Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 January 2020

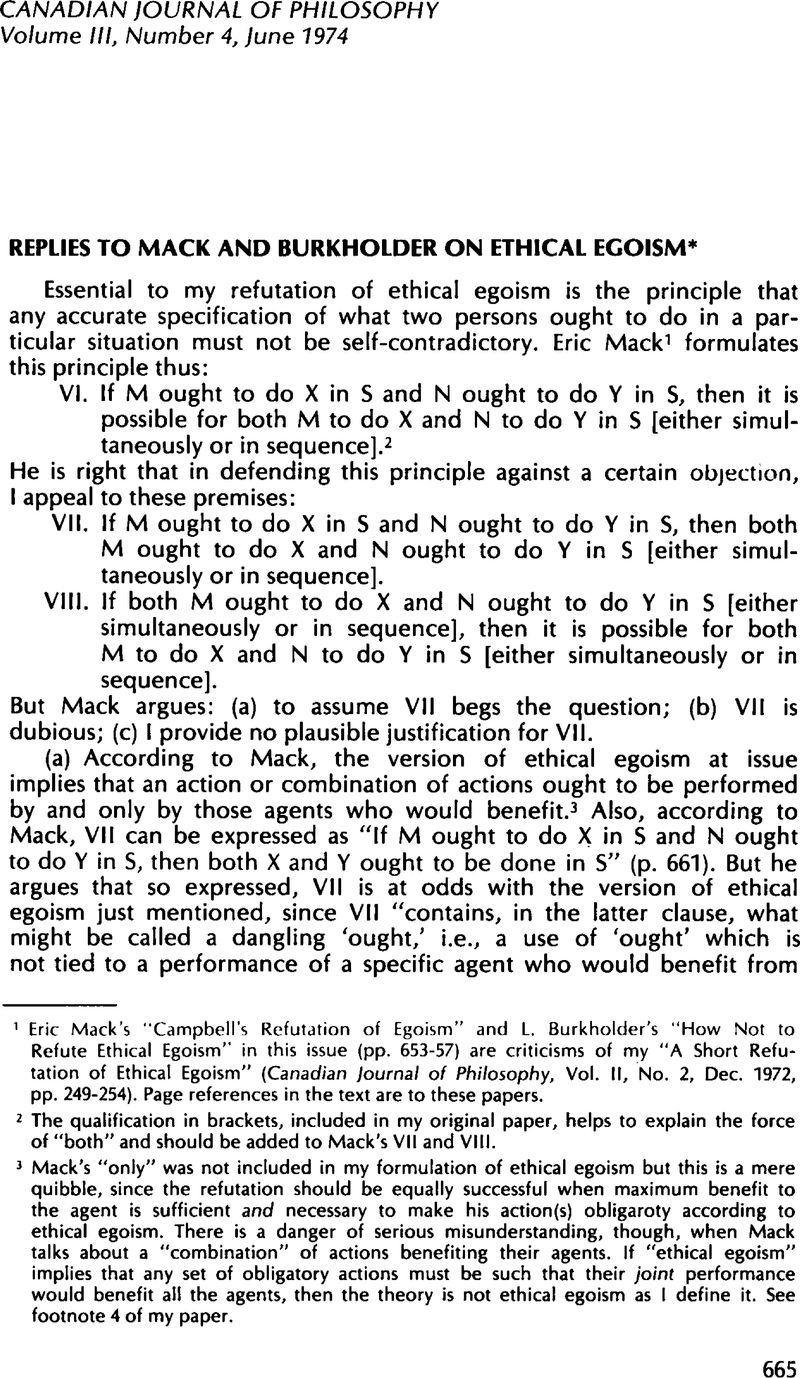

1 Eric Mack's “Campbell's Refutation of Egoism” and L. Burkholder's “How Not to Refute Ethical Egoism” in this issue (pp. 653–57) are criticisms of my “A Short Refutation of Ethical Egoism” (Canadian journal of Philosophy, Vol. II, No. 2, Dec. 1972, pp. 249–254). Page references in the text are to these papers.

2 The qualification in brackets, included in my original paper, helps to explain the force of “both” and should be added to Mack's VII and VIII.

3 Mack's “only” was not included in my formulation of ethical egoism but this is a mere quibble, since the refutation should be equally successful when maximum benefit to the agent is sufficient and necessary to make his action(s) obligaroty according to ethical egoism. There is a danger of serious misunderstanding, though, when Mack talks about a “combination” of actions benefiting their agents. If “ethical egoism” implies that any set of obligatory actions must be such that their joint performance would benefit all the agents, then the theory is not ethical egoism as I define it. See footnote 4 of my paper.

4 The notion of prima facie obligation is explained in Brandt, Richard Ethical Theory (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1959), pp. 367–8.Google Scholar

5 Sometimes principles about what ought to be done are designed to help one decide, e.g., (a) whether some person(s) would deserve blame for not doing something or (b) whether it would be a good thing if something were done. Then “ought” does not imply “can.” (a) One can reasonably be blamed for not doing what one knows one ought to do when knowing this, one has deliberately made it impossible to do that thing; and (b) one can reasonably regret that it is impossible to do certain things. Such examples lead Stocker, Michael to conclude that “ought” does not imply “can” in his important paper “ ‘Ought’ and ‘Can’” (Australasian journal of Philosophy, Vol. 49, No.3, Dec. 1971, pp. 303–316)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

6 Although I shall not attempt to analyze the meaning of “possible” or “can” in this context, a satisfactory analysis should guarantee this much: For actions to be collectively possible the assertion that all of them can be done must be logically consistent under any’ accurate description of them. Thus if two actions are collectively possible, neither can causally prevent the other. For it would be inconsistent to assert that X, which would cause Y not to be done, and also Y both can be done.

7 If this modal fallacy were not a fallacy, we would have, by substituting “not p” for “q,” a simple argument for fatalism, concluding that what ever is not, cannot be and hence that whatever is, must be. Burkholder seems to require a collapse of the distributive- collective distinction (tantamount to the “entailment” noted in the next sentence) which gives exactly this result.

8 This appellation I owe to Charles M. Young.