the policy, the Vancouver Police DepartmentFootnote 33 (VPD) and community organizations have been in conflict over the VPD's cooperation with the CBSA. In the end, the VPD issued guidelines in 2018 to reassure victims and witnesses that contacting the municipal police would not automatically lead to their deportation but refused to dissociate itself from the CBSA and to remove their officers’ ability to contact the CBSA—an insufficient adjustment, according to some grassroots organizations.

Delegating the management of ambiguity is also an approach observed in immigration networks. The working model for the LIPs and RIFs is based on a transfer of information from the local to the federal, and vice versa. Nonetheless, because of the power imbalances discussed in the previous section, both systems mostly function as top-down mechanisms, which not only reproduce actor hierarchies in the settlement sector, due to the funding model for direct settlement services (Sadiq, Reference Sadiq2004), but also add a new tier of delegation since the federal government is the funding agency for indirect services (immigration networks) as well. In this context, not only are larger multiservice organizations (second tier) dependent on the federal government, with smaller community-based organizations (third tier) dependent on the large settlement agencies, but both of them now rely on the network coordinators and agreement holders (first tier). One federal public servant's quote illustrates the first tier of delegation: “You simply have to be able to gather key people and, for us, they [the networks] are where that work gets done at the local level.”Footnote 34 The second tier of delegation refers to the network coordinators and agreement holders who are seen as the main interlocutors of the federal government, whose particular concern is to be in relation with “one interlocutor.”Footnote 35 Finally, in the third tier, small service-provider organizations (including francophone community-based organizations within the Greater Moncton LIP for instance) are concretely doing the work of service delivery and are the most vulnerable to the delegation of ambiguity because it is difficult to move beyond the “services funder/provider relationship.”Footnote 36 In this sense, the federal government has the prerogative not to involve itself in the conflicts between local organizations—conflicts it contributes to—and delegate its management directly to them while remotely leading collaboration processes.

Conclusion

This article analyzed the implication of municipal governments and civil society actors in immigration through multilevel and collaborative governance arrangements. By shedding light on stakeholders’ agency, on institutional ambiguities and on their potential to provide critical openings for change in policy making, this research provides new theoretical insights about the factors explaining why and how actors can engage in policy-making processes, despite having no formal authority to do so. In this sense, it argues that studying the roles of ambiguities of goals and means is critical to our understanding of the activism of political entities with an ill-defined status and ill-defined mandate. This analysis is particularly resonant in Canada, extending as it does Tuohy's (Reference Tuohy1992) pioneering study of the roles played by ambiguities in the policy process. By looking at municipal governments and civil society actors, this research allows for a deeper understanding of Canadian actors’ and institutions’ capacity to innovate, experiment and mediate between conflicting interests beyond the traditional federal–provincial division of powers and without resorting to any major constitutional reforms and debates.

More precisely, this research adds to the literature on the “local turn” and to the work dealing with the rescaling of immigration governance in general by highlighting that ambiguities are both a condition—that is, a driver to activism that makes collaborative and multilevel arrangements work—and an outcome of collaboration practices. These practices are notably characterized by ambiguities regarding the actual balance of power, by collaborative aims in a very competitive sector, and by conflicting forms of accountabilities, all of which might weaken these types of governance frameworks. Nevertheless, in a context where municipalities and FMCs are in a nondominant position within the policy-making process, actors develop adaptive, rather than transformative, approaches to ambiguities.

This article also unveils three approaches that actors use in order to deal with ambiguities where resources are not equitably distributed and where the role of the federal government is critical. These approaches to ambiguities are notably a measure of that organization's own capacities and can be considered a means of reinforcing them. The first approach consists of maintaining forms of ambiguities precisely to make use of this factor, enabling activism while at the same time allowing for room to manoeuvre in a changing environment. In the second approach, actors seek to benefit from the ambiguities of collaborative governance processes to advance their own agenda and interests. Finally, the third approach refers to the capacity of stakeholders to delegate the management of ambiguities to others, while allowing actors to avoid conflicts and to position themselves as leaders in a specific domain.

Beyond the immigration sector, further research could investigate to what extent these strategies can be applied to actors involved in different sectors where networks are abundant: for example, homelessness, climate change, economic development or Indigenous affairs. In Canada, a better understanding of the role of ambiguities in public policy calls particularly for a comparison with Indigenous communities, which as we have seen, are already integrated in immigration networks in Vancouver and Winnipeg. Beyond the Canadian case, understanding the role of ambiguities could also improve our understanding of networks and their way of functioning. This is notably the case of transnational city networks (TCNs), which are at the interplay between the subnationalization and the supranationalization of policies. Indeed, TCNs (made up of network managers and city members) could be further analyzed by looking at the roles played by ambiguities as openings and opportunities for getting involved in the governance of immigration, as well as at how TCNs deal with accountability and legitimacy issues once they are mobilized in policy-making processes (Flamant et al., Reference Flamant, Fourot and Healyforthcoming).

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the three anonymous referees and to the editors at CJPS for their constructive reviews. I am also indebted to Caroline Andrew, Rachel Laforest, Rémi Léger and Christophe Traisnel for their helpful comments and important insights, which have improved the manuscript. Finally, special thanks to (former) Simon Fraser University graduate students Bella Aung and Nick Poullos for their valuable help as research assistants. This research has also benefited from Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council financial support.

Appendix