Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 November 2009

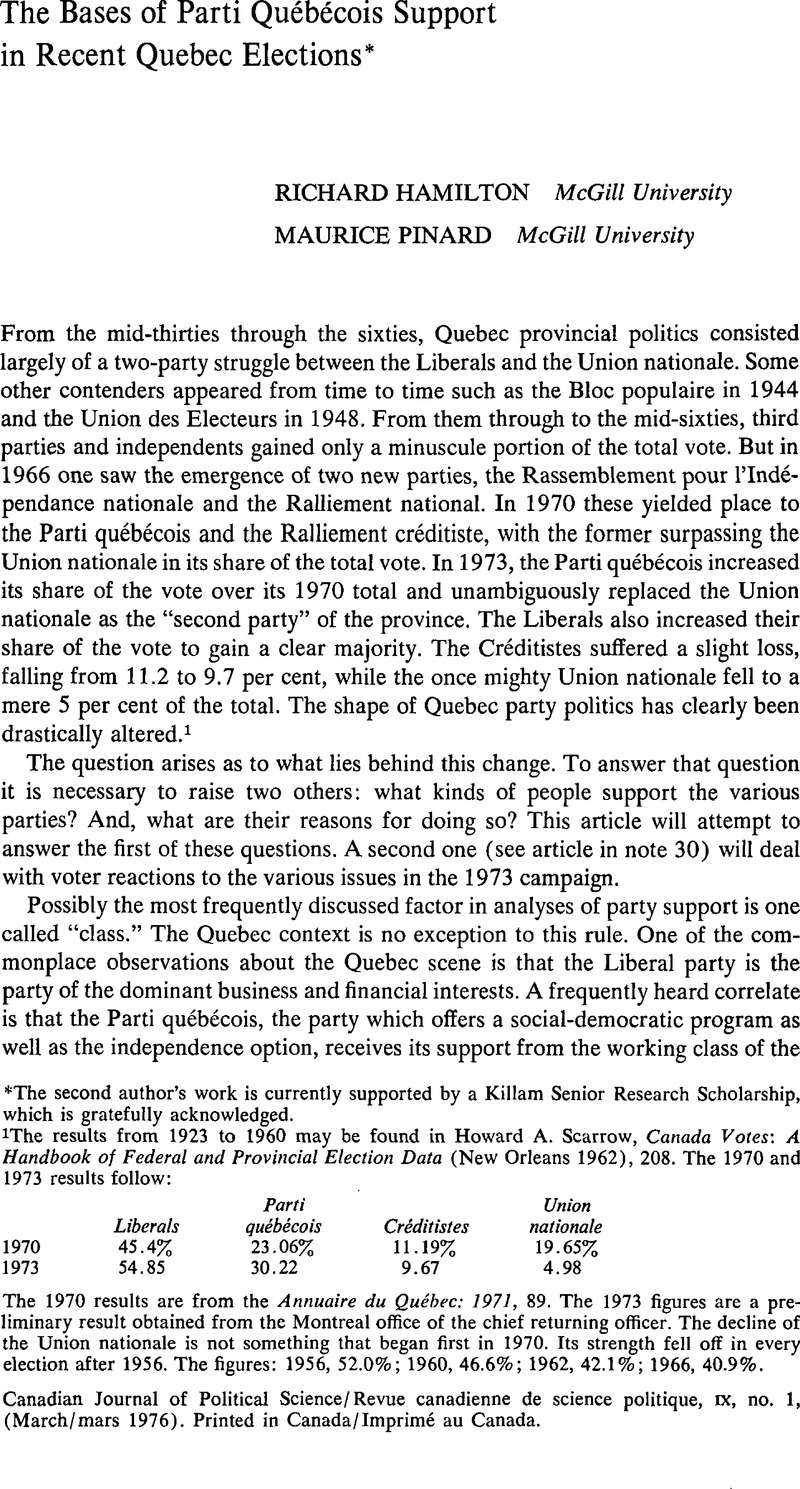

1 The results from 1923 to 1960 may be found in Scarrow, Howard A., Canada Votes: A Handbook of Federal and Provincial Election Data (New Orleans 1962), 208.Google Scholar The 1970 and 1973 results follow:

The 1970 results are from the Annuaire du Québec: 1971, 89. The 1973 figures are a preliminary result obtained from the Montreal office of the chief returning officer. The decline of the Union nationale is not something that began first in 1970. Its strength fell off in every election after 1956. The figures: 1956, 52.0%; 1960, 46.6%; 1962, 42.1%; 1966, 40.9%.

2 The best recent review of the relevant literature is that of Cuneo, Carl J. and Curtis, James E., “Quebec Separatism: An Analysis of Determinants within Social-Class Levels,” The Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 11 (February 1974), 1–29.CrossRefGoogle Scholar This article focuses, as the title indicates, on support for separatism which is not entirely the same as support for the Parti québécois. Most of the sources cited there have “tended to agree” that the “new middle class” provides the greatest support for the separatist or independentist option. Cuneo and Curtis also note that some other sources have emphasized the working-class support for separatism and for the Parti québécois. For instance Milner and Milner wrote that “in spite of the ‘bourgeoisx’ nature of its leadership, the April 1970 election revealed that popular support for the Parti Québécois came from the working class.” And “the main point… is that it was the workers that provided the mainstream of support for the left nationalist Parti Québécois”; Milner, Henry and Milner, Sheilagh Hodgins, The Decolonization of Quebec: An Analysis of Left-Wing Nationalism (Toronto 1973), 200–1.Google Scholar In addition to the work cited by Cuneo and Curtis, see Jones, Richard, Community in Crisis: French-Canadian Nationalism in Perspective (Toronto 1972).Google Scholar Discussing the 1970 provincial election, Jones reports (p. xxi) that: “No longer were the separatists a group of a few intellectuals and frustrated bourgeois. The districts supporting the Parti Québécois in Montreal were mainly lower working class areas.” Also Latouche, Daniel, “The Independent Option: Ideological and Empirical Elements,” Quebec Society and Politics: Views from the Inside, ed. Thomson, Dale C. (Toronto 1973), 119–38Google Scholar, and Drouilly, Pierre, “La brèche péquiste dans le bloc anglophone,” Le Jour, 4 mars 1974, 5.Google Scholar

3 In the United States, for example, tolerance of blacks and of ethnic minorities shows a strong inverse relationship with age. There is, accordingly, a strong positive relationship between education and tolerance. Most studies, however, have shown only small or insignificant relationships between income or occupation and tolerance. For an analysis of those relationships see Hamilton, Richard, Class and Politics in the United States (New York 1972)Google Scholar, chap. 11.

4 The Lazarsfeld-Berelson position may be found in Lazarsfeld, Paul F., Berelson, Bernard, and Gaudet, Hazel, The People's Choice (New York 1944)Google Scholar; Berelson, Bernard R., Lazarsfeld, Paul F., and McPhee, William N., Voting: A Study of Opinion Formation in a Presidential Campaign (Chicago 1954)Google Scholar; and, Katz, Elihu and Lazarsfeld, Paul F., Personal Influence: The Part Played by People in the Flow of Mass Communications (Glencoe 1955).Google Scholar This model is discussed in some detail in Hamilton, Class and Politics, chap. 2. See also Sheingold, C.A., “Social Networks and Voting: The Resurrection of a Research Agenda,” American Sociological Review, 38 (December 1973), 712–20.CrossRefGoogle Scholar The use of this position is not intended as an exclusive claim. This model is only one among many that have some validity; it proves particularly useful at this point in the analysis. Other theoretical viewpoints could also be developed, such as the impact of status as opposed to class grievances, the role of ethnic segmentation in Quebec society and the impact of contact or interdependence (or the lack there-of) on political behaviour, etc. These aspects cannot be examined with the present set of data, but will be examined in a different study.

5 The poll presented here was carried out under the direction of the authors. The interviews were done by telephone a few weeks after the election of 29 October 1973, specifically, between 22 and 26 November. The sample for the present poll was drawn and the interviews were carried out by INCI, Inc. (Information Collecting Institute, Inc. of Montreal). The sample is a systematic random sample drawn from telephone directories and is representative of all listed telephone subscribers in the province of Quebec. Of the 1500 telephone numbers chosen randomly, 1333 were retained as belonging to the sample. The 167 excluded were phone numbers of non-Canadian citizens (17), non-residential telephones (27), disconnected telephones (93), and foreign languages (30). From these 1333 members of the sample, 1012 interviews were completed. This represents a completion rate of 76 per cent. The completion rate for Montreal and the surrounding area was 74 per cent (or 442 completed inteviews from a total sample of 598). For the rest of the province, the corresponding rate is 78 per cent (570 completed interviews from a sample of 735). The uncompleted interviews (321 or 24 per cent) include: no answer after 3 or more calls, 46 or 3 per cent; individual respondent absent, 68 or 5 per cent; refusals, 195 or 15 per cent; others (sick, too old, etc.), 12 or 1 per cent.

With regard to the vote reported to have been cast in the last provincial election, our results are the following. Of the 1012 respondents, 85 per cent (or 859) reported that they had voted. Among these, 38 per cent (or 326) refused to reveal their vote; this is a high figure, but it is not out of line with the results of similar polls in the past. Moreover, it does not affect the relative strength of the parties among the remaining 529 respondents.

The second poll conducted by CROP during the 1970 electoral campaign, the one to be used here, was also based on telephone interviews. These were conducted between 12 and 19 April 1970. From the 1905 telephone numbers randomly selected, 1767 were retained as constituting the sample. From these, 1377 interviews were completed giving a completion rate of 78 per cent. For further details, see La Presse, 25 April 1970. We are very grateful to CROP and to its president, M. Yvan Corbeil, for making these data available to us for reanalysis.

The results in these two studies, taking only those expressing their party choices, are:

For the actual results see the figures in note 1.

6 These percentages were calculated from figures obtained from Elections, 1970: Rapport du Président Général des Elections (Quebec 1971). One other point may be noted about these results. Although the districts in eastern Montreal are characteristically referred to simply as “French,” there is some variation here also. The francophone percentage in Ste Marie is 92, in Ahuntsic, 83. If one assumed that very few of the “others” were voting for the Parti québécois it would mean that the level of francophone support in middle-class Ahuntsic must have been greater than in working-class Ste Marie. The author referred to in the text is Latouche, “The Independence Option.”

7 Lemieux, Vincent, Gilbert, Marcel, and Blais, André, Une élection de réalignment (Montreal 1970), 64–9.Google Scholar There are only a few studies of Quebec provincial politics in this period. They are: Jenson, Jane and Regenstreif, Peter, “Some Dimensions of Partisan Choice in Quebec,” this Journal, 2 (1970), 303–18Google Scholar; Blais, André, Gilbert, Marcel, and Lemieux, Vincent, “The Emergence of New Forces in Quebec Electoral Politics,” in Canada: A Sociological Profile, ed. Mann, W.E. (Toronto, second edition 1971), 537–44Google Scholar; Maurice Pinard, “The Ongoing Political Realignments in Quebec,” in Thomson, Quebec Society and Politics, 119–38; and Daniel Latouche, “The Independence Option,” in ibid. There are a number of analyses of polls appearing in various provincial newspapers. Of special note are those of André Blais, Vincent Lemieux, and François Renaud, “Les élections provinciales: octobre 1973” published simultaneously in Le Soleil (Quebec) and in Le Devoir (Montreal) on 20 October 1973; and a series, “L'autopsie des élections,” by Serge Carlos, Edouard Cloutier, and Daniel Latouche, which appeared in La Presse (Montréal) 19–24 November 1973. The discussion of the Lemieux et al. results in the text has omitted consideration of the lower-middle class (occupation moyenne inférieure) since that includes “artisans, commerçants et cultivateurs.” The inclusion of the farm population here makes comparison with the other categories somewhat problematic.

8 Lemieux, Gilbert, and Blais, Une élection, 62–4; Blais, Lemieux, and Renaud, Le Soleil, 21. See also Jenson and Regenstreif, “Some Dimensions of Partisan Choice,” 310. Their study, as noted, is of French-speaking voters only; it is the single exception to the first objection made in the text, but they still make no distinction of Montreal vs the rest of the province. The use of the terms anglophone and francophone in the text is not completely accurate. Our question focused on origins rather than language: “Are you French-Canadian, English-Canadian, Italian-Canadian or a Canadian of some other origin?” Use of the linguistic terms is a matter of convenience instead of the more clumsy expressions such as “those of French-Canadian origins” or those of “non-French-Canadian origins.” In our experience, it makes practically no difference in the result whether one uses a question on origins or on language.

9 Lemieux, Gilbert, and Blais, Une élection, do not report on the voting pattern by income. Latouche's study, “The Independence Option,” covers only the Montreal area, p. 184. The data from the first CROP poll of 1970 may be found.in La Presse, 18 April 1973, 7. The evidence from the second CROP poll of 1970, the one to be used here, has been recomputed by us and gives the following over-all support for the Parti québécois: less than $3000, 14%; $3000 to $6000, 23%; $6000 to $9000, 33%; more than $9000, 32%. Our study from 1973 using somewhat higher cutting lines, yielded the following over-all picture: less than $4000, 26%; $4000 to $6999, 27%: $7000 to $9999, 44%; and more than $10,000, 35%. CROP II asks about the income of the head of the household; and our study asks for total family income.

10 One can only infer this because CROP II had no occupation question.

11 Lemieux, Gilbert and Blais, Une élection, 61–2; Latouche (Montreal area only), “The Independence Option,” 184; and Blais et al., Le Soleil, 21. Jenson and Regenstreif, “Some Dimensions of Partisan Choice,” 310, have data for francophones only. The relationship by age was nowhere near as pronounced in their study (from March 1969) as in our 1973 data. Taking only those voters who indicated their party preference, our study shows anglophones to fall disproportionately into the older age categories, the respective percentages of anglophones and francophones over age 45 being 45 and 32. In part this results from high levels of non-voting among younger anglophones (see below in the text).

12 Another striking case appears in the Swedish experience. In 1960 there was a sharp inverse relationship between age and support for the ruling Social Democrats. It seemed only a question of time before they would achieve a substantial majority. Ten years later, however, there was essentially no relationship between age and support for that party (see the data below). The cohorts of 1960 appear in the adjacent column to the right in the 1970 data. That comparison, indicates that some of the young Social Democrats of 1960 had shifted elsewhere in 1970. And the youngest cohort of 1970, the latest addition to the electorate, were not following in the path of their predecessors.

Percentage supporting the Social Democrats by age

These data come from the Swedish election studies of Bo Särlvik and Olof Petersson. We wish to thank these researchers for making them available to us.

13 The failure to present results separately for anglophones and francophones is more serious with respect to education than to age since there are fair-sized differences in the educational levels of the two groups. In our study 17 per cent of the anglophone population, for example, report having 16 or more years of education as opposed to only 5 per cent among the francophones. The higher education categories, in short, are disproportionately anglophone and the latter are overwhelmingly in favour of the Liberals. It is this factor which accounts for the peculiarity noted earlier in the text, namely that the Parti québécois support increases with education except in the highest category.

14 None of the 24 francophone respondents in our study who were from farm families and who indicated their vote chose the Parti québécois. There were too few equivalent retireds to allow any meaningful comment, but see Lemieux, Gilbert, and Blais, Une élection, 64.

15 See, for example, Guindon, Hubert, “Social Unrest, Social Class, and Quebec's Bureaucratic Revolution,” Queen's Quarterly, LXXI (Summer 1964), 150–62Google Scholar; Cuneo and Curtis, “Quebec Separatism,” 2; Jones, Community in Crisis, 67; and Gilpin, Robert, “Will Canada Last?” Foreign Policy, 10 (Spring 1973), 118–31.Google Scholar

16 Blais, Lemieux, and Renaud, “les élections provinciales,” show a very similar pattern although it must be remembered that their figures include anglophones. Among professionals and semiprofessionals the Parti québécois received 53% (62)semicolon from managers, administration, and small business, 18% (56)semicolon from clerical employees, 33% (144) and from workers, 34% (125). This is based on our recalculation of their figures (so as to exclude the “don't knows” and “no answers”). Their result is based on the respondent's occupation, whereas ours are based on the occupation of the head of the family. They also report a Parti québécois percentage of 45 among students. Among francophone students the figure must be very much higher. Carlos, Cloutier, and Latouche, La Presse, fail to make any distinction within the middle class and therefore report no difference in Parti québécois support between the middle and the working classes. Latouche, does the same in his “Le Québec et l'Amérique du Nord: une comparaison à partir d'un scénario,” in Le Nationalisme québécois à la croisée des chemins (Québec 1975), 95–103.Google Scholar

17 Only a limited presentation of the evidence may be made here. Taking only those in the professional category and in the “other” middle class having 14 or more years of education, one finds 71 and 32 per cent respectively supporting the Parti québécois. The differences between the two “middle classes” are greatest among the well-educated segments. The professional category is relatively young as compared to the others in the middle class. Among those who are 34 or less, the respective percentages supporting the Parti québécois are 65 and 39.

18 Differences in typical contacts and in the language or languages used in work may be a factor. Professionals (and also service workers) are more likely to use only French in the course of their work. Administrators, office workers, and sales workers are more likely to make use of both French and English. See Carlos, Serge, L'utilisation du français dans le monde du travail du Québec, étude E 3 of La Commission d'enquête sur la situation de la langue française et sur les droits linguistiques au Québec (Québec 1973), 296.Google Scholar

19 In the Montreal area, 66 per cent (N = 38) of the workers with a family income of $7000 or more voted Parti québécois, compared to 52 per cent (N = 21) among those whose family income was less. The corresponding percentages in the rest of the province were 37 and 22 (N = 99 and 76).

20 Given the size of the sample and the necessity to control for age and residence, it is not possible to consider systematically more than one of the three basic status variables at a time. One alternative is to construct a socioeconomic status index. This we did by dividing each of the status variables in four ranks, with scores from 1 to 4. (Income: less than $4000; $4000 to $6999; $7000 to $9999; $10,000 or more. Education: less than 6 years; 6 to 9 years; 10 to 13 years; 14 or more. Occupation: semiskilled and unskilled workers; skilled workers; clerical and sales workers; professional and managerial – farmers excluded). The index scores range from 3 to 12. Dividing them into three status groups (low status, scores 3 to 6; middle status, 7 to 9; high status, 10 to 12), we obtained the following percentages voting Parti québécois within each age and residential area:

The support for the Parti québécois is always smaller among low-status than among middle-status non-farm respondents. Between the latter and high-status respondents, there are no clear patterns in the data, though the number of cases is often very small.

21 A very useful study of the development of nationalism within Quebec intellectual circles is provided by Cook, Ramsay, “French Canadian Interpretations of Canadian History,” Journal of Canadian Studies, 2 (May 1967), 3–17.CrossRefGoogle Scholar See also the studies of textbook content, notably those of Hodgetts, A.B., What Culture, What Heritage, Report of the National History Project (Toronto 1968)Google Scholar, and Trudel, Marcel and Jain, Geneviève, Canadian History Textbooks: A Comparative Study, Studies of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, Number 5 (Ottawa 1970).Google Scholar These studies are summarized in Manzer, Ronald, Canada: A Socio-Political Report (Toronto 1974), 147–50.Google Scholar

22 The Parti québécois percentages for the “core” are: Montreal area, 74% (23); other cities over 50,000, 78% (18); and places smaller than 50,000, 53% (17).

23 Some sense of the different patterns of influence within the respective settings is to be seen in response to the question on separation. Taking only those with opinions on the issue, 43 per cent of the professionals and semiprofessionals favoured that option as opposed to only 23 per cent in the “other” middle class. Those who had no opinion or were undecided about separation were asked whether they were tempted to be for or against the option. Thirty-eight per cent of the undecided professionals said they were tempted to be for separatism, not one was tempted to be against it, and the remainder were still undecided. In the “other” middle class, only 6 per cent were tempted to be for separation, 27 per cent were tempted against, and the rest were undecided. These results suggest a strong “contextual” influence.

24 Some of these members of the working-class “core” may have finished their education and may now be employed. We are not in a position to say what kind of work they are doing since we only have the occupation of the head of the households. If they do serve this “linking” role, they might constitute a weak link. If the education has outfitted them for social mobility, they might in time move away from the working-class neighbourhoods.

25 The data (blue-collar workers favouring the Parti québécois): for the Montreal metropolitan area, head of household a union member, 49% (N = 53); head not a member, 52% (N = 42); other cities over 50,000, head a member, 56% (N = 25); head not a member, 19% (N = 21); places of less than 50,000, head a member, 26% (N = 57); head not a member, 22% (N = 41). The union influence is not exclusively a blue-collar phenomenon. Taking the younger professionals, those of 35 or less, one finds all 12 of those in union families to be péquistes.

26 The respective percentages favouring the Parti québécois among the younger (to age 44) singles, marrieds, and divorced-separateds were: 58 (76); 38 (220) and 71 (14). The percentages in favour of separation were: 40 (110); 25 (305); and 53 (17). Although the number of cases is smaller, the same pattern is found among those of 45 years or more. This activist tendency on the part of the divorced and separated has been noted in other contexts as well. Heberle, Rudolf writes that in most of the cases of joiners of the National Socialist party before 1933, he found “strong indications of frustration – disappointments in their careers, conflicts or frictions in their marriage, absence of or unsatisfactory nature of sexual relations, and so forth.” From his Social Movements (New York 1951), 110.Google Scholar A study of civil rights activists in the United States found the separated, divorced, and widowed to have been the most active participants. This finding (unpublished) comes from a study by Maurice Pinard, Jerome Kirk, and Donald Von Eschen. For a study of some relevance, see their “Processes of Recruitment in the Sit-in Movement,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 33 (Fall 1969), 355–69. Another case in point is cited by S.M. Lipset who reports that in the International Ladies Garment Workers Union “studies of participants in such union organizations have revealed that they are mostly women who, for a variety of reasons, have been forced to search out formal leisure groups. These women are usually widows, divorcees, or unmarried women who have reached an age when most of their friends are married, plus another group of married women whose children have grown up.” See his Political Man (Garden City 1960), 376.

27 This point about the “mobile troops” applies only to younger single persons. Young singles are disproportionately male; older singles are disproportionately female. The former are positively disposed towards recent trade union activities; the latter are very negative. The younger singles divide fifty-fifty about the rate of change; the older singles are very much disposed to the view that change has been too fast. Young singles (those with opinions on the subject) have a majority in favour of separation. Older singles are overwhelmingly opposed.

28 One might assume that anglophones would be “conservative” in response to this question. In fact they are somewhat more positive toward the changes than the francophones. The data:

29 A similar pattern is found in the middle class although here it does not involve the same degree of contrast. Taking the three middle class groups, the Parti québécois core, the non-core péquistes, and the other middle class respondents, we havex the following percentages describing the changes as being too slow: 35, 30 and 6. The middle-class core group do not appear to be as “advanced” as the working-class equivalent. The “other” middle-class group on the other hand is more accepting of the changes than the “other” workers.

30 This is possibly the highest level of support ever given to the Liberals by the anglophones. See Pinard, Maurice and Hamilton, Richard, “Separatism and the Polarization of the Quebec Electorate: the 1973 Provincial Election,” a paper read at the Canadian Sociology and Anthropology Association meeting, Toronto, August 1974.Google Scholar